Manitoba (Canada)

1957 Article

Introduction

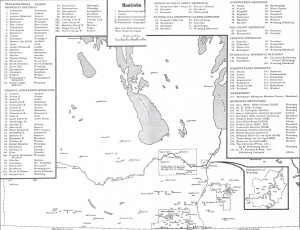

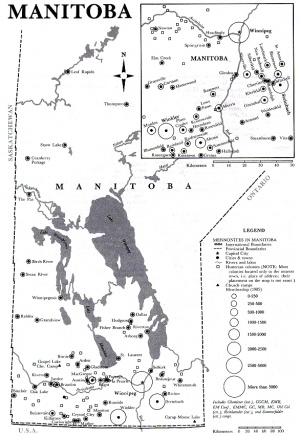

Manitoba, a province of central Canada, area 647,797 km2 (250,116 sq mi), population in 1951 of 729,744 (1,207,959 in 2008), with 44,667 Mennonites in that year, divided into 16 civil units, called municipalities, bounded on the south by Minnesota and North Dakota, on the west by Saskatchewan, and the east by Ontario; chiefly an agricultural province, wheat being the main crop. Winnipeg is the capital. Its many lakes and rivers drain to Hudson Bay. The principal rivers are the Red, the Winnipeg, and the Saskatchewan. The Red River settlement was established by Selkirk in 1811 and was the nucleus of the province when it was organized in 1870. Beginning in 1874 Mennonites from Russia settled in Manitoba on both the east and west of the Red River between Winnipeg and the United States boundary. This area in 1958 still constituted the main concentration of Mennonites in the province. The great change that has taken place is that whereas they were originally confined to the rural areas, they are found in the 1950s in all the surrounding towns and cities and particularly in Winnipeg, which had 5,751 baptized Mennonites in 1951, and over 7,000 in 1955.

The Coming of the Mennonites

The Mennonites of Manitoba were of Prusso-Russian background; they began to come to Manitoba in the 1870s as a result of the introduction of universal military conscription in Russia. The second and third waves of Mennonite immigrants came to Manitoba after World Wars I and II. By far the largest of these three was the second migration, when nearly 21,000 Mennonites came to Canada. In contrast with the immigrants settling in the prairie states of the United States in 1874-1880, who were primarily from the Molotschna settlement of Russia, Prussia, and Poland, the Manitoba settlers of the same period were with a few exceptions from the Chortitza or Old Colony settlement and its daughter settlements Bergthal and Fürstenland. That this group and some of the Kleine Gemeinde Mennonites chose Manitoba was not accidental. The delegates of these groups were interested in the most liberal guarantees which would safeguard the future of their traditional economic, cultural, and religious life in a foreign environment as they had known it in Russia. Most of the Mennonites settling in the United States, particularly those of Molotschna and Prussia, were willing to adjust themselves to a much greater degree to the environment of the chosen land. They had already adjusted themselves to the economic and cultural life of their Prusso-Russian homelands to a larger degree than the conservative Old Colony groups.

After delegates from the Chortitza and Molotschna settlements had repeatedly tried in vain to obtain from the Russian government a guarantee to the effect that they would continue to be exempt from any form of governmental service to the country some of the leaders listened to voices stating that the only alternative would be emigration to a country which would offer them the "Privilegium" which the Russian government had given them and was now withdrawing. Cornelius Jansen and Leonhard Sudermann promoted this idea. Many meetings took place in the Chortitza and Molotschna settlements. The Bergthal and Fürstenland Mennonites took an active part in these meetings and watched the development with apprehension. Under the influence of Cornelius Jansen, Elder Gerhard Wiebe of Bergthal became interested in emigration to North America. When a delegation of 12 was sent to North America in 1873 to investigate settlement possibilities, the Bergthal group sent Jacob Peters and Heinrich Wiebe. The Old Colony (Chortitza) itself and Fürstenland had no official representatives in the delegation. The Kleine Gemeinde was represented by David Klassen and Cornelius Toews. Meanwhile John Lowe, Secretary of the Canadian Department of Agriculture, sent William Hespeler to Russia, who met Cornelius Jansen at Berdyansk on 25 July 1872, and promised the Mennonites "fullest assurance as to freedom from military service."

The Bergthal delegates, Peters and Wiebe, arrived in Berlin, Ontario in March 1873, where they were guests of Jacob Y. Shantz, who was a great booster of Manitoba. Together they investigated Kansas, Texas, Colorado, and Nebraska, finally proceeding to the Red River Valley of Manitoba to meet the other delegates. Here the 12 delegates were introduced to the governor by Hespeler. A group of 24 persons on five wagons drove 40 miles southeast of Winnipeg to inspect the land which became known as East Reserve. Before the group had seen all the eight townships of the East Reserve they returned to Winnipeg; most of them, being disappointed, went to the United States. Hespeler accompanied the four Bergthal and the Kleine Gemeinde delegates to the West Reserve located north of the boundary and west of the Red River extending toward the Pembina Mountains.

After this inspection four of the delegates proceeded to Ottawa, where they received on 26 July 1873 a statement regarding the conditions under which the Canadian government would accept and settle the Mennonites who desired to come to Manitoba. These "privileges" were briefly the following: (1) complete exemption from military service; (2) a free grant of land in Manitoba; (3) the right to conduct their own traditional schools (with German and Bible as the main subjects); (4) the privilege of affirming instead of taking the oath in court; (5) a cash grant for passage from Hamburg to Ft. Garry (Winnipeg) of $30 per adult, $15 per child under eight years, and $3 per infant.

After the return of the delegation to Russia the Bergthal group, consisting of five villages, went in a body to the East Reserve of Manitoba. Elder Gerhard Wiebe reported about the choice as follows: "The congregation chose Canada because it is under the protection of the Queen of England and, therefore, we believe that the principle of nonresistance will be maintained there for a longer period of time and also that the school and the church will be under our own administration." The last point was made possible because the Canadian government set aside the East Reserve and West Reserve tracts for the Mennonites to establish compact settlements with their own schools and local administration. Although the Mennonites probably misunderstood the extent and duration of some of these "privileges," the United States could not match this offer.

The first Bergthal immigrants arrived in Winnipeg on 31 July 1874 on the steamer International by way of Chicago, St. Paul, and the Red River. Immigrant houses had been erected for them at the place where Niverville is located today. During 1874, 780 Bergthal Mennonites arrived, who were joined by members of the Kleine Gemeinde. The largest number of Bergthal immigrants came in 1875, followed by the last group in 1876, making a total of about 500 families consisting of nearly 3,000 persons who were transplanted from Bergthal in Russia to the East Reserve in Manitoba.

The Kleine Gemeinde also came to America as a group, being the conservative wing of the Molotschna Mennonites, organized by Klaas Reimer. About half of the members of the group went to Jansen, Nebraska, and the other half to Manitoba, where they established Steinbach on the East Reserve and Rosenhof and Rosenort on the West Reserve. The total number of this group that went to Manitoba was about 800 persons. They were the only Molotschna Mennonites to settle in Manitoba.

In 1877 the East Reserve consisted of 38 villages occupied by 700 families with some 3,500 people. The majority had come from Bergthal and had been joined by a few families from the Chortitza settlement and the small Kleine Gemeinde group. Some of the original 38 villages still in existence in the 1950s were Steinbach, Grünthal, Chortitz, and Schönsee. The villages were patterned after those which the Mennonites had left in Russia and received the same names. The advisers and sponsors of the settlements on the East Reserve were William Hespeler of the Department of Agriculture and the Ontario Mennonite Jacob Y. Shantz. When Lord Dufferin visited the East Reserve on 21 August 1877, he praised very highly the progress made by the settlers. In Winnipeg he reported that he had seen "village after village, homestead after homestead, furnished with all conveniences and incidents of European comfort," and he had seen "cornfields already ripe for harvest and pasture populated with herds of cattle stretching away to the horizon." The Canadian government loaned the Mennonite immigrants nearly $100,000, guaranteed by the Mennonite Aid Committee of Ontario, to which the latter added some of its own funds.

Apparently the Bergthal Mennonites reserved for themselves the East Reserve, leaving the West Reserve for the Mennonites from the Old Colony and Fürstenland. Fürstenland, the daughter colony of Chortitza, had its own elder in Johann Wiebe, but did not have its own Oberschulze. Administratively it was a part of the Chortitza settlement, at the time of migration. The leadership of the Chortitza or Old Colony settlement was more progressive. Elder Gerhard Dyck and his co-minister Heinrich Epp of Chortitza had been in St. Petersburg repeatedly but they did not favor emigration to America. Elder Gerhard Dyck and Elder Johann Wiebe of Fürstenland, and Elder Gerhard Wiebe of Bergthal, were related and in contact with each other. In spite of the fact that the Chortitza settlement had no intellectual leaders and delegates as promoters of the emigration, a great number of the Mennonites from this settlement were ready to go to Canada. They attached themselves to the spiritual leadership of Johann Wiebe of Fürstenland. Some 300 families or 1,600 persons settled on the West Reserve in Manitoba during 1875. The West Reserve, consisting of 17 townships comprising an area of 612 square miles, was located west of the National border between the Red River and the Pembina Mountains, and reaching to the United States border. During the summer of 1875 the first arrivals were living in immigration houses while villages were laid out and homes constructed.

Jacob Y. Shantz, who kept a list of all Mennonites passing through Ontario on their way to Manitoba (this list has been preserved in the Mennonite Library and Archives, Bethel College (North Newton, Kansas, USA)), reported that 258 families came to Manitoba in 1874, and 621 families the following year, making a total of 879 families or some 5,000 persons. The total number of immigrants to Manitoba from 1874 to 1880 was (according to Shantz) 7,442 persons. D. H. Epp {Die Chortitzer Mennoniten) reported that 3,240 of them came from the Chortitza and Fürstenland settlements. Shantz listed a total of 799 persons from the Kleine Gemeinde. Adding these two lists totals 4,039, which leaves 3,403 as coming from the Bergthal settlement. The question left open is how many of the total of 3,240 listed by Epp came from Fürstenland and how many from Chortitza. E. K. Francis (In Search of Utopia, 89), who thought that all the Mennonites of the West Reserve came from Fürstenland, and for this reason refers to the Old Colony Mennonites of the West Reserve as "Fürstenlander," evidently overlooked Johann Wiebe's statement that 1,009 persons were ready to leave Fürstenland, and also Epp's report that a total of 3,240 went to Manitoba from Chortitza and Fürstenland. Fürstenland had 154 farms. On the assumption that there were 154 families consisting of 7 members each the total was 1,078. This would mean that nearly the total population was included in Johann Wiebe's figure of 1,009, and that it was impossible that all 3,290 had come from Fürstenland. We can thus conclude that the Bergthal group was slightly larger than the Chortitza-Fürstenland group together, and that of the Chortitza-Fürstenland group about one third came from Fürstenland, while the other two thirds came from Chortitza, The term "Old Colony" Mennonites referring to the conservative group of the West Reserve was therefore appropriate.

By 1877, 25 villages had been established on the West Reserve. Most of the names were repetitions of those in use in the Chortitza or Old Colony settlement in Russia: Rosengart, Neuendorf, Blumengart, Kronsthal, Chortitza, Osterwick, Schönwiese, etc. In the two reserves together some 110 villages were established in the first decade. Some gradually disintegrated, others were transplanted to other localities. When the East and West Reserves were finally set aside "for the exclusive use of the Mennonites from Russia" by Order-in-Council of 25 April 1876 they included 25 townships or over a half million acres, which was about 6 per cent of the total area of Manitoba at that time (Francis, 62).

Adjustment to the New Environment

The Chortitza-Fürstenland people had scarcely all arrived when a shift of the Bergthal people from the East Reserve to the West Reserve set in. Around 1880 Hespeler reported that some 300 families of the East Reserve had moved to the West Reserve, leaving 400 families in the East Reserve. The reason he gave for this was that the East Reserve suffered more during the wet years since it lay lower than the West Reserve. Also, the Dominion Lands Acts made it possible for those in the East Reserve to acquire a second homestead in the West Reserve. Some of the villages established by the Bergthal people on the West Reserve were Gnadenfeld, Schönhorst, Sommerfeld, Halbstadt, Altonau, Bergfeld, and Schönthal. Already at this time departure from the traditional village settlement pattern was becoming common among the Bergthal people; a similar departure soon became apparent in other areas of life. Thus the Bergthal Mennonites of the East Reserve introduced a disrupting element into the fixed pattern of the Old Colony Mennonites of the West Reserve. Innovations introduced by Bergthal Mennonites were, however, as a rule followed and accepted by some of the Old Colony Mennonites.

The Bergthal Mennonites of the East Reserve continued as an ecclesiastical unit under the name Bergthal Mennonite Church, while the Chortitza-Fürstenland group on the West Reserve was organized as the Reinland Mennonite Church (named after Reinland municipality), which later became known as the Old Colony Mennonite Church. They had all come from the same background, but had developed slight differences which increased from year to year. Now that the large group of the Bergthal Mennonites had moved into the heart of the Old Colony Mennonite settlement the differences were accentuated by innovations and personality clashes. The Chortitza-Fürstenland group of the West Reserve became the custodian of tradition, while the newcomers from the East Reserve, the Bergthal Mennonites, became champions of progress and adjustment to the new environment. For the Old Colony Mennonites of the West Reserve the village pattern was the only way of life permissible and deviation was punishable. There was also disagreement regarding singing and the use of songbooks. Thus the Bergthal Mennonites from the East Reserve who had located in the West Reserve could not worship and have fellowship with the Old Colony group of the West Reserve. After 1880 they had had their own elder in Johann Funk. Elder Johann Wiebe of the Reinland or Old Colony Mennonite Church of the West Reserve called a Bruderschaft (general meeting of male members) on 5 October 1880, at which it was decided that those who were willing to adhere to the traditional principles and practices of the church should renew their membership, thus eliminating those who were lukewarm. The "lukewarm" members actually preferred to join the Bergthal Church of the West Reserve and did so. Thus the differences between Old Colony and Bergthal Mennonite groups were in various respects intensified.

In 1880 the provincial government intended to replace the Mennonite self-government of the Schulze and Oberschulze as based on old practices in Russia by the regular Canadian civic government. In the East Reserve the change met little opposition. The Bergthal Mennonites of the West Reserve were also ready to accept this change, particularly since the Mennonite government was in the hands of the previously established Old Colony Mennonite authority. For the Old Colony Mennonites to give up their self-government with the Schulze and Oberschulze and to yield to the Canadian municipality system meant not only forfeiting a practical and cherished tradition, but also the infiltration of practices and directives coming from a government beyond the jurisdiction of the elders and the discipline of the congregation. In spite of this opposition the municipality of Reinland was organized in 1883. The civic offices were usually filled by members of the Bergthal Church or by those expelled from the Old Colony Church. The Old Colony Mennonites approved of the Waisenamt (a mutual aid system centering around the care of orphans), but refused to cooperate in the Brandordnung (a mutual fire insurance) of the Bergthal Mennonites. Excommunication and the ban were used for those who adjusted themselves by wearing the clothing of the Canadian environment and by introducing other innovations such as bicycles.

One of the greatest problems arose from the school question. The Old Colony Mennonites of the West Reserve wanted to have their own teachers (without special preparation) teaching the children during a short term for a few years according to their own curriculum. The Kleine Gemeinde and the Bergthal Mennonites were more progressive and willing to avail themselves of government aid to improve teaching, and in a number of Mennonite villages established district schools. The first inspector of the Mennonite district schools was Jacob Friesen. H. H. Ewert, principal of the Gretna Mennonite School, did much to improve the educational system and practices of his day, particularly after he was appointed government inspector. This only antagonized the conservative Old Colony element. (The problems regarding the school question are discussed in detail in the article Old Colony Mennonites.

Economic Life

By 1907 the West Reserve was encircled by a network of railroads, supplied with grain elevators and business places. Winnipeg became an accessible market for butter, cheese, cream, poultry, eggs, and livestock. The tendency to abandon the traditional village and to settle on one's own land increased after 1880. First it was noticeable in the outskirts of the Reserve from Winkler south to the international boundary and from there east to Gretna. By 1898 the West Reserve had only 24 villages left. This involved changes regarding the traditional community land which had to be parceled out to those who left the village. Three-year rotation of crops gradually gave way to the Canadian practices. Great changes came about through the purchase of modern American machinery. The Mennonites were credited with the introduction of the mulberry tree, flax, and sunflowers to Manitoba. Until the turn of the century the Mennonites of Manitoba and Ontario had a kind of monopoly on Canada's flax production. Grain was brought along in bags by the immigrants, especially wheat. But this hard winter wheat, which had made Kansas famous, proved to be a failure in Manitoba. Spring wheat, oats, and barley became staple crops. Vegetables and fruits were cultivated. Jacob Y. Shantz helped the Mennonites along these lines. Mennonites made use of milling facilities wherever they were provided commercially by outsiders, and built their own mills only when such services were not available. Windmills were located in a number of villages. Feed mills were found in Blumenort, Altona, and Gretna. Steinbach of the East Reserve also had its own mills. Cheese making became important among the Mennonites, who generally operated on a cooperative basis. The early Mennonite cheese factory disappeared when milk and cream could be sent to the market in Winnipeg.

On the favorable soil of the West Reserve wheat and cash crop farming soon became prevalent, while most of the East Reserve with its inferior soil was for many decades limited to dairy farming. A middle-sized farm was 100 acres. In the East Reserve the tendency was to increase the size. The West Reserve soon began to suffer from overpopulation, partly because the young people were kept close to home, until an opportunity to found daughter colonies arose. Because of the rapid increase of the Mennonite population it became necessary to subdivide standard-size homesteads. This was handled through the Waisenamt. The Mennonites had not immediately occupied all the land of the two reserves. Later the ban against non-Mennonite settlers was lifted and non-Mennonite population moved into the unoccupied areas of the reserves. On the other hand the Mennonites later extended their own landholdings in other directions beyond the limits of the reserves. The Old Colony Mennonites took the initiative in creating a new reserve in the Rosthern-Hague district of Saskatchewan, where by 1897, 200 Mennonite families from Manitoba were residing in villages just as they had been in Manitoba. Another settlement was made in Swift Current, Saskatchewan, in 1904, also by the Old Colony Mennonites. Other settlements were established in Didsbury, Alberta, Drake, Saskatchewan, and other places. According to the church record of the Old Colony Mennonite Church (J. P. Wall) the total number of Old Colony Mennonites in Canada in 1912 was 8,166 souls, of whom 4,358 lived in Saskatchewan. This showed that more than half of the Old Colony Mennonites were at that time located in Saskatchewan. In 1911 the number of the Mennonites in Manitoba was 14,498 (according to the census given by Dawson) and for Saskatchewan 6,542, which makes a total of 21,040. The Old Colony group was thus about 40 per cent of the entire Mennonite population.

Religious Life

The religious and cultural life of the Manitoba Mennonites was marked by very conservative attitudes. With the exception of the small Kleine Gemeinde group, they were all of the same Old Colony background. The Bergthal group had been established as a daughter colony only a few decades earlier in Russia. The Fürstenland daughter settlement had been established only about ten years before the departure to Canada. Although it furnished in Johann Wiebe the elder for the West Reserve, it was only a small segment of the total. The real differences in religious and cultural views originated in Canada and were possibly to a large extent due to personalities. The immigrants coming from the Bergthal settlement in Russia settled under the leadership of Gerhard Wiebe on the East Reserve. This was the nucleus for the Bergthal Mennonite Church. The Old Colony or Chortitza and Fürstenland Mennonites settled on the West Reserve, establishing the Reinland Mennonite Church, better known since as the Old Colony Mennonites, under the leadership of Elder Johann Wiebe from Furstenland. These two groups were apparently getting along well with each other. Through the infiltration of the Bergthal element on the West Reserve differences and difficulties arose, most of them relating to the retention of the religious and socioeconomic practices of the old country or sacrificing them for new practices of the Canadian environment. The question arose whether a member of the church could withdraw from the village and settle on his quarter of land, and exchange furniture, implements, clothing, etc., which he had brought along, for those in use in Manitoba. Of great significance was the matter of accepting government-sponsored schools and government administration of the settlements. Gradually, however, the Schulze and Oberschulze were replaced by the reeve, and Mennonite church schools by district schools. All this was alarming for the Mennonites, who remembered that they had come to Manitoba not only because of their objection to a government-prescribed service but also out of opposition to the Russianization program and the introduction of Russian into their schools. Now they faced the same problem in the Canadian environment in spite of the guarantees they had received.

In 1880 Elder Johann Wiebe through a brotherhood meeting reorganized the Reinland Mennonite Church of the West Reserve, making adherence to the old principles and practices a test of church membership. Many of the Old Colony Mennonites at this time joined the Bergthal group of the West Reserve, which had moved in from the East Reserve and had organized under the leadership of Elder Gerhard Wiebe of the East Reserve an independent church with Johann Funk as elder. However, Johann Funk was too progressive for some of the Bergthal Mennonites of the West Reserve. In 1890 most of the group rejected his leadership and organized what became known as the Sommerfeld Church, since its elder, Abraham Doerksen, lived in the village of Sommerfeld. Elder Johann Funk and his following continued under the name Bergthal Mennonite Church. In the East Reserve the Bergthal church became known as the Chortitz Mennonite Church, since its elder resided in the village of Chortitz. Thus by the turn of the century the descendants of the original Chortitza settlement in Russia had divided into the large Old Colony Mennonite Church of the West Reserve, with a less conservative Sommerfeld Church and a rather progressive Bergthal Mennonite Church near by, and a Chortitz Mennonite Church of the East Reserve which was spiritually and culturally most closely related to the Sommerfeld group. In addition to this there was the Kleine Gemeinde of Molotschna background represented in both East and West Reserve as a minority group. Although conservative in comparison to the Molotschna Mennonites in their attitude toward education and other questions which confronted the Manitoba Mennonites, they could be compared with the progressive Bergthal group led by Johann Funk.

In addition to the divisions caused by internal differences, new divisions occurred also because of the infiltration of new religious ideas and practices brought in from the outside. In 1882 representatives of the Church of God in Christ, Mennonite (Holdeman group), from Kansas to Ohio caused a break among the Kleine Gemeinde of the East Reserve which led to the organization of a Holdeman Church in the East Reserve which was joined by the Kleine Gemeinde elder and nearly half of the total group. By 1890 the Mennonite Brethren, who originated in Russia in 1860, had started a fellowship in the West Reserve at Winkler which became the nucleus of the various Mennonite Brethren congregations in Manitoba. The Evangelical Mennonite Brethren, originating at Henderson, Nebraska, and Mountain Lake, Minnesota, won followers at Steinbach among the Kleine Gemeinde and others, which led to the organization of a congregation of the group there at the turn of the century. In 1937 the Rudnerweide Mennonite Church was organized by Wilhelm H. Falk through the separation of a group from the Sommerfeld Mennonite Church, which was more evangelistic and more progressive. The migration of the most conservative element from Manitoba to Mexico and Paraguay, after World War I, and the coming of Mennonite immigrants from Russia after World Wars I and II, greatly affected and changed the spiritual and cultural life of the Mennonites in Manitoba.

The Bergthal Mennonite Church, which originated under the leadership of Johann Funk in 1890, spearheaded educational progress and helped H. H. Ewert in the establishment of the Mennonite Collegiate Institute at Gretna and the organization of the Canadian Mennonite Conference in 1902, which most of the non-Mennonite Brethren immigrants coming to Canada after World War I and World War II joined. Most of the congregations of this conference were members of the General Conference Mennonite Church, but the large Bergthal Church with almost 4,000 baptized members, remained outside the General Conference in the 1950s.

The following were the elders of the various groups. After the turn of the century Johann Wiebe, the leader of the Old Colony Mennonite Church, who was assisted by 12 ministers, was succeeded by Elder Johann Friesen, later in Mexico by Isaac M. Dyck. Jacob Froese became elder of the Old Colony Mennonites remaining in Manitoba. Elder Abraham Dorksen of the Sommerfeld Mennonite Church was assisted by 11 ministers. Elder David Stoesz of the Chortitz Mennonite Church of the East Reserve, who had succeeded Elder Gerhard Wiebe, was assisted by seven ministers. The Kleine Gemeinde had Abraham Dyck on the East Reserve and Jakob Kroeker of Rosenort as elders, each assisted by five ministers. Peter Toews, a former elder of the Kleine Gemeinde, was elder of the Church of God in Christ, Mennonite. David Dyck was elder of the Mennonite Brethren group at Winkler. Johann Funk, elder of the Bergthal Mennonite Church, was succeeded by Jacob Hoeppner in 1903. He was succeeded by David Schulz in 1926, who after 1953 had had a co-elder in Jacob M. Pauls.

Migration and Population Shifts

During World War I the school question and the resistance of the Old Colony Mennonites and other conservative groups of Manitoba to adjustment to the Canadian environment came to a showdown. The School Attendance Act passed in 1916 did not prohibit the attending of private schools, provided they conformed with the standard set up by the school administration, but once a private school was condemned, a public school was established with compulsory attendance. C. B. Sissons summarized the situation as follows: "When the war spirit got hold of the West, and to poor equipment were added the dual sins of pacifism and German speech, . . . recourse was had to compulsion." It was at this time of "persecution" that the thought of a migration into another country was born. Repeated delegations sent to the provincial and dominion Canadian governments were without success. The government was determined to break the resistance of the conservative Mennonites. Public schools were established in all Old Colony districts, and teachers were hired to hoist the flag each morning and lower it again each evening, but not a single child attended the schools. Thereupon attendance at public schools was made compulsory and punishment was administered when children did not attend the school. When repeated petitions to give the Mennonites the right to conduct their own schools were of no avail, a decision was reached to look for another country.

In 1919 two delegations went to South America, visiting Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay. Even Alabama and Mississippi were considered as places to settle. In 1920 the Old Colony Mennonites sent a delegation to Mexico. A second one followed in January 1921. They obtained a "Privilegium" very similar to that which they had once received from the Canadian government, which they presented to their constituency in Canada. On 1 March 1922 the first train left Plum Coulee, Manitoba, followed by three from Haskett, Manitoba on 2-11 March. Two more trains left Swift Current. All of these settled near Cuauhtemoc, Chihuahua, Mexico. The Old Colony Mennonites from Hague, Saskatchewan, settled in Durango, Mexico. By 1926, of the 4,926 Old Colony Mennonites of Manitoba 3,340 had moved to Cuauhtemoc. Only a few more than 1,000 of the approximately 3,250 Old Colony Mennonites of Swift Current, SK., and only 946 of the 3,932 of the Hague, SK, Old Colony Mennonites moved to Mexico. This indicated the willingness to migrate to Mexico was much weaker among the Old Colony Mennonites of Saskatchewan than in Manitoba where about three fourths of them participated in the migration. A smaller group of the Sommerfeld Mennonites of the West Reserve under the leadership of Abraham. Doerksen settled in Mexico in 1922 at Santa Clara, not far from the Old Colony Mennonites. During 1926-1927, 1,744 Sommerfeld and Chortitz Mennonites from Manitoba went to the Chaco, Paraguay, where they established the Menno settlement, the first one of a number of settlements established by Mennonites in that country, the later settlements being made by Mennonites from Russia. After World War II Chortitz and Sommerfeld Mennonites from Manitoba also went to Paraguay, establishing a settlement near Villarrica in the eastern part of the country. Of the 1,650 persons who first settled there about one third returned to Manitoba. After World War II, Old Colony Mennonites from Manitoba, Mexico, and Saskatchewan also established a settlement in the Peace River Valley of Alberta, near Fort Vermilion. Kleine Gemeinde Mennonites from Manitoba established a settlement near the Old Colony settlement at Cuauhtemoc in 1948, called Quellenkolonie.

Thus the most conservative element of the North American Mennonites located in Manitoba and Saskatchewan became trail blazers of Mennonite settlement in a wholly new cultural environment. They sought out an environment to which it would be least tempting to adjust themselves. This was Latin America. Probably 5,000 to 6,000 Mennonites left Manitoba after World Wars I and II for the new settlements. In the case of the Old Colony Mennonites a minority was left in Manitoba without leadership. In the case of the Sommerfeld and Chortitz Mennonites the majority in Manitoba stayed, which is also the case with the Kleine Gemeinde. The most conservative element of Mennonites was thus removed from Manitoba. This in itself was significant for the later development of the Mennonites of that province. However, the most important fact was that an almost equal number of Mennonites from Russia settled in Manitoba after World Wars I and II. Thus far Mennonites of Manitoba had been rural; many believed that to give up rural life for city life would mean to give up the Mennonite faith. With the coming of the Mennonites from Russia after World War I and the depression this was completely altered. Of the 2,000 Mennonite families which came to Manitoba in 1922-1930 about four fifths settled on farms, some of which had been left behind by the conservative element moving to South America and Mexico, while about one fifth located in Winnipeg. After World War II about 3,000 Mennonites from Russia came to Manitoba, mainly to Winnipeg. In the city the Mennonites were employed as laborers and established businesses, factories, etc. A number of Mennonite schools and congregations were established in Winnipeg, and the mid-1950s Mennonite population in the city made it, next to Amsterdam, the largest Mennonite city population in the world.

The rural areas of Manitoba were significant for the spread of the cooperative movement. By 1946 the Federation of Southern Manitoba Co-operatives, with 26 affiliated organizations, covered territory with a total population of about 20,000, which was almost exclusively Mennonite. The cooperative tended to replace the old institution of mutual aid which had served the Mennonites in decades past. Altona in the West Reserve became the center of numerous cooperative enterprises. In 1944 the Cooperative Vegetable Oils Limited was organized by some 800 farmers and businessmen in the Altona area. Less successful were the cooperatives on the East Reserve, where private enterprise prevailed.

Canadian Mennonite Conference Churches in Manitoba, 1954-1955

| Churches | Members | Total Population | Families | Ministers | Elders | Places of Worship |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arnaud | 124 | 244 | 45 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Bergthal | 2,089 | 3,390 | 944 | 24 | 2 | 20 |

| Bethel | 269 | 384 | 120 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Blumenort | 368 | 684 | 146 | 9 | 2 | 5 |

| Elim | 250 | 472 | 111 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Glenlea | 55 | 87 | 19 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Lichtenau | 132 | 201 | 55 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Niverville | 139 | 366 | 62 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Nordheim | 117 | 195 | 41 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Schonfeld | 154 | 253 | 61 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Schönweise (Winnipeg) | 1,477 | 2,249 | 478 | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| Springstein | 194 | 354 | 83 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Steinbach | 208 | 354 | 86 | 5 | 0 | 1 |

| Whitewater | 568 | 1,103 | 230 | 12 | 1 | 6 |

| Winnipeg | 224 | 325 | 80 | 6 | 1 | 0 |

| St. Vital | 59 | 100 | 21 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Scattered | 30 | 50 | 15 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 6,457 | 10,811 | 2,597 | 86 | 13 | 51 |

All except Bergthal were members of the General Conference Mennonite Church in 1955 . The Bergthal Mennonite Church worshipped at the following places: Morden, Winkler, Plum Coulee, Rosenfeld, Altona, Gretna, Halbstadt, Morris, Lowe Farm, Kane, Homewood, Carman, Graysville, St. Vital, MacGregor, Gladstone, Arden, Neu Bergthal, Steinbach, and Spencer.

(Statistics are based on reports by B. Ewert, "The Mennoniten in Manitoba." Mennonitisches Jahrbuch (1951); reports of 1955; Jahrbuch der Konferenz, der Mennoniten in Canada 1955; and other records.)

Manitoba Mennonite Conferences and Churches, 1955

| Church | Year Founded | Location |

| Chortitzer Mennonite Church | 1874 | East Reserve |

| Kleine Gemeinde Mennonite Church | 1874 | East & West Reserve |

| Old Colony Mennonite Church (Manitoba) | 1875 | West Reserve |

| Bergthal Mennonite Church | 1880 | West Reserve |

| Church of God in Christ, Mennonite | 1882 | East & West Reserve |

| Sommerfeld Mennonite Church | 1890 | West Reserve |

| Manitoba Conference of Mennonite Brethren Churches | 1890 | East & West Reserve |

| Evangelical Mennonite Brethren | 1894 | East Reserve |

| Canadian Mennonite Conference | 1902 | East & West Reserve |

| Rudnerweide Mennonite Church | 1937 | West Reserve |

| Hutterian Brethren | 1918 | West of Winnipeg |

Statistics of Manitoba Mennonite Churches, 1950

| Name | Location | Baptized Members | Total Population | Families | Ministers | Congregations |

| Chortitzer Mennonite Church | East Reserve | 1,684 | 3,516 | 800 | 12 | 6 |

| Kleine Gemeinde Mennonite Church | Steinbach & Morris | 1,920 | 3,800 | 1,000 | 20 | 6 |

| Old Colony Mennonite Church (Manitoba) | West Reserve | 638 | 1,465 | 360 | 5 | 4 |

| Bergthal Mennonite Church | West & East Reserves | 2,089 | 3,390 | 944 | 24 | 20 |

| Church of God in Christ, Mennonite | East Reserve & Morris | 773 | 1,500 | 350 | 12 | 4 |

| Sommerfeld Mennonite Church | Manitoba | 4,120 | 7,944 | 1,900 | 16 | 10 |

| Manitoba Conference of Mennonite Brethren Churches | East & West Reserve | 3,512 | 7,100 | 1,750 | 80 | 30 |

| Evangelical Mennonite Brethren | Steinbach, Stuartburn, Winnipeg | 400 | 800 | 200 | 3 | 2 |

| Canadian Mennonite Conference (including Bergthal) | East & West Reserve | 6,457 | 10,811 | 2,597 | 98 | 43 |

| Rudnerweide Mennonite Church | Rudnerweide | 1,716 | 3,400 | 853 | 24 | 20 |

| Emanuel Mission | Steinbach | 300 | 600 | 590 | ||

| Hutterian Brethren | West of Winnipeg | 1,900 | 18 |

The flow of Mennonites from the country to the city increased rapidly with the coming of the Mennonites from Russia after World War I, During the days of depression many of the daughters went to the city to do housework. They had to make a living and to pay off debts for their transportation from Russia to Canada. One of the settlements of Mennonites, North Kildonan on the outskirts of Winnipeg, grew to a modern suburb with numerous enterprises as well as two Mennonite churches. Winnipeg had a factory established by J. Klassen, the C. A. DeFehr and Sons' Importing and Sales Company, and numerous other enterprises. There was also the Concordia 50-bed hospital, and the Bethania Old People's Home on the bank of the Red River operated by the Mennonite Benevolent Society. Winnipeg was also the home of the Mennonite Brethren Bible College, and the Canadian Mennonite Bible College, established in 1947 and 1948 respectively. The Old Colony Mennonites were not permitted to go to Winnipeg, and if they did they were considered to have left the fold. In the 1950s Winnipeg with its 7,000 Mennonites had a larger Mennonite population than any other North American city. According to the census of Canada the Mennonite population of Winnipeg was 114 in 1921, 909 in 1931, 1,285 in 1941, and 5,751 in 1951. Other towns with a predominant Mennonite population in the East Reserve were Steinbach, Niverville, Grünthal; and in the West Reserve Winkler, Altona, Gretna, Plum Coulee, Rosenfeld, Lowe Farm.

During World War II approximately 2,453 Manitoba Mennonites served their country in Alternative Service as conscientious objectors. Almost an equal number served in the regular army. In addition to this a great number of men were exempted from service because they were farmers or teachers. During this time all the Mennonite congregations in Manitoba organized the Mennonite Peace Committee. The elders of the Sommerfeld, Chortitz, Bergthal, Rudnerweide, Kleine Gemeinde, Church of God in Chirist Mennonite, Evangelical Mennonite Brethren, and Old Colony Mennonites organized a Council. The executive committee of this Council had authority to negotiate with the government pertaining to all CO matters.

During World War I the Hutterites in the United States living on Bruderhofs underwent some hardships which led to their migration to Canada. Of the 17 Bruderhofs of South Dakota, 15 went to Canada in 1918-1925. In 1955 there were 23 Bruderhofs in Manitoba located west of Winnipeg, named as follows: Blumengart, Sturgeon Creek, Barrickman, Maxwell, Iberville, Rosedale, James Valley, Riverdale, Waldheim, Bon Homme, Milltown, Huron, Poplar Point, Elm River, Sunnyside, New Rosedale, Lakeside, Riverside, Rock Lake, Springfield, Bloomfield, Crystal Spring, and Oak Bluff. The total population of these 23 Bruderhofs was 2,600 in 1955. -- Cornelius Krahn

1990 Update

Manitoba is a province in central Canada in which Mennonites have lived since 1874. The 1991 census reported 73,450 Mennonite and Brethren in Christ living in Manitoba, a 64 percent increase since 1951. Part of this increase is due to the immigration of German speaking Mennonites from Paraguay and Mexico, and from the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics via Germany.

Most of the increase has been in the major city of Winnipeg, which, with 21,900 Mennonites as of 1991, was the city with the largest Mennonite population in the world at that time. In 1990 the 43 congregations in the city included congregations made up primarily of ethnic Chinese and Vietnamese Christians.

Church Developments

In the Conference of Mennonites in Manitoba a transition took place from multicongregation churches under the leadership of an elder to more or less autonomous congregations, each under the leadership of its own pastor. The Bergthal Mennonites, the largest of the multicongregation churches, with 20 places of worship in 1955, completed its dissolution in 1972. The resulting congregational units for the most part remained in the Conference of Mennonites in Manitoba. Since 1968 many of them have also joined the General Conference Mennonite Church (GCM). Several rural congregations of the Manitoba Conference of Mennonite Brethren Churches have closed since the 1950s, while a number of new ones have been begun in urban centers.

The Kleine Gemeinde, Rudnerweider, and Chortitzer Churches developed conference structures, with the first-named body becoming the Evangelical Mennonite Church in 1952, then adopting the name Evangelical Mennonite Conference (EMC) in 1960. The Rudnerweider church became the Evangelical Mennonite Mission Conference (EMMC, 1959), and the Chortitzer church became the Chortitzer Mennonite Conference (1972). The latter, however, has retained the elder as central leader.

Both the Sommerfelder Mennonites and Old Colony Mennonites experienced further divisions in the difficult process of trying to adjust to modern society without compromising essential aspects of the faith. This resulted in the formation of the Reinländer Mennonite Church (1958) and Zion Mennonite Church (1980). The Reinländer group in turn experienced a division in 1986, giving rise to the Friedensfelder Church.

Mission outreach resulted in a number of Cree and Saulteaux congregations relating to the Conference of Mennonites in Canada (CMC).

Since its founding in 1963, the Mennonite Central Committee (Canada) office has been located in Winnipeg.

Education, Publication, and Broadcasting

The Mennonite conferences actively promote higher education. Concord College (formerly the Mennonite Brethren Bible College) and Canadian Mennonite Bible College, founded in Winnipeg in the 1940s, have established formal relations with the two provincial universities in the city. Discussions regarding a federation of CMBC, Concord College and Menno Simons College (formerly the Mennonite Studies Centre of the University of Winnipeg) to form a new Mennonite university are ongoing in 1998. Steinbach Bible Institute moved to college status in 1978, sponsored jointly by the EMC, EMMC, Chortitzer Mennonite Conference and two other congregations in Steinbach. Some of the other Mennonite groups, on the other hand, continue to have reservations about any formal education beyond the minimum required by law. The result, according to the 1981 census, was that 36 percent of Mennonites age 15 and older had less than a grade nine education, while 12 percent had at least some university studies.

Manitoba has also been an important Mennonite publishing center. The Mennonitische Rundschau, published in Winnipeg since 1923, was purchased by the Christian Press in 1945 and continues to serve German-speaking Mennonite Brethren. Its English companion, the Mennonite Observer, founded in 1955, became the Mennonite Brethren Herald in 1961. Der Bote moved its publishing site from Rosthern, Sask., to Winnipeg in 1977 and continues to serve the General Conference Mennonite Church. The official paper of the Evangelical Mennonite Mission Conference, Der Leitstern (founded 1944), became the The EMMC Recorder in 1967 and was being published in Winnipeg in 1998. The Messenger, published biweekly in Steinbach, has been the English language organ of the EMC since 1962. The Mennonite Mirror, published ten times a year in Winnipeg by the Mennonite Literary Society, began in 1970. Die Mennonitische Post, founded in 1977 by MCC Canada, is published biweekly in Steinbach and serves German-speaking Mennonites with Canadian connections in Mexico, Bolivia, Belize, and other countries.

Among Mennonite book publishers the most active have been Kindred Press (Mennonite Brethren), CMBC Publications (Conference of Mennonites in Canada), the Mennonite Literary Society, and Derksen Printers in Steinbach. Centennial celebrations beginning in 1974 gave rise to a large number of local histories of Mennonite communities.

Mennonite church-produced radio programs date back to 1947. The founding of Radio Southern Manitoba by a group of Mennonite businessmen in 1957 greatly stimulated this activity. It broadcasts from transmitters in Altona, Steinbach, and Boissevain. In 1987 the CMM had weekly broadcasts in English, German, and Low German. MB Communications in Winnipeg aired programs in German, Low German, and Russian, while other groups had one weekly program. Participation in television broadcasting was more occasional, with only the MB "Third Story" a regular program.

Cultural Activities and Political Involvement

The combined Oratorio choir of the two Mennonite colleges in Winnipeg has performed annually in the main concert hall of the city. The Winnipeg Mennonite Children's Choir has gained international recognition, as have several Mennonite soloists.

A Mennonite Theatre Society was started in 1972 and a Mennonite Orchestra in the 1940s. A few novelists, poets, artists, and filmmakers have received widespread recognition. The Mennonite Heritage Village in Steinbach has preserved artifacts of the pioneer years. The Mennonite Historical Society has promoted research, writing, publication, and the collection of archival material.

From an earlier stance of aloofness, Manitoba Mennonites have become increasingly active in political affairs. Between 1969 and 1977 there was a 70 percent increase in the number of Mennonites voting in elections. Mennonites have regularly been elected to the provincial legislature since 1959, representing four different political parties. They have often been represented in the provincial cabinet since 1966, some in senior portfolios. In the provincial riding (electoral district) of Rhineland virtually all candidates in Provincial elections since 1962 have been Mennonite. Several Manitoba Mennonites have been elected to the national Parliament and one has been appointed to a cabinet minister's position.

Urbanization and Demographic Trends

Only 22 percent of Manitoba Mennonites were part of the rural farm population in 1981. The shift to urban centers and to rural nonfarm occupations does not reflect a decrease in total acreage farmed by Mennonites, rather it is an indication of the rapid mechanization that has taken place in the agricultural sector. This mechanization released a large pool of workers, making possible a very significant growth in industry in such predominantly Mennonite towns as Winkler, Steinbach, and Altona. By 1981, about 53 percent of the province's Mennonites lived in "urban" centers (population over 1,000).

The 5,940 Hutterian Brethren in Manitoba in 1981, an almost three-fold increase since 1950, continued to be almost exclusively (98 percent) a rural farming people. The few in urban settings were all below age 35. Hutterites as a group were considerably younger than Mennonites according to the 1981 census. Over half (52 percent) of the Canadian Hutterite population was below the age of 20, compared to 37 percent for Mennonites. On the other hand, only about 13 percent of Hutterites were over 45 years compared to 27 percent among Mennonites. -- Adolf Ens

Statistics of Manitoba Mennonite Churches, 1985

| Name | Number of Congregations | Members 1985 | Members 1950 | % Increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chortitzer Mennonite Conference | 9 | 1,800 | 1,648 | 9 |

| Church of God in Christ Mennonite | 12 | 1,406 | 773 | 82 |

| Conference of Mennonites in Manitoba | 47 | 11,021 | 6,547 | 71 |

| Evangelical Mennonite Brethren | 11 | 810 | 400 | 103 |

| Evangelical Mennonite Conference | 30 | 4,445 | 1,920 | 132 |

| Evangelical Mennonite Mission Conference | 14 | 2,213 | 1,760 | 29 |

| Mennonite Brethren | 32 | 5,721 | 3,512 | 63 |

| Northwest Mennonite Conference | 1 | 15 | - | - |

| Old Colony Mennonite Church | 4 | 941 | 638 | 47 |

| Reinländer Mennonite Church | 6 | 683 | - | - |

| Sommerfelder Mennonite Church | 13 | 3,981 | 4,120 | -3* |

| Unaffiliated Mennonite | 5 | ? | - | - |

| Hutterian Brethren | 18 | 5,940** | 1,990** | 198 |

| * includes loss of Reinländer ** total population | ||||

Bibliography

Statistical data taken from the 1981 Decennial Census of Canada and from the annual yearbooks of the various Mennonite conferences.

Additional information is available in periodicals, especially the Canadian Mennonite, Mennonite Reporter, and Mennonite Mirror.

General Studies:

No comprehensive new study comparable to E. K. Francis, In Search of Utopia, (1955) has appeared.

Reimer, Margaret Loewen. One Quilt, Many Pieces. Waterloo: Mennonite Publishing Service, 1983 is a concise reference guide to Mennonite groups in Canada, including Manitoba.

Helpful studies of the former East Reserve area are:

Warkentin, Abe. Reflections on Our Heritage. Steinbach: Derksen Printers, 1971.

Loewen, Royden. Blumenort. Blumenort: Blumenort Mennonite Historical Society, 1982.

Penner, Lydia. Hanover: One Hundred Years. Steinbach: R. M. of Hanover, 1982.

For the former West Reserve area see:

Ens, Gerhard J. The Rural Municipality of Rhineland, 1884-1984. Altona: R. M. of Rhineland, 1984.

Gerbrandt, Henry J. Adventure in Faith. Altona: D. W. Friesen and Sons, 1970.

Zacharias, Peter D. Reinland: An Experience in Community. Reinland: Reinland Centennial Committee, 1976.

Bibliography for 1958 Article:

Correll, Ernst H. "Mennonite Immigration into Manitoba." Mennonite Quarterly Review 11 (July and October 1937).

Dawson, Carl. Group Settlement, Ethnic Communities in Western Canada. Toronto, 1936.

Epp, D. H. Die Chortitzer Mennoniten. Chortitz, Russia.

Erfahrungen der Mennoniten in Canada wahrend des zwieiten Weltkrieges 1939-1945.

Ewert, Benjamin. "Die Mennoniten in Manitoba." Mennonitisches Jahrbuch (1951).

Ewert, H. H. "Die Mennoniten in Manitoba." Bundesbote Kalender (1903): 31-35.

Francis, E. K. In Search of Utopia. The Mennonites in Manitoba. Altona, MB: D.W. Friesen, 1955.

Francis, E. K. "Mennonite Contributions to Canada's Middle West." Mennonite Life 4 (April 1949).

Fretz, J. W. "The Renaissance of a Rural Community." Mennonite Life 1 (January 1946): 14.

Galbraith, J. F. The Mennonites in Manitoba, 1875-1900. Manitoba, 1900.

Gott, Karl. "Bei den russlanddeutschen Mennoniten in Manitoba, Kanada." Mitteilungen des Sippenverbandes der Danziger Mennoniten-Familien . . . 1939: 28-31.

Harder, David. "Von Kanada nach Mexiko." Unpublished manuscript, Mennonite Library and Archives, Bethel College (North Newton, Kansas, USA)

Hedges, J. B. Building the Canadian West: The Land Colonization Policies of the Canadian Pacific Railway. New York, 1939.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe; Schneider, 1913-1967: III, 14-16.

Hoeppner, J. N. "Early Days in Manitoba." Mennonite Life 6 (April 1951): 11.

Jahrbuch der Konferenz der Mennoniten in Canada 1955.

Janzen, David. "A Sociological Study of the Mennonites of Winnipeg." Unpublished manuscript.

Journals of the House of Commons of the Dominion of Canada . , . Session 1886, printed by order of the House of Commons.

Krahn, Cornelius. "Adventure in Conviction. Russia, Canada, Mexico." Unpublished manuscript.

Krahn, Cornelius, ed. From the Steppes to the Prairies. Newton, KS, 1949.

Lehmann, Heinz. Das Deutschtum in Westkanada. Berlin, 1939.

Leibbrandt, George. "Emigration of the German Mennonites from Russia to the United States and Canada in 1873-1888." Mennonite Quarterly Review 6-7 (October 1932 & January 1933).

"Old Colony Mennonites and Hutterites." Record Groups No. 85. Microfilm, Mennonite Library and Archives, Bethel College (North Newton, Kansas, USA)

Peters, Klaas. Die Bergthaler Mennoniten & deren Auswanderung aus Ruszland & Einwanderung in Manitoba. Hillsboro, KS.

Peters, Victor. "Manitoba Roundabout, a Pictorial Survey." Mennonite Life 11 (July 1956): 104-109.

Quiring, Walter. Russlanddeutsche suchen eine Heimat. Stuttgart, 1938.

Records of the Bureau of Immigration . . . , Files 54623/130 and 54623/130H, April 21, 1919-Nov. 10, 1931, The National Archives of the U.S., 1934. Microfilm, Mennonite Library and Archives, Bethel College (North Newton, Kansas, USA)

Rempel, J. G. Funfzig Jahre Konferenzbestrebungen 1902-1952. Steinbach, MB, 2 vols.

Rempel, W. "Die Mennoniten in Süd-Manitoba." Bundesbote Kalender (1898): 36.

Schäfer, Paul J. Die Mennoniten in Canada. Altona, MB, 1947.

Schaefer, P. J. "Heinrich H. Ewert—Educator of Kansas and Manitoba." Mennonite Life 3 (October 1948): 18.

Schaefer, Paul J. Heinrich H. Ewert. Lehrer, Erzieher und Prediger der Mennoniten. Gretna, MB, 1945.

Schmiedehaus, Walter. Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott. Cuauhtemoc, Mexico, 1948.

Shantz, Jacob Y. Narrative of a Journey to Manitoba, Together with an Abstract of the Dominion Lands Act and an Extract from the Government Pamphlet on Manitoba. Ottawa, 1873.

Siemens, J. J. "Sunflower Rebuilds Community." Mennonite Life 4 (July 1949): 28.

Sissons, C. B. Bilingual Schools in Canada. London, 1917.

Sixty Years of Progress. Diamond Jubilee, 1884-1944. Altona, MB, 1944.

Smith, C. Henry. The Coming of the Russian Mennonites. Berne, IN, 1927.

Thiessen, J. J. "Present Mennonite Immigration to Canada." Mennonite Life 4 (July 1949).

Totten, Don E. "Agriculture of Manitoba Mennonites." Mennonite Life 4 (July 1949): 24.

Waisenverordnung der Reinlander Mennoniten Gemeinden . . .

Wall, Johann P. "Diary, 1919." Microfilm, Mennonite Library and Archives, Bethel College (North Newton, Kansas, USA)

Wall, Johann P. "Statistics of the Old Colony Mennonites from 1910 ff." Microfilm,Mennonite Library and Archives.

Wiebe, Gerhard. Ursachen und Geschichte der Auswanderung der Mennoniten aus Russland nach Amerika. Winnipeg, MB.

Yoder, S. C. For Conscience Sake. Goshen, IN: Mennonite Historical Society, 1940.

Various yearbooks and conference reports.

| Author(s) | Cornelius Krahn |

|---|---|

| Adolf Ens | |

| Date Published | 1989 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Krahn, Cornelius and Adolf Ens. "Manitoba (Canada)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1989. Web. 22 Apr 2025. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Manitoba_(Canada)&oldid=142796.

APA style

Krahn, Cornelius and Adolf Ens. (1989). Manitoba (Canada). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 22 April 2025, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Manitoba_(Canada)&oldid=142796.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 3, pp. 457-466; vol. 5, pp. 533-536. All rights reserved.

©1996-2025 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.