Difference between revisions of "Relief Work"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

AlfRedekopp (talk | contribs) ("Indian raids" replaces with "raids by Indigenous people") |

SamSteiner (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "[[Lancaster Mennonite Conference (Mennonite Church USA)" to "[[LMC: a Fellowship of Anabaptist Churches") |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

The new settlements of Mennonites in America continued the tradition of helping the needy. As early as 1756 the Franconia Mennonites in Eastern Pennsylvania organized a small relief program for the help of the Moravian communities of Northampton County who had suffered loss of life and property because of raids by Indigenous people. In 1775, when the war spirit of the revolutionary era was running high, the Mennonites joined the Dunkers in a petition to the [[Pennsylvania (USA)|Pennsylvania]] Assembly declaring it according to their principles "to feed the hungry and give the thirsty drink; we have dedicated ourselves to serve all men in everything that can be helpful to the preservation of men's lives, but we find no freedom in giving, or doing, or assisting in anything by which men's lives are destroyed or hurt." During the war the Mennonites used the facilities of the Brethren Cloister at Ephrata for hospital purposes. A Mennonite minister, John Baer, and his wife died, evidently of a contagious disease, while ministering to sick soldiers at this place. One writer says: "we may be sure from what we know of their character and customs, that many a weary straggler, invalid soldier, or destitute refugee received aid and comfort from the rich farms and hearths of the Pennsylvania pacifists." Even British fugitives received such aid. In 1783 some British soldiers who had been imprisoned in Lancaster escaped and called at Mennonite homes northeast of the city, where they received help. Local officials regarded this as an act of treason and insisted that the Mennonites be punished. Only through an appeal to George Washington himself were these Mennonites saved from a prison sentence. But they had to pay a fine. | The new settlements of Mennonites in America continued the tradition of helping the needy. As early as 1756 the Franconia Mennonites in Eastern Pennsylvania organized a small relief program for the help of the Moravian communities of Northampton County who had suffered loss of life and property because of raids by Indigenous people. In 1775, when the war spirit of the revolutionary era was running high, the Mennonites joined the Dunkers in a petition to the [[Pennsylvania (USA)|Pennsylvania]] Assembly declaring it according to their principles "to feed the hungry and give the thirsty drink; we have dedicated ourselves to serve all men in everything that can be helpful to the preservation of men's lives, but we find no freedom in giving, or doing, or assisting in anything by which men's lives are destroyed or hurt." During the war the Mennonites used the facilities of the Brethren Cloister at Ephrata for hospital purposes. A Mennonite minister, John Baer, and his wife died, evidently of a contagious disease, while ministering to sick soldiers at this place. One writer says: "we may be sure from what we know of their character and customs, that many a weary straggler, invalid soldier, or destitute refugee received aid and comfort from the rich farms and hearths of the Pennsylvania pacifists." Even British fugitives received such aid. In 1783 some British soldiers who had been imprisoned in Lancaster escaped and called at Mennonite homes northeast of the city, where they received help. Local officials regarded this as an act of treason and insisted that the Mennonites be punished. Only through an appeal to George Washington himself were these Mennonites saved from a prison sentence. But they had to pay a fine. | ||

| − | The immigration of 18,000 European Mennonites, chiefly from [[Russia|Russia]], in the decade following 1873, was the occasion for a large-scale relief and aid program on the part of the Mennonites of [[Canada|Canada]] and the [[United States of America|United States]]. Three committees were organized for carrying on this work. The first was the [[Mennonite Board of Guardians|Mennonite Board of Guardians]], organized in 1873 with [[Krehbiel, Christian (1832-1909)|Christian Krehbiel]] and [[Goerz, David (1849-1914)|David Goerz]] of Summerfield, Illinois as president and secretary, and [[Funk, John Fretz (1835-1930)|John F. Funk]] of [[Elkhart (Indiana, USA)|Elkhart]], Indiana as treasurer. The second committee known as the Mennonite Executive Aid Committee was organized in Eastern [[Pennsylvania (USA)|Pennsylvania]] under the leadership of Preacher [[Herr, Amos (1816-1897)|Amos Herr]] of the [[ | + | The immigration of 18,000 European Mennonites, chiefly from [[Russia|Russia]], in the decade following 1873, was the occasion for a large-scale relief and aid program on the part of the Mennonites of [[Canada|Canada]] and the [[United States of America|United States]]. Three committees were organized for carrying on this work. The first was the [[Mennonite Board of Guardians|Mennonite Board of Guardians]], organized in 1873 with [[Krehbiel, Christian (1832-1909)|Christian Krehbiel]] and [[Goerz, David (1849-1914)|David Goerz]] of Summerfield, Illinois as president and secretary, and [[Funk, John Fretz (1835-1930)|John F. Funk]] of [[Elkhart (Indiana, USA)|Elkhart]], Indiana as treasurer. The second committee known as the Mennonite Executive Aid Committee was organized in Eastern [[Pennsylvania (USA)|Pennsylvania]] under the leadership of Preacher [[Herr, Amos (1816-1897)|Amos Herr]] of the [[LMC: a Fellowship of Anabaptist Churches|Lancaster Conference]]. The third committee was formed by the Ontario Mennonites and was known as the Canadian Aid Committee, with [[Shantz, Jacob Yost (1822-1909)|Jacob Y. Shantz]] of Berlin (now [[Kitchener-Waterloo (Ontario, Canada)|Kitchener]]) as president. These three committees cooperated very closely and did a remarkable piece of work. They distributed literature throughout the Mennonite communities of south Russia, giving detailed instructions as to procedures for taking advantage of the provisions being made by the American committees. They had representatives in Hamburg and New York who met the immigrants and helped them with the details of their travel and transportation arrangements. They helped them make contact with the proper railway companies and arranged for very cheap immigrant fares, and gave assistance in the location and purchase of lands on which to settle. It is estimated that the assistance in money and services given by the Mennonites in the United States to the Russian immigrants amounted to more than $100,000. The [[Ontario (Canada)|Ontario]] Mennonites secured a loan of $88,000 from the Canadian government to assist the immigrants who came to Canada. In addition, private loans and gifts brought the aid given by the Canadian Mennonites also considerably above $100,000. |

=== India === | === India === | ||

Latest revision as of 19:23, 8 August 2023

1956 Article

Early History

The Anabaptist emphasis on discipleship and brotherhood required the material possessions of the Christian to be brought under the lordship of Christ. The extremes of luxury and poverty were to be avoided. Material aid and generous sharing and co-operation in economic matters were to be freely practiced, and after the manner of the Good Samaritan the needy were to be helped. Hans Leopold, a Swiss Brethren martyr of 1528, said of his brethren: "If they know of anyone who is in need, whether or not he is a member of their church, they believe it their duty, out of love to God, to render help and aid." Menno Simons, in an enumeration of qualities of the saints, says: "They show mercy and love. . . . They entertain those in distress. They take the stranger into their houses. They comfort the afflicted; clothe the naked; feed the hungry." Both the Dordrecht and the Ris confessions of faith in their statements on nonresistance emphasize the duty of the Christian to feed, clothe, and help his needy fellow men.

Anabaptist-Mennonite history is filled with illustrations of this brotherhood and "Good Samaritan" faith in action. In 1553 occurred the well-known incident in which the followers of Menno Simons at Wismar in North Germany gave asylum to a group of English Calvinist refugees who had been driven from home by the Catholic queen and then were refused admission to his country by the Lutheran king of Denmark. The Hutterite chronicles of the 17th century record the presence in their communities of numerous strangers receiving bread and alms during a time of famine.

During the 17th and 18th centuries the Dutch Mennonites gave much material assistance to their persecuted and needy brethren in Switzerland, the Palatinate, Danzig, Poland, and Moravia. In 1666 the Amsterdam city authorities, in a formal protest made to the Swiss government at the request of the Dutch Mennonites against the persecution of the Mennonites, included the following sentence: "The Mennonites are a people which at no opportunity have failed to extend noteworthy charity toward the people of the Reformed faith. Only recently, when our brethren, the Waldenses, were so cruelly driven from their homes [by the duke of Savoy], they have in this city, simply upon our recommendation, contributed the sum of about 7,000 pounds in Holland money, for the support of the aforesaid Waldenses." Following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 the Dutch Mennonites contributed similar assistance to the French Huguenots.

In 1710 the Dutch Mennonites organized the Foundation for Foreign Relief (Fonds voor Buitenlandsche Nooden), which carried on an active relief program for half a century and which was not finally liquidated until 1803. In 1711 this organization assisted 400 refugees from Switzerland to settle in the Netherlands. Other settlers followed in 1713 and subsequently. During the 1720s and 1730s large sums were contributed by the Dutch organization for the assistance of Mennonites migrating from the Palatinate to Pennsylvania. It is estimated that in 1709 the Dutch Mennonites contributed more than 270,000 guilders for foreign relief work, for the aid of both those who were going to America and those who settled in Holland. When the Mennonite World Relief Conference was held in Danzig in 1930 G. Fast in an address enumerated a long list of cases, first in which the West Prussian Mennonites had been assisted by the Dutch, and then in which the Prussian Mennonites gave aid to their brethren in West Germany and in Russia.

North America

The new settlements of Mennonites in America continued the tradition of helping the needy. As early as 1756 the Franconia Mennonites in Eastern Pennsylvania organized a small relief program for the help of the Moravian communities of Northampton County who had suffered loss of life and property because of raids by Indigenous people. In 1775, when the war spirit of the revolutionary era was running high, the Mennonites joined the Dunkers in a petition to the Pennsylvania Assembly declaring it according to their principles "to feed the hungry and give the thirsty drink; we have dedicated ourselves to serve all men in everything that can be helpful to the preservation of men's lives, but we find no freedom in giving, or doing, or assisting in anything by which men's lives are destroyed or hurt." During the war the Mennonites used the facilities of the Brethren Cloister at Ephrata for hospital purposes. A Mennonite minister, John Baer, and his wife died, evidently of a contagious disease, while ministering to sick soldiers at this place. One writer says: "we may be sure from what we know of their character and customs, that many a weary straggler, invalid soldier, or destitute refugee received aid and comfort from the rich farms and hearths of the Pennsylvania pacifists." Even British fugitives received such aid. In 1783 some British soldiers who had been imprisoned in Lancaster escaped and called at Mennonite homes northeast of the city, where they received help. Local officials regarded this as an act of treason and insisted that the Mennonites be punished. Only through an appeal to George Washington himself were these Mennonites saved from a prison sentence. But they had to pay a fine.

The immigration of 18,000 European Mennonites, chiefly from Russia, in the decade following 1873, was the occasion for a large-scale relief and aid program on the part of the Mennonites of Canada and the United States. Three committees were organized for carrying on this work. The first was the Mennonite Board of Guardians, organized in 1873 with Christian Krehbiel and David Goerz of Summerfield, Illinois as president and secretary, and John F. Funk of Elkhart, Indiana as treasurer. The second committee known as the Mennonite Executive Aid Committee was organized in Eastern Pennsylvania under the leadership of Preacher Amos Herr of the Lancaster Conference. The third committee was formed by the Ontario Mennonites and was known as the Canadian Aid Committee, with Jacob Y. Shantz of Berlin (now Kitchener) as president. These three committees cooperated very closely and did a remarkable piece of work. They distributed literature throughout the Mennonite communities of south Russia, giving detailed instructions as to procedures for taking advantage of the provisions being made by the American committees. They had representatives in Hamburg and New York who met the immigrants and helped them with the details of their travel and transportation arrangements. They helped them make contact with the proper railway companies and arranged for very cheap immigrant fares, and gave assistance in the location and purchase of lands on which to settle. It is estimated that the assistance in money and services given by the Mennonites in the United States to the Russian immigrants amounted to more than $100,000. The Ontario Mennonites secured a loan of $88,000 from the Canadian government to assist the immigrants who came to Canada. In addition, private loans and gifts brought the aid given by the Canadian Mennonites also considerably above $100,000.

India

The next important relief project of the American Mennonites was in response to the India famine of 1896-97. In 1897 the Home and Foreign Relief Commission (HFRC) was organized at Elkhart, Indiana under Mennonite Church auspices and for a decade contributed grain for famine relief aid funds for the support of orphans. The HFRC came to an end in 1906. The Emergency Relief Commission of the General Conference Mennonite Church, organized in 1899, carried on a similar work in India. This board continued in existence until it was merged with the Board of Christian Service in 1950. It served as a relief agency to aid members in needy North American congregations after the work in India was completed. An important outcome of these projects was the founding of two India Mennonite missions, the Mennonite Church in 1899 and the General Conference Mennonite Church in 1900. The Mennonite Brethren in Christ Church in 1898 started orphanage work at Hadjin, Turkey, for Armenian survivors of the Turkish massacres.

Post World War I Europe

The Mennonite (MC) Relief Commission for War Suffers (MRCWS), organized in 1917 at Elkhart, was the official agency through which the Mennonite Church (MC) supported the Friends reconstruction work in France and other European Relief projects as well as the Near East relief following World War I.

In 1919 the MRCWS appointed a committee of three reconstruction workers then serving in France, A. J. Miller, J. Roy Allgyer, and A. E. Hiebert, to investigate opportunities for relief work in other parts of Europe. Leaving Paris on 9 October 1919, they spent three and one-half days in Berlin, traveled through Leipzig, Dresden, and Prague, and spent five and one-half days in Vienna; then continued through Budapest and Bucharest and spent six days in Odessa and Kherson, South Russia. They visited hospitals, welfare centers, and charitable institutions, and reported great shortages of food, clothing, and fuel, accompanied by suffering, want, and disorganization wherever they went; the opportunities for a Mennonite relief work were great, working either independently or in co-operation with the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC). In the meantime, however, the MRCWS had committed itself to the Near East work, its first workers having sailed in January 1919. Hence no extensive work was undertaken in any of the countries visited by the above team except Russia.

In 1920, however, John J. Fisher was stationed in Vienna, where he engaged in child feeding work under the Quaker organization. Russell Lantz transferred from the French Reconstruction Unit to Poland, where he worked under the Quaker relief organization. Four workers transferred from France to Germany; Atlee Hostetler, Homer Hostetler, and Ora R. Liechty assisted in chief feeding work under the AFSC, and Solomon E. Yoder visited families of German prisoners of war who had worked for the AFSC reconstruction unit in France, and remunerated them for their service. Russell Lantz worked for a time in Poland under the AFSC. The AFSC administered the entire German section of the European Children's Fund program which began in February 1920. At one time this organization was feeding 1,000,000 German children daily. The AFSC asked S. E. Allgyer to organize support for this program among all branches of American Mennonites. This offer was not accepted, however, because of commitments by the MRCWS in the Near East and Russia.

The American Mennonites did, however, give considerable support to the South German Mennonite relief organization, Christenpflicht, founded in 1920 under the leadership of Michael Horsch. In 1922 Horsch visited the American Mennonites in behalf of this work and in 1930 he reported that during this period the total receipts of Christenpflicht had been about $62,000, of which $44,000 had been contributed by the MRCWS, $8,500 by the Emergency Relief Commission (GCM), $6,500 by other American Mennonite sources, and the remainder by the European Mennonites. Closely associated with Christenpflicht was the Mennonitische Flüchtlingsfürsorge, later called Deutsche Mennoniten-Hilfe, also organized in 1920, with headquarters at first at Heilbronn, for the assistance of Mennonite refugees from Russia. This organization operated a refugee camp at Lechfeld.

Near East Relief (NER)

Another needy relief field was the Near East. For many years the Armenians and other Christians had been persecuted by the Turks. Perhaps a million had been killed or died as a result of mistreatment. Perhaps another three quarter million lived as refugees and orphans in various parts of the old Turkish Empire. In addition to the obvious need of the sufferers, this field of service appealed to the American Mennonites because its location was in Bible lands which it was believed would provide opportunities for a new mission field.

As early as November 1915 the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, later known as the Near East Relief, was organized. The NER was able to do a small amount of work during the war. As soon as the war was over, however, it was ready to operate on a large scale, using missions and mission schools throughout the region as the base of operations. A plan was launched to raise $30,000,000 during the winter of 1918-19. The cause was promoted through American Sunday schools, who were asked to raise $2,000,000. The General Sunday School Committee of the Mennonite Church (MC) cooperated in this plan.

Scan courtesy Mennonite Church USA Archives-Goshen Photograph Collection binders. Photo #1704

On 4 January 1919, the MRCWS accepted an invitation from the NER to cooperate in its work by contributing personnel and funds. Five days later payment of $20,000 as the first financial contribution to the NER was authorized. On 25 January 1919, the Pensacola sailed for Beirut carrying 42 relief workers and 5,000 tons of relief supplies. Among the relief workers were nine Mennonites, seven young men going out as workers under the direction of Aaron Loucks and William A. Derstine, the latter two men having the responsibility to locate and organize a field of work and to determine its relation to the Near East Relief. It was hoped that a semi-autonomous work could be organized under the general administration of the NER, conversations with the NER headquarters in New York apparently having suggested this possibility. It was also hoped that the Mennonite relief program in the Near East would lead directly to the establishment of mission work. After further study, however, the idea of a semi-autonomous Mennonite unit was abandoned. Loucks and Derstine then sailed for home, while the seven young men remained in Beirut in the service of the Syrian area of the NER under the direction of James H. Nicol.

The reasons for abandoning the original plan for a Mennonite relief unit were (1) the inexperience of the Mennonite Church; (2) confusion within the administration of the NER, particularly lack of understanding between its New York office and its Constantinople director; (3) the poor prospects for a mission in the area since the field was covered by other long-established missions; (4) the need for the services of the Mennonite workers within the NER organization at Beirut.

Of the seven men in the first contingent Orie O. Miller became administrative assistant to Nicol and assistant director of the Syrian area extending from Port Said to Mardin, in which at least 7,000 orphans were located; David Zimmerman was construction engineer; Ezra Deter was engaged in transport in the Beirut district; William Stoltzfus and Silas Hertzler had charge of orphanage work in Sidon; B. F. Stoltzfus was assistant director of an orphanage in Jerusalem; and C. L. Graber was director of a refugee camp and industrial work in Aleppo. During 1919 nine more Mennonites entered the NER service and in the next two years 13 more men and two women did so, making a total of 31 Mennonite NER workers. The work of these men and women was similar to that of the original seven. One of the men, Menno Shellenberger of Kansas, who sailed with the last group in July 1921, died on the field. The total financial contribution of the American Mennonites to NER was $339,000, of which $326,000 was contributed through the Mennonite Relief Commission for War Sufferers (MC) and the Eastern Mennonite Board of Missions and Charities. While the original hopes for the establishment of a semi-autonomous or even an independent Mennonite relief project in the Near East were not realized, the workers on the field and the American Mennonites as a whole gained much valuable experience through their co-operation with NER, as well as earlier with the AFSC in the French reconstruction work.

Russian Relief Request

As early as 1919 M. B. Fast, W. P. Neufeld, and B. B. Reimer, Mennonites of Reedley, California, collected funds, clothing, and relief supplies amounting to more than $40,000 for the suffering Mennonite communities in Siberia, which were at that time not under Soviet rule. Fast accompanied the shipment in person and was joined later by Neufeld. Following their return the Emergency Relief Committee of the Mennonites of North America was organized 4 January 1920, at Hillsboro, Kansas, with P. C. Hiebert as chairman and M. B. Fast as general secretary; but it soon found the door to Siberia closed by military developments.

In June 1920, however, the Studienkommission, composed of four Mennonite delegates from Russia, came to America to solicit help for their people who were suffering from famine, many of whom desired to emigrate. In response to this need and appeal the MCC was organized in July 1920 for the operation of a joint Mennonite relief program. The Emergency Relief Committee of the Mennonites of North America now joined its forces with the new movements as did the MRCWS, the Emergency Relief Committee of the General Conference Mennonite Church, the Eastern Mennonite Board of Missions and Charities, the Krimmer Mennonite Brethren, and the Mennonite Brethren Church. P. C. Hiebert was elected as chairman (serving until 1952) and Levi Mumaw as executive secretary (serving until his death in 1935), after which Orie O. Miller was chosen to fill his place (serving until 1958).

The Constantinople Unit

In August 1920, a church-wide program was launched for the gathering of new and used clothing, and in September twenty-five tons of clothing were shipped and three men sailed from New York to open the work in Russia, these being Orie O. Miller, Arthur W. Slagel, and Clayton Kratz. They reached Constantinople on 27 September and found numerous refugees from Russia, including some Mennonites, in the city. Slagel then remained in Constantinople with the shipment of goods and acquainted himself with the work of the NER, while Miller and Kratz went to Sebastopol, arriving on 6 October 1920, from whence they pushed up into the Mennonite territory to survey the needs and complete plans for carrying on the work. After spending a few days there Miller returned to Constantinople to bring in the supplies in company with Slagel, while Kratz remained in Russia.

Although the Soviet government was now about three years old, the opposition forces had not been completely subdued, and at the time when Miller and Kratz came into Russia the White army of General Wrangel was in control of much of the area of the Mennonite settlements. Before Miller returned from Constantinople, however, Wrangel's forces were defeated and Clayton Kratz was caught behind the Bolshevik lines. He was later taken into custody by Bolshevik authorities and has never been heard from since. It is assumed that he died at their hands. Another result of Wrangel's defeat was the flight of about 130,000 refugees, including 200 Mennonites, from Russia to Constantinople. When they arrived many of them were unable to leave their ships for almost a month. The condition of these people was so appalling that the MCC found its first task to be that of helping to care for them. An orphanage was opened for the care of the children, and a department was opened for the distribution of the clothing which had been sent over. A home was opened for women and girls, and also a Mennonite home to care for the Mennonites on the refugee ship. Besides these four projects the MCC had charge of four smaller camps outside the city where they distributed soap, fuel, clothing, medicine, and other necessaries. This work in Constantinople was finally closed in July 1922. The total amount expended for the work of the Constantinople unit was over $200,000. Of this amount more than $14,000 was used to assist a group of sixty-four Russian Mennonite refugees to come from Constantinople to America. In addition to Arthur W. Slagel, the workers comprising the Constantinople unit were B. F. Stoltzfus, J. E. Brunk, Vesta Zook, and Vinora Weaver.

Relief Work in Russia

Early in 1921 Alvin J. Miller, who had been with the reconstruction service in France, was appointed by the MCC as director of relief work in Russia, which was now almost completely under Soviet control. He came to Constantinople on 29 January 1921, and then early in April, in company with Arthur W. Slagel, he sailed for the port of Novorossisk on the Black Sea, but they were refused entry into Russia. Miller now turned to Western Europe to make contact with Soviet diplomatic missions there, particularly in London. The Soviet government was very suspicious of all outside influences; therefore Miller's task was a very difficult one. But after making many contacts with the Red Cross, with Herbert Hoover's American Relief Administration, with the Quaker organization, and other agencies, Miller finally found his way to Moscow and gained an audience with the head of the Russian Central Commission for Combating Famine, who signed an agreement on 1 October 1921, stating the terms whereby the MCC would be permitted to carry on relief work in South Russia. Although the American Relief Administration had received permission in August 1921 to open work in Russia, authorization to do so in the Ukraine was not granted until January 1922, three months after the MCC agreement was signed.

The MCC operated in that part of Russia where the Mennonites lived, but relief was given to the entire population regardless of race or creed. Extensive work was carried on in some villages where no Mennonites lived at all. The method of work was to establish feeding kitchens in villages and distribute food to the needy. By May 1922 the Mennonites were feeding 25,000 persons daily, and by August the figure had reached 40,000. The feeding kitchens continued in operation through the summer of 1924. In addition to this service the MCC distributed food packets sent by Americans directly to their relatives and friends in Russia. Fifty or more Fordson tractor plow outfits were also shipped to the Mennonite villages by the MCC, these to take the place of the horses lost to the villages during the time of the war. The American Mennonites spent a total of about $1,200,000 for the relief work in Russia, and this was supplemented by several hundred thousand dollars contributed by the Mennonites of Holland, who also sent two Dutch representatives to the field in Russia. The total amount contributed by the American Mennonites and distributed through its own organizations for the relief of war sufferers in Europe and the Near East during World War I and immediately afterwards is estimated at about $2,500,000. In addition to O. O. Miller, A. J. Miller, and Clayton Kratz, the Mennonite relief workers in Russia included G. G. Hiebert, P. C. Hiebert, D. R. Hoeppner, Barbara Hofer, D. M. Hofer, C. E. Krehbiel, Daniel Schroeder, A. W. Slagel, P. H. Unruh, and H. C. Yoder. In August and September 1921, Jacob Koekebakker, pastor of Middelburg, as a representative of the Dutch Mennonite Committee for Foreign Needs, negotiated with the authorities at Moscow, where he worked with Orie O. Miller. Pastor F. C. Fleischer had charge of the food and clothing shipments of the Dutch Mennonites in the Ukraine from early 1922 until the summer of 1923. R. J. C. Willink was the director of the Dutch relief action in Russia.

Emigration from Russia

Besides its relief program in Russia, MCC had an important part in the migration, although at first several other Mennonite organizations were effected to carry on this task. One of these was the Mennonite Board of Colonization organized in 1920 at Newton; the other, the more important one of the two, was the Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization with headquarters at Rosthern, Saskatchewan, organized in 1922 under the leadership of David Toews. The Canadian Pacific Railway and Steamship Company welcomed the prospect of new immigrants to settle the lands in western Canada, especially since it had confidence in the Mennonites because of the splendid record of the immigrants of the 1870s in repaying the loan which they had received from the government.

In the summer of 1923, therefore, the railway company readily entered into an agreement with the Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization to transport 3,000 Mennonites from Russia to Canada at the rate of $140 per person on a credit basis. To this was to be added the railway fare from the port of entry to their final destination. The credit was extended without collateral, the Board of Colonization, with no assets, alone being liable for payment; individual members of the board assumed no financial responsibility. When the first 3,000 immigrants had arrived the contract was renewed. Renewal was repeated from time to time until by 1927 about 20,000 Russian Mennonites had arrived in Canada. The railway and steamship company extended a total credit of $2,000,000. In spite of the long depression years about two thirds of this amount had been repaid as early as 1940, and by 1945 the entire debt had been liquidated. In 1925-26 about 600 immigrants were brought from Russia to Mexico with the aid of the Mennonite Board of Colonization of Newton. Later, however, most of these removed to the United States or Canada. The few who remain live in a little settlement of their own at Cuauhtemoc, near the larger colony of Mennonites from Canada.

During the years following the Russian revolution, while some of the Mennonites were finding their way from Russia to America, many others were trying to restore the life of their old communities, hoping that the Soviet government would develop a policy of tolerance making it possible for Mennonite life to continue in a normal way. During the period of the New Economic Policy, 1921-28, it seemed as if this hope might eventually be realized; but after Stalin introduced his Five Year Plan in 1928 for the complete communization of Russia this hope was brought to an end. Those Mennonites who had the courage to maintain their individuality and their religious life soon found their property confiscated and sold, and themselves deported to northern Russia, where they suffered untold hardships and perished in large numbers. By 1929 the situation was so desperate that thousands of them determined to leave the country at any cost.

In the late spring of 1929 a few families from Siberia went to Moscow to secure passports for emigration. Finally, in August permission was granted them to leave. As soon as the news reached the Mennonite settlements there was a literal march on Moscow to secure passports. In a short time 15,000 would-be emigrants, chiefly Mennonites, were in the city, and it was estimated that 40,000 more were on the way. "It was a mass movement, unplanned, unorganized, hysterical almost." The government refused to grant passports, however, and made desperate efforts to stop the movement. Police were sent to the colonies to prevent Mennonites from boarding the trains and leaders were imprisoned. Thousands of the would-be emigrants encamped about Moscow were arrested and shipped, in unheated, sealed stock cars, to South Russia or Siberia in the cold of November and December.

Of this large number who sought to emigrate 6,000, two thirds of whom were Mennonites, however, received passports. But then they discovered that the Canadian government would not admit those without funds, unless they had friends who could guarantee that they would not become public charges. For a time it appeared that they would not be able to leave, but fortunately the German government admitted them to Germany temporarily, giving them time to decide on their final destination. The German Reichstag appropriated 6,000,000 Marks, as a loan for the aid of the refugees; various philanthropic organizations, including the German Red Cross, operating in an over-all organization known as "Brüder in Not," helped to care for them, and the Mennonites of Germany and Holland also organized an effectual relief work among them. Benjamin H. Unruh, one of the four Studienkommission delegates from Russia, who had remained in Germany as the agent for the Russian Mennonites and had done great work in the 1922-27 emigration, now served as the liaison with the Mennonites of Western Europe and America in caring for the 1929-30 movement.

Unruh now appealed to the MCC for help. Since immigration to the United States was impossible, and since the door to Canada was also practically closed because of the economic depression, the MCC turned to Paraguay as the best place to which the refugees in Germany might look for a home, and made plans to colonize as many as possible there. Harold S. Bender was then sent to Germany in early 1930 as special commissioner of the MCC, charged with the task of supervising the migration, arranging transportation, and purchasing basic equipment. At the same time C. G. Hiebert was sent to Paraguay. Eventually almost 1,000 of those who had close relatives and friends in Canada found their way there. Another 1,200 settled in Brazil under the auspices of the German government. These were joined later by a group of Russian Mennonite refugees from Harbin, China, making the total immigration to Brazil about 1,300. The remaining 1,700 were brought to Paraguay and settled on land near the Manitoba settlement formed in 1926-27, called the Menno Colony. The new Russian colony was called Fernheim. To these were added about 300 refugees from Harbin, besides a few emigrants from Poland. By 1938 the total Mennonite population in Paraguay was 4,757.

In addition to the 29,000 or more refugees who found their way from Russia to permanent homes in Canada, Brazil, and Paraguay in 1922-32 there were also numerous individuals or small groups who escaped from Russia. One man who was sentenced to forced labor succeeded in having his family brought to him and then together they escaped across Turkestan and the Himalayas to the Mennonite mission at Champa, India. In 1931 three young women fled through eastern Siberia, across the Amur River into China, and then across the Pacific to America. Some fled across the Caucasus into Persia. Others escaped from the lumber camps of northern Russia by British lumber steamer to England or Germany. Many who tried to do so perished in the attempt. Many who remained in Russia also perished at the hands of the Soviets.

Continuing Assistance in Paraguay

Since the colonization of the Mennonite refugees in Paraguay in 1930 the MCC has followed the policy of keeping in close touch with the settlers, providing the assistance necessary in the struggles and hardships of pioneer life. The original expenditure of the MCC in settling the refugees in Paraguay was nearly $200,000. At the time of immigration the settlers had contracted to purchase their land from the Corporación Paraguaya. As time went on, however, it became advisable for the MCC to purchase the Corporación Paraguaya and all its holdings. This purchase of an area more than twenty by twenty-five miles in extent, comprising 330,000 acres, was made in 1937 for some $57,500, with funds loaned to the MCC by the Mennonites of North America. The Paraguayan settlers now purchased their individual holdings from the MCC at one dollar (paper) per hectare, instead of the original eight dollars (gold) which they had contracted for with the Corporación Paraguaya. In 1943 a cancellation of approximately one half of the loan debt was actually carried through.

The program of aid to the new settlers in Paraguay has been continuous and vigorous from the beginning. It was being carried on in reduced form in 1958. Money was sent down for direct relief, but more important was such aid as the sending of a succession of doctors and a dentist for short-term service in the colony and the training of practical nurses and even "practical" dentists. Shipments of new and used clothing, new and used farm implements and tools, a large bulldozer with a trained operator, support of a mental hospital, support of an experimental farm, support of hospitals, and the support for the preparation of schoolteachers of Fernheim Colony in Switzerland were among the forms of aid. In 1957 a group of Pax men was sent down to aid in the construction of the Trans-Chaco roadway. In 1958, through the good offices of the MCC a U.S. government loan of $1,000,000 was made available for colony development through the Paraguayan government.

Spanish Relief

In June 1937 the Mennonite Board of Missions authorized a program of relief to be administered by the Mennonite Relief Committee (MRC) in Spain, which was then engaged in civil war. Funds and clothing were gathered and D. Parke Lantz and Levi C. Hartzler were sent to the field in November 1937, followed later by Clarence Fretz, Lester T. Hershey, Wilbert Nafziger, and Ernest Bennett. When the program closed in the spring of 1940 cash contributions and gifts in kind amounting to about $57,000 had been contributed for this work by the American Mennonites. The Dutch Mennonite Peace Group had also contributed about $1,500 to the work. The MRC work in Spain was closely coordinated with that of the AFSC. In addition to the Mennonite contributions the MRC in Spain distributed a large amount of food supplied by the International Commission for the Assistance of Child Refugees in Spain. The MRC work was on the Loyalist side.

World War II

With the coming of World War II the Mennonite relief ministry was expanded beyond anything which had been conceived in World War I. As a result of the earlier experience the MCC had now developed into an agency coordinating the relief work of Mennonites everywhere. It was an efficient and effective agency which had found its place in a world of relief agencies, both public and private, and was equipped to send funds and workers as needed anywhere in the world, operating independently or in cooperation with other agencies as the occasion might require.

Within three months after the opening of World War II the first MCC representative was in Europe to begin negotiations for a relief program in Poland. A modest work was carried on there from March 1940 until the entrance of the United States into the war. In the spring of 1940 work was opened in southern France for the care of Spanish refugees. Following the German occupation of northern France the work was extended to child feeding in Lyons and other cities and to the care of refugees from German-occupied territory. This phase of the work came to an end in 1942 after the Germans took over the southern French territory.

Early in 1940 the MCC began work in England among refugees from Austria, Poland, and Turkey. The work was later extended to include assistance to old people and children who had been bombed out of their homes in the cities, as well as a ministry to German prisoners of war and other services. The London center was now the European headquarters of the MCC. In addition to carrying on the work in that country plans were being made to open an enlarged work on the continent as soon as the opportunity presented itself. As the war drew to a close the headquarters were moved to Amsterdam and later in 1945 to Basel. (In 1952 it was again moved, this time to Frankfurt.)

As rapidly as possible, now, new relief projects were opened in practically all countries of western Europe. By the end of 1945 the MCC reported 14 workers in France, nine in Holland, three in Belgium, and two at the general headquarters. The work consisted of building reconstruction, emergency relief in the form of food and clothing, and the care of refugees.

In 1946 the MCC work was extended to Germany, Denmark, and Austria. By 1947 the relief program in Germany was in full swing. During that year alone 43 MCC workers distributed 4,538 tons of food, clothing, and other supplies in Germany. The over-all work of the MCC was coordinated with CRALOG (the Council for Relief Agencies Licensed for Operation in Germany), and Evangelisches Hilfswerk, the Protestant relief organization. Assistance to Mennonite refugees from Russia and East Germany was coordinated with German Mennonite relief agencies: Christenpflicht, the south German agency, and the Hilfswerk der Vereinigung Deutscher Mennonitengemeinden, the organization operating in the Palatinate and North Germany. The MCC had food distribution centers in many cities. In June 1947 alone the MCC supplied food to 80,000 people in Germany. Work was extended into Poland (part MRSC), Hungary, Italy, and Belgium (MRSC).

A major portion of MCC work was devoted to Mennonite refugees from the east, who came in large numbers to Denmark, Germany, and even into Holland. In February 1947 the Volendam carried 2,304 of these refugees from Bremerhaven to Buenos Aires on their way to Paraguay. Of these passengers 329 were gathered from Dutch homes, 1,071 from a refugee camp near Munich, and the remainder came from Berlin. In 1947 the MCC opened two refugee camps in Germany, one at Gronau and the other at Backnang. These camps served as processing centers from which as many as possible were moved to Canada and South America, and a few to the United States, in many cases with assistance from the International Refugee Organization. From 1946 to 1951 the MCC assisted a total of 13,980 European refugees in finding new homes in the Western Hemisphere. Of those who remained in Germany permanently, many have been settled in new housing projects with MCC help through its Pax services, in which the labor of young American Mennonites, engaged in alternative service under conscription, served as the down payment for the house which was then financed by the German government. Such housing projects are located at Wedel near Hamburg, Bielefeld, Backnang, and Enkenbach.

Pax units are also located in other countries, as in Greece where the work is devoted to agricultural improvement, in Algeria (MRSC) as a housing project, and in South America where it is road building. Additional forms of aid in Germany and elsewhere in Europe have been maintenance of children's and old people's homes and community centers.

In addition to Europe the MCC and Mennonite relief agencies associated with it had operations following the beginning of World War II in Jordan, Egypt, and Ethiopia in the Middle East. The work in Egypt in 1944-45 concentrated on aid to Greek and Yugoslav refugees; that in Ethiopia on hospital and medical service; and that in Jordan on help to the Arab refugees from Israel. In the Far East following 1942 work was opened in India, China, the Philippine Islands, Java, Sumatra, Japan, Korea, Formosa, Vietnam, and Nepal. One of the most significant projects of the MCC was that in Puerto Rico which began as a Civilian Public Service unit in 1943, but which employed other personnel engaging in medical and hospital work, and in agricultural and community services.

From 1941 through 1950 the MCC and its affiliated organizations expended more than $12,000,000 in cash and kind for relief purposes. To this must be added perhaps several millions more for the resettlement of refugees. Bringing this help in the name of Christ represented a direct personal ministry of perhaps 700 or more men and women, besides occasional short-term commissioners. After 1948 the relief program had passed its crest. Even so, the annual meeting of the MCC in March 1950 reported a total of 156 workers still on the field, distributed as follows: South America 21, Ethiopia 15 (MRSC), Palestine 5, Far East 26, Europe 59. The latter group had 59 workers in Germany, 8 in France, 4 in Belgium, 4 in Italy, 4 in Austria, 5 in Holland, and 7 in Switzerland, the latter constituting the personnel of the headquarters office in Basel.

Relief in some form somewhere seems to be a continuing need. The annual meeting of the MCC in January 1958 reported a total of 211 Mennonite workers on the field in 1957, distributed as follows: relief workers 115, Pax men 96. Of the total 61 were in Germany, with 30 additional in Europe (Austria, France, Holland, Switzerland), 24 were in Paraguay with 11 additional in South America (Brazil, Uruguay, Peru), 14 were in Korea, and 42 additional in the Far East (Vietnam, Indonesia, Formosa, Japan, India, Nepal); 16 were in Jordan and 9 were in Algeria (MRSC).

From such a long list of persons who served in Mennonite relief since 1940 it is impossible to mention by name all who rendered even outstanding service. Among the names which have become almost household words, however, are those of C. F. Klassen, the father of the refugees, who died in the service in Germany in 1954, and Peter and Elfrieda Dyck, who led the refugees on the Volendam to South America in 1947. In 1957 Peter Dyck was serving as general director of the MCC in Europe. The only MCC relief worker who died in the line of duty in Europe was Marie Fast, who lost her life in 1945 in the Mediterranean Sea while assisting in the repatriation of Yugoslav refugees returning from Egypt; however, two Pax boys died in Greece while swimming and one in Africa, and two girls serving under the MCC died in Korea while recreationing.

The world-wide Mennonite relief work which has developed beginning with World War I and especially since the formation of the MCC in 1920 represents both a cause and an effect of a reawakened and an increasingly ecumenical Mennonitism. In 1915 the European and American Mennonites did not know each other and even many of the Mennonite groups in America had little in common. Even in 1925 only two Americans were present at the first Mennonite World Conference in Basel, Switzerland. The events which followed in the wake of World War II, however, changed this picture completely. By the time of the 1957 World Conference at Karlsruhe, Germany, the existence of a world Mennonitism, in which Mennonites from all parts of the world including the younger churches, as those of India and Indonesia, share in common faith and life and work, had become a fact which was recognized by all.

The two-century-old tradition of active relief work in the Dutch Mennonite brotherhood is carried on today by the Stichting voor Bijzondere Noden in de Doopsgezinde Broederschap en Daarbuiten, organized in 1948 as the successor to the prewar Algemeene Commissie voor Buitenlandsche Nooden. It has been active in sending relief to Austria and Germany, and particularly since 1955 in Berlin. It took the lead in organizing the International Mennonite Relief Committee in 1955, with the specific purpose of strengthening the relief work for East Zone Mennonites through the Berlin Mennonite Church.

In Germany the Hilfswerk der Vereinigung der Deutschen Mennonitengemeinden, established in 1948 to help care for the Mennonite refugees from the East (West and East Prussia), has continued to serve especially in aiding the relief work carried on by the Berlin Mennonite Church for the East Zone Mennonites. Mennonitische Heime was organized in 1948 to establish homes for aged refugees, which are subsidized by the German government through per capita per diem payments for inmates. The MCC has also helped by contribution of relief food. Three such homes have been established: Enkenbach, Leutesdorf, and Pinneberg. Additional German Mennonite organizations have been established to work in the field of resettlement of refugees: Mennonitische Siedlungshilfe (1953) and Genossenschaftliches Flüchtlingswerk (1954). -- Guy F. Hershberger

1989 Update

Early Mennonite baptismal vows emphasized the duty of Christians to help those in need. For the purposes of this article " relief work" is defined as the sharing of material and other assistance with those in need in a spirit of love and mutual respect. Many factors have influenced where and how Mennonites have carried out relief during the 30 years, 1956-86. One factor, involvement in World War II, brought new awareness of the degree of human suffering caused by war. It also deepened convictions that relief sharing is a response to God's grace and his call to be reconciling, compassionate servants. Some North American Mennonites saw relief work as a way to prove to the nation that they were not indifferent to the problems of the world and that their peace witness was more than a refusal of military service. The communications media have had a strong impact on relief efforts by bringing the suffering of war to the attention of Mennonites. Relief aid became an opportunity to relate to Mennonite churches around the world, though Mennonites stressed that relief should go to those in greatest need irrespective of race, religion, nationality, or political ideology. These factors stimulated support for a continuing relief effort in many different settings.

Mennonite relief involves a large network of local, regional, national, and international individuals and groups. Thousands of people contribute goods and money, organize fund-raising projects, work in Thrift and Ten Thousand Villages shops, make up school kits for children, manage food banks, help resettle refugees, and organize distributions in consultation with national and church partners. Wherever relief work takes place, citizens of the country in which it is carried out play a very important role.

Relief Work, 1956-1965

In this decade the focus of Mennonite relief work shifted from Europe to Asia, Africa, Central America, and South America. Some refugee housing and migration assistance continued in Europe as did some development programs in Greece and Crete. German, Dutch, and North American Mennonites cooperated in the Internationales Mennonitisches Hilfswerk, which supported the Menno Heim in Berlin. East-West concerns and European-North American Mennonite relationships grew in importance. The Europäisches Mennonitisches Evangelisations Komitee (EMEK) and Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) cooperated in relief projects in Chad and Indonesia. Many patterns of cooperation developed among various Mennonite groups in Europe, as International Mennonite Organization (IMO). In India MCC cooperated closely with Mennonite Christian Fellowship of India (MCSFI) and the Mennonite Service Agency in Bihar which used a Food for Work approach to provide labor for agricultural development.

In this period North American Mennonites were involved with refugee needs in the Middle East, Africa, Hong Kong, and South Vietnam. Earthquake tragedies in Morocco and Chile and a tidal wave in Honduras brought Mennonite assistance to these countries. Zaire (the Congo) with its Mennonite population, its conflicts and emergency and development needs became an important area of Mennonite work. Independence and tribal struggles in Africa and Asia made relief work difficult and sometimes dangerous for nationals and foreign workers. In May 1962 MCC worker Daniel Gerber was taken by a military group from a medical clinic in Vietnam and has not been heard from since then. North American Mennonites helped Paraguayan Mennonites secure a much-needed development loan in 1957, assisted in the trans-Chaco road project completed in 1961, and cooperated with Paraguayan Mennonites in a ministry to Indians. They also participated in a major forestry project in Algeria in the early 1960s. SELFHELP (later Ten Thousand Villages) Crafts, under Edna Byler's leadership, continued to grow. The Teachers Abroad Program (TAP) became an important form of educational assistance, particularly in Africa. In 1962 there were 23 TAP teachers in Africa and in 1965 there were 64, including a number from Europe.

Mennonite Relief, 1966-1975

Mennonite relief during this decade continued to expand in the quantity of relief materials, in long-term development projects, in geographic areas, and in the number of workers. Pax, a program utilizing young single men with a variety of skills, remained an important program until the early 1970s. Many were loaned to other agencies in Africa. For some, Pax service was performed instead of military service.

By 1974 there were 480 persons serving with MCC in 39 countries, including 152 TAP teachers in Africa. In that year material assistance valued at 3.5 million dollars (US) was sent to developing nations. The first SELFHELP Crafts shop was established in Bluffton, Ohio, in 1974. Work with refugees continued or was initiated in the Middle East, Burundi, Sudan, India, Bangladesh, and Vietnam in this period. Power struggles, ethnic rivalries, political and economic oppression, racism, wars and natural disasters helped create over 14 million refugees and displaced persons. Mennonites responded to earthquakes in Peru and Nicaragua and a cyclone along with droughts and floods in India. Nine million East Pakistan refugees streamed into India in 1971 during the Pakistan-Bangladesh war. Mennonites responded with food shipments and initiated long-range development plans to increase food production. Food, medical supplies, and services were contributed to both sides during the Nigeria-Biafra conflict in 1968 and 1969.

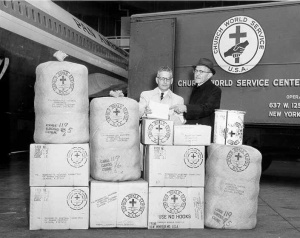

North American Mennonites first went to Vietnam in 1954 at the time of the division of the country. They contributed material aid, provided community and agricultural development assistance, and medical services. In 1965 the situation escalated into a more violent and costly war as the major powers became more deeply involved. American Christians, some of whom felt a measure of responsibility for the destruction, wished to respond. In January 1966 Vietnam Christian Service, a cooperative Protestant relief agency made up of Church World Service, Lutheran World Relief and MCC, was formed. Mennonites furnished 40 percent of the eventual 200 field personnel. MCC, because of its experience in Vietnam and its long peace tradition, was asked to take leadership and did so for the first five years.

Mennonites withdrew from VNCS at the end of 1972 but continued a ministry of reconciling service. After the change in governments in April 1975 four MCC workers remained in Vietnam to demonstrate concern for all of the people of Vietnam. The last worker, a Japanese Mennonite, left Saigon in September 1976. The events in Vietnam raised questions of church and state and of how to respond to those designated as enemies and illustrated the complexities, ambiguities, and challenges of doing relief work when a country is at war. Mennonites believe that Christians and the church belong where there is oppression and suffering.

Beginning in 1965 Mennonites had periodical contacts with representatives of the Provisional Revolutionary Government and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam to interpret peace concerns and express interest in helping the Vietnamese under their governments. Some limited medical supplies were sent, but no regular channels were possible until 1974 when Mennonites began to send substantial material aid, including food, medicines, and school supplies. Agricultural development, including irrigation projects, was the central focus of later assistance.

In this decade Mennonite involvement in Bolivia grew substantially with a focus on agricultural development. New patterns of cooperation between local churches, mission boards, and MCC emerged. Mennonites joined Roman Catholics and others in the fight against poverty and injustice in northeast Brazil. Conflicts resulting from long-term unmet needs in Central America, along with natural disasters, brought visibility to this area. MCC and other Mennonite agencies became increasingly involved, mostly in cooperative efforts with local Mennonite groups and other churches. Relief efforts in southern Africa were affected by apartheid and liberation struggles. Mennonites participated in the United Mission to Nepal, supplying personnel with educational, community development, appropriate technology, and medical skills. In the Middle East Mennonites continued to work on both sides of that region's conflict in services to refugees and in development programs.

In 1974 MCC annual meeting approved the historic Hillsboro Resolution on world hunger. This resolution informed Mennonites of the nature and scope of the food crises, called MCC to give priority in the coming decade to helping developing countries increase their food production, and called Mennonites to find a way to collect food grains for distribution to famine areas when needed. This led to the establishment of the Canadian Food Bank in 1976, to a strengthened food and hunger education program, and to the appointment of an MCC Food Aid Coordinator in 1979. Representatives of North American mission boards and the MCC met together periodically for some years to share information and planning. In a December 1976 meeting the group's name was changed from Council of Mission Board Secretaries to Council of International Ministries. The council, which meets twice each year, is the vehicle through which planning and coordination of Mennonite overseas work is done and reflects increased cooperation between North American mission boards and MCC.

Relief Work 1976-1986

Emergency relief, food production, forestry and water projects, non-formal and formal education, agricultural and community development, appropriate technology, skill training and job creation, SELFHELP Crafts, nutrition and health, church relations, and peace and justice issues dominated this decade. There was some shift toward greater participation of nationals. The aim, though never fully realized, was to achieve a more genuine partnership in which mutual respect, listening and learning were integral to sharing and serving. The awareness that war and violence were primary causes of hunger came into clear focus as a result of Mennonite experience in eastern and southern Africa, Central America, the Middle East, the Philippines, and Southern Asia. As a result MCC overseas secretaries and field representatives moved toward greater integration of peacemaking and justice into all aspects of MCC program. In 1984 a full-time Food and Reconciliation resource person was appointed for Africa.

Relief needs continued to expand in Africa, Asia, and Central America because of wars, natural disasters, economic and trade policies, political oppression, and power manipulations. More and more refugees and displaced persons were created. In a 1979 resolution on the growing refugee problem (then 16 million), MCC called on Mennonites to work on various levels -- services in camps and assistance to those returning to their homes or being resettled in other areas. Mennonites expressed concern to governments about policies and military actions that created refugees and displaced persons and about unfair immigration policies.

Canadian Mennonites have a long history of assisting refugees to resettle in Canada. Between March 1979, when Canada signed a new agreement for the private sponsorship of refugees, until December 1980, 3,300 Southeast Asian refugees were sponsored by Canadian Mennonite and Brethren in Christ congregations. Since that time the focus of Canadian Mennonite sponsorship has broadened to include Central American and East African refugees. MCC, the Conference of Mennonites in Canada, the Mennonite Brethren Conference of Canada, and European Mennonites cooperated in church building and in providing resources for a spiritual ministry to the 13,000 Mennonite Umsiedler/Aussiedler (resettlers/emigrants) who migrated from the Soviet Union to Germany between 1972 and 1985.

Mennonite and Brethren in Christ congregations in the United States sponsored 4,000 refugees from Southeast Asia, Central America, East Africa and Eastern Europe in this decade. Seventy-five Mennonite congregations declared themselves sanctuaries for Central American undocumented aliens (up to 1986). This included physical, emotional, and spiritual assistance and a readiness to risk government prosecution.

Mennonites responded to the food crisis in Ethiopia with relief shipments in 1985 and 1986 totaling 31.4 million pounds (14.1 million kilograms) valued at approximately 5.5 million dollars (US). in Ethiopia, MCC and the Eastern Mennonite Board of Missions have cooperated with the Ethiopian Mennonite Church in relief and development within governmental structures and policies. In 1985 and 1986 Mennonites also sent relief supplies to the provinces of Eritrea and Tigray, two provinces which were engaged in armed resistance to the Ethiopian government, again reaching across political and ideological lines to serve those in greatest need.

In Uganda, Sudan, the Middle East, Central America, Southern Africa, and Cambodia, war and injustices have created suffering, dislocation, fear, hate, and despair. Mennonites, through MCC, have tried to be the reconciling presence as they have carried out relief and development in the midst of turmoil. In this period Mennonites assisted Bangladesh to expand its food production, increase self-help crafts, and create jobs. Relief continues in the socialist countries of Laos, Vietnam, and Kampuchea, whose people suffer from natural disasters and the effects of a long war. Food, medical assistance, and agricultural development are important components of the Mennonite response to these nations that continue to be labeled "enemy" by the United States. Improving international understanding and reconciliation suffuses Mennonite motivation for such efforts. This same spirit energizes the international exchange program and other contacts with the former Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, and China. In 1981 North American Mennonites established China Educational Exchange, composed of Mennonite mission boards, MCC, Mennonite Medical Association, and Mennonite colleges.

The primary administrative channel for relief work of North American Mennonites is MCC International, though MCC Canada administers selective programs overseas within the binational umbrella of MCC. Mennonites in various parts of the world administer relief in different ways -- through their own agencies; through participation in cooperative patterns with MCC, mission boards and national churches; or through other ecumenical channels such as national councils of churches or the World Council of Churches. German Mennonite agencies (Hilfswerk der Vereinigung der deutschen Mennonitengemeinden and Christenpflicht) participate in and support IMO programs and also carry out relief projects of their own. This is also true of Stichting voor Bijzondere Noden, the Dutch Mennonite relief organization. Swiss and French Mennonites have their own relief committees, Schweizerische Mennonitische Organization für Hilfswerke and Caisse de Secours. They support a variety of relief projects, some of which are related to their overseas mission interests. Amish Mennonite Relief, organized in 1955 by Beachy Amish Mennonites in the United States, work in Germany, El Salvador, Belize, and Paraguay. The Brethren in Christ Board of World Missions regularly contributed relief funds to MCC, raised above-budget support for meeting overseas and domestic hunger needs, and organized agricultural projects in some overseas missions. MCC, the largest Mennonite relief agency, contributed 364.5 million pounds (164 million kilograms) of relief materials valued at more than 106 million dollars (US) from 1956 through 1986 to people in 93 countries. Overseas volunteers initially serve two- or three-year terms. Approximately 40 percent of MCC volunteers return for a second or third term. In 1986 there were 510 MCC workers active outside North America, including 19 from non-North American countries.

Summary

In summary we note the following trends in Mennonite relief work since 1956: (1) Response to emergency needs remains a central part of Mennonite relief activity. (2) Long-term development needs such as food production, nutrition, health, education, housing, jobs, ecology, reconciliation, and justice have become increasingly important in Mennonite response to human need. (3) There is a trend toward greater involvement of nationals in need assessment and in planning, administering, and evaluating relief work. This grows out of greater awareness that genuine partnership involves compassion, listening, learning, and mutual respect (service). (4) There is increased cooperation of Mennonite relief agencies with local churches, other church-related groups and non-governmental agencies. (5) There has been significant growth in the purchase of Ten Thousand Villages crafts, relief sales income, informal and adult education, development and use of appropriate technology , integration of peace and justice into relief and development efforts, and education of church constituencies and the public on the broader issues of relief, development and justice. (6) Mennonite relief involvement in socialist countries and Islamic areas has increased. (7) Mennonite personnel now work in many contested and militarized areas. This presents complexities, risks and opportunities. -- Atlee Beechy

Bibliography

Dyck, Cornelius J., ed., with Robert Kreider, John A. Lapp and others. The Mennonite Central Committee Story, 5 vols. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1980-87.

Epp, Frank H., ed. Partners in Service: the Story of Mennonite Central Committee Canada. Winnipeg: MCC Canada, 1982.

Glick, Helen. Spiritsong: MCC twenty-five years in Bolivia. Akron, PA: MCC, 1983.

Hershberger, Andrew, comp., Ervin Hershberger, ed. Amish Mennonite Aid. Plain City, Ohio: Amish Mennonite Aid, 1980.

Hiebert, P. C. and Orie O. Miller. Feeding the Hungry. Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House, 1929.

Horst, Irvin B. A Ministry of Goodwill: a Short Account of Mennonite Relief, 1939-1940. Akron, PA: Mennonite Central Committee, 1950.

Juhnke, James C. "Mennonite Benevolence and Civic Identity." Mennonite Life 25 (January 1970): 34-37.

Krahn, C., J. W. Fretz, and R. Kreider. "Altruism in Mennonite Life," in P. A. Sorokin, Forms and Techniques of Altruistic and Spiritual Growth, a Symposium. Boston, 1954: 309-28.

Kuhler, W. J. "Dutch Mennonite Relief Work in the 17th and 18th Centuries." Mennonite Quarterly Review 17 (1943): 87-94.

Lehman, M. C. Mennonite History and Principles of Mennonite Relief Work, an Introduction, Students Edition With Syllabus and Annotated Bibliography. Akron, PA: Mennonite Central Committee, 1945.

Lind, Tim. "Inquiry into MCC Africa Purpose and Presence, an Unpublished Study and Evaluation of MCC, Africa." Akron, PA: MCC, 1986.

Martin, Luke S. An Evaluation of a Generation of Mennonite Mission, Service and Peacemaking in Vietnam, 1954-1976. Akron, PA: MCC, MCC Peace Section, Eastern Mennonite Board of Missions and Charities.

Mennonite Central Committee Annual Workbook, 1956-86, prepared under supervision of the executive secretary of MCC.

Neff, Christian, ed. Mennonitische Welt-Hilfs-Konferenz vom 31. August bis 3. September 1930 in Danzig. Karlsruhe, 1931.

Proceedings of Mennonite World Conference, esp. Orie O. Miller in 1957 Proceedings, 77-82; C. N. Hostetter in 1962 Proceedings, 245-52; R. W. Kylstra in 1967 Proceedings 194-98; William T. Snyder in 1967 Proceedings, 179-86; Yorifumi Yaguchi in 1972 Proceedings, 122-26; Albert Widjaja in 1978 Proceedings, 81-91; Gilberto Flores in 1984 Proceedings, 154-72; Georgine Boiten-du-Rieu, Elke Hubert, Willi Wiedemann in 1984 Proceedings, 188-208.

"Proceedings of the Consultation on Relief, Service and Missions Relationships, May 7-8, 1964." Akron, PA: MCC, 1964.

Unruh, John D. In the Name of Christ: a History of the Mennonite Central Committee. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1952.

Vietnam Christian Service: Witness in Anguish, a report of an evaluation conference of Vietnam Christian Service, published by Church World Service, 475 Riverside Drive, New York, NY 10115.

Yoder, S. C. For Conscience Sake: a Study of Mennonite Migrations Resulting Rrom the World War. Goshen, IN: Mennonite Historical Society, 1940.

See also the reports and addresses on relief and refugee work in the printed reports of the other Mennonite World Conferences (1936 at Amsterdam, 1948 at Goshen and Newton, 1952 at Basel, 1957 at Karlsruhe).

Additional Information

| Author(s) | Guy F. Hershberger |

|---|---|

| Atlee Beechy | |

| Date Published | 1989 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Hershberger, Guy F. and Atlee Beechy. "Relief Work." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1989. Web. 30 Jan 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Relief_Work&oldid=177254.

APA style

Hershberger, Guy F. and Atlee Beechy. (1989). Relief Work. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 30 January 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Relief_Work&oldid=177254.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 4, pp. 284-291; vol. 5, pp. 760-763. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.