United States of America

Readers should note that this article was written in the late 1950s.

Introduction

With a total of ca. 152,000 baptized members in all groups, the Mennonites of the United States in 1957 constituted by far the largest national body of Mennonites in the world, the next largest being Canada with 51,000, followed by the Netherlands with 39,000. Of the twelve distinct bodies in the United States (plus several fragmented groups totaling less than 100 members), four are major: the Mennonite Church (MC) with 71,000 (this was the sole body in America until 1812 except for a small group of Amish); the General Conference Mennonite Church (GCM) with 35,400 (organized in 1860, one section having started by a schism from the MC group in 1847); the Old Order Amish Mennonites with 17,000 (unorganized, but separated from the total Amish Mennonite group in ca. 1855-80); and the Mennonite Brethren (MB) with 11,600 (established in Russia by schism in 1860, established in the United States by immigration 1874-76). Six of the remaining 8 smaller bodies range in size from 4,300 to 1,600; these are (1) the Krimmer Mennonite Brethren (KMB) with 1,600 (established in Russia by schism in 1869, immigrated to Kansas in 1874), and five others, all established in the United States by schism, three from the Mennonite Church (MC) - (2) the Church of God in Christ (CGC), Mennonite (1859) with 4,300, (3) the Evangelical Mennonites (1864) with 2,300, (4) the Old Order or Wisler Mennonites (1871-93) with 4,000 - (5) the Beachy Amish by schism from the Old Order Amish (1927 ff.) with 2,400, and (6) the Evangelical Mennonite Brethren by schism from the GCM group in 1889 with 1,600. The two remaining groups, both very small in number and declining in size, originated by schism from the Mennonite Church (MC) in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, that is, the Reformed Mennonites (1812) with 600, and the Stauffer Mennonites (1845) with 360. Beyond the 12 organized bodies are a number of scattered unaffiliated congregations, most of which are in close relationship with other organized groups, and which for statistical purposes are counted with them. Since the Mennonite Brethren in Christ have changed their name (1947), and wish not to be considered Mennonites, although they had a Mennonite origin (1875 schism from MC), they are omitted from this discussion.

Immigration

The Mennonites of the United States, all of course deriving from Europe by immigration at various times, represent basically two ethnic-culture groups, the Swiss-South German and the Prusso-Russian (largely direct from Russia). The former constitute roughly two thirds, the latter one third, of the total immigrant number. The Swiss-South Germans constitute the entire membership of the (MC) and Amish bodies and all branches formed from them (except the (CGC) group), and about one half of the GCM group. The Prusso-Russians constitute the entire membership of the MB, KMB, and EMB groups, almost all of the CGC group, and about one half of the GCM group. Geographically, all the Mennonites living east of the prairie states except Minnesota are of Swiss-South German stock, while the Mennonites of the prairie states (North and South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Minnesota) are 85 per cent Prusso-Russian, and those in the Mountain and Pacific states are about 60 per cent Prusso-Russian.

Finally it should be noted that of the Swiss-South German group, less than half (ca. 50,000) represent descendants of the 18th-century immigrants from Switzerland and the Palatinate, while the remaining half represent descendants of the 19th-century (first half) largely Amish immigrants from Switzerland, Alsace-Lorraine, Palatinate, Bavaria, and Hesse, plus a substantial group of Swiss background who came in 1874-1875 from Volhynia (western Russia) and Galicia (Austria). The Prusso-Russian immigrants practically all came in 1874-1880; a very small late arrival group came in 1930 from eastern Russia via Manchuria. The GCM Church is the only group composed of mixed ethnic strains from all European backgrounds and immigration periods.

A very small Lower Rhine element (of Dutch type and connection) constituted the first Mennonite immigration to America in 1683-1702; they have been assimilated completely into the MC and GCM Swiss-German groups in the Franconia area.

Although comprehensive immigration statistics were not kept and can be only roughly reconstituted from the available records, the following table of the successive waves of Mennonite immigration to America is approximately correct.

| 1 | Lower Rhine to Germantown | 1683-1702 | 200 |

| 2 | Swiss and Palatine Mennonites to Eastern Pennsylvania | 1707-1756 | 4,000 |

| 3 | Swiss and Palatine Amish to Eastern Pennsylvania | 1738-1756 | 200 |

| 4 | Alsace-Lorraine, Hessian and Bavarian Amish to Western Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, Iowa | 1815-1860 | 2,700 |

| 5 | Swiss Mennonites to Ohio and Indiana | 1817-1860 | 500 |

| 6 | Palatine Mennonites to Ohio, Illinois, and Iowa | 1825-1860 | 200 |

| 7 | Prussian Mennonites to Nebraska and Kansas | 1874-1880 | 300 |

| 8 | Russian Mennonites to the prairie states | 1874-1880 | 10,000 |

| 9 | Russian Mennonites to Reedley, California | 1930 | 200 |

| 10 | Scattered individuals (second half of 19th century) from Germany, Switzerland, France, and Russia to states west of the Mississippi | 200 | |

| 11 | Total immigrants | 18,500 |

Since the total immigrant group, except for a few in the late 19th century from France, was German-speaking, the Mennonites of the United States long remained German in language and in cultural orientation. The major transition to English began about 1890 east of the Mississippi, but not until after 1900 in the Russian group in the prairie states. By the end of World War I, due in part to repressive measures in many local communities against the German language during the war, the transition was relatively complete. However, the Old Order Amish have never surrendered the German, either in their worship, or in the Pennsylvania-German dialect in their homes.

By internal migration the eastern Pennsylvania Mennonites spread west to Ontario, Ohio, and Indiana, and southward to Maryland and Virginia in the first half of the 19th century. A smaller stream of migrants continued westward to Missouri and Kansas, and finally reached the Pacific Coast in Oregon by the turn of the 20th century. Amish from eastern Pennsylvania moved westward about the same time to central Pennsylvania (Mifflin County) and Ohio, with a few going further west. The newer 19th-century Alsatian Amish immigration settled in western Pennsylvania (Somerset County), Ontario, Ohio, and Illinois, and moved on in part to Iowa and Nebraska about the middle of the 19th century and later. However, not more than a fifth of the Swiss-South German Mennonite and Amish stock from the Eastern and North Central states finally landed west of the Mississippi. The Swiss and South German Mennonites who came to Ohio in the first half of the 19th century did not join substantially in the westward migration. A small movement to Florida from the Eastern and North Central states developed after World War I but especially after World War II.

The Russian group also joined in the internal westward migration, but not till the 20th century, some going south to Oklahoma when it was opened for settlement in 1892, but many more going to the Pacific Coast, particularly to California (1897 ff.) but also to Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, with a few going north into Montana. None went to Florida.

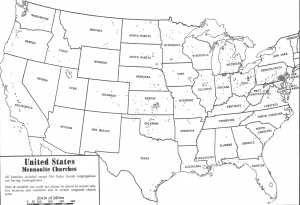

Thus by immigration from Europe at different times to different areas of the country, and by later internal migration westward, Mennonites have spread across the country from coast to coast, and are now located in 25 states, the only major areas missed being New England and the South and Southwest. Mission expansion has led to a light occupation of even these areas, chiefly by the MC group, so that in 1957 forty states out of the 48 (missing Maine, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Utah, Nevada, and Wyoming) and Washington, D.C., had a Mennonite population. The following table lists the distribution of baptized membership throughout the country by states and groups.

| State | Mennonite Church (MC) | General Conference Mennonite (GCM) | Mennonite Brethren (MB) | Old Order Amish (OOA) | Beachy Amish | Evangelical Mennonite Brethren (EMB) | Krimmer Mennonite Brethren (KMB) | Church of God in Christ, Mennonite (CGC) | Evangelical Mennonite (EM) | Reformed Mennonite | Old Order Mennonite | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 87 | 87 | ||||||||||

| Arizona | 163 | 20 | 183 | |||||||||

| Arkansas | 85 | 67 | 12 | 164 | ||||||||

| California | 274 | 1,385 | 4,376 | 142 | 238 | 521 | 6,936 | |||||

| Colorado | 708 | 7 | 153 | 34 | 902 | |||||||

| Delaware | 408 | 240 | 648 | |||||||||

| Florida | 528 | 95 | 623 | |||||||||

| Georgia | 13 | 105 | 97 | 215 | ||||||||

| Idaho | 293 | 384 | 109 | 786 | ||||||||

| Illinois | 3,443 | 2,157 | 730 | 408 | 76 | 434 | 52 | 7,300 | ||||

| Indiana | 7,905 | 2,260 | 3,195 | 448 | 739 | 24 | 302 | 14,873 | ||||

| Iowa | 3,289 | 830 | 794 | 52 | 38 | 5,003 | ||||||

| Kansas | 1,631 | 11,141 | 2,068 | 350 | 279 | 411 | 2,322 | 145 | 18,347 | |||

| Kentucky | 123 | 123 | ||||||||||

| Louisiana | 81 | 122 | 203 | |||||||||

| Maryland | 1,793 | 178 | 27 | 1,998 | ||||||||

| Michigan | 2,413 | 180 | 244 | 32 | 20 | 347 | 64 | 52 | 3,352 | |||

| Minnesota | 364 | 1,783 | 465 | 306 | 2,918 | |||||||

| Mississippi | 87 | 87 | ||||||||||

| Missouri | 514 | 127 | 200 | 96 | 937 | |||||||

| Montana | 220 | 529 | 203 | 98 | 1,050 | |||||||

| Nebraska | 1,370 | 1,731 | 335 | 157 | 3,593 | |||||||

| New Jersey | 15 | 15 | ||||||||||

| New Mexico | 14 | 13 | 27 | |||||||||

| New York | 1,332 | 113 | 29 | 1,474 | ||||||||

| North Carolina | 44 | 170 | 214 | |||||||||

| North Dakota | 251 | 313 | 525 | 4 | 25 | 1,118 | ||||||

| Ohio | 9,808 | 2,591 | 6,586 | 225 | 58 | 853 | 150 | 341 | 20,612 | |||

| Oklahoma | 257 | 1,857 | 2,287 | 160 | 424 | 4,985 | ||||||

| Oregon | 1,860 | 909 | 507 | 28 | 119 | 368 | 13 | 3,804 | ||||

| Pennsylvania | 26,580 | 4,061 | 4,168 | 692 | 309 | 3,272 | 39,082 | |||||

| South Carolina | 13 | 13 | ||||||||||

| South Dakota | 26 | 2,438 | 140 | 141 | 778 | 33 | 3,556 | |||||

| Tennessee | 48 | 61 | 34 | 143 | ||||||||

| Texas | 151 | 18 | 331 | 500 | ||||||||

| Vermont | 43 | 43 | ||||||||||

| Virginia | 3,820 | 160 | 259 | 225 | 4,464 | |||||||

| Washington | 614 | 187 | 801 | |||||||||

| West Virginia | 673 | 673 | ||||||||||

| Wisconsin | 130 | 50 | 60 | 240 | ||||||||

| Washington, D.C. | 40 | 40 | ||||||||||

| Total | 70,884 | 35,315 | 11,644 | 17,273 | 2,380 | 1,625 | 1,597 | 4,389 | 2,269 | 616 | 4,140 | 152,132 |

Spiritual Development

In the United States the oppressed Mennonites of Central Europe for the first time had the privilege of full liberty of conscience and unrestricted cultural and economic development, guaranteed first of all by William Penn’s Quaker Pennsylvania, to which the 18th century emigration was exclusively directed. Moreover the nonresistant Mennonites found in Pennsylvania full sympathy for their position on rejection of warfare and the oath, since the Quakers held the same basic position on these points. Later by constitutional provision in the federal constitution and in most state constitutions these privileges were firmly anchored. The unlimited resources of the new world in fertile lands, forests, and minerals were almost literally free for the taking by the pioneers, and those great economic opportunities continued for two centuries as the frontier moved westward; hence Mennonites of all later immigrant groups also had equal rights to them.

Since all Mennonite immigrants to America were farmers, except the small early Lower Rhine group, and since unoccupied land was plentiful, the typical Mennonite pattern of settlement in America was in fairly compact groups of single farmsteads, though not in exclusive colonies nor in villages. Practically no Mennonite city settlements nor city congregations were founded until the 20th century, with a few exceptions, such as Philadelphia (GCM) in 1865, Elkhart, Indiana (MC) in 1871, Lancaster, Pennsylvania (MC) in 1879. Accordingly the American Mennonites long remained an exclusive rural group, stable, conservative, prosperous; only in the second quarter of the 20th century has any really substantial urbanization set in. Now many have established small businesses and even industries, have entered the professions or have become laborers. By 1955 the proportion of urban population had passed 50 per cent in practically the entire area east of Mississippi and reached 85 per cent in the Franconia area of eastern Pennsylvania. The typical German virtues of thrift, hard work, sobriety, and community solidarity, reinforced by the Mennonite emphasis on nonconformity to the world, mutual aid, simplicity, love, quietness, united in creating a typical American Mennonite character, with a strongly conservative social and religious bent, and a strong group loyalty. This character, coupled with a strong emphasis on tradition, resulted in a notable emphasis on simplicity and no worldliness that not only developed into a traditional pattern of simplicity in dress, form of worship, and general way of life, but made possible a relative insulation from the surrounding American culture. The absence of a trained ministry, and the general negative attitude toward higher education, meant further that few influences toward change in the traditional pattern entered the group by the educational route. This contributed to a relative stagnation in church life.

As a result of these several factors the great opportunity in America for a free unfolding of the Anabaptist genius was partly lost, and the heritage lay relatively dormant and unfruitful. The carry-over from the long time of persecution in Europe, reinforced by preoccupation with the hardships of pioneering, and by cultural isolation through the retention of the German language in an English environment, contributed much to the loss of a sense of mission. The basic Mennonite heritage of doctrinal and ethical principles was, however, maintained. All Mennonite immigrants of whatever period brought with them a strong commitment to nonresistance, the greater proportion having left Europe to a large extent because of pressure on this very point by the governments and the cultures from which they came. This was particularly true of the 19th-century movements from France, South Germany, Prussia, and Russia, but also to some extent for the earlier 18th-century emigration.

In the second half of the 19th century new influences came to bear on the established Mennonite communities in the East, while the newer immigrants to the mid-west from Russia and South Germany brought with them a more vigorous piety and a more aggressive spirit. American revivalism of the Moody type, the Sunday school, outside Protestant literature, the influences from the growing general Protestant emphasis on missions, evangelism, temperance, etc., played their part in breaking through the barriers of isolation and opening up Mennonites in many places to change and progress. But this was not without stress and strain. Formerly large numbers were simply lost to the church, to join other Protestant denominations. Now new life and progress retained many more, but also led to serious divisions in the second half of the 19th century; e.g., Old Order Amish, Old Order Mennonite, Mennonite Brethren in Christ, Defenseless Mennonite, and Oberholtzer-GCM (earlier in the century).

By the beginning of the 20th century a genuine awakening and revival was occurring, with a warmer type of piety, emphasis on Christian experience, activity in evangelism, missions, education, and publication, better ministerial service (trained ministry came later), and a recovering sense of mission. This revival has affected all the groups, except the Old Order Amish and Old Order Mennonite, who have resisted all change and remained traditional, a block of at least one eighth of the total United States Mennonite membership. The second quarter of the 20th century has added to the revival a remarkable development in relief work and social service, at first largely under the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC), but now spreading into most of the larger groups directly.

Missions have had a remarkable development in all the American Mennonite groups (except the two Old Order groups) in spite of a late start at the turn of the 20th century. By 1957 a total of 638 Mennonite missionaries were at work in 27 foreign countries and Puerto Rico and Alaska, with a total of over 50,000 baptized members on all fields. China, India, East Africa, and the African Congo were the oldest and strongest fields.

Foreign relief work under the Mennonite Central Committee (organized 1920) had also reached striking proportions, largely after World War II, with operations in a maximum of 20 different countries by over 350 workers at one time in 1948-50, although the famine relief program in Russia in 1920-22 was itself a major effort. The operation of Civilian Public Service by united Mennonite effort under the MCC during World War II reached a maximum of over 4,000 Mennonite conscientious objectors in 1944. After World War II the movement for mental health work resulted in the establishment of three mental hospitals under MCC, and one under the Lancaster Conference (MC). A further outgrowth of the World War II experience was the Voluntary Service program, partly under MCC and partly under the major conferences (MC, GCM, and MB), in which hundreds of Mennonite youth served in a variety of social service and mission-related projects in short summer terms and longer terms of one or two years. Pax Service abroad for conscientious objector men resulted in over 200 serving in reconstruction and other service in Germany, Greece, Korea, and elsewhere, under MCC direction.

Another prominent and highly important development in American Mennonitism in the 20th century has been the forward movement in higher education, with the establishment of colleges and seminaries. Full four-year college programs were established in the three major groups as follows with the year of granting the first B.A. degree: MC - Goshen 1910, Eastern Mennonite College 1948; GCM - Bethel 1912, Bluffton 1915; MB - Tabor 1922. Junior Colleges were also established at Hesston (MC, 1915) and Freeman (GCM, 1923). The following seminaries have been established: Witmarsum (called Mennonite Seminary as part of Bluffton College 1915-21, independent at Bluffton, Ohio 1921-36); Tabor College of Theology (MB, as part of Tabor College 1924-1955) at Hillsboro, Kansas; Goshen College Biblical Seminary (MC, as part of Goshen College at Goshen, Indiana, 1933- ); Mennonite Biblical Seminary (GCM, in affiliation with Bethany Biblical Seminary in Chicago 1945-1958, in Elkhart, Indiana, 1958- ); and Mennonite Brethren Biblical Seminary at Fresno, California, in 1955- . The Mennonite Brethren Bible College (1944- ) and the Canadian Mennonite Bible College (GCM, 1947- ), both Winnipeg, offer theological curriculums, the former Th.B., the latter B.C.E. At least 15 church high schools and 80 elementary schools have also been established, largely since 1945 and chiefly in the MC group, in addition to a number of Bible schools and two Bible Institutes (Grace at Omaha, inter-Mennonite; Fresno, MB, 1955). These schools, particularly the colleges, have become very influential in the Mennonite brotherhood in the United States, and have contributed much to the strength of church life, witness, and service.

In publication the three major groups have developed publishing houses (MC - Scottdale, Pennsylvania, 1908; GCM - Berne, 1884; Newton, 1949; MB - Medford, Oklahoma, 1904, Hillsboro, Kansas, 1913); although the Scottdale House with its larger constituency has developed the only major American Mennonite publishing enterprise with substantial books by Mennonite authors. A majority of literary production by American Mennonite writers has been by authors from the Mennonite Church (MC). Outstanding American Mennonite authors have been C. H. Wedel (GCM, d. 1913), Daniel Kauffman (MC, 1865-1944), C. Henry Smith (GCM, 1875-1948), John Horsch (MC, 1867-1941), J. C. Wenger (MC, 1906- ), G. F. Hershberger (MC, 1897- ). The various Mennonite bodies large and small have almost all established their own periodical organs, of which the chief are the following: MC - <em>Gospel Herald</em> (circulation 18,500); G.C.M. - The Mennonite (circulation 15,000); MB - The Christian Leader 1937 (circulation 2,500) and Zionsbote 1884 (circulation 2,000). Noteworthy other periodicals are the inter-Mennonite Mennonite Weekly Review 1923 (circulation 21,000), Mennonite Life 1946 (GCM, circulation 2,500), and the Mennonite Quarterly Review 1927 (MC, 750).

The growth of awareness of the historic Anabaptist heritage and the attempt to work out its implications theologically and practically, which marked the American Mennonites generally in the second quarter of the 20th century, has helped to awaken most of the groups to the danger of pure traditionalism on the one side, and on the other side the danger of undue influence from outside movements in theology and piety. This has also contributed to the building of a solid foundation for better mutual understanding and co-operation among the various American Mennonite groups.

The striking growth in the number, quality, and significance of inter-Mennonite relationships and cooperative activities, is a marked feature of the mid-20th century in American Mennonitism (see Inter-Mennonite Relations). One result of the general drawing together has been a series of group reunions or mergers, including Mennonite-Amish Mennonite (MC, 1915-25), Mennonite-Conservative Amish (MC, 1955), General Conference-Central Conference (GCM, 1945), Evangelical Mennonite-EMB (only partially completed) (1953), Mennonite Brethren-Krimmer Mennonite Brethren (MB, 1959).

The Mennonites of the United States in 1957 were basically conservative-evangelical in theology (with some fundamentalist areas), evangelistic, and mission-minded with a strong outreach program, well organized, engaged in many activities of practical and service character, with a vigorous denominational consciousness, a strong program of Christian education in the local congregations and in church colleges, high schools, and seminaries, manifesting a vital piety and sense of mission. The basic historic Anabaptist heritage had been preserved, although the effort to maintain a deep Christian commitment in full discipleship had not been uniformly successful, and the constant battle against worldliness was sometimes lost to looseness and sometimes to legalism.

By virtue of numbers, maintenance of historic heritage, vigor of group life, vitality, and strong participation of the lay membership in the total program of the church, the American Mennonites came to occupy a major place in world Mennonitism. Helped by their size and resources in men and money, and their growing sense of sharing in the life of the Mennonite brotherhood round the world, they were able to render valuable assistance to Mennonites elsewhere, especially in Europe where the suffering and losses due to two world wars have been much more severely felt. (For further information on American Mennonitism, see the articles on the several American bodies, also the several states in which American Mennonites live and treatments of major doctrinal, practical, ecclesiastical, and institutional topics.)

Baptized Membership of Mennonites in the United States by Bodies: 1957

| Mennonite Church | 70,884 |

| General Conference Mennonite Church | 35,315 |

| Old Order Amish Mennonite | 17,273 |

| Mennonite Brethren | 11,644 |

| Church of God in Christ, Mennonite | 4,389 |

| Old Order (Wisler) Mennonite | 4,140 |

| Beachy Amish Mennonite | 2,380 |

| Evangelical Mennonite | 2,269 |

| Evangelical Mennonite Brethren | 1,625 |

| Evangelical Mennonite (Kleine Gemeinde) | 25 |

| Krimmer Mennonite Brethren | 1,597 |

| Reformed Mennonite | 616 |

| Stauffer Mennonite | 362 |

| Weaver Mennonite | 60 |

| Total | 152,579 |

| Hutterian Brethren | 2,720 |

Source: Mennonite Yearbook and Directory (1958).

Bibliography

Bender, H. S. "The Mennonites of the United States." Mennonite Quarterly Review XI (1937): 68-82.

Bender, H. S. "Outside Influences on Mennonite Religious Thought." Proceedings of the Ninth Conference on Mennonite Educational and Cultural Problems (1953): 33-41.

Proceedings of the Conference on Mennonite Educational and Cultural Problems I-XI (1942-57).

Smith, C. Henry. The Coming of the Russian Mennonites . . . 1874-1884. Berne, 1927.

Smith, C. Henry. The Mennonite Immigration to Pennsylvania in the Eighteenth Century. Norristown, 1929.

Smith, C. Henry. Mennonites of America. Goshen, 1909.

Smith, C. Henry. Mennonites in America. Akron, 1942.

Smith, C. Henry. The Story of the Mennonites. Berne, 1941; 4th edition revised by Cornelius Krahn, 1957.

Smucker, Don. E. "A Critique of Mennonites at Mid-Century." Proceedings of the Ninth Conference on Mennonite Educational and Cultural Problems (1953): 99-113.

| Author(s) | Harold S Bender |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1959 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Bender, Harold S. "United States of America." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1959. Web. 3 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=United_States_of_America&oldid=78403.

APA style

Bender, Harold S. (1959). United States of America. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 3 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=United_States_of_America&oldid=78403.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 4, pp. 777-782. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.