Civilian Public Service

Civilian Public Service (CPS) was a plan of service provided under the United States Selective Service and Training Act of 1940 for conscientious objectors who were unwilling to perform any kind of military service whatsoever. In the six and one-half years that men were drafted under this law, nearly 12,600 young men were assigned to Civilian Public Service camps to perform "work of national importance." Of these, 4,665 or 38 per cent were Mennonites. At least 86 other sects and denominations had three or more men each in CPS camps. Following the Mennonites in number of men in the camps were the Church of the Brethren, Friends, and the Methodists, who ranked second, third, and fourth respectively.

During World War I, American conscientious objectors were actually drafted into the army, where they were expected to perform noncombatant service. The refusal of large numbers of these men to wear the military uniform or to engage in work connected with the military produced difficult problems for the army as well as for the young men who were placed under pressure to do that which their consciences forbade, and led to a more liberalized program during World War II. When in 1940 legislation for a draft law was being considered in Congress, the historic peace churches as well as other denominations presented their desire for a more liberal program to the proper authorities, with the result that the law finally passed was superior to former ones in four respects. The basis for objection was broadened to include all of those who by reason of religious training and belief could not participate in war. When a local draft board refused the classification a registrant desired, he was given the right of appeal under the new law. Perhaps most important was the new provision for assignment, in lieu of induction into the army, to work of national importance under civilian direction. The fourth improvement was placing conscientious objectors under civilian control and making violations of the law subject to the Federal courts rather than military courts.

These gains were in part the result of inter-church cooperation of the Historic Peace Churches, Brethren, Friends, and Mennonites, in the period between the two wars, when representatives of these groups met occasionally to consider their problems and to come to a common mind concerning the kind of program they would desire for conscientious objectors. Among the most important of these conferences was the one held at Newton, Kansas, in 1935, when a "Plan of Unified Action in Case the United States Is Involved in War" was adopted. This called for a program of alternative civilian service in lieu of service in the armed forces.

Out of this cooperative effort came also the National Council for Religious Conscientious Objectors, later known as the National Service Board for Religious Objectors, which represented not only the Historic Peace Churches but also many other denominations to the government during World War II. This organization, however, was also the result of government initiative, for as is stated in its official report Conscientious Objection, "These groups (the three Historic Peace Churches) were now desirous also of the privilege of operating work units of conscientious objectors. It was evident that they had rather different ideas than the System for the administration of such units and it was anticipated that misunderstandings and confusion would be the outcome of separate agreements with the several groups. It was therefore suggested that one central representative body be formed through which all matters could be cleared by Selective Service."

The first registration under the new draft law occurred on 16 October 1940, but it was not until 11 April of the following year that the President authorized the establishment and designation of work of national importance for conscientious objectors. In the meantime conscientious objectors who had registered with their local draft boards were placed into class I-A-O if they were willing to accept induction into the army, there to perform noncombatant service, usually in hospital or medical work. Those not willing to accept induction into the army were classified IV-E after they had filled out convincingly "Form 47," which asked questions designed to reveal the sincerity of their position.

In May 1941 the first Mennonite Civilian Public Service camp was opened, near Grottoes, Virginia. The camp consisted of four barrack dormitories, a large dining room, offices, staff quarters, and other buildings, all formerly used by the government for young men engaged in the work of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). During the next several years many such CCC camps were used as the "base camps" for drafted conscientious objectors.

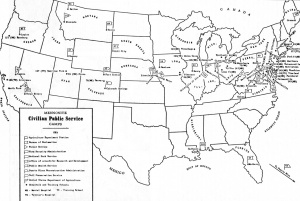

This first Mennonite camp was established to engage in soil conservation. Before the end of Civilian Public Service, 11 soil conservation camps scattered from Maryland to Idaho had been or were being operated by the Mennonite Central Committee, acting for the Mennonites of the United States. Early in the CPS program, it was assumed that since farming was the leading profession among Mennonites, most of the drafted men would prefer this kind of service. When an increasing number of men came from nonfarm backgrounds, other types of work were opened so that by September 1945 only 19 per cent of the Mennonite men were in soil conservation. An equal number, however, were engaged in other forms of agricultural service, including dairy units.

A second type of work was that done under the direction of the United States Forest Service. The first Forest Service camp operated by the Mennonite Central Committee was the one at Marietta, Ohio, which opened in June 1941. Others were operated in Indiana, Montana, and California, a total of six. Although the major purpose of the western camps was to prevent or stop forest fires, much time was spent in building forest trails, caring for nursery stock, and engaging in pest control. One of the most spectacular services was that of the parachute jumpers who were trained to parachute to the scene of a forest fire there to engage in the usual fire-fighting techniques.

Four MCC camps, located in Virginia, Montana, and California, were under the National Park Service. In 1945 approximately 10 per cent of the men in Mennonite camps were in this work. Various types of maintenance work as well as fire fighting in national parks were performed by these men. The two camps under the Bureau of Reclamation worked on the construction of dams and a third camp divided its work between this Bureau and the Farm Security Administration, developing an irrigation project in the Yellowstone River Valley.

Other service in the field of agriculture was performed in small units such as the one at the Nebraska Agricultural Experiment Station. A Civilian Public Service Reserve was made up of men who acted as livestock attendants on boats of cattle and horses sent to Europe. In May 1942 the first group of men from a Mennonite camp to serve in a dairy unit were placed in Wisconsin. By August 1945 the Mennonites had over 550 men in dairy work, among whom were a considerable number engaged in dairy herd testing.

Of an entirely different nature was work in the dangerously undermanned mental hospitals and training schools. In August 1942 the first men from a Mennonite camp to work in a state mental hospital arrived at Western State Hospital, in Staunton, Virginia. By December 1945 more than 1,500 men had served in mental hospital units under Mennonite Central Committee administration. Other men served under the United States Public Health in Florida and Mississippi where the work centered around hookworm control. A unit in Puerto Rico spent part of its time working with the same problem. Receiving much publicity were the "guinea pig" units, in which men working under the Office of Scientific Research and Development subjected themselves to various experiments designed to gain information having to do with nutrition and disease.

The camps and units operated either individually by the MCC or jointly with another church agency are given below in order of establishment.

Civilian Public Service Camps

| Camp No. | Camp Name | Location | Operating Group | Technical Agency | Capacity | Date Approved | Date Closed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Grottoes | Grottoes, Virginia | MCC | SCS | 150 | 1941 03 14 | 1946-05-31 |

| 5 | Colorado Springs, CO | MCC | SCS | 165 | 1941-03-14 | 1946-04-12 | |

| 8 | Marietta, OH | BSC-MCC | FS | 50 | 1941-04-19 | 1943-04-30 | |

| 13 | Bluffton, IN | MCC | FS | 150 | 1941-05-07 | 1942-04-08 | |

| 18 | Denison, IA | MCC | SCS | 150 | 1941-08-02 | 1944-10-15 | |

| 20 | Wells Tannery, PA | MCC | SCS | 120 | 1941-08-22 | 1944-10-15 | |

| 22 | Henry | Henry, IL | MCC | SCS | 135 | 1941-11-17 | 1942-11-16 |

| 24 | Hagerstown, MD | BSC-MCC | SCS | 175 | 1941-12-31 | 1946-09-30 | |

| 25 | Weeping Water, NE | MCC | SCS | 275 | 1942-02-11 | 1943-04-30 | |

| 27 | Crestview, FL | BSC-MCC | PHS | 100 | 1942-04-01 | 1946-12-10 | |

| 28 | Medaryville, IN | MCC | FS | 150 | 1941-04-01 | 1946-03-31 | |

| 31 | Camino, CA | MCC | FS | 200 | 1942-04-01 | 1946-12-10 | |

| 33 | Fort Collins, CO | MCC | SCS | 200 | 1942-05-06 | 1946-09-30 | |

| 35 | North Fork, CA | MCC | FS | 200 | 1942-05-20 | 1946-02-28 | |

| 39 | Galax, VA | MCC | NPS | 150 | 1942-05-23 | 1943-05-17 | |

| 40 | Howard, PA | MCC | SCS | 100 | 1942-05-27 | 1943-04-30 | |

| 43 | San Juan, PR | BSC-MCC | PRRA | 75 | 1942-06-20 | 1947-03-31 | |

| 44 | Western State Hospital | Staunton, VA | MCC | SMH | 56 | 1942-07-15 | 1946-09-01 |

| 45 | Luray, VA | MCC | NPS | 150 | 1942-07-27 | 1946-06-30 | |

| 52 | Powellsville, MD | MCC-FSC | SCS | 175 | 1942-08-25 | 1947-03-31 | |

| 55 | Belton, MT | MCC | NPS | 200 | 1942-09-07 | 1946-09-30 | |

| 57 | Hill City, SD | MCC | BR | 200 | 1942-090-23 | 1946-02-28 | |

| 58 | Farnhurst, DE | MCC | SMH | 40 | 1942-09-18 | 1946-11-15 | |

| 60 | Lapine, OR | MCC | BR | 300 | 1942-10-07 | 1943-12-31 | |

| 63 | Marlboro, NJ | MCC | SMH | 65 | 1942-11-05 | 1946-12-10 | |

| 64 | Terry, MT | MCC | SCS-FSA | 100 | 1942-11-10 | 1946-06-30 | |

| 66 | Norristown, PA | MCC | SMH | 95 | 1942-11-05 | 1946-10-31 | |

| 67 | Downey, ID | MCC | SCS | 150 | 1942-11-07 | 1945-12-31 | |

| 69 | Cleveland, OH | MCC-FSC | SMH | 30 | 1942-11-26 | 1946-09-30 | |

| 71 | Lima State Hospital | Lima, OH | MCC | SMH | 12 | 1942-11-26 | 1946-09-30 |

| 72 | Macedonia, OH | MCC | SMH | 20 | 1942-11-26 | 1946-10-01 | |

| 77 | Greystone Park, NJ | MCC | SMH | 95 | 1943-01-06 | 1946-10-31 | |

| 78 | Colorado Psychopathic Hospital | Denver, CO | MCC | SMH | 15 | 1943-01-07 | 1946-03-25 |

| 79 | Provo, UT | MCC | SMH | 25 | 1943-01-16 | 1946-04-30 | |

| 85 | Howard, RI | MCC | SMH | 60 | 1943-01-29 | 1946-11-19 | |

| 86 | Mount Pleasant State Hospital | Mount Pleasant, IA | MCC | SMH | 33 | 1943-02-01 | 1946-10-01 |

| 90 | Ypsilanti, MI | MCC | SMH | 75 | 1943-03-04 | 1946-10-05 | |

| 92 | Vineland, NJ | MCC | STS | 16 | 1943-03-16 | 1946-06-14 | |

| 93 | Harrisburg, PA | MCC | SMH | 35 | 1943-03-20 | 1946-08-24 | |

| 97 | Dairy Farm Project | | Co-op | DA | | 1943-04-09 | 1946-10-31 |

| 97.01 | San Joaquin County | California | MCC | | 40 | 1943-04-01 | 1946-08-21 |

| 97.02 | Colorado | MCC | | 25 | 1943-04-01 | 1946-08-31 | |

| 97.05 | Worchester County | Massachusetts | MCC | | 20 | 1945-02-28 | 1946-11-22 |

| 97.09 | Queen Annes County | Maryland | MCC | | 20 | 1945-02-01 | 1946-10-12 |

| 97.10 | Genesee County | Michigan | MCC | | 20 | 1943-05-01 | 1946-10-30 |

| 97.11 | Lenawee County | Michigan | MCC | | 20 | 1943-04-01 | 1946-09-16 |

| 97.12 | Hillsborough County | New Hampshire | MCC | | 20 | 1945-02-28 | 1946-09-18 |

| 97.19 | Cuyahoga County | Ohio | MCC | | 13 | 1943-04-01 | 1946-06-19 |

| 97.20 | Lorain County | Ohio | MCC | | 2 | 1943-04-01 | 1946-04-08 |

| 97.21 | Summit County | Ohio | MCC | | 20 | 1943-04-01 | 1946-08-23 |

| 97.22 | Ohio | MCC | | 25 | 1943-04-01 | 1946-03-01 | |

| 97.24 | Tillamook County | Oregon | MCC | | 20 | 1945-06-01 | 1946-09-18 |

| 97.25 | Allegheny County | Pennsylvania | FSC-MCC | | 10 | 1943-04-01 | 1946-10-23 |

| 97.26 | Pennsylvania | MCC | | 20 | 1943-05-01 | 1946-10-23 | |

| 97.28 | York County | Pennsylvania | MCC | | 20 | 1943-04-01 | 1946-06-22 |

| 97.29 | King County | Washington | BSC-MCC | | 15 | 1943-04-01 | 1946-05-27 |

| 97.30 | Dane County | Wisconsin | MCC | | 20 | 1943-04-01 | 1946-08-30 |

| 97.31 | Dodge County | Wisconsin | MCC | | 20 | 1942-05-01 | 1946-09-18 |

| 97.32 | Fond du Lac County | Wisconsin | MCC | | 20 | 1943-04-01 | 1946-09-12 |

| 97.33 | Green County | Wisconsin | MCC | | 20 | 1943-04-01 | 1946-06-26 |

| 97.34 | Outagamie County | Wisconsin | MCC | | 20 | 1943-04-01 | 1946-08-28 |

| 100 | Dairy Herd Testing | | Co-op | DA | | | |

| 100.5 | Iowa | Iowa | MCC | | 13 | 1943-08-01 | 1946-06-28 |

| 100.6 | Maine | Maine | MCC | | 17 | 1943-11-01 | 1946-09-28 |

| 100.8 | Michigan | Michigan | MCC | | 52 | 1943-05-01 | 1946-08-21 |

| 100.11 | Pennsylvania | Pennsylvania | MCC | | 68 | 1943-03-01 | 1946-09-23 |

| 103 | Huson, MT | MCC | FS | 250 | 1943-04-24 | 1945-12-31 | |

| 106 | Lincoln, NE | MCC | EXS | 40 | 1943-05-04 | 1946-10-16 | |

| 107 | Three Rivers, CA | MCC | NPS | 150 | 1943-05-05 | 1946-05-31 | |

| 110 | Allentown State Hospital | Allentown, PA | MCC | SMH | 25 | 1943-05-31 | 1946-05-13 |

| 115 | Office of Scientific Research and Development | Various places | Co-op | OSRD | | 1943-08-31 | 1946-12-31 |

| 117 | Lafayette, RI | MCC | STS | 15 | 1943-10-29 | 1946-09-01 | |

| 118 | Western State Hospital | Wernersville, PA | MCC | SMH | 25 | 1943-11-03 | 1946-06-27 |

| 120 | Kalamazoo, MI | MCC | SMH | 30 | 1943-11-03 | 1946-06-22 | |

| 122 | Winnebago, WI | MCC | SMH | 15 | 1943-11-08 | 1946-02-28 | |

| 123 | Union Grove | Union Grove, WI | MCC | STS | 25 | 1943-11-08 | 1946-08-20 |

| 125 | Orono, ME | MCC | EXS | 10 | 1943-11-22 | 1946-05-15 | |

| 126 | Beltsville Research | Beltsville, MD | MCC | EXS | 35 | 1943-11-29 | 1946-12-31 |

| 127 | American Fork, UT | MCC | STS | 15 | 1943-11-30 | 1946-01-10 | |

| 138 | Lincoln, NE | MCC | SCS | 85 | 1944-09-11 | 1946-10-15 | |

| 140 | Office of the Surgeon General | Various places | Co-op | SGO | | 1944-12-18 | 1946-12-10 |

| 141 | Gulfport, MS | MCC | PHS | 40 | 1944-01-17 | 1946-12-10 | |

| 142 | Woodbine | Woodbine, NJ | MCC | STS | 20 | 1944-01-17 | 1946-09-30 |

| 143 | Catonsville State Hospital | Catonsville, MD | MCC | SMH | 35 | 1945-01-22 | 1946-08-15 |

| 144 | Poughkeepsie, NY | MCC | SMH | 30 | 1945-03-06 | 1946-03-30 | |

| 146 | New York State Experiment Station | Ithaca, NY | MCC | EXS | 6 | 1945-04-05 | 1946-06-24 |

| 147 | Tiffin, OH | MCC | STS | 25 | 1945-04-25 | 1945-11-12 | |

| 150 | Livermore, CA | MCC | VAH | 130 | 1945-11-13 | 1946-12-10 | |

| 151 | Roseburg, OR | MCC | VAH | 40 | 1945-12-18 | 1946-12-10 |

Operating Groups

- BSC - Brethren Service Committee

- Co-op - Coopeartive by all religious agencies

- MCC - Mennonite Central Committee

- BR - Bureau of Reclamation

- DA - Department of Agriculture

- EXS - Extension Service, U.S.D.A.

- FS - United States Forest Service

- FSA - Farm Security Administration

- NPS - National Park Service

- OSRD - Office of Scientific Research and Development

- PHS - Public Health Service

- PRRA - Puerto Rico Recontruction Administration

- SCS - Soil Conservation Service

- SGO - Surgeon General's Office

- SMH - State Mental Hospital

- STS - State Training School

- VAH - Veterans' Administration Hospital

During the 1941-1947 period of Civilian Public Service, the men assigned to Mennonite camps performed a total of 2,296,175 man-days of service, exclusive of the work in CPS camps numbers 27, 43, 97, and 100, which were operated jointly by two or more agencies. At least 120 different types of work were done according to the Works Progress Reports in the Selective Service Records Offices. As the draftees were not paid for the work performed in the base camps, and only given maintenance wages of $15 per month in the special projects (using the basic army pay of $50 a month for estimation) men in Mennonite CPS contributed approximately $4 million worth of labor to the federal and state governments. The federal government spent approximately $1 1/3 million on CPS. Thus the United States benefited to the figure of $2 2/3 million from the contribution of men drafted to Mennonite CPS camps.

To operate the camps under Mennonite direction, the churches contributed to the Mennonite Central Committee in money and goods a total of over $3 million. Early in the planning for the Civilian Public Service program, the MCC set up a quota system for raising funds to pay for the administration of the program, under which it was suggested that all members of Mennonite churches should contribute 50 cents per member up to 1 August 1941. Other quotas were adopted from time to time so that by the end of Civilian Public Service every Mennonite who had met the suggested quotas had given $21.45. Certain branches of the church contributed more than this amount, while others fell far short of this figure. As the quotas were not mandatory, the MCC made no attempt to compel the churches to give the suggested amounts. Gifts-in-kind contributed by the churches included large quantities of food, particularly canned goods. In addition to the moneys and gifts collected for CPS by the MCC, congregations and individuals gave individual gifts to men in camp. Certain conferences and congregations also gave money payments to their men at the time of their demobilization. The Lancaster Mennonite Conference, for instance, gave each man a gift of $10 per month for the time he had spent in CPS. As many of the drafted men who served without pay in CPS had dependents, the various Mennonite groups were urged to take care of these who were their own members in need. Those cases that were not handled in this manner were dealt with directly by the MCC.

The camps were operated under a system of divided responsibility. Selective Service agreed to "furnish general administrative and policy supervision and inspection, and will pay the men's transportation costs to the camps." The National Service Board for Religious Objectors representing the churches that had large numbers of conscientious objectors agreed for a temporary period "to undertake the task of financing and furnishing all other necessary parts of the program, including actual day-to-day supervision and control of the camps (under such rules and regulations and administrative supervision as is laid down by Selective Service), to supply subsistence, necessary buildings, hospital care, and generally all things necessary for the care and maintenance of the men." This temporary agreement was renewed from time to time, and by the end of the draft the Mennonites were still cooperating in this arrangement, although certain other groups had withdrawn, having come to feel that this contract made them a party with the government in the enforcement of the conscription system and disagreeing with certain regulations of Selective Service which they regarded as being arbitrary.

This dual control of the camps although it may have operated better in Mennonite camps than in some others was the object of much criticism both by camp leaders who felt that the lines of authority were not clearly drawn and by Selective Service officials who felt that the plan interfered with effective discipline. Selective Service, therefore, recommended that in any future program dual control be eliminated in favor of complete government control.

During the early days of Mennonite Civilian Public Service camps, older men, who were usually ministers, were appointed by the Mennonite Central Committee to be camp directors. As the program developed, younger men who were draftees were generally selected, with satisfactory results. To the surprise of many observers, CPS developed a comparatively large number of capable young leaders, who were called upon constantly to make decisions that were perhaps more difficult than those facing the pastor of an average Mennonite congregation. After the close of the program, a large number of these young men were assigned responsible positions in the ministry as well as in other church offices.

The Historic Peace Churches were willing to accept the responsibilities listed above in the agreement with Selective Service because this arrangement gave them the opportunity to follow their men to camp in order to minister to them. The churches not only provided regular religious services for their men but also set up educational programs that included Bible and devotional courses as well as crafts and regular high-school and college courses. In time each Mennonite camp was assigned an educational director who cooperated with the camp manager in organizing and administering a well-arranged program designed to give the camper meaningful and creative experiences during his off-work hours. Courses were taught by camp staff, campers, government staff men, and by church and school leaders who visited the camps regularly.

It was no easy task to provide an adequate spiritual ministry for the men. In the early months of the program, ministers were appointed to the camp directorships but in time it was learned that the administrative work and spiritual ministry in a camp did not belong to the same office. It also became difficult to obtain enough ministers to supply the rapidly increasing number of camps. As a result area pastors were appointed when obtainable and in other cases Mennonite ministers in the nearby states took turns in visiting the camps. This plan worked more satisfactorily in the east than in the west, where travel distances were greater. One of the chief failures of the entire Mennonite Central Committee-Civilian Public Service program was in not supplying enough camp pastors or in not having a large enough number of qualified ministers available for a regular program of services in the camps. In spite of this lack of a well-organized program of spiritual ministry and in spite of the fact that the campers were living under abnormal conditions, away from the sheltering influences of the home community and thrown in with many others whose views on various subjects were novel, the majority of men in a carefully sampled poll of opinion declared that as a result of their CPS experiences they held to the doctrines of their church more strongly than before while another 34 per cent declared that their loyalty had remained the same. Living in close proximity to men from many faiths and environments produced a re-examination of convictions and traditions that on the whole proved wholesome to the majority of men.

CPS created a new respect for the government which granted to CO's a greater amount of religious liberty than had formerly been enjoyed during war-times in the United States. It gave thousands of young men the opportunity to witness to their religious convictions not only by the act of going into CPS but also by the way in which they lived together and in the quality of work which they did. It gave young men an opportunity to build the kind of camp community life that covered all areas of life—physical, social, educational, cultural, spiritual. As there were no traditions or patterns to follow, much experimentation was possible. It widened their knowledge of Mennonitism, it brought about a re-examination of their peace position, it taught them new skills and introduced them to new areas and environments, it taught them and their elders that young people could be trusted to carry responsibility, and it aroused their interest in new areas of service, particularly in mental hospitals and in public health work as well as in conservation.

Many CPS groups organized reunions which met yearly, or less often, after the close of the war. Here friendships were renewed and interests as broad, and broader, than Mennonitism were maintained. Yearly these groups turned their attention away increasingly from their past experiences to the present and future challenges facing nonresistant Christians. Several groups were sponsoring programs of peace education and are engaging in service projects.

On the other hand, the Civilian Public Service program revealed certain weaknesses. Less than half of all drafted Mennonite men chose to go into CPS, averaging the records of those conservative branches in which nearly all drafted men had gone to CPS with the more liberal groups which no longer exercised church discipline on participation in the military, revealing to what degree the historic position of the church on the participation in war had been surrendered. It also revealed that many conscientious objectors had a superficial understanding of their position and had little depth of spiritual experience. Intolerance and lack of love for each other led to tensions among campers. Working without pay and sometimes on jobs that appeared insignificant had a demoralizing effect on many men. It remained to be seen what the long-range effects of conscription on 8,000 young Mennonites would be. Some who witnessed government red tape and inefficiency in certain areas reacted by developing cynicism and a lack of cooperation toward government.

The Mennonite Central Committee on the basis of its experience made certain recommendations for any future program of civilian public service. It suggested that the government should have basic administrative responsibility for administering the draft but should then turn the drafted conscientious objectors over to the church service agencies. They also recommended that in the future the men be given pay and that the program be strictly under the control of civilian agencies of the government in a statement presented to the House Military Affairs Committee in 1945.

The Selective Service System also brought its recommendations in its two-volume report to the President (Conscientious Objection, 1950). Their twelve points are summarized below: (1) any future draft law should make provision "for civilian duty in work of national importance"; (2) the drafted conscientious objector should be given more rights and privileges in the next law, including pay and family allowance; (3) there should be more effective methods of determining the validity of claims for a conscientious objector classification, with more help available from the Justice Department; (4) there should be provisions for immediate and continuous detention of the troublemakers in the camps so that they can not damage the morale of the camp or the reputation of the program; (5) the camp system should be continued but the camp director should be an employee of the agency for which work is being done; (6) those assigned to Civilian Public Service camps should be given the same rigid physical and mental examinations as are given to those assigned to the military; (7) objectors who violate Selective Service laws should be tried by the civil courts but these cases should be given priority; (8) the objector who feels that justice has not been done him should be given a prompt hearing; (9) the objector accused of violations should be allowed to comply with the law during court proceedings; (10) there should be established and applied early "comprehensive statistical and other records and reports on the activities of the System in the field"; (11) there should be a "wide variety of regular projects, manual in nature, and also of special ones, skilled and professional"; and (12) much study should be given by the government to camp organization and administration, the national significance of various projects as well as those overseas, and the most effective use of conscientious objector man power.

See Alternative Service Work Camps for the Canadian camps for conscientious objectors during World War II.

Bibliography

Conscientious Objection. Special Monograph No. 11. Washington, DC: Selective Service System, 1950.

Eisan, L. Pathways of Peace —A History of the Civilian Public Service Program Administered by the Brethren Service Committee. Elgin, IL: Brethren Press, 1948.

Gingerich, Melvin. Service for Peace: A History of Mennonite Civilian Public Service. Akron, Pa.: Mennonite Central Committee, 1949. An annotated bibliography appears on pp. 425-428.

National Service Board for Religious Objectors. Directory of Civilian Public Service: May, 1941 to March, 1947. Washington, D.C.: National Service Board for Religious Objectors, 1947.

Sibley, M. Q. and P. E. Jacob. Conscription and Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-1947. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952. Reprinted New York: Johnson Reprint Corp. ; London : Johnson Reprint Co. Ltd., 1965.

Yoder, Edward and Donovan Smucker. The Christian and Conscription—An Inquiry Designed as a Preface to Action. Akron, PA: Mennonite Central Committee, 1945.

| Author(s) | Melvin Gingerich |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1953 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Gingerich, Melvin. "Civilian Public Service." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1953. Web. 3 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Civilian_Public_Service&oldid=114071.

APA style

Gingerich, Melvin. (1953). Civilian Public Service. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 3 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Civilian_Public_Service&oldid=114071.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, pp. 604-611. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.