Difference between revisions of "Palatinate (Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m (Text replace - "emigrated to" to "immigrated to") |

m (Text replace - "<em>Mennonite Quarterly Review</em>" to "''Mennonite Quarterly Review''") |

||

| Line 94: | Line 94: | ||

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. <em>Mennonitisches Lexikon</em>, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. II, 588-600 (Kurpfalz), 356-577 (Pfalz-Zweibrucken), 357-59 (Pfälzische Kirchenordnungen), 492-94 (Rheinland-Pfalz); v. III, 490 f. | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. <em>Mennonitisches Lexikon</em>, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. II, 588-600 (Kurpfalz), 356-577 (Pfalz-Zweibrucken), 357-59 (Pfälzische Kirchenordnungen), 492-94 (Rheinland-Pfalz); v. III, 490 f. | ||

| − | Hein, Gerhard. "The Development of the Mennonite Hof of the Seventeenth Century Palatinate into the Mennonite Churches of Pfalz Rheinland Today." | + | Hein, Gerhard. "The Development of the Mennonite Hof of the Seventeenth Century Palatinate into the Mennonite Churches of Pfalz Rheinland Today." ''Mennonite Quarterly Review'' (1955): 188-96. |

Hein, Gerhard. "Unsere Gemeinden in der Pfalz vor 200 Jahren und heute." <em>Der Mennonit</em> IX (1956): 138-40, 154 f., 170 f. | Hein, Gerhard. "Unsere Gemeinden in der Pfalz vor 200 Jahren und heute." <em>Der Mennonit</em> IX (1956): 138-40, 154 f., 170 f. | ||

Revision as of 23:08, 15 January 2017

Introduction

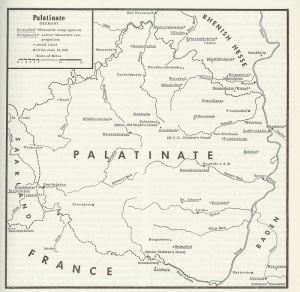

Palatinate is a region of the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate since 1945. From 1815 to 1918 it belonged to the kingdom of Bavaria, and still earlier (until 1801) known as the Kurpfalz or Pfalzgrafschaft bei Rhein, which extended across the Rhine and had (until 1720) Heidelberg as its capital and later (until 1778) Mannheim. Enclosed by the Palatinate were the bishoprics of Worms and Speyer. In the realm of the Kurpfalz lay the duchies (e.g., Pfalz-Zweibrücken), several principalities (e.g., Simmern, Veldenz, and Lautern) and graviates (e.g., Leiningen, Falkenstein, Wartenberg, and parts of Sponheim). For a long time the Upper Palatinate (since 1918 in Bavaria) was politically connected with the Palatinate on the Rhine.

Since early times the Palatinate has been splintered politically as well as religiously. In accord with the principle of cuius regio, eius religio, most of the population changed its faith five times in the 16th century. Catholic doctrine, supported by Elector Ludwig V (d. 1544), was followed by the Lutheran under Friedrich II (d. 1556) and Otto Heinrich (d. 1559), the Reformed under Friedrich III (d. 1576), again the Lutheran under Ludwig VI (d. 1583), and finally the Reformed under Johann Casimir (d. 1592). These ecclesiastical changes were one of the factors that made it possible for Anabaptism to enter the Palatinate early and to develop—in spite of much resistance—to considerable strength.

Deep inroads were made into the post-Reformation history of the Palatinate by the Thirty Years' War (1618-48) and the French Revolution (1789-1815). Accordingly the 400-year history of the Anabaptists-Mennonites falls into three clearly defined eras: (1) from the origin of Anabaptism ca. 1525 to its almost complete extinction in the Thirty Years' War (100 years); (2) from the immigration of Swiss Mennonites from the middle of the 17th century until the reorganization of the Palatinate c1800 (150 years); (3) from the beginning of the freedom of the 19th century to the present (150 years).

From the origin of Anabaptism ca. 1525 to the Thirty Years' War

The origin of Anabaptism in the Palatinate presumably precedes the formation of the first congregation in Switzerland. Johannes Risser, pastor of the Sembach congregation in 1832-68, says that "already by 1522, and especially after the Peasants' Wars (1525)" there were Anabaptists in the Palatinate, although he fails to give any proof for the 1522 date. In 1526 Jakob Kautz, a native of the Palatinate (Grossbackenheim) and a Lutheran preacher at Worms, became an Anabaptist. In 1527 Hans Denck and Ludwig Haetzer were living in Worms and here published their German translation of the Prophets, which soon went through thirteen editions. Worms was probably also the scene of the first adult baptisms. "People from the Palatinate who were rebaptized at Worms are persecuted, imprisoned, and the same is happening in other provinces" (Nikolaus Thomae, priest of Bergzabern).

The leading Protestant clergymen of the Palatinate were not completely unsympathetic with the early Anabaptists. When Hans Denck, for example, on his flight from Nürnberg, Augsburg, and Strasbourg came to the Palatinate in early 1527 he was kindly received and heard by Nikolaus Thomae in Bergzabern. He wrote, "In a fraternal manner Denk dealt with us." They parted as friends, although in many respects their ideas differed. "When I accompanied Denk he earnestly admonished me to live a blameless life in accord with the Gospel, for which I am very grateful to him." In a letter to K. Hubert, Bucer's famulus, dated 28 January 1529, he says of five Anabaptists who were employed in building the prince's castle in Bergzabern that he associated with them "on an entirely friendly basis," for they were "God-fearing and honest people."

Soon after this Hans Denck was in Landau where Johannes Bader was promoting the Reformation. Bader was just on the point of writing his Brüderliche Warnung, a polemic against the Anabaptists who had a considerable following around Landau even before Denck's appearance there. Nevertheless Bader held a debate with Denck on 20 January 1527, on the question of infant baptism. It is worth noting how far Bader, in spite of the sharpness of his opposition, agreed with Anabaptist views, granting, for instance, that the baptism of infants does them no good "unless the parents at the right and proper time remind them of the baptism they have received." Nevertheless Bader did not hesitate to call for their forcible suppression by the state. In early 1528 a mandate was issued in Landau forbidding Anabaptists to stay there or the inhabitants to give them lodging, both on penalty of corporal punishment. But the question of infant baptism occupied Bader to his old age, although he leaned toward Schwenckfeld rather than the Anabaptists in this matter.

Suddenly the sharpest persecution set in against the Anabaptists. On 5 March 1528, the unstable Elector Ludwig V, 1508-1544, upon the insistence of Emperor Charles V, issued a mandate against the Anabaptists referring to the imperial mandate of 4 January 1528, which demanded capital punishment for Anabaptists. Soon many of the prisons were full to overflowing. In Alzey many lay "in arrest," as the elector wrote in 1528, "for a long time." A letter written by J. Cochlaeus to Erasmus on 8 January 1528, contains the information that eighteen Anabaptists were imprisoned for a considerable time at Alzey and had been before the court several times. In Germany their number had reputedly risen to 18,000.

The Anabaptist trial at Alzey created wide excitement. There was general uncertainty concerning the correct judgment of the Anabaptists, from the elector, who sought the advice of jurists and theologians, to the local officials, who kept asking for instructions. The Palatine Chancellor Florenz von Venningen in 1527 wrote an extensive document that argued that since the prisoners had accepted rebaptism they were to be punished by death. The document was sent for consideration to the juristic faculties at Cologne, Mainz, Trier, Freiburg, Ingolstadt, Tübingen, Erfurt, Leipzig, Wittenberg, and Heidelberg. Erfurt and Wittenberg declined to take a position, but the others expressed their agreement.

The Anabaptist prisoners of Alzey were warmly defended by Johann Odenbach, the Protestant pastor of Obermoschel. His "Sendbrief und Ratschlag" to the judges tells them that they have treated many criminals better in prison than these poor people who have committed no crime but have merely in error had themselves baptized. "See with what great patience, love, and devotion these people have died, how honorably they have resisted the world! . . . They are holy martyrs of God."

In spite of intercession the Anabaptists at Alzey were executed, the men by beheading and the women by drowning. The exact number of the victims cannot be definitely ascertained. Julius Lober's martyr list mentions fourteen in Alzey, three in Heidelberg, and five in Bruchsal. The Hutterite chronicles give 350 as the total number of martyrs in the Palatinate, based on reports of refugees who escaped to Moravia and related that the Anabaptists were "taken to their execution like sheep to slaughter." One of the last martyrs was Philipp von Langenlonsheim, executed at Kreuznach in 1529.

After 1529 there were probably no Anabaptist executions in the Palatinate. Michel Leubel, the details of whose trial were recently made public and who was drowned in the Rhein at Speyer in 1533, may have been an exception. The Protestant electors, beginning with Friedrich II, who became a Lutheran soon after assuming the government in 1544, tried to win the Anabaptists back to the state church by kind methods. Under Friedrich II, who was engaged in conflict with Catholicism, Anabaptism seems to have been firmly implanted in the Palatinate. Hutterite missioners in the second half of the century induced many Anabaptists to go to Moravia, where the brotherhood was enjoying its Golden Age. In the congregations at Worms and Kreuznach serious differences arose concerning doctrine and discipline. The courts were constantly troubled by the property left by the fugitives; in spite of emigration there were continued reports of the spread of the movement.

The church inspection ordered by Otto Heinrich under the Superintendent of Strasbourg, Johann Marbach, confirmed these reports. It was discovered that Anabaptism was strongest where there was a lack of intelligent preachers of the Gospel. Thereupon the pastors were urged to learn what the erroneous articles of the sects were and to counter them in the pulpit, not with noise and derogatory words but with gentleness and honesty; this would be better than prematurely to threaten these people with severe punishment, for they were otherwise honorable, decent, and obedient. However, they should not be allowed to hold official positions, and their dead should be denied a funeral sermon and ringing of the bells.

Upon the request of the Anabaptists a disputation was held at Pfeddersheim in 1557, in which over forty Anabaptists, including nineteen Vorsteher, took part. The questions debated concerned infant baptism, government office, the oath, the reason for their leaving the state church, communion, and the ban. The church declared the Anabaptists defeated; but the Anabaptists persisted in their convictions. Soon after this some important Lutheran and Catholic theologians held a disputation at Worms and came to an agreement, not concerning the treatment of Zwinglians and Sacramentists, but on the "condemnation of the Anabaptists." Thereupon Otto Heinrich issued a severe mandate against the Anabaptists, threatening them with expulsion and punishment according to imperial decree; it was, however, not strictly enforced. Instead, the peaceful Anabaptists were tacitly allowed to stay in the country.

Under the Calvinist Friedrich III, Anabaptism became still more firmly entrenched in the Palatinate. Friedrich was attacked by both the Catholics and the Lutherans; he was blamed for the presence of the Anabaptists in his country. But he continued his practice of trying to convert them by conversations with clergymen. Leonard Dax, a Hutterite missioner, described a conversation of this kind in his pamphlet, Ein pfälzisches Colloquium mit einem Wiedertäufer im Jahre 1567. Hutterites caught in the Palatinate were generally released. The generosity of the rulers was truly amazing for that time. Duke Johann Casimir wrote to Friedrich III on 1 January 1566, that since the beginning pious Christians have often been persecuted as sectarians although they were the best Christians and taught and defended the truth.

This was the frame of mind that led Friedrich III to institute the Frankenthal disputation in 1571. Foreign, refugee, and native Anabaptists were invited to participate and guaranteed safe conduct for two weeks before and after the debate. To the elector's annoyance, only fifteen Anabaptists announced their coming, including several Swiss Brethren and two Hutterites, but no Dutch Mennonites, whom the elector had particularly meant to attract. The Anabaptist spokesman was Diebold Winter of Wissembourg, Alsace. The representative of the Palatinate Anabaptists was Rauff Bisch of Odernheim. For the established church Peter Dathenus, the court chaplain at Heidelberg, was the spokesman, with six other theologians, some of whom came from the Netherlands. The debate lasted nineteen days, from 28 May to 19 June, with two sessions daily beginning at 6 a.m. and 2 p.m. The elector appeared in person for the opening, and kept himself informed of the course of the debate. He inspected the final record, which was then published as a book of 710 pages, in two editions and in a Dutch translation. The debate dealt with the following subjects: the Scriptures, God, Christ, original sin, churches, justification, the resurrection of the body, marriage, community of goods, government, the oath, baptism, and communion. Inexperienced in dogmatic speculation and disputation, Rauff Bisch made the comment, characteristic of the Anabaptists, "It almost seems to us that you are asking us about matters that are too high for us; for we know nothing else to say about them than what the text simply says." Agreement was reached on very few points. The superintendents were to continue to try to convert the Anabaptists, though these attempts were rarely successful.

The lot of the Palatine Mennonites became harder under the son of Friedrich III, the Lutheran Elector Ludwig VI, 1576-1583, who also took sharp measures against the Calvinists. He began to expel the Anabaptists from the country, confiscate their goods to be kept under curators. If an Anabaptist let himself be persuaded to accept the state church, he received his property back after an examination by the superintendent. The superintendents and the pastors were reminded by an "electoral instruction" of 1 August 1579, "to refute Anabaptist errors clearly from the pulpit frequently and to explain thoroughly the practice and benefits of the sacraments." Obstinate Anabaptists were to be imprisoned in the tower on bread and water, but were to be instructed both within the prison and outside several times, "that they may be moved to real conversion." In cases of continued persistence they were to be expelled from the country; this also happened to the Calvinists, one of whom was called "almost an Anabaptist."

Upon the early death of Ludwig VI his brother Johann Casimir succeeded to the government, 1583-1591, who continued his Reformed father's church polity. His brother's Anabaptist mandate was once more proclaimed, but not strictly enforced. It was opposed by the government officials rather than the clergy. The burgrave of Alzey reminded the government that the state cannot be governed exclusively on confessional lines, but that political and economic principles must also be considered. The government once more urged the church council to conduct another disputation, but was refused on the ground that the others had been fruitless. Thereupon the church council issued a general order to all the inspectors who had to deal with Anabaptists. The pastors were doubtful of results, for the Anabaptists would, as one of them said, "see nothing in the members of the church but what will hurt them in their hearts and will cause horror and disgust, namely, an unrestrained Epicurean life with cursing, swearing, overeating, drinking, dancing, quarreling, fighting, scolding, fornication, immorality, and the like." In fact the Anabaptists kept replying, "One could read God's Word also outside the churches, since the people who go to church are very wicked." Many a pastor had to work hard with these Anabaptists. One complained that he had "become hoarse and almost sick."

The youthful Elector Friedrich IV, 1592-1610, like his uncle wanted peace in church affairs. When complaints were heard about new inroads by Anabaptism, he ordered in 1596 to devote greater care to their conversion. The church councillors, on the other hand, demanded severer proceedings by the government. One week later, 29 June 1596, appeared the order of the councillors, that the Anabaptists were to be strictly watched, "although the pastors of all the villages shall on their part neglect nothing of their constant and zealous instruction and admonition."

By the turn of the century, in spite of oppression and emigration to Moravia, Anabaptism had increased noticeably; for in the Catholic and Lutheran vicinity of Frankfort, e.g., the bishopric of Speyer and the graviate of Leiningen, it was much more seriously persecuted. At the close of 1600 the Reformed councillors reported that the Anabaptists in Dirmstein, Weisenheim am Sand, Heppenheim an der Wiese, were becoming more established and that at night great numbers of them gathered near Erpolzheim. "When they are ordered to go to church they say they have a large church which has a big roof." In Kriegsheim 66 were reported in 1601. In 1608 it was reported—though later denied—that even the schoolmaster and his son had attended their meeting.

When Friedrich V (the "Winter King," d. 1632) became Palatine elector in 1610 and the Thirty Years' War broke out in 1618, there were still some Anabaptists in the Palatinate. Surprisingly, they were living at the same places that after the war became Mennonite centers; e.g., Kriegsheim near Monsheim, Obersülzen near Grünstadt, Dirmstadt near Frankenthal, Rohrbach and Mehlingen near Kaiserslautern, and the Zweibrücken area. There were family names which are still among the Mennonites of the Palatinate; e.g., Herstein, Hüthwohl, and Becker. In the last Anabaptist documents before the Thirty Years' War the church councillors raised serious complaint about the increase in the number of Anabaptists in the district of Alzey. It can certainly be assumed that a number of Mennonite families maintained themselves in the Palatinate throughout the war, and then joined the immigrant Mennonites.

From the immigration of Swiss Mennonites from the middle of the 17th century until the reorganization of the Palatinate ca. 1800

During the Thirty Years' War the Palatinate was almost completely depopulated and devastated. The number of Reformed clergymen had been reduced to one tenth of its former number by murder, flight, and emigration. Elector Karl I Ludwig, 1648-1680, called back the surviving ones. The repopulation of his lands was a serious concern to him. He was generous not only to the Lutherans and Catholics, but also to the Mennonites. He admitted a number of Moravian Hutterite families to Mannheim in 1655, who established a small Bruderhof here, which Duchess Elizabeth Charlotte of Orleans, the elector's daughter, recalled in her letters written in 1718. Soon after the war a Mennonite congregation assembled in Mannheim, to whom the elector assigned space for a meetinghouse. He was especially interested in experienced settlers who could rebuild the country. Thus he also admitted the Mennonites expelled from other countries.

One of the first groups to settle in the Palatinate after the Thirty Years' War came from Transylvania. After severe oppression several of these families emigrated and in 1655 settled in Kriegsheim, Osthofen, Harxheim, Heppenheim an der Wiese, and Wolfsheim near Worms. Among them were such family names as Schuhmacher, Kolb, Rohr, and Bonn. Some had become Quakers by 1665; e.g., the Schuhmacher family in Kriegsheim.

The state church was, however, less tolerant than the elector. Already in 1654 voices are heard complaining "about the offensive confusion with the Anabaptists, who despise proper church services and the holy sacraments, let their children run about un-baptized, hold their services boldly in the forests, and even solemnize marriages." From this time on, the church senate continued to warn the government that "it is a necessity to stem the obstinate, fanatical stubbornness of such people and bring them under the discipline of the Reformed Church, marriage, baptism, etc."

In spite of all obstacles the Mennonites made efforts to preserve official toleration and recognition from the elector. In the Palatinate to the right of the Rhine, where also some Anabaptist remnants had been preserved since the 16th century, two Mennonites, Hans Mayer and Hans Körber, decided in 1653 to present a petition to the elector in the name of the congregation, in which they called themselves "Mennists," to obtain permission to meet for worship like their brethren on the left side of the Rhine. But it took a decade, besides the intervention of influential Quakers and even the intermediation of the King of England before Karl I Ludwig was willing to grant them a limited religious freedom. Finally on 4 August 1664, after much effort, they obtained the important general concession that permitted them to meet in groups of more than twenty; but they were forbidden to admit non-Mennonites to the meetings. In return they had to pay an annual fee of six guilders per person as "Mennist Recognition Money," a considerable tax, which was later doubled. Nevertheless this concession was considered a great privilege, meetings having been completely prohibited in 1661. A limit of 200 families was set for the total Mennonite population.

The Mennonites in the Palatinate were increased in number in 1671-1672 when persecution in Switzerland reached its climax. The refugees were received as brethren by the Palatine Mennonites and were given generous support from the Dutch Mennonites, who had already intervened in Switzerland for their toleration. On 2 November 1671, Jakob Everling, the preacher of the Obersülzen congregation, reported that 200 persons had come to the Palatinate, some of whom were cripples, old people of 70-90 years, and families of eight to ten children. They arrived destitute with their bundles on their backs and their children in their arms. In January 1672, 215 persons had arrived west of the Rhine and 428 east of the Rhine. The influx of single families and groups continued into the 18th century. Especially in 1709-1711 many Mennonite families came from Alsace and Switzerland. Thus the numerous small congregations still existing in the Palatinate were established.

By the end of the 17th century new difficulties overwhelmed the new settlers; economically by the French invasion under Louis XIV, ecclesiastically by the Catholic reaction under the electors of the Zweibrücken-Neuburg line which replaced the Protestant Simmern line. In 1674 and 1689 large areas and numerous towns of the Palatinate were devastated, causing serious losses to many Mennonites. Elector Philip Wilhelm, 1685-90, who had renewed the Mennonite concession in 1686, died as a fugitive in Vienna. His strictly Catholic son and successor, Johann Wilhelm, 1690-1716, was very slow to renew the concession; it was finally granted in 1698 after many petitions, and demanded high protection fees. The early years of his reign saw the expulsion of the Mennonites from Rheydt in 1694, which caused consternation in the entire Protestant world, and also the emigration of a group of Mennonites from Ibersheim to Friedrichstadt in Schleswig-Holstein in 1693.

The first emigration of Palatine Mennonites to North America also occurred at the close of the 17th century. In 1685 a Quaker who had previously been a Mennonite, Peter Schumacher of Kriegsheim near Worms, immigrated to Germantown, Pennsylvania. In the spring of 1707 the Kolb brothers — Martin, Johannes, Jakob, and Heinrich — emigrated. Martin Kolb, who settled at Skippack, was one of the first Mennonite preachers in America. He was probably the instigator of further Mennonite emigration, which increased rapidly under Elector Karl III Philip, 1716-1742, for he doubled their protection fees, limited their right to purchase land, seeking thus to prevent the number of Mennonite families in the Palatinate to rise above 200. In the spring of 1717 some 300 Palatine Mennonites were in Rotterdam to embark for Pennsylvania where religious liberty was unrestricted; they received financial support from the Dutch Mennonites. With this group a stream of German immigration set in which continued almost without interruption until the second half of the 19th century. By 1732, 3,000 Palatine Mennonites had arrived in America. By 1773 the immigration lists showed over 30,000 Palatine names, mostly non-Mennonite. The Mennonites in America of Palatine origin numbered c150,000 souls in 1935, of whom 35,000 were living in Lancaster County alone.

A change in favor of the Mennonites took place during the long rule, 1742-99, of the enlightened Karl Theodor of the house of Pfalz-Sulzbach. Although he was Catholic, he granted extensive liberties to the Lutherans, Reformed, Mennonites, and Jews. The concession to the Mennonites was renewed on 27 November 1743, and the protection fee reduced to six guilders. In return the Mennonites advanced the sum of 10,000 guilders toward the election and coronation expenses. Nevertheless the government at first still worked toward the reduction of "this daily increasing condemned sect." Later, however, it realized "that no better, more industrious, and competent subjects are to be found, who, with the exception of their religion, their faith, and their error, should serve the members of other faiths as an example in morals as well as in working day and night."

Since that time, about the middle of the 18th century, the Mennonites of the Palatinate achieved a leading position in agriculture. "The most perfect farmers in Germany are the Palatine Mennonites," wrote the State Economist Christian W. Dohm in the Deutsches Museum in 1778. The official of Hilsbach said about them on 21 January 1794, "They are exemplary, industrious, and intelligent farmers. It would be desirable that every farmer would appropriate their good knowledge of agriculture and stock raising." Jung-Stilling, the pious physician and economist, described the family life of David Möllinger of Monsheim as "the highest ideal of agricultural happiness," calling him the "archfarmer of our Palatine country and perhaps of the Holy Roman Empire," and his friend and brother.

About this time the Mennonites of the Palatinate were also given more and more recognition by the Protestant Church, to which Pietism contributed not a little. Gottfried Arnold had already in 1699, in his Unparteiische Kirchen- und Ketzerhistorie, defended the Mennonites. Gerhard Tersteegen, like Jung-Stilling, carried on personal correspondence with the Palatine Mennonites, and called Adam Krehbill, the pastor at Weierhof, "a man according to God's heart." Peter Weber of Hardenberg was a zealous devotee of Pietism.

Now nearly all government restrictions on the Mennonites of the Palatinate were removed. On 20 April 1769, Jakob Hirschler, elder of the Gerolsheim congregation, wrote to Hans van Steen in Danzig, "Although our ruler is Roman Catholic, nevertheless nearly everywhere Catholics, Lutherans, Reformed, Mennonites, and Jews are living side by side. We are permitted to meet openly for worship wherever we wish, also observe baptism and communion and solemnize marriages. Also we bury our dead openly, and funeral addresses are held, often with many hearers, as in other religions."

At this time the first Mennonite meetinghouses were built in the Palatinate—Weierhof 1773, Sembach 1777, Eppstein and Friedelsheim 1779. The rulers willingly gave their consent, although they stipulated that the church must have the external appearance of a farm building. The names and membership of the congregations are given by Jakob Hirschler for 1769 as follows: "Erpolzheim and Friedelsheim 140, Spitalhof 45, Ruchheim 26, Alsheim and Ibersheimerhof 120. Oberflörsheim and Spiesheim 100, Kriegsheim 52, Wartenberg and Sembach 250, Weierhof 90, Rheingrafenstein 32, Rödern and Schafbusch 45, Böchingen 68, Zweibrücken 94, Gerolsheim, Obersülzen, and Heppenheim 112, Höningen 54, Eppstein-Friesenheim-Mannheim" (no figures given, but "some 20 households" given for Mannheim). In addition there were numerous scattered Amish families living in the Palatinate around Zweibrücken and Ixheim.

All the congregations were served by lay elders and preachers from their own midst. In 1770 these were: "Abraham Oellenberger in Gönnheim; Daniel Staufler in Guntersblum; Christian Weber in Oberflörsheim; Johannes Krehbiel in Wartenberg; Jakob Galle in Erbesbüdesheim; Daniel Hirschler, Geisberg; Johannes Schnebele for Zweibrücken; Jakob Hirschler, Gerolsheim; Martin Möllinger, Mannheim." Toward the end of the century a lack of qualified voluntary preachers was painfully felt here and there. The men who had been chosen refused the office. "This error, which may be called disobedience, is unfortunately making serious inroads into the Palatinate," wrote Elder Lorenz Friedenreich of Neuwied on 27 February 1775. Therewith a new development began for the Palatine Mennonites.

Shortly before and after the turn of the century two groups of Palatine Mennonites emigrated. In 1784, 28 Mennonite families followed the invitation of Emperor Joseph II to settle in Galicia, where they made three settlements near Lemberg-Einsiedel, Falkenstein, and Rosenberg. In 1802 eight families settled in Donaumoos in Bavaria. Other Palatine and Alsatian Mennonites followed, until there were twenty-five families, twelve of whom were living in Maxweiler, which they had founded, and thirteen in the surrounding villages. About the middle of the 19th century most of them immigrated to America.

From the beginning of the freedom of the 19th century to the present

From 1792 until 1813 the Palatinate to the left of the Rhine was under French rule. In 1801 the Kurpfalz was dissolved in the Treaty of Lunéville. After Napoleon's defeat, 1814 f., a large part of the Palatinate on the left of the Rhine fell to Bavaria, a smaller part, Rhenish Hesse, to Hesse-Darmstadt. The part right of the Rhine fell for the most part to Baden, and a smaller part to Hesse-Darmstadt. With the French occupation in 1803 all the limitations on Mennonite freedom, legal, economic, and ecclesiastical, were removed.

Equality of citizenship was gratefully accepted by the Mennonites. But at the same time the leaders feared that this equality of citizenship would lead to complete conformity to their surroundings and the loss of the old doctrines. This concern is clearly seen in the Ibersheim Decisions of 1803 and 1805, in which the Mennonites of the Palatinate and of all South Germany expressly endorsed the old Mennonite principles, such as adult baptism, separation from worldly living, and nonresistance. Because soon afterward nonresistance was nonetheless lost, Wilhelm Mannhardt called these Decisions, with some justification, "the evening glow in the sky of orthodox Mennonitism in the Rhineland."

Actually about the turn of the century Palatine Mennonitism underwent a radical change in development that was to give it its characteristic stamp within German Mennonitism. The first element was the sacrifice of the lay ministry, which was maintained only in a few small congregations in the south: Branchweilerhof near Neustadt and Deutschhof-Geisberg near Bergzabern, which then joined the Verband. The small congregation of Altleiningen in the heart of the Palatinate almost lost its existence on this account, even though in 1811, under its preacher Christian Goebels (d. 1821), it built its own church. J. Schiller (1812-1886) published in Pfälzer Memorabile an interesting account of a visit to this church; he had come in order to hear a sermon by a Mennonite lay preacher, but unprepared as he was he was compelled to preach, and thereby changed his whole concept of preaching. The last important lay preachers in the Palatinate were Valentin Dahlem, the initiator of the Ibersheim Decisions and editor of a formulary, Johannes Goebels of Hertlingshausen near Altleiningen, and Heinrich Koller of Kuhbörncheshof.

As the need for preachers in the Palatine congregations increased they began to call theologically trained and professional ministers from their own ranks or from the outside. In 1819 Leonhard Weydmann came from Krefeld to Monsheim to gather and re-establish the congregation. He was followed in Monsheim by Johannes Molenaar, also from Krefeld, 1836-1868. In Sembach Johannes Risser of Friedelsheim, 1832-1868, led the congregation to a new flowering. On the Weierhof Hermann Reeder of Neuwied was called, who had attended a Baptist seminary in England. Friedelsheim found two pastors in its own membership—the teacher Jakob Ellenberger 1827-1879, followed by his nephew with the same name. Ibersheim called preachers from West Prussia—Bernhard Thiessen, 1843-1856; then Heinrich Neufeld, 1856-1869. Under the ministry of these men new catechisms appeared in 1841, 1854, and 1861; a new hymnal in 1854, 1876; a minister's manual in 1852. Michael Loewenberg, minister at the Weierhof 1849-1874, founded a school there in 1867, which later became the Realanstalt am Donnersberg; it was planned as a ministerial training school, but became a secondary school.

The engagement of professional ministers or pastors, most of whom were educated in Protestant seminaries or universities, denoted a deviation from Mennonite tradition, but proved itself as useful for the preservation of Palatine-Hessian Mennonitism. Externally this led to an era of church building. Meetinghouses, still in use, were built at Monsheim in 1820, Ibersheim 1836, Weierhof 1837, and Friedelsheim 1838. In 1853 the small church in Sembach built in 1777 was torn down and replaced by a larger church. The Kühbörncheshof congregation, which belonged to Sembach until 1832, built a meetinghouse in that year. In 1842, 1843, and 1847 churches were built in Deutschhof, Ernstweiler, and Ixheim, the last named being an Amish congregation which did not unite with the others until 1937 and then met with them at Zweibrücken; both churches were abandoned. In the second half of the century churches were built at Obersülzen in 1866, Neudorferhof 1885, and Kohlhof 1888; in 1903 the church at Ludwigshafen was built, but was razed in 1958 for the rebuilding of the city.

Since 1824 the Conference of the Palatine and Hessian Mennonite Churches has been meeting more or less regularly in annual sessions, which have greatly strengthened the cohesion of the group. The Conference established a relief fund which was later (1886) called the Mennonitische Hilfskasse. Since 1885 most of the congregations have also belonged to the Vereinigung. The congregations fall into six groups, each of which is served by one pastor. The groups, with 1958 membership, are composed as follows: (1) Kaiserslautern 72, Kühbörncheshof 163, Zweibrücken 200; (2) Sembach 250, Enkenbach 270, Neudorferhof 196; (3) Weierhof 445, Uffhofen 48, Eisenberg; (4) Monsheim 255, Obersülzen 94, Biedesheim; (5) Ibersheim 165, Eppstein 110, Ludwigshafen 90; (6) Friedelsheim 151, Kohlhof 64, Atleiningen 30.

Leading ministers since just before the turn of the century were "Christian Neff, at Weierhof, 1887-1946; Thomas Löwenberg, Ibersheim, 1883-1917; Abraham Hirschler, Kaiserslautern, 1880-1930; Johannes Hirschler, Monsheim, 1899-1926; Matthias Pohl, Sembach, 1901-1929; Johannes Foth, Friedelsheim, 1904-1957." In the Palatinate and Hesse there were some 3,200 Mennonites in the mid-1950s. This figure includes some 1,000 refugees from West Prussia who came to the Palatinate after 1948 and were kindly received by the brethren. A congregation of this kind had arisen at Enkenbach near Kaiserslautern since 1951 with some 270 members including the residents in the Mennonite Home for the Aged, Friedenshort. In 1957 this congregation received a meetinghouse, which, like the entire settlement, was built with substantial aid from German and American brethren. In Kaiserslautern the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) built the "Mennonite House" in 1956, in which the resident congregation held its meetings. In Bad Dürkheim the MCC for years supported a children's home. In Ludwigshafen the Relief Work of the Vereinigung had its center. The active work of these organizations contributed greatly to the strengthening and revival of Palatine-Hessian Mennonitism as well as German Mennonitism as a whole after World War II.

Bibliography

Crous, Ernst. "Mennoniten im Regierungsbezirk Trier 1827-1870." Mennonitischer Gemeinde-Kalender (1940): 62-73.

Crous, Ernst. "Wie die Mennoniten in die deutsche Volksgemeinschaft hineinwuchsen." Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter (1939): 13-24 (repr. Karlsruhe, 1939).

Hege, Christian. Die Täufer in der Kurpfalz. Frankfurt, 1908.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. II, 588-600 (Kurpfalz), 356-577 (Pfalz-Zweibrucken), 357-59 (Pfälzische Kirchenordnungen), 492-94 (Rheinland-Pfalz); v. III, 490 f.

Hein, Gerhard. "The Development of the Mennonite Hof of the Seventeenth Century Palatinate into the Mennonite Churches of Pfalz Rheinland Today." Mennonite Quarterly Review (1955): 188-96.

Hein, Gerhard. "Unsere Gemeinden in der Pfalz vor 200 Jahren und heute." Der Mennonit IX (1956): 138-40, 154 f., 170 f.

Hoop Scheffer, Jacob Gijsbert de. Inventaris der Archiefstukken berustende bij de Vereenigde Doopsgezinde Gemeente to Amsterdam, 2 vols. Amsterdam: Uitgegeven en ten geschenke aangeboden door den Kerkeraad dier Gemeente, 1883-1884: v. 1, Nos. 1009, 1059, 1130, 1196-99, 1248 f., 1319, 1405-7, 1409, 1414, 1420-26, 1428 f., 1438, 1458, 1470-73, 1476-83, 1495, 1498-1504, 15101, 1515, 1517, 1519, 1531 f., 1539, 1750 f., 1866 f., 1881, 2256, 2260, 2267, 2274; v. 2, Nos. 686-90.

Krebs, Manfred. "Beiträge zur Geschichte der Wiedertaufer am Oberrhein." in Zeitschrift für die Geschichte des Oberrheins LXXXIII (1931): 567-76.

Krebs, Manfred. Quellen zur Geschichte der Täufer. IV. Band, Baden and Pfalz. Gütersloh: C. Bertelsmann, 1951.

Müller, Ernst. Geschichte der Bernischen Täufer. Frauenfeld: Huber, 1895. Reprinted Nieuwkoop : B. de Graaf, 1972.

Naamlijst der tegenwoordig in dienst zijnde predikanten der Mennoniten in de vereenigde Nederlanden. Amsterdam, 1731, 1743, 1755, 1757, 1766, 1769, 1775, 1780, 1782, 1784, 1786, 1787, 1789, 1791, 1793, 1802, 1804, 1806, 1808, 1810, 1815, 1829.

Namensverzeichniss.

Schowalter, Paul. "Der Kirchenbau in den Mennonitengemeinden von Pfalz-Hessen." Mennonitischer Gemeinde-Kalender (1953): 36-44.

| Author(s) | Gerhard Hein |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1959 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Hein, Gerhard. "Palatinate (Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1959. Web. 27 Nov 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Palatinate_(Rheinland-Pfalz,_Germany)&oldid=143691.

APA style

Hein, Gerhard. (1959). Palatinate (Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 27 November 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Palatinate_(Rheinland-Pfalz,_Germany)&oldid=143691.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 4, pp. 106-112, 1147. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.