Difference between revisions of "Amish Mennonites"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m |

m |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

__FORCETOC__ | __FORCETOC__ | ||

__TOC__ | __TOC__ | ||

| − | <h3>Introduction</h3> | + | <h3>Introduction</h3> |

| + | Amish Mennonites are that segment of the Swiss-Alsatian-South German Anabaptist-Mennonites and their descendants in [[North America|North America]] who are the offspring of the group who under the leadership of Elder [[Ammann, Jakob (17th/18th century) |Jakob Ammann,]] of Erlenbach, [[Bern (Switzerland)|canton of Bern]], [[Switzerland|Switzerland]], in 1693-1697 separated from the main body in Switzerland. | ||

Since the full story of this division is told in the [[Amish Division|Amish Division]] article, it remains only to say that Ammann must have visited the [[Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines (Alsace, France)|Markirch]] ([[Alsace (France)|Alsace]]) congregation about the same time, where he excommunicated some members, and that he almost immediately got into a controversy with the ministers of the [[p3594.html|Palatinate]] who tried to effect a reconciliation. He found almost united support from the ministers of Alsace, but proceeded to place most of the Palatine ministers under the [[Ban|ban]]. In a few years Ammann and his associates decided they had been too rash and tried to effect a reconciliation, failing largely because they confessed only to an error in method and spirit while refusing to surrender their demand for the <em>Meidung</em> ([[Avoidance (1953)|avoidance]] or shunning). Thus the division was made permanent because of the intransigence of Ammann. Ammann also held strict views on other points, including the wearing of the untrimmed beard, uniformity in [[Dress|dress]], including style of hats, garments for the body, shoes and stockings, and prohibition of attendance at services of the state church. He seems to have held that the <em>Treuherzigen </em>(those friends of the [[Anabaptism|Anabaptists]] who shared many of their views and helped them in times of persecution but for some reason would not join the group openly, perhaps out of fear) will not be saved, meaning that no one will be saved outside the Anabaptist fold. He also introduced footwashing as an ordinance, which was hitherto not practiced by the Swiss Anabaptists, but was practiced in Holland. | Since the full story of this division is told in the [[Amish Division|Amish Division]] article, it remains only to say that Ammann must have visited the [[Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines (Alsace, France)|Markirch]] ([[Alsace (France)|Alsace]]) congregation about the same time, where he excommunicated some members, and that he almost immediately got into a controversy with the ministers of the [[p3594.html|Palatinate]] who tried to effect a reconciliation. He found almost united support from the ministers of Alsace, but proceeded to place most of the Palatine ministers under the [[Ban|ban]]. In a few years Ammann and his associates decided they had been too rash and tried to effect a reconciliation, failing largely because they confessed only to an error in method and spirit while refusing to surrender their demand for the <em>Meidung</em> ([[Avoidance (1953)|avoidance]] or shunning). Thus the division was made permanent because of the intransigence of Ammann. Ammann also held strict views on other points, including the wearing of the untrimmed beard, uniformity in [[Dress|dress]], including style of hats, garments for the body, shoes and stockings, and prohibition of attendance at services of the state church. He seems to have held that the <em>Treuherzigen </em>(those friends of the [[Anabaptism|Anabaptists]] who shared many of their views and helped them in times of persecution but for some reason would not join the group openly, perhaps out of fear) will not be saved, meaning that no one will be saved outside the Anabaptist fold. He also introduced footwashing as an ordinance, which was hitherto not practiced by the Swiss Anabaptists, but was practiced in Holland. | ||

Revision as of 07:01, 4 October 2013

Introduction

Amish Mennonites are that segment of the Swiss-Alsatian-South German Anabaptist-Mennonites and their descendants in North America who are the offspring of the group who under the leadership of Elder Jakob Ammann, of Erlenbach, canton of Bern, Switzerland, in 1693-1697 separated from the main body in Switzerland.

Since the full story of this division is told in the Amish Division article, it remains only to say that Ammann must have visited the Markirch (Alsace) congregation about the same time, where he excommunicated some members, and that he almost immediately got into a controversy with the ministers of the Palatinate who tried to effect a reconciliation. He found almost united support from the ministers of Alsace, but proceeded to place most of the Palatine ministers under the ban. In a few years Ammann and his associates decided they had been too rash and tried to effect a reconciliation, failing largely because they confessed only to an error in method and spirit while refusing to surrender their demand for the Meidung (avoidance or shunning). Thus the division was made permanent because of the intransigence of Ammann. Ammann also held strict views on other points, including the wearing of the untrimmed beard, uniformity in dress, including style of hats, garments for the body, shoes and stockings, and prohibition of attendance at services of the state church. He seems to have held that the Treuherzigen (those friends of the Anabaptists who shared many of their views and helped them in times of persecution but for some reason would not join the group openly, perhaps out of fear) will not be saved, meaning that no one will be saved outside the Anabaptist fold. He also introduced footwashing as an ordinance, which was hitherto not practiced by the Swiss Anabaptists, but was practiced in Holland.

The proper name of the followers of Jakob Ammann is "Amish Mennonite" although frequently they are referred to simply Amish. Not all of the descendants have retained the name and the principles of the original group—none at all in Europe—most of them having reunited with the main body. However, there are still in the United States and in Canada those who retain the name in some form. In Europe there have been Amish settlements in Montbéliard, Holland, Bavaria, Galicia, and Volhynia, all of lesser size and significance, but in the United States many large and important Amish communities have been established. Because the Amish have kept few records, are highly traditional, and have produced practically no literature, not even historical, it is difficult to trace their history.

History in Europe

Switzerland

Originally there were two groups of Amish in Switzerland—(a) a few ministers and members in the Emmental; (b) all of the Anabaptists in the Lake Thun settlement. Very early (1696?) some of these emigrated to the Markirch area in Alsace, and soon after others went to the Neuchâtel (Jura) region of Switzerland. When the general emigration from the canton of Bern to the area of the Bishopric of Basel (Jura-Porrentruy) began, the Amish joined the movement establishing two congregations, La Chaux de Fonds and Neuenburg. By 1750 all the Amish were out of Bernese territory, although when the Bishopric of Basel was incorporated into Bern (1810?) the Amish congregations were still there. They gradually lost their distinctive identity and by the end of the 19th century were no longer considered Amish, being a part of the Swiss Mennonite Conference. A Swiss leader, probably Elder Samuel Baehler of Langnau, writing in 1886 in the Mennonitische Blätter (34-35) says: "I may add that there are also two so-called Amish Mennonite congregations here, one in the Neuchâtel Jura [La Chaux de Fonds] and the other in Basel [[[Basel-Holee (Basel Switzerland)|Holeestrasse]]]. As far as the Neuchâtel group is concerned they are quite closely related to us [the Swiss Mennonite churches], however they still practice footwashing among themselves." The Basel Amish congregation never associated with the Swiss Mennonite conference since it was actually a part of the Alsatian Amish group. Few Amish emigrants came directly from Switzerland to the United States.

Alsace-France

When the Amish division occurred there were several Anabaptist-Mennonite congregations in Alsace (at that time not a part of France). All of these followed Ammann's lead and Ammann himself settled in Ste-Marie-aux-Mines (Markirch) in 1696. When heavy pressure and actual persecution forced emigration from this area (1710-1730), a considerable number of families migrated to the territory of Montbéliard (in German, Mümpelgart), at that time and until its incorporation into France in 1790(?) an enclave belonging to the Protestant duchy of Württemberg in South Germany. Others settled in the region of Birkenhof on the Alsatian-Swiss border. Under pressure some of the Ste-Marie-aux-Mines group moved across the nearby border into Lorraine. Gradually Amish families migrated to other places until small congregations had been established well into the interior of France proper, and by 1815, a small settlement in Luxembourg. Emigration also took Alsatian Amish families eastward and northward into Germany and after 1815 to North America. Small groups were settled by 1759 in southern Baden across the Rhine in the Breisgau and by 1802 in Southern Bavaria near Ingolstadt, Regensburg, and Munich. Direct emigration from Alsace-Lorraine and Bavaria to the United States and Canada resulted in large Amish communities: in Waterloo County, Ontario (1824 ff.), Central Illinois (1829 ff.), Stark County, Ohio (Canton), and Fulton County, Ohio (Archbold, 1835 ff.). A heavy drain from the Alsace-Lorraine-Montbéliard Amish communities to these North Central states took care of excess population and kept down their further expansion in France. A continuous small trickle of Swiss Mennonite families into southern Alsace from 1880 on gradually diluted the Amish stock, especially around Mulhouse and Altkirch. About 1790 a small number of Montbéliard (and Ibersheim, Germany) Amish families migrated to the Lemberg region in Galicia and from there to Volhynia, Russia, whence they reached Kansas and South Dakota as a part of the great Russian emigration in 1873 ff.

Germany

Of the Swiss Mennonites living in the Palatinate at the time of the Amish schism only a small number followed Ammann, chiefly in the region of Kaiserslautern. Later a settlement from Alsace was made at Essingen near Landau. The Amish did not expand in the Palatinate but did send out emigrants in three directions (largely supplemented by families from Alsace and Lorraine). The first of these was to middle Germany in the Hesse-Cassel region, where as early as 1730 certain families appeared in Wittgenstein, then Waldeck (by 1750), then in the Lahn Valley near Marburg (by 1800). A small settlement also existed for a time near Neuwied and also in the Eiffel region. By 1830 these groups began to disintegrate by direct emigration to the Amish settlement in Somerset County, Pennsylvania, Garrett County, Maryland (region of Grantsville-Springs), and to the Amish settlement in western Waterloo County, Ontario. An Amish settlement in Hesse north of Wiesbaden sent large numbers of settlers to Butler County, Ohio, 1817ff. These are known as the Hessian Amish. All the European Hessian Amish congregations died out by 1900. The second Amish movement from the Palatinate (and from Alsace-Lorraine) was to Bavaria (Ingolstadt, Regensburg, and Munich). The Ingolstadt and Munich groups ultimately became extinct by emigration (to Ontario and Illinois). The Regensburg group continued, however, diluted with Mennonite additions from other places in South Germany, and the Munich congregation was reconstituted with a mixed Amish and Mennonite population from other places. The third emigration was to Galicia and Volhynia 1785 ff. This group emigrated in toto to the United States in the great Russian emigration of 1873 ff., settling at two places, viz: Moundridge, Kansas, and Freeman, South Dakota. Meanwhile the remnants of the original Palatinate Amish settlements merged with the Mennonite congregation of Kaiserslautern in 1915.

Russia

The only Amish settlement was that in Volhynia, made by families who had at first settled near Lemberg in Galicia, founded in 1803, becoming extinct by migration to the United States in 1875.

Holland

Two Amish congregations were established near Groningen and Kampen by immigration from Switzerland and the Palatinate about 1750. They continued a separate existence there until about 1850 when they were absorbed into the Dutch Mennonite congregations nearby.

Amish Conferences and Literature in Europe

Two Amish general conferences are known to have been called for the purpose of giving guidance in church policies and discipline, with formulated resolutions which have been handed down in manuscript form: at Essingen near Landau, Palatinate (at that time Alsace) in 1759, and at Essingen again in 1779. The Amish churches used the Dordrecht Confession of Faith (1632, adopted by the Alsatian churches in 1659) together with the Elbing catechism of 1783, reprinted at Waldeck in 1797 and henceforth known as the Waldeck Catechism. They also adopted the Ernsthafte Christenpflicht (1739) as their prayerbook and reprinted the Ephrata German Martyrs' Mirror at Pirmasens in 1780. No permanent conference of distinctively Amish churches in Europe was ever organized, although after the incorporation of Alsace-Lorraine in Germany in 1870 the churches there affiliated loosely with the Badische Verband and organized their own separate conferences in 1901 and 1907. After the reincorporation with France in 1918 two separate conferences were formed, a French-speaking and an Alsatian German-speaking, both of which continue. Distinctive Amish practices and customs persisted until into the 20th century but gradually died out—wearing of the full beard, hooks and eyes and special costume, shunning and footwashing. Two congregations alone, Birkenhof and Diesen, still retain the practice of feetwashing. The Luxembourg group retained this practice until 1941 when their aged bishop died. Thus any distinctive contribution of the Amish to European Mennonitism was lost, and the effects of the schism of 1693 were completely overcome by attrition without any conscious formal reunion. The churches at Regensburg and Munich, it is true, never joined the Mennonite conference of this region, known as the Badische Verband, although this was due more to personalities than to principles except that these churches do not desire to submerge their autonomy into the rather close corporate government of the Badische Verband. They have however joined both the South German Mennonite Conference (formed in 1886) and the all-German Vereinigung (in 1908).

North America

Pennsylvania

The first scattered Amish settlers arrived in Pennsylvania possibly as early as 1720, and not being able to fellowship with the Mennonites already there, settled in Berks and Chester counties adjoining the Lancaster County settlement in the east, as well as in Lancaster County proper, forming three congregations about 1740-1760: one north of Reading which became extinct by 1786 as the result of Indian raids, one in Chester County near Malvern, which died out before 1800, and one near Morgantown which soon developed into a very large settlement and spilled over into Chester County, ultimately extending over a block of 40 miles north and south and 20 miles east and west, which in 1950 contained at least 4,000 baptized descendants of the pre-Revolutionary settlers. This group always remained sharply distinct from the larger Lancaster Mennonite Conference group with which it was in the closest geographical proximity. Because of lack of land, all later Amish immigrants passed by this region, except for transient halts, and the surplus population also migrated westward. Direct settlements were established from the Berks-Lancaster-Chester settlement only in Somerset County (1767 ff.), Mifflin County (Kishacoquillas Valley) 1793 ff., and Union County, Pennsylvania (Buffalo Valley) 1810, extinct by 1890, and in Fairfield County, Ohio, 1810 ff., extinct by 1890 also. A few scattered families continued to go west during the next century, but not until 1940 was a true daughter colony established, and then only on a small scale in St. Mary's County, Maryland. The Somerset County settlement was actually populated more by direct immigration from Hesse 1830-1860 than from Eastern Pennsylvania, spilling over into adjacent Garrett County, Maryland. The Somerset County group was in three distinct locations, north around Johnstown, middle around Berlin, and south around Springs-Grantsville. Only the south settlement survived the 19th century.

Ohio

The chief daughter colony of the Somerset County settlements was the large Holmes County, Ohio, colony, begun in 1807, but not flourishing until after the War of 1812, although some Somerset County families moved directly to the Johnson County, Iowa, settlement 1845 ff. and to Elkhart County, Indiana, about the same time. Yet both these latter settlements were predominantly offshoots of the Holmes County settlements. This Holmes County group gradually expanded into Tuscarawas County eastward and into Wayne County northward, ultimately becoming the largest single settlement of Amish, exceeding even the Berks-Lancaster settlement, with a baptized population of about 5,000 in 1990. Daughter settlements from Holmes County are Geauga County (1880), Stark County (Hartville), and Plain City, Ohio, and Arthur, Illinois. (1880).

The Fairfield County Amish settlement disintegrated when some families moved to Wayne County, near Smithville, and to the West Liberty, Ohio, settlement, and later largely to Lagrange County, Indiana, near Topeka and Ligonier. However, the Smithville and West Liberty settlements were actually founded directly from Mifflin County and Union County, Pennsylvania (with some Lancaster-Berks additions), in 1810 and 1845 respectively. Daughter colonies from these latter two settlements were those of Cass County (Garden City), Missouri. (1880) and Hubbard, Oregon. (1890).

Direct Alsatian Amish settlements were made in Stark County (near Louisville) 1830, Wayne County 1830 ff., and Fulton County, Ohio, 1835 ff. (the latter with a large element from Montbéliard). Some emigration from these settlements helped establish the Washington-Henry County, Iowa, colony near Wayland (1847) and the Allen County, Ind. (Leo-Grabill) and Adams County, Indiana (Berne), both about the same time, although direct immigration from Alsace to both contributed. There was cross-immigration also from the Amish settlement in Ontario to these settlements.

New York

A single Amish settlement was established in New York State direct from Alsace and Bavaria in 1845 in Lewis County (Croghan) with cross-migration from the Ontario Amish settlement.

Indiana

There was no substantial original direct Amish immigration from Europe to Indiana. The Allen County-Adams County Alsatian type settlement of 1850 have been mentioned. In Elkhart County immigrants direct from Somerset County, Pennsylvania, established the largest Amish settlement west of Holmes County (with additions from this latter place) in 1842, east of Goshen, and slightly later around Nappanee west of Goshen. Today these two settlements together (not geographically one) have a baptized population of at least 4,000. The Howard-Miami settlement (north of Kokomo) 1860 and the Daviess County colony southwest of Indianapolis, were both established from Holmes County and never became large.

Illinois

A large Alsatian Amish settlement was established 1829 ff. in Central Illinois east of Peoria with later outposts at Hopedale, Flanagan, Tiskilwa (the latter chiefly from Bavaria), and Fisher. A small Lancaster-Mifflin County Amish colony was established near Danvers in 1854.

Iowa

The Iowa Amish came in two groups about the same time (1845) settling in two distinct colonies: the Alsatian Amish in Henry-Washington County, near Wayland (with additions from Ontario), and the Holmes County-Somerset County group near Kalona (Johnson County).

Nebraska

Nebraska received a considerable Alsatian Amish settlement near Milford, largely by way of the Central Illinois, Wayland, Iowa, and Ontario settlements. A daughter settlement was established at Tofield, Alberta, north of Edmonton about 1910. Another settlement was established at Albany, Oregon, by way of Thurman, Colorado, in 1894.

Kansas

In 1888-1890 Harper County received an Amish migration of the Somerset-Holmes County strain, with some additional contingents from Elkhart County, Indiana, Arthur, Illinois, and Johnson County, Iowa. Earlier in 1875 the Volhynian Amish had come to Moundridge but with connections only with the Russian Mennonites, not with the older American Amish.

South Dakota

The Volhynian Amish group settled near Freeman in 1875.

Ontario

The large Amish settlement in Waterloo County west of Kitchener was established in 1824 ff. by Amish from Bavaria and Alsace-Lorraine. A small outpost of this group was established near Zurich, some 90 miles farther northwest.

Summary

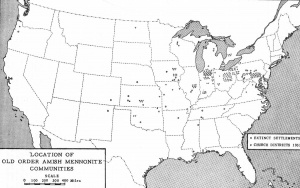

Thus, in 150 years a large number of Amish settlements were gradually scattered across the United States from Eastern Pennsylvania to Oregon, as well as into Canada. These consisted of three major strains: the earliest 18th century immigration from Switzerland and the Palatinate to Eastern Pennsylvania, the 19th century Alsatian-Bavarian-Hessian Amish movement to western Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, and Ontario, and the Volhynian Amish of the 1874 immigration to Kansas and South Dakota.

Of these three the last group had almost lost its Amish character before it came and soon was assimilated almost completely into the Western and Northern District General Conference groups. The Alsatian-Bavarian Amish ultimately all were assimilated into the (Old) Mennonite Church (MC) group, with a few exceptions which have broken off in a conservative reaction to remain outside the main stream. The Lancaster-Mifflin-Somerset segment, the first migration with its daughter colonies, has broken up into four phases: (1) the largest which remained strongly in the original (old) Amish pattern, independent, non-assimilated; (2) a medium-sized progressive phase which was assimilated into the (old) Mennonite group along with the Alsatian Amish; (3) and another group of about the same size which held the middle of the road, remained independent but organized into the Conservative Amish; (4) a still more progressive phase, which in turn was broken up into two sub-phases, the Central Illinois (Stucky) Amish group now merged with the General Conference, and the smaller (Egli Amish or Defenceless) Evangelical Mennonite group, an independent organized conference.

Amish Names

A large number of the family names among the Amish are unique and characteristic of that group although, since before 1693-1697 Swiss and Alsatians were a united group, some family names will be found in the descendants of both groups today. The following list includes all the more numerous and characteristic Amish family names.

Amish family names primarily of the Old Order and Conservative Amish groups and those descending from the early Pennsylvania Amish settlers and the Hessian Amish:

| Beachy-Peachey | Bender | Blauch-Blough | Bontrager-Borntraeger | Brenneman |

| Byler-Beiler | Burkholder | Christner | Chupp | Coblentz |

| Esch-Eash | Gingerich-Guengerich | Glick | Graber | Hartzler-Hertzler |

| Helmuth | Hershberger | Hooley | Hostetler-Hochstetler | Kanagy-Gnaegi |

| Kauffman | Keim | King | Knepp | Lambright |

| Lantz | Lapp | Mast | Miller | Mullet |

| Nissley | Otto | Petersheim | Plank | Raber* |

| Schrock | Shetler | Slabaugh-Schlappach | Smucker-Schmucker | Stoltzfus |

| Stutzman | Swartzendruber-Schwarzentruber | Troyer | Umble | Wagler* |

| Yoder | Zook-Zug | |||

| *More common in the Alsatian group. | ||||

Amish family names primarily of the Alsatian group and their descendants:

| Albrecht | Augsburger | Bachman | Bechler | Beller | Belsley | Berkey-Burcki |

| Camp-Kemp | Conrad | Egli | Oesch-Esch | Eicher | Fahrney | Flickinger |

| Gascho | Gerig | Gunden-Gundy | Guth | Heiser | Imhoff | Jantzi |

| Kennel | Kinsinger | Klopfenstein | Litwiller | Nafziger-Noffsinger | Oyer-Auer | Raber |

| Ramseyer | Rediger | Ringenberg | Rocke-Roggi | Ropp-Rupp | Roth | Ruvenacht |

| Schertz | Slagel | Smith | Sommer | Springer | Stahley | Strubhar |

| Stuckey | Studer | Sutter | Sweitzer | Verkler | Wagler | Wyse |

| Yordy | Yutzi-Jutzi | Zehr |

Schisms

The Amish communities which were settled in America before 1870 experienced a number of serious schisms which broke the unity of the group. Even apart from this, the earlier pre-Revolutionary immigrants of the Berks-Lancaster settlement and the latter Alsatian Amish immigrants never really formed a harmonious working relationship although the Amish General conferences 1862-78, called Diener-Versammlungen, represented a partially successful attempt. The following schisms and resultant branches are to be noted:

- Old Order versus Progressive 1850-1880. The Old Order Amish group resisted change and has continued to this day as unorganized but close-knit group settlements with communion fellowship of about 14,000 baptized members. The progressive element organized three district conferences after 1882: Eastern Amish Mennonite, Indiana-Michigan Amish Mennonite, and Western District Amish Mennonite, all of which later merged with the Mennonite Church (MC) conferences and are now an integral part of that branch.

- An in-between group of congregations which did not accept either the Old Order or the progressive position organized the Conservative Amish Mennonite Conference (which later dropped the name Amish) in 1910, which with allied independent congregations numbers about 4,000 members. In the mid-20th century, over 20 congregations with nearly 1,500 members, standing between the Old Order and the Conservative Amish, have been formed from groups breaking away from the Old Order.

- On the other hand, two schisms occurred among the Alsatian Amish settlements of Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio 1865-1875 which led to the formation of the Evangelical Mennonite Church (at first called Defenceless Mennonites), with about 1,500 members, and the Central Conference (Illinois) later a member of the General Conference Mennonite Church, with some 3,000 members. In the Defenceless group about 1898 a schism resulted in the formation of the Missionary Church Association with over 5,000 members. The Volhynian Amish settlements of Freeman, South Dakota and Moundridge, Kansas never formed a separate conference but joined the General Conference Mennonite Church as individual congregations.

The characteristic practices, customs, and attitudes known as "Amish" are actually characteristic only of the Old Order Amish today.

See also Old Order Amish for an earlier more detailed description of the Old Order Amish written in the 1950s by John A. Hostetler. See Amish for a description of the Old Order Amish in the second half of the 20th century. See Amish Division for a description of the origins of the Amish.

Bibliography

Hostetler, John A. Annotated Bibliography on the Amish. Scottdale, 1951, an exhaustive bibliography of publications in North America by or about the Amish of all groups.

Additional Information

| Author(s) | Harold S Bender |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1953 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Bender, Harold S. "Amish Mennonites." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1953. Web. 3 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Amish_Mennonites&oldid=102028.

APA style

Bender, Harold S. (1953). Amish Mennonites. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 3 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Amish_Mennonites&oldid=102028.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, pp. 93-98. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.