Mexico

Introduction

Mexico is a republic in North America, bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of Mexico. Mexico is the fifth-largest country in the Americas by total area -- 1,972,550 km2 (761,606 square miles). With an estimated population in 2009 of 111,211,789, Mexico is the 11th most populous country and the most populous Hispanophone country on Earth.

The large majority of Mexicans can be classified as Mestizos, having cultural traits and a heritage that is mixed by elements from indigenous and European traditions.

According to the 2000 census, 76.5% of the population is Roman Catholic, 6.3% is Protestant, 3.01% have no religion, 0.3% belong to a faith other than Christianity, and 13.8% were classified as unspecified.

1957 Article

Mexico is a federal republic of North America, though it belongs geographically partly to Central America. It extends southward from the United States to Guatemala and Belize. The Rio Grande River is its northern boundary line. The Sierra Madre mountain ranges extend in the north-south direction shaped like a huge wishbone with two forks reaching north from Mexico City. Between the ranges lie a number of valleys and plateaus of differing altitudes. The country has great diversity of climate because of its location in both temperate and tropical zones and its varied altitudes. Annual rainfall varies from three inches in northern Lower California to 82 inches in the tropics. The country as a whole suffers from a lack of natural water supply. Large areas of Mexico are unproductive. In 1940 only 7.6 per cent of the land area was under cultivation. Of the unproductive land 80 per cent is known as "seasonal" land in that it will produce crops only during the rainy season, which in most parts of the country is from May or June to September. Only about 6.5 per cent of the land does not require irrigation. Much of the farming is done on plateaus at altitudes of 5,000 feet or over. The drop in altitude along the mountains is so sudden that streams tend to flood quickly during rainy seasons and to revert to dry gullies in the winter. Few streams of any length are found on the level plateaus and for this reason in many areas the possibilities for extensive irrigation projects are limited.

Politically Mexico has had a stormy history. Being a Spanish colony, it was for years exploited under the imperialistic colonial system. It has had its national heroes who struggled valiantly to emancipate the country and bring political freedom to its people. The United States governmental organization has been generally the model after which Mexico has patterned. The government, both national and local, in the mid-20th century was less stable and democracy less mature than is the case in the United States and Canada. Nevertheless, noticeable progress was made in the second quarter of the 20th century, in that revolutions were fewer and orderly elections became more commonplace.

The significance of Mexico for Mennonites is in the settlement of over 16,000 Mennonites there. In 1922-1927 several thousand Mennonites from the Old Colony and the Sommerfelder Mennonites in Manitoba (and some from Saskatchewan) immigrated to Mexico. These groups represented the most conservative elements of the Mennonites who had come from Russia to Canada in the 1870s. They left Canada out of protest to the secularization processes, the chief of which was the Canadianization to which they were being subjected in the public schools. The Mennonites were opposed to the requirement to conduct their schools in the English language, which they considered an abrogation of a privilege granted them originally when they immigrated. Rather than surrender what to them seemed freedom of education, they decided to emigrate.

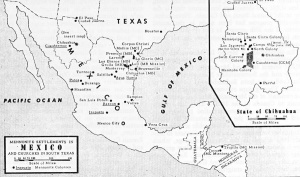

A delegation of six men investigated colonization possibilities in a number of South American countries, but nowhere but in Mexico were they able to secure the desired privileges. Alvaro Obregon, the president of Mexico at that time, by presidential decree granted them the privileges they sought, such as freedom from military service, freedom from the swearing of oaths, freedom to conduct their religious life and observe their church regulations without molestation or restrictions, freedom to establish and conduct their own schools and select their own teachers without hindrance from the Mexican government, and freedom to dispose of property or establish any economic system which they might voluntarily adopt. The largest Mennonite settlement in 1950 was located in the state of Chihuahua, consisting of over 12,000 Mennonites, more than 90 per cent of whom were Old Colony Mennonites. About 6 per cent are Sommerfelders, a slightly less conservative branch. There are also a few Church of God in Christ and General Conference Mennonites. A small settlement of Old Order Mennonites and Old Order Amish from Pennsylvania established in the state of San Luis Potosi in 1944 failed. Some 3,000 (1950) Old Colony Mennonites were located in the state of Durango, 500 miles south of the Chihuahua settlement. A new settlement of Swift Current, Saskatchewan, Old Colony Mennonites and a Kleine Gemeinde group of Manitoba originated in 1948 on the Los Jagueyes ranch northwest of the Cuauhtemoc settlement.

The total Mennonite population of Mexico in 1950 was about 16,000. Almost without exception the Mennonites in Mexico were engaged in agriculture. Their pattern of settlement was according to agricultural villages very similar to the pattern brought from Russia by way of Canada. New land has always been bought in large blocks and redistributed to the purchasers in family-sized farms. The chief crops produced were oats, some corn, beans, and dairy products. A generally diversified type of farming was most common. Mennonites have contributed much to the production of such commodities as butter, cheese, beef, pork, oats, and beans for the commercial market. Fruits and vegetables were grown only in limited quantities on irrigated lands. The few Old Colony Mennonites that engaged in business and industry in towns were not considered members in "good standing." Few of them had shops and stores in the rural villages. The Mennonites engaged in industry and businesses were members of the General Conference Mennonite group. The Church of God in Christ Mennonites had a flourishing mission station in rural Mexico in the central region of the Old Colony settlement.

The future of the Mennonites in Mexico in the 1950s seemed somewhat uncertain. Some thought of Mexico as a somewhat temporary stopping place on a pilgrimage to a yet unknown land, others as a permanent place of settlement. The entire Mennonite settlement in Mexico presented an interesting experiment in the contact of two different cultures. Mexico had a Latin culture, which included the Spanish language, the Roman Catholic religion, and many moral standards and customs alien to those of the Mennonites, who were a Germanic Protestant group with generally higher standards. The influence of the Latin culture was felt by the Mennonites, and outsiders could notice many adaptations that the Mennonites made to it. The Mennonites, though a minority group, made a significant impact on the Mexicans, especially in agricultural methods, and introduced modern farming machinery and highly superior types of livestock. Slowly Mexican neighbors began to imitate these examples. The process of cultural interaction was continuing. The privileges which the Mexican government granted the Mennonites had been scrupulously upheld in the mid-20th century. The severe drought of 1951-1954 placed a very heavy strain on the economic welfare of the settlements. Several hundred returned poverty-stricken to Canada in 1954-1955.

After 1947 the Mennonite Central Committee carried on a program of social welfare and relief, largely for the Mennonites, with headquarters in Cuauhtémoc. Hospital service, primarily in Cuauhtémoc, was a major part of the program. In the drought period considerable direct relief was given, particularly in seed wheat. (See also Old Colony Mennonites.) -- J. Winfield Fretz

1990 Update

Mexico attained its independence from Spain in 1821, and, with the exception of the French Intervention (1862-1867), has been a federal republic largely modeled after the United States. Through the Texas and Mexican Wars (1836 and 1846-1848), and the Gadsden Purchase (1853) Mexico ceded approximately one-half of its original territory to the United States. Its 30 states plus a federal district extend from its frontiers with the United States to Guatemala and Belize, covering an area one-third larger than Quebec or Alaska, twice the size of Egypt. The population was expected to reach 85 million in 1988, and 106 million in 2005. The northern two-thirds of the country, with the exception of Baja California, is a plateau ranging in elevation from 2,700 m. (8,800 ft.) in the south, to 1,000 m. (3,300 ft.) in the north, characterized by a semi-arid to arid climate and a basin-and-range topography, descending to narrow coastal plains on the Gulf of Mexico and Pacific sides, and to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in the south.

Mexico's agricultural potential, as a consequence of its latitudinal span from the lower middle latitudes to the tropics and its highly varied topography, covers a broad range. However, only 12 percent of the national area was classed as arable and, due to shortage of precipitation or water for irrigation, or both, only about 60 percent of the arable land regularly produces crops. Erosion on unirrigated land, and salt contamination on land under irrigation, are major problems.

From 1929 to 2000, Mexico had been governed without interruption by the Institutional (formerly National) Revolutionary Party (PRI). By Latin American standards, Mexico has had relatively stable political conditions. The PRI had exercised a highly interventionist (but non-Marxist) policy in economic affairs and social development, styling Mexico under its rule as a "guided democracy." The president, whose term of office is six years, and who may not succeed himself, is invested with very great powers.

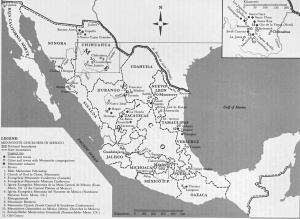

Mennonite settlement in Mexico began in 1922, following the granting of a Privilegium (privileges) by the Mexican government under the leadership of President Alvaro Obregón. The Privilegium was similar to those extended to the Mennonites in Russia and elsewhere in Latin America. By 1927 some 7,000 Old Colony and Sommerfeld Mennonites from Manitoba and Saskatchewan were living in the Manitoba Colony (1922), Swift Current Colony (1922), and Santa Clara Colony (1922) in Chihuahua State; and at Patos (1924), also known as the Hague Colony, in Durango State. These groups had emigrated from Russia to Canada in the 1870s in response to offers of reserved homestead lands and privileges and immunities equivalent to those inherent in the Privilegium held in Russia. When they perceived developments in Canada, especially the anglicization and secularization of the school system from 1916 onward, as an invasion of these privileges and immunities, and as a threat to influence and authority by community leaders, they left Canada. Following a concerted search throughout North and South America, Mexico proved to be the only country besides Paraguay willing to accept them on their terms, and Mexico became the choice of all of the Old Colony Mennonites and a minority of Sommerfeld Mennonites.

The pioneer years were very difficult. Civil order was generally in disarray in the first decades after the revolution of 1910-1920. The crops and land management practices to which the Mennonites were accustomed were only marginally applicable to the semi-arid highland environment.

By 1940, despite the return to Canada of approximately 20 percent of the colonists, and despite many deaths, especially of infants, the colonies needed more land. Since that time the Mennonites of Mexico have been continuously in search of land. While their numbers have increased almost 500 percent from 1940 to the late 1980s, to an estimated 45,000-50,000, their land holdings have increased by only slightly more than 100 percent. From 1948 to 1952, some 150 families (595 persons) of Kleine Gemeinde (Evangelical Mennonite Conference) affiliation from Manitoba established the Quellenkolonie (Quellen Colony) on 142 sq. km. at Los Jagueyes in Chihuaua, 40 km. north of the Swift Current Colony, after obtaining inclusion in the Privilegium covering the Old Colony and Sommerfelder.

Other, smaller groups of Mennonites, from Russia, the United States, and Canada, have made attempts at colonization in Mexico. In 1924 three families of Kleine Gemeinde affiliation from Kansas established a small settlement north of the Manitoba Colony. Most of them soon returned to the United States; the rest were absorbed by the Old Colony. Beginning in 1924 various attempts by the Kansas-based Mennonite Board of Colonization to resettle in Mexico several groups of refugees from the Soviet Union failed as opportunities to enter the United State or Canada opened up. Those attempted settlements were, in the States of Coahuila, Chihuahua, Guanajuato, Durango, and Baja California. Ultimately only about 6 out of 200 Rußländer families remained in Mexico (Mennonitengemeinde zu Mexico).

In 1927 four related families of Church of God in Christ, Mennonite (Holdeman) affiliation from Oklahoma established a small settlement at Cordovana, north of the Swift Current Colony. This became a Church of God in Christ mission settlement in 1945. In 1943 six families of Mennonite Church (MC) and Amish background came first to Chihuahua, then attempted to settle at Rascón, and later at Rayóon, in San Luis Potosi. The survivors returned to the United States in 1946.

In 1948, 38 families (246 persons) of Old Colony affiliation from Manitoba and Saskatchewan participated as a separate group in the Quellenkolonie venture of the Kleine Gemeinde. Most of them shortly returned to Canada; of those remaining all but a few left the colony.

Agriculture as the economic basis of the colonies and an agrarian ethic relating status to property ownership remained dominant. Nevertheless, food processing and services related to agriculture have achieved wide representation. Dominant in the secondary sector was cheese production, which became the economic mainstay in all but a few of the colonies. Dairying helped maximize returns from agriculture because it made use of crop residues. Since the 1960s wheat production increased substantially while corn, oats, and bean production decreased proportionately, especially in Chihuahua. Production of tree crops, particularly apples, also grew. Since about 1955 Mennonite crop production has been fully mechanized.

Non-colonizing Mennonite and non-Mennonite groups have increasingly established a presence in and near the Mennonite colonies. In 1947 the Mennonite Central Committee established a center in the town of Cuauhtémoc to help Old Colony Mennonites in Chihuahua who were suffering after widespread crop failure. This center expanded to include medical services and, ultimately, under the auspices of the General Conference Mennonite Church (GCM), state-accredited primary schools, a secondary school, and the Blumenau congregation (GCM). During the 1950s the Mennonite Brethren established a clinic at Nuevo Ideal (Patos), in Durango State, which offered services to the Old Colonists on the same basis as the Mexican populace. Gradually, a Mennonite Brethren congregation, supporting an elementary school, since 1973 located within the Patos colony, emerged.

Divergent opinions about innovation in economic and technological areas stimulated tensions within Old Colony congregations. A number of other religious groups established a proselytizing, evangelizing presence (Manitoba Colony) that attracted marginalized Old Colonists. Among these groups are the Church of God, the Seventh Day Adventists, Pentecostals, and the Evangelical Mennonite Mission Conference (EMMC).

In Mexico conservative Mennonites encountered a social and political environment more like that of the Russian Empire than that of Canada. In Mexico, within the provisions of the Privilegium, it proved once more possible to establish and maintain aloofness, if not isolation. The host society was very different in language, culture, and religion, and was so structured politically that ultimate recourse maybe had to a final arbiter in the person of the president. After more than six decades the Mennonites in the 1980s were significantly influenced by the host society, but not in ways that made great inroads on the traditional aloofness between the Mennonites and Mexican society. Social contacts were still minimal, and intermarriage was rare. The government adhered to the terms of the Privilegium to a very high degree, although in dealing with occasional tensions between Mexicans and Mennonites it found itself in the political and moral dilemma of adjudicating between citizens with rights, and aliens with privileges. Nevertheless, perceived threats to their status have provided considerable basis for emigration, most notably to Belize in the late 1950s, and to Bolivia and Paraguay in the 1960s and 1970s. Examples of points of tension with the government included the proposed universal implementation of a social security system in the 1950s, and several subsequent cases in which Mennonites had to forfeit lands with defective title to ownership. More profound appeared to have been the gradual dissolution of internal solidarity due to increasing divergence of opinion in sectarian and secular matters. This stimulated some migration within Mexico, and a great deal to new frontiers in Bolivia and Paraguay. Also, there has been a persistent flow, mostly to Canada, some to the United States, and, since 1986, to Argentina, primarily for economic reasons. The majority of Mennonites still in Mexico in the late 1980s, however, entertained little thought of emigration, and their continuing presence and the associated economic impact upon the regions in which they have settled, appeared to be assured. -- H. Leonard Sawatzky

2020 Update

In 2020 the following Mennonite groups were active in Mexico:

| Denomination | Members in 2006 |

Congregations in 2006 |

Members in 2009 |

Congregations in 2009 |

Members in 2012 |

Congregations in 2012 |

Members in 2020 |

Congregations in 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altkolonier Mennonitengemeinde (Mexico) | 17,200 | 19,450 | 20,650 | 21,916 | ||||

| Asociación Religiosa Igelsia Evangélica Hermanos en Cristo de México | 189 | 7 | 253 | 8 | 325 | 11 | 750 | 10 |

| Conferencia de Iglesias Evangélicas Anabautistas Menonitas de México | 500 | 14 | 550 | 14 | 820 | 11 | 510 | 11 |

| Conferencia Evangélica Misionera de México | 450 | 15 | 480 | 16 | 480 | 16 | 500 | 13 |

| Conferencia Menonita de Mexico | 697 | 3 | 709 | 4 | 855 | 4 | 1,150 | 5 |

| Conferencia Misionera Evangélica | 325 | 6 | 450 | 7 | 650 | 8 | ||

| Convención de Iglesias Evangélicas Menonitas del Noroeste de México | 346 | 14 | ||||||

| Evangelical Mennonite Mission Conference, Mexico | 97 | 3 | ||||||

| Iglesia Cristiana de Paz en México | 350 | 7 | 200 | 7 | 822 | 9 | 622 | 9 |

| Iglesia de Dios en Cristo Menonita (Mexico) / Church of God in Christ Mennonite |

354 | 23 | 363 | 23 | 354 | 25 | 373 | 27 |

| Iglesia Evangélica Menonita del Noroeste de México / Convención de Iglesias Evangélicas Menonitas del Noroeste de México |

278 | 12 | 346 | 14 | 346 | 14 | ||

| Iglesia Evangélica Menonita en Mexico | 170 | 7 | 260 | 11 | 200 | 8 | 210 | 6 |

| Kleingemeinde in Mexiko | 2,150 | 12 | 2,800 | 14 | 2,800 | 14 | 3,000 | 21 |

| Nationwide Fellowship Churches (Mexico) | 208 | 5 | 208 | 5 | ||||

| Reinländer-Gemeinde | 1,350 | 1,675 | 1,675 | 1,837 | 3 | |||

| Sommerfelder Mennonitengemeinde (Mexico) | 2,043 | 2,075 | 2,075 | 2,075 | ||||

| Unaffiliated Congregations | 130 | 6 | 137 | 5 | 184 | 5 | 80 | 2 |

| Total | 25,958 | 29,277 | 32,036 | 34,573 |

See also: Old Colony Mennonites (chart of various colonies); Iglesia Evangélica Menonita de la Mesa Central de Mexico; Iglesia Evangélica Menonita del Noroeste de Mexico; Evangelical Mennonite Conference; Kleine Gemeinde (Latin America); Mennoniten Gemeinde zu Mexico; Evangelical Mennonite Mission Conference; Sommerfeld Mennonites ; Casas Grandes Colonies (Buenos Aires, El Capulin, Buena Vista, Las Virginias, El Cuervo); Cuauhtémoc; Durango Colony (Nuevo Ideal); Manitoba Colony; Swift Current Colony; Nord Colony; Potosi-Saltillo Colony; Zacatecas Colonies (La Batea, La Honda, Campeche).

Bibliography

Fretz, J. Winfield. Mennonite Colonization in Mexico, an Introduction. Akron, 1945.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. III, 120-23.

Kraybill, Paul N., ed. Mennonite World Handbook. Lombard, IL: Mennonite World Conference, 1978: 227-32.

Mennonite Brethren Yearbook (1981): 115-16.

Mennonite Life published the following articles on Mexico:

Vol. 2 (April 1947) contains the articles:

Fretz, J. W. "Mennonites in Mexico."

Stoesz, A. D. "Agriculture Among the Mennonites in Mexico."

Wiebe, C. "Health Conditions Among the Mennonites in Mexico."

Hiebert, P. C. and W. T. Snyder. "Are the Doors of Mexico Open to Mennonite Immigrants?"

Schmiedehaus, W. "Mennonite Life in Mexico."

Vol. 4 (October 1949):

Schmiedehaus, W. "New Mennonite Settlements in Mexico."

Reimer, P. J. B. "From Russia to Mexico—The Story of the Kleine Gemeinde."

Vol. 7 (January 1952):

Burkhart, Charles. "Music of the Old Colony Mennonites [in Mexico]."

Mennonite World Conference. "Global Map: Mexico." Mennonite World Conference. Web. 5 April 2021. https://mwc-cmm.org/global-map.

Mennonite World Conference. "Mennonite and Brethren in Christ Churches Worldwide, 2009: Latin America & The Caribbean." 2010. Web. 28 October 2010. [broken link].

Mennonite World Conference. MWC - 2006 Caribbean, Central and South American Mennonite & Brethren in Christ Churches. [broken link].

Mennonite World Handbook Supplement. Strasbourg, France, and Lombard, IL: Mennonite World Conference, 1984: 83-88.

Mennonite Weekly Review (23 June 1988): 8 (30 June 1988): 6 (7 July 1988): 6.

Quiring, W. Im Schweisse deines Angesichts. Steinbach, 1953.

Redekop, Calvin W. The Old Colony Mennonites. Baltimore, 1969.

Sawatzky, H. Leonard. Sie Suchten eine Heimat. Marburg, 1986.

Sawatzky, H. Leonard. They Sought a Country. Berkeley, 1971.

Schmiedehaus, W. Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott. Der Wanderweg eines christlichen Siedlungsvolkes. Cuauhtémoc, 1948, Winnipeg, 1982.

Warkentin, Abe. Compiler. Strangers and Pilgrims. Steinbach, MB: Die Mennonitische Post, 1987.

Wikipedia. "Mexico." Web. 8 November 2010. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mexico.

| Author(s) | J. Winfield Fretz |

|---|---|

| H. Leonard Sawatzky | |

| Date Published | November 2010 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Fretz, J. Winfield and H. Leonard Sawatzky. "Mexico." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. November 2010. Web. 28 Mar 2025. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Mexico&oldid=171102.

APA style

Fretz, J. Winfield and H. Leonard Sawatzky. (November 2010). Mexico. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 28 March 2025, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Mexico&oldid=171102.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 3, pp. 663-664; vol. 5, pp. 580-582. All rights reserved.

©1996-2025 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.