Church of God in Christ, Mennonite (CGC)

1953 Article

The Church of God in Christ, Mennonite, is the result of a spiritual awakening through the instrumentality of John Holdeman in 1859. John Holdeman was born 31 January 1832 near New Pittsburg, Wayne County, Ohio. His parents, Amos and Nancy (Yoder) Holdeman, were members of the Mennonite Church (MC), in which faith John Holdeman was brought up. He was a thoughtful and impressionable youth, and at the age of 12 years he had a definite religious experience of the new birth and forgiveness of sins. He reconsecrated his life at the age of 21 and was at that time baptized and received into the Mennonite Church (MC) by Bishop Abraham Rohrer in October 1853. For several years he was connected with the above-named church and in consequence of being a member of this church, he was brought to perceive more fully and clearly the decay and the errors into which he believed the church had drifted, which wrought within him much prayerful concern and travail of soul. His understanding of the condition of the church was, he believed, revealed to him by the Lord. He stressed the absolute necessity of the new birth and being baptized with the Holy Ghost, as well as a return to the faith of the fathers in practicing a more spiritual child training, disciplining unfaithful members, Scriptural avoidance of apostates, avoiding of worldly minded churches, associations, etc.

Being of a zealous mind and of energetic convictions, though endeavoring to follow peace with all men, he nevertheless, as he says, soon discovered opposition on the part of those who were not willing to yield to his pleas for a return to the primitive Gospel way of life and doctrine. This was the primary and fundamental cause of the cleavage which, six years after his admission into the Mennonite Church, resulted in his separation from that brotherhood, after all efforts to work in fellowship on the old ground and foundation failed, which he had sought with much concern, prayer, supplication, and pleadings with the elders of the church.

In 1859 John Holdeman with a number of others began to hold separate meetings. Not long after, others joined with John Holdeman laboring and preaching as they believed in the old-time Gospel. He soon established a separate organization which was named "The Church of God in Christ, Mennonite." The newly organized church struggled with and weathered many difficult trials, and for a time progressed slowly until other brethren united in the labors with him so that the faith was carried to different states and Canada, where congregations were formed. The first brethren to be ordained into the ministry were Frank Seidner and Mark Seiler, both of Ohio, men of spiritual gifts and power. Soon others followed, including Peter Toews and Wilhelm Giesbrecht of Manitoba, Tobias A. Unruh of Kansas, F. C. Fricke of Michigan, and H. J. Mininger of Pennsylvania.

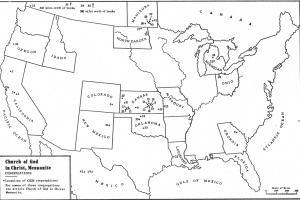

When the immigration of Mennonites from Russia took place in 1874 and later, quite a few of their number joined the Church of God in Christ, Mennonite, both in Kansas and in Canada. Many of the Mennonites of the Kleine Gemeinde, under the leadership of Elder Peter Toews and Wilhelm Giesbrecht, were united to the faith. And in Kansas, Tobias A. Unruh (a former minister from the General Conference Church) and Benjamin Schmidt were active in bringing many into the church; also David Holdeman of Hesston, Kansas, formerly of Indiana, did much in promoting the new congregations. The church began to increase and to spread to different states in the United States and to different provinces in Canada, until in 1949 there were 41 congregations in the United States and Canada, with a baptized membership of about 4,500, including 88 ministers and 62 deacons. The church had mission stations in Mexico and New Mexico with three ordained Spanish ministers, and an Indian mission station in Canada.

Elder John Holdeman believed in a true lineage of the church of God, and stressed that to claim this lineage the church must believe and practice the same confession of faith through the centuries from the time of the apostles to the end of the world. He taught that the church was established on the day of Pentecost and continued through the centuries until this present time, having like faith and practice, emphasizing that "... upon this rock [Christ] I will build my church; and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it" (Matthew 16:18). John Holdeman believed and taught and the church believes and teaches likewise that the Holy Scripture is the inspired Word of God and the infallible guide whereby all doctrine and teaching must be governed. It accepts the Eighteen Articles of Faith (Dordrecht Confession) as drawn up at a peace convention at Dordrecht, Holland, 21 April 1632, as a true evangelical confession. These articles are taught and practiced throughout all the churches. This denomination also accepts doctrines not so clearly set forth in the Eighteen Articles, such as nonconformity to the world in dress, bodily adornment, worldly sports and amusements.

The church holds to a twofold ministry, viz., elders or bishops (ministers), and deacons. While elders may differ in gifts and hence in responsibility, officially they are all equal. Baptism is administered by pouring to those that have been born again, having received remission of sins through the atoning blood of Christ, and are willing to conform their life to the faith and practice of the church. The church accepts as obligatory the great commission, "Go ye therefore, and teach all nations " in obedience to our Lord and Master as well as the constraint of the love of Christ and the responsibility toward our fellow men. It believes that the letter and the spirit of the Gospel are emphatically against strife, contention, and carnal warfare and that, therefore, no believer should have any part in carnal strife, whether between individuals, in lawsuits, or in conflicts between nations; that church and state, although both ordained of God, are separate institutions and serve different purposes; that believers should have no part in oath-bound secret organizations and that membership in such disqualifies them for church membership; and that Christian people should be temperate in all things lawful and abstain from the use of intoxicants, tobacco, and kindred carnal habits.

The nonmillennial or amillennial view of Christ's reign and kingdom on earth is accepted as Scriptural. The church teaches that the present dispensation is the last and only time in which salvation is offered, and that at the second advent Christ will receive the redeemed and judge the world in righteousness; and that Christians should "follow peace with all men, and holiness, without which no man shall see the Lord" (Hebrews 12:14). The governing body of the church is the General Conference, whose decisions are binding upon all members of the church, and which convenes on the decision of a two-thirds affirmative vote of all ministers, deacons, and delegates.

The church has an active mission board, a publication board, and other committees deemed appropriate to the furtherance of its activities. In 1953 it operated Mercy Hospital at Moundridge, Kansas.; two homes for the aged, Bethel Home at Montezuma, Kansas, and Linden Home at Linden, Alberta; and the Bethel Hospital at Cuauhtemoc, Chih., Campo 45, Mexico. Its periodicals were Messenger of Truth, Goltry, Oklahoma, and Botschafter der Wahrheit, Steinbach, Manitoba.

In 1953 the church had the following number of congregations: California, 3; Colorado, 1; Florida, 1; Idaho, 1; Kansas, 14; Louisiana, 1; Michigan, 2; Missouri, 1; North Dakota, 2; Ohio, 1; Oklahoma, 3; Oregon, 1; British Columbia, 1; Alberta, 3; Manitoba, 5; Georgia, 1; and Mexico, 2. One mission station in New Mexico and one in Alberta had a membership of 20. The total membership was 5,308, of whom 1,334 were in Canada. -- PGH

1989 Article

The Church of God in Christ, Mennonite (CGC), often referred to as the "Holdeman Mennonites," was one of several 19th-century offshoot movements from (Old) Mennonite (MC) and Amish churches. At that time, Americanizing influences (acculturation) and internal adjustments and shifts overwhelmed a number of traditionalist, isolation-prone Mennonites, resulting in many frustrated members (see John F. Funk, The Mennonite Church and Her Accusers, 1878). True to their Anabaptist moorings, they sought to be restitutionist (restorationist) and were therefore inclined toward secession.

John Holdeman, the energetic "prophet-founder" of this group, was born on the newly settled frontier of Wayne County, Ohio, to (Old) Mennonite parents. His father, Amos, was interested in "true lineage" aspects of church history and the revival movements of his day—particularly the Methodist-influenced Church of God (Winebrennarians). At midcentury Winebrennarians were strong in some areas where Mennonites resided, but the revivalism associated with the Winebrennarians was largely rejected by North American Mennonites until the turn of the century. Amos Holdeman's interest in this probably stimulated the interest of his son John, who reported having a definite religious experience of new birth and forgiveness of sins at age 12. It is believed that this happened under the revivalistic preaching of Jacob Keller and Thomas Hickernell at a nearby Church of God. By the time he was 20, however, he reported that he had become "a wicked sinner." Following his marriage to Elisabeth Ritter on 18 November 1853, he went through "dark experiences" until 1854, when he finally experienced "release and received joyful light and quiet conscience" and was baptized (October). He reported having visions and dreams, a call to ministry, and "special power and love as never before." This moved him to study the Bible, writings of Menno Simons and Dirk Philips, and Martyrs' Mirror.

In the decade that followed, he was disturbed by the "decay" he observed in Mennonite churches and conferences that he visited or read about. His exhortations to other Mennonites went unheeded. He was not invited to speak or ever nominated for "the lot" as a candidate for the ministry. Meanwhile, he continued to experience visions and dreams about the nature of the "true church." Discouraged by the lack of response to suggested reforms, he finally called his own meeting in April 1859. This became the beginning of the Church of God in Christ, Mennonite -- for him a continuation of the "true lineage church" which he now considered the carrier of the "candle-stick."

He stressed the necessity of experiencing genuine rebirth before being baptized (by pouring). Many of his emphases were based on traditional Mennonite teachings -- more faithful and consistent church discipline and avoiding the excommunicated, the practice of nonresistance, etc. The 12 books and booklets he authored between 1862 and 1889 (eight in German, four in English) reflect this, as do many exhortations in periodical articles and private letters pertaining to lax practices and the "heresies" of his time. His major work, Spiegel der Wahrheit (612 pages), has been available and broadly used by his adherents in an English translation (Mirror of Truth) since 1956.

His hoped-for following among Mennonites and Amish was minimal. Only 150 joined over two decades (1860-1880). Some estimated that his movement, like most of the other 19th-century Mennonite spin-off groups, would soon have ceased to exist, had it not been for a major growth spurt after 1878, when some immigrant Mennonites from Prussia, coming from an ethnically different background, were attracted to him. These came largely from frustrated, landless "Polish Russians" from the Ostrog area, and from some spiritually troubled Kleine Gemeinde Mennonites, from South Russia's Molotschna area, who had experienced traumatic, internal divisions.

The Ostrogers were the progeny of the conservative Groningen Old Flemish from Holland. They were semiliterate, financially impoverished, and perceived by others as being "spiritually needy." At the time of their settlement in McPherson County, Kansas, in 1875 they were referred to as the "Destitute Poles." These 500 immigrants found it impossible to assimilate with the existing General Conference Mennonite Churches in Kansas which most other "Kirchliche" Mennonite immigrants joined. Differences in culture and lifestyle were too great. John Holdeman was attracted to these Ostrogers. And they seemed to be ripe both for what he had to say and the way he related to them, even though, by this time, most American Mennonites had rejected him. In 1878 be baptized 78 of them.

Three years later he baptized another 118 in Manitoba. These were Kleine Gemeinde Mennonites who had migrated to North America. About two-thirds of these had settled in Manitoba and the other third near Janzen, Nebr. Disagreements about leadership among themselves had developed in Russia, resulting in this decision to locate at a distance from each other. Those who came to Manitoba with their leading elder, Peter Toews, represented the more progressive of the Manitoba group. This was the portion that joined Holdeman's movement.

This 1878-1881 growth spurt more than tripled the number of Holdeman's followers by 1882. Membership in the CGC in the 1980s still reflects their progeny. About 45-50 percent come from the McPherson County group with names like Koehn, Schmidt, Unruh, Jantz, Becker, Nightengale, Wedel, Ratzlaff, Jantzen/Johnson. About 25-30 percent have a Manitoba background with names like Toews, Penner, Friesen, Giesbrecht, Loewen, Isaac, Wiebe, Reimer. About 10-15 percent are from Holdeman's own Swiss-South German background with names like Holdeman, Leatherman, Litwiller, Yost. Among the remaining 10-15 percent a few names like Fricke and Mastre stand out.

During his lifetime, Holdeman moderated the first seven conferences held by the group. These dealt largely with the shaping of doctrinal emphases and resolving some ongoing internal tensions, as well as conflicts with some people outside the CGC. The minutes of the seventh conference (1896), together with minutes from 20 subsequent conferences, continue to be used as the binding directives that guide CGC members.

In the last two decades of his life, Holdeman was plagued by increasing financial indebtedness incurred from his poor farm management and overinvestment in publishing his own writings; a rejection of his movement by his own mother and two of his three living children; and his father's ill health and addiction to tobacco. Leaders who left the group openly contested the validity of Holdeman's ordination, which he claimed needed no human "laying on of hands" since be had already been "ordained by God." A successful lawsuit of $2,000 was won against him and three of his colleagues for their role in encouraging a CGC member in practicing marital avoidance of her excommunicated CGC husband.

A little more than two years before his death he began to edit and publish the first conference periodical, Botschafter der Wahrheit. Holdeman resided in Wayne County, Ohio, from 1832 to 1883; Jasper County, Missouri, USA). (1883-97); and McPherson County, Kansas. (1897-1900). It is estimated that he spent the equivalent of 13 years traveling and preaching in 17 states of the United States and two provinces of Canada, visiting at least 112 locations. When he died in 1900 the CGC membership numbered approximately 750.

The decade after Holdeman's death was difficult for the group. No strong leadership emerged until an earlier convert to the CGC from Lutheran parentage, Fredrick C. Fricke (1867-1947), took leadership in 1909.

During the first half of the 20th century the CGC faced a number of demanding changes: going through the transition from German to English; facing the compulsory draft and maintaining a strict conscientious objector stance through the two World Wars; adapting to some Americanization; finding new ways to deal with the emergence of technology (farm machinery, radios, television, etc.); standardizing the yearly revival meeting method as the major church disciplining process; establishing conference channels for emerging mission and evangelistic thrusts and publications; and moving away from leadership by elders.

The Church of God in Christ, Mennonite grew from 5,000 to 8,500 members between 1950 and 1970. During these two decades missionary efforts intensified domestically and abroad (Mexico, Nigeria, Haiti, India, Brazil). Service and ministry involvements also developed, including extensive tract dissemination, relief efforts, and disaster assistance, leading to the development of the Christian Disaster Relief Board. They developed health care institutions (Grace Nursing Home, Livingston, California; Bethel Home, Montezuma, Kansas; Greenland Home, Ste. Anne, Manitoba; Linden Nursing Home, Linden, Alberta; and Valhaven Home, Mt. Lehman, British Columbia, among others) and moved toward more centralization by erecting a building for conference functions, including offices for Gospel Publishers, at Moundridge, Kansas, and Ste. Anne, Manitoba. Two mutual aid organizations, Mennonite Union Aid and Brotherhood Auto Aid, serve the church. Some felt there was serious spiritual "decay." A few groups defected from the CGC seeking a restoration of John Holdeman's emphases. None of these were large movements, nor did lasting offshoots materialize.

Since 1970 other issues have surfaced. One of the most frequently addressed and demanding was the growing affluence within the membership (a few members had become millionaires). Because of higher land costs and a growing membership more were forced to find occupations outside agriculture, which increased relationships with people outside the CGC. Many traveled widely and experienced a broadened understanding of the world. The defection level increased with more members and more questioning the central doctrinal emphasis of being "the true church."

By the mid-1970s, frustration about the common church disciplining process of yearly revival meetings triggered a "new way" of dealing with deviants. An intensive, highly personal, probing method usually referred to as "paneling" was introduced. Those who observed the often-traumatic effects of life-probing thoughts and the sought-after behavior correctives referred to the method as "purging" or even "witch-hunting." An exceptionally large number were "disciplined" and many were excommunicated. The level of bitterness felt by those who had been disciplined, as well as a general emotional depression, was noted by those who lived close to CGC congregations. The steady growth in membership of the CGC declined between 1976 and 1979. The largest drop was experienced in Manitoba, where the "paneling" was most severe. Since then the yearly revival meeting pattern of church discipline has returned.

Another threat felt for many years resulted in the establishment of 87 private elementary schools by 1987 in response to a formal decision reached at the 1974 conference. The encroaching worldliness of the peer pressures in the public schools, along with curriculum developments, use of television, and the physical education requirements, triggered this. Virtually the entire North American membership of 12,694 in 111 congregations in 1990 had access to private schooling taught largely by those who had themselves completed the eighth grade.

Church of God in Christ involvement in missionary endeavors by 1987 was evidenced by the fact that more than 150 members were involved in overseas assignments. These assignments took place in the following countries (membership in parentheses): Belize (24), Brazil (208), Dominican Republic (20); Guatemala (21), Haiti (318), India (27), Mexico (375), Nigeria (203), and the Philippines (183). Additional relief work, tract distribution, and evangelism has taken place in several other countries. Non-North American membership of 1,801 in 1996 was about 10 percent of the total worldwide membership of 16,606. Of the 14,805 members in North America, 3,768 were found in Canada (eight provinces) and 11,037 in the United States (31 states). Approximately one-third of the United States membership resided in Kansas, and more than 40 percent of the Canadian membership lived in Manitoba. The church's periodical is Messenger of Truth.

Church of God in Christ beliefs continue to reflect conservative strains of the Anabaptist and Mennonite traditions. They regard six confessions of faith important, beginning with the "[33 articles" found in Martyrs' Mirror. The most recent confession was accepted in 1959. Holdeman beliefs pertaining to the supernatural, the Bible, salvation, and eternal destiny are similar to those of evangelical Protestants. Their distinctions are largely those seen among conservative Mennonites of the past four centuries. Beliefs unique to them are the authority they have tended to give to dreams, visions, and revelations and their adherence to the docetic "celestial flesh" Christology of Menno Simons (and Melchior Hoffman). Their most often noted doctrinal emphasis is their "true church" doctrine coupled with a carefully defined and monitored lifestyle faithful to their worldview.

Beliefs and accepted practices have been carefully defined with little room left for doubt as to what is "right" or "wrong." These begin with an emphasis on being redeemed from sinfulness, which results in an emulation of Christlikeness, focused both on attitudes and outward expressions in appearance, family and community relationships, vocation, and possessions. The decisions reached on these matters at conferences are binding. Unheeded infractions usually result in discipline, particularly during the yearly revival meetings. This has forced a fairly standard outward conformity: men wear relatively plain dress and beards; they avoid wearing ties. Women also dress simply and wear black head coverings (either a small cap or a kerchief tied under the chin. These symbols continue to serve as powerful reminders of religious obligations of being a faithful Holdeman Mennonite. Deviations in appearance signal tendencies toward defection and are dealt with by peer pressures of fellow church members, family, ministers, deacons, and the visiting ministers during their revival meetings. Observers have noted that they have managed to retain one of the most carefully disciplined groups in this respect in North America.

Typical of many evangelical and/or conservative Christians, CGC members normally gather Sunday mornings for Sunday school and worship and Sunday and Wednesday evenings for teaching, fellowship, and music-making. Ministers are chosen from their own ranks without formal training for pastoral ministry. Usually there are several in one congregation. They, together with ordained deacons, comprise the church staff, which takes major responsibility for local church matters. There is no regularly salaried minister. Most members and ministers have traditionally been farmers.

They worship in comfortable but relatively plain buildings which may include loudspeaker systems, air-conditioning, padded pews, and carpeted floors, but no musical instruments. They have no regular choirs but sing in four-part harmony, drawing on hymnody that makes heavy use of gospel songs. Ministers tend to preach topically rather than exegetically and seldom use prepared notes.

Erring members are warned. If this goes unheeded they are ultimately excommunicated and avoided (shunned) by fellow members. It is estimated that about 10-25 percent experience excommunication. The fact that about 75-80 percent "repent" and return and are re-accepted attests to the success of their socialization and the feared experience of avoidance. Most important decisions are made at the conclusion of yearly revival meetings after they have observed footwashing (symbolizing their revival meeting "cleansing"), communion, baptisms, re-acceptance of repentant excommunicants, and the calling and ordination of ministers and deacons as needed.

They have a tightly knit, closed system of church member control centered in their "true church" concept; an insistence on unity in doctrine and practice; unquestioned following of their ordained leaders; decision making relegated basically to the ordained men; and a rigid doctrine and practice of church discipline which is coupled with the threat of eternal penalty. Attendance at other churches and participation in intimate spiritual relationships with nonmembers are regarded as bordering on "spiritual adultery" or listening to "false prophets."

In communities where they reside they are generally respected, particularly for their care and concern, willingness to help, reliability in work, and ethical ways. They are regarded as a people who continue to take their Christian doctrines and responsibilities very seriously, seeking to deal with seductive, world-conforming agendas in every way.

See also Église de Dieu en Christ Mennonite, Haiti

Bibliography

Boynton, Linda Louise. The Plain People: An Ethnography of the Holdeman Mennonites. Salem, Wis.: Sheffield Publishing Company, 1986.

Church of God in Christ, Mennonite Yearbook (1996).

Conference Reports From 1896-1950, Church of God in Christ, Mennonite (Cumulative).

The Confession of Faith and Minister's Manual of the Church of God in Christ, Mennonite. 2nd ed. 1952?.

Hiebert, Clarence. The Holdeman People: The Church of God in Christ, Mennonite, 1859-1969. South Pasadena, Calif.: William Carey Library, 1973.

Histories of the Congregations of the Church of God in Christ, Mennonite. Moundridge, Kans.: Gospel Publishers, 1975.

Holdeman, John. A History of the Church of God. Lancaster, 1876.

Holdeman, John. The Old Ground and Foundation. Lancaster, 1863

Mennonite World Handbook (MWH), ed. Paul N. Kraybill. Lombard, Ill.: Mennonite World Conference [MWC], 1978: 324-27.

Mennonite World Handbook. Strasbourg, France, and Lombard, Ill.: MWC, 1984: 136.

Mennonite World Handbook, ed. Diether Götz Lichdi. Carol Stream, Ill.: MWC, 1990: 411

Penner, John. A Concise History of the Church of God. Hillsboro, KS, 1951?.

Year Book of the Church of God in Christ, Mennonite, 1944-

Additional Information

Website: Church of God in Christ, Mennonite

Articles of Confession (Church of God in Christ, Mennonite, 1896)

A Statement of the Christian Doctrines of the Church of God in Christ, Mennonite (1925)

| Author(s) | P. G., Clarence Hiebert Hiebert |

|---|---|

| Otis E. Hochstetler | |

| Date Published | 1989 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Hiebert, P. G., Clarence Hiebert and Otis E. Hochstetler. "Church of God in Christ, Mennonite (CGC)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1989. Web. 24 Nov 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Church_of_God_in_Christ,_Mennonite_(CGC)&oldid=100403.

APA style

Hiebert, P. G., Clarence Hiebert and Otis E. Hochstetler. (1989). Church of God in Christ, Mennonite (CGC). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 24 November 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Church_of_God_in_Christ,_Mennonite_(CGC)&oldid=100403.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, pp. 598-600; vol. 5, pp. 154-157. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.