Revivalism

1959 Article

Introduction

Revival (German, Erweckung; French, Réveil), a term commonly used to refer to renewal and intensification of spiritual life in an existing religious congregation, denomination, region, or country, without implying a doctrinal or organizational change or a basic reform. Revivalism has come to mean a technique by which emphasis is placed upon frequent religious renewal through specific methods adopted to produce a mass religious response on a smaller or larger scale, largely through special meetings with considerable appeal to religious emotions and definite personal commitment.

"Revival" as a descriptive term is not applied to movements of renewal or religious stir in Roman or Greek Catholicism, although certainly such renewals have taken place at various times and places in Christian history. Even for Protestantism the term is usually limited to revival movements since the 18th century, beginning in Germany with Pietism (1670-1750) including Count Nicholas von Zinzendorf and the Moravians (1722 ff.), in England with the Wesleyan Movement (1738 ff.), and in the American Colonies with the Great Awakening of Jonathan Edwards and others (1734-44). This article will focus on the revival movement in North America as it influenced Mennonites or developed among Mennonites themselves.

North America

Nowhere else in the world has revivalism had so wide a spread and so powerful an influence as in the United States, beginning early in the 18th century and continuing into the 20th. As W. W. Sweet explains in his excellent survey Revivalism in America, its origin, growth and decline (New York, 1944), this was due primarily to the specific religious situation in Colonial America produced by the great migrations of generally lower-class European peoples to the New World, the freedom and individualism of American life especially on the frontier, and the extreme weakness of organized religion. As late as 1760 not more than 8-10 per cent of Americans were members of any church, and in the middle colonies of New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland, probably not more than 5-6 per cent. Not only manners but morals were crude, culture was low, educated leaders were scarce, and formal religion had little power. Under these circumstances only a powerful emotionalized, personal religion had much chance to convert America. The conversion was a slow process but it was gradually accomplished, largely as the result of revivalist methods. Those denominations which operated on this level were the greatest beneficiaries of its results, hence the Methodists and Baptists and related groups have become the largest and most influential religious bodies in America.

The first great revival, called the Great Awakening, began in the 1720s with Theodore Frelinghuysen in New Jersey, a pietistic Reformed immigrant preacher, followed by the Presbyterian Tennents in the same area. With the great Jonathan Edwards at Northampton, Mass., it broke out in full power (especially 1734-36) in New England, where 60,000 and more new members were swept into the Congregational and other churches, and the old members greatly revived. George Whitefield, the Calvinistic Methodist from England, made seven journeys to America in 1738-70, becoming the great over-all unifying revival preacher, building up all denominations open to the movement. Thus German Pietism, English Methodism, and New England Calvinism all played a role in this tremendously significant Colonial revival movement. The Moravians in their own way (arrived in Pennsylvania 1738) made their contribution, particularly among the Germans. "Colonial revivalism brought religion to the common man" (Sweet).

It is not clear how much the Colonial Mennonites in Eastern Pennsylvania were involved in or affected by the Great Awakening and its side effects. The claim that they influenced Frelinghuysen or shared in his movement, made by some reputable historians, is unsubstantiated. But that the Mennonites were influenced by Pietism, both before they left the Palatinate (1707 ff.) and in America, especially by pietistic literature, is beyond question. It is highly doubtful, however, that they adopted the revivalist preaching techniques or doctrinal and emotional emphases. They resisted the Moravian influences. The German Tunkers (Dunkards or later Church of the Brethren), who arrived in Eastern Pennsylvania in 1719-22, being themselves Pietists, joined vigorously in the revivalist movement and profited greatly by it, winning many Mennonites to their membership.

Thereafter the Mennonites resisted and rejected the revivalist influences and example until late in the 19th century. The second Great Awakening (1793-1810), the Charles G. Finney revival of 1824-27, the revival of 1853, and others of the first half of the 19th century had little influence upon the Mennonites except to tear large numbers of sheep from the folds of traditional staid Mennonitism. The newer revivalist German denominations such as the United Brethren, founded in 1800 in Eastern Pennsylvania by the former Reformed preacher Otterbein and the former Mennonite bishop Martin Boehm of Lancaster County (who was followed by other Mennonites such as Newcomer), and the Evangelical Church, also founded in 1800 in Eastern Pennsylvania by Jacob Albright, gathered in many dissatisfied Mennonites in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia, and later in Ohio, Ontario, and Indiana. The Church of God (Winebrennerian), founded in Harrisburg, Pa., in 1836, had a similar attraction for Mennonites. Martin Boehm (1725-1812) is the most striking case of the revivalist impact on Pennsylvania Mennonites. Ordained preacher in 1753 and bishop in 1759, he came in contact with Whitefield in Virginia in 1761 and thus was drawn into the Great Awakening. In 1767 he participated in the famous meeting in Isaac Long's barn in the Conestoga Valley in Lancaster County, where he met Otterbein. His ever more extensive revivalist ministry outside the Mennonite Church and his general revivalist practices and beliefs led to his excommunication in 1777. In his later years Boehm greatly influenced the spread of Methodism in the Lancaster area, and his funeral sermon was preached by his friend, Bishop Francis Asbury, the first Methodist bishop in America. The whole course of American Mennonite history in America might have been vastly different if Boehm had succeeded in "revivalizing" it in his day. The Brethren in Christ (River Brethren), who arose in Lancaster County about 1770, were a fruit of the revivalist impact on Mennonites.

Whereas the early revivalism largely took Mennonites out of the church of their fathers (or led to their expulsion), the revivalism of D. L. Moody and others in the 1870s and following more often had the indirect effect of setting revival influences going in the church itself. An outstanding case of this in the Mennonite Church group is John F. Funk (1835-1930), who came directly under Moody's influence in Chicago in the 1860s and was his associate in mission Sunday-school work there. Funk attributed a very strong influence from Moody directly upon himself, which motivated him in turn in his important progressive work in the Mennonite Church. The first Mennonite Church revival meeting was held by Funk and Daniel Brenneman in 1872. John S. Coffman was the great carrier of revivalism into the church 1879-99. By 1900 the church was won over to this method, although it was conservative in its use and did not promote the emotionalist emphasis and the Calvinism or Wesleyanism which often characterized it in general.

Daniel Brenneman in Indiana and Solomon Eby in Ontario did adopt this emotionalist method and emphasis and formed the Mennonite Brethren in Christ Church in 1875, which has been deeply stamped by this point of view.

In the Amish Mennonite Church, Henry Egly (1824-1890) came under the influence of revivalism and founded the small Defenseless (now Evangelical) Mennonite group in Adams County (Berne), Indiana, and elsewhere in 1866. Out of this group later came the Missionary Church Association (1898 at Berne, Indiana, USA).

The General Conference Mennonites, whose major elements were the Oberholtzer group (1847) in Eastern Pennsylvania, Swiss Mennonites in Ohio and Indiana coming in 1818 ff. and 1838 ff., and Russian Mennonites in the western states and provinces since 1874, have undoubtedly also been influenced by Pietism and revivalism, although William Gehman and his Evangelical Mennonites (formed from the Oberholtzer group in 1858) represent a revivalist influence which was excised from the General Conference Mennonite Church. Daniel Hoch (1806-1878) of Ontario (ordained bishop by Oberholtzer in 1851) left the group with his followers in 1869 to join the later Mennonite Brethren in Christ.

The Mennonite Brethren (formed in 1860 in Russia; in the United States since 1874) represent the revivalist movement in a wholesome way and were joined in this by the Krimmer Mennonite Brethren ( formed in Russia in 1869; in the United States since 1874) and the Evangelical Mennonite Brethren (formed from the General Conference Mennonite Church in 1889).

In general the revivalist influence has been wholesome in those groups which have remained Mennonite in basic and historic character. The groups which have left the Mennonite brotherhood have adopted a more emotionalized type of piety, together with general Wesleyan emphasis on "holiness" and the second work of grace or also entire sanctification or perfectionism. The "Camp Meeting" was adopted by the Mennonite Brethren in Christ from the earlier Methodist revivalism.

In the Mennonite Church (MC), as well as in the Mennonite Brethren Church and related groups, the general adoption of the revivalist pattern for securing new members led to the use of this method for bringing the children of the church into church membership in place of the older method of catechetical instruction and baptism at a traditional age of 14-18 years. The revivalist emphasis upon personal conversion and decision is in principle, so long as it is not pressed upon children at too early an age or induced by emotionalized pressures, in accord with the Anabaptist understanding of faith as personal, voluntary acceptance of Christ as Savior and Lord. Apart from undesirable excesses revivalism may therefore be understood as a renewal in a sense of the central Anabaptist emphases. -- Harold S. Bender

Europe

The term Réveil is applied to a revival movement in the renewal of Pietism in the train of the Romantic movement in the early 19th century in western Europe, especially Holland. It is treated in the following series of articles.

West Switzerland and France

As early as 1805 several inspired members of a small congregation of Bohemian Brethren in Geneva, viz., Ami Bost (1790-1874), Henri Louis Empaytaz (1790-1853), and others, met with some late adherents of Pietism. Soon external influences were added. In 1813 Mrs. von Krüdener (1764-1824), converted in 1807, appeared, in connection with Jung-Stilling, in 1816 Robert Haldane (1764-1846), who was giving an exegesis of the epistle to the Romans in Geneva and with whom other Scots were working. The Anabaptist concept of "a church after the pattern of the apostolic church, which recognizes only converted persons and rejects infant baptism, was accepted by many awakened Christians" (Hadorn, 431). In 1841, after theological professors and pastors had rejected a reformation, and a transfer to the Catholic Church had been briefly considered, the first free church arose, known as the New Church (nouvelle église). Others then began to preach in the established church the forgotten doctrines of Calvin, such as original sin, predestination, etc. When Cesar Malan (1787-1864) was refused a pulpit he opened in his garden the Chapel of the Testimony (chapelle du temoignage), which in 1823 became the second free church. This was the origin of the Free Evangelical Churches. Louis Gaussen (1790-1863) was one of the founders of the Evangelical Association, for the defense of the evangelical faith within the established church. He was soon deposed from his pulpit; he then accepted a teaching position in the theological faculty of the Evangelical Association, which was founded in 1832, and in his Theopneustia (1840 and 1842) he taught the doctrine of the verbal inspiration of the Old and New Testaments.

The movement spread into France (Free Church in 1832, Evangelical Association in 1833, the Monod brothers as leaders), and also to the cantons of Vaud and Lausanne in Switzerland, where Alexander Vinet (1797-1847) was the leading personality and where a Free Church and a free theological faculty came into existence, and into Neuchâtel, where a revival had begun in 1817, though the Free Church and the free faculty were not instituted until Frederic Godet initiated them.

In Bern a Free Church was begun in 1829 and an Evangelical Association in 1831.

The Evangelical Association of the canton of Bern, as well as the Free Protestant churches, have had many contacts with the Mennonites in the canton of Bern. The Mennonite Der Zionspilger was called Der freie Zeuge in 1918-1921. Since 1868 and particularly since 1912 the Swiss Mennonites have been connected with revival movements.

North Switzerland and Adjacent South Baden

The revival movement here was an outgrowth of the German Association for Christianity (Deutsche Christentumsgesellschaft) with its seat in Basel, Switzerland, which was founded by Johann August Urlsperger (1728-1806) in 1780 for the promotion of pure doctrine and true godliness (Gottseligkeit). Friedrich Steinkopf (1773-1859), who was the secretary of this association 1795-1800, brought in English inspiration. William Carey (1761-1834) had founded the Baptist Missionary Association in 1792; the Religious Tract Society was founded in 1799; and the British and Foreign Bible Society in 1804. Gottlieb Blumhart (1779-1838), the revivalistic pastor of St. Peter's Church in Basel and long-time secretary of the Association for Christianity, was under the same influence. At times in 1816 f., Mrs. von Krüdener with her stormy enthusiasm stayed in and around Basel. Christian Friedrich Spittler (1782-1867), like Steinkopf and Blumhardt a native of Württemberg, but a layman, also a secretary of the Association for Christianity in 1801 f., "a personality who believed and achieved the incredible" (Hadorn, 493), formed the focal point with his organization. In 1804 the Basel Bible Society came into being. In 1815 in the castle Beuggen am Rhein, which the Grand Duke of Baden put at their disposal under the leadership of Christian Heinrich Zeller (1779-1860), a seminary was organized for the training of teachers for the schools of the poor and a rescue home for neglected children of the poor. In 1840 Spittler's favorite work, St. Chrischona, near Basel, was founded as an institution for the training of workers for home mission work, in 1865-1883 and 1890-1909 under the leadership of Heinrich and Dora Rappard (1837-1909 and 1842-1923). The school at Beuggen educated many a Mennonite, among them Jakob Ellenberger (1800-1879) and Michael Löwenberg (1821-1874), the founder of the school at Weierhof. "Between Zeller and the Mennonites there was a fraternal relationship and mutual confidence. He never entered into theological arguments with them, but he told the Mennonites, 'If you cannot decide to have your children baptized, you should at least bring them to Jesus in a ceremonial service, and ask Him to bless them' (Thiersch, 676)." The Pilgermission school at St. Chrischona educated the Mennonite elders Fritz Goldschmitt, Samuel Nussbaumer, Samuel Gerber, Hans Rüfenacht, and Theo Loosli of Switzerland, and Pierre Sommer of Montbeliard, France, and in Germany the ministers Johannes Hirschler of Monsheim, Matthias Pohl (1860-1934) of Sembach, Michael Landes, Jakob Hege, Gysbert van der Smissen (1859-1923), Emanuel Landes, the son of the above Michael Landes, and Christian Schnebele, the superintendent of Thomashof. -- Ernst Crous

Germany

In Württemberg leading spirits in the movement at this time were Ludwig Hofacker (1798-1828, converted 1816), whose sermons were much read by German Mennonites (even in South Russia, where they contributed to the rise of the Mennonite Brethren), the poet Albert Knapp (1798-1864), and J. C. Blumhardt (1805-1880). Noteworthy is the establishment of the millennialistic community of Korntal near Stuttgart (1819), also the emigration of separatistic groups of revivalistic type to South Russia about 1843, among whom was Eduard Wüst (1817-59), who was a major influence in the rise of the Mennonite Brethren.

In Berlin the movement found leaders in several professors at the universities of Berlin (August Neander, 1789-1850, E. W. Hengstenberg, 1802-1869) and Halle (August Tholuck, 1799-1877). In Hamburg the Mennonite deacon J. G. van der Smissen (1746-1829), influenced by the bookseller Friedrich Perthes, became much involved, serving as secretary of the Hamburg Bible Society (founded 1814). He was also connected with Johann Gossner (1773-1858). In the Lower Rhine-Westphalia region Barmen became a center, where a mission school was started in 1828, which was later attended by a number of Mennonites (Heinrich Dirks, 1842-1915, the first Russian Mennonite missionary. Thomas Löwenberg, 1849-1928, preacher at Weierhof and Ibersheim, and Ernst Regehr, elder at Rosenort in West Prussia and later at El Ombu, Uruguay). Early leaders of the movement in this general area were the Krummachers (Friedrich Adolf, 1767-1845, and Friedrich Wilhelm, 1796-1868). Isaak Molenaar (1776-1834), preacher at Leiden, Holland, 1813-1818 and from 1818 on at Crefeld, was influenced by the movement.

The imported Anglo-Saxon Methodist (1831), Baptist (1834), Plymouth Brethren (1848), and Evangelical Association (1850) groups prospered in Germany largely as a result of the revival movement, as did also the Free Evangelical Church, which entered Germany from Geneva via Lyons in 1854. The Baptist Seminary in Hamburg-Horn was attended by a number of Mennonites from Russia (Jacob Kroeker studied here 1894-98, J. G. Wiens 1899-1903, and Abraham Warkentin 1912-15). -- Ernst Crous

Netherlands

About 1820, influenced by revivalist movements in Geneva and the canton of Vaud in Switzerland, and by Scottish and English revivalism, a religious revival arose in the Netherlands, which is usually known as the "Réveil."

The Réveil was opened by the Dutch poet and historian Willem Bilderdijk (1756-1831), who continuously and fervently attacked the halfheartedness and lack of Biblical fundamentalism of the Reformed Church of Holland. Bilderdijk became the spiritual leader of a number of close followers, among whom were the converted Jews, Isaac da Costa (1798-1860), who in 1823 published Bezwaren tegen den geest der eeuw (Complaints Against the Spirit of this Age), attacking political and religious liberalism quite in the style of Bilderdijk, and Abraham Capadose (1795-1874), both of Amsterdam. The Réveil, which at first had its center at Amsterdam, also had a group of followers at The Hague from about 1832. Its aim was to fight rationalism and liberalism, with a plea "back to the Bible"; hence their leaders conducted numerous Bible courses (particularly da Costa) and founded Sunday schools for children. Great stress was laid upon the experience of knowing Jesus Christ as the Saviour and Redeemer. In the large cities missions were started, rousing the people to personal conversion. The Réveil had a typically pietistic background, which, though distrusted by da Costa and others, was never denounced, and predominated in the activities of Jan de Liefde and others.

The Réveil movement gathered its followers particularly from the upper classes. From about 1830 it took a keen interest in charity, at this time greatly neglected by the churches, and much was done for the relief of social needs. The "Christian Friends," as they often called themselves, made contact with kindred spirits abroad and often followed their examples. Thus in 1844 a deaconess hospital was opened in Holland on the pattern of the Theodor Fliedner's deaconess house at Kaiserswerth, Germany. The Réveil also prepared the way for the founding of special Christian schools.

In 1834 a number of members left the Dutch Reformed Church, to restore the church on the basis of Calvinism as formulated in the resolutions of the national Dutch Reformed synod held at Dordrecht in 1619. This caused a difference of opinion in the Réveil group, some of whom joined the separatists, who founded a new Reformed church, while others held to the (old) Reformed church, as did da Costa, who said that their position should not be juridical but medical ("Together we have become sick, together we should recover"), hence no separation. After 1850 the Réveil lost much of its strength and influence, but its adherents continued their activities and meetings until after 1865.

Although the Réveil as a movement was favored particularly by the Reformed, a number of Mennonites were actively engaged in it. The most prominent of these was Willem de Clercq (1795-1844) of Amsterdam, who was for many years a close friend of da Costa. Others were Willem Messchaert (1790-1844) of Rotterdam, Jan ter Borg (1782-1847), a Mennonite minister at Amsterdam, and in later times Jan de Liefde (1814-1869) and Pieter van der Goot (1817-1877), who was also a Mennonite minister at Amsterdam.

The Mennonites who became interested in the Réveil were all more or less dissatisfied with the spiritual atmosphere of the Dutch Mennonite brotherhood. As was also the case in the Reformed Church, spiritual life in the church was at this time at a low level, the sermons being rationalistic or moralistic lectures rather than evangelical messages. Most of the Mennonite friends of the Réveil left the Mennonite Church—Messchaert in 1829; de Clercq, who from 1825 took a great interest in the development of the Reformed Church and had his children baptized, officially terminated his membership in the Mennonite Church in 1831; ter Borg resigned his office in 1829, but did not leave the church; de Liefde left the Mennonite pulpit and his congregation in 1845; van der Goot tried to realize some of the Réveil principles in the Mennonite congregation of Amsterdam. -- Nanne van der Zijpp

1990 Update

The word "revival" is commonly used in both the sense of renewal, or awakening, and to describe a technique developed during the Second Great Awakening (ca. 1795-1810) and its aftermath. This article is concerned primarily with the latter, but will give cross references to renewal movements as well. Revival meetings were a pervasive technique for evangelism and spiritual renewal in American Protestant churches for a century and a quarter, from ca. 1830 to 1955, although they both preceded and followed these dates. Revival meetings commonly consisted of consecutive nightly meetings, together with weekend services, which extended over a week or more. Emotional messages stressing sin and salvation called for repentance expressed by an individual response to a personal invitation to accept salvation. Gospel songs reinforced this message (hymnology). Beginning late in the 19th century, Mennonites widely adopted this form of revivalism.

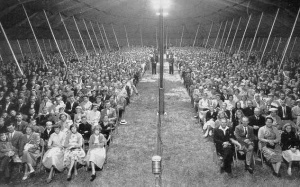

In the 1950s mass revivals held in tents, stadiums, or large auditoriums became common throughout America. Mass tent revivals were begun in the Mennonite churches when George B. Brunk II, a graduate of Union Theological Seminary (Richmond, Virginia) and ordained preacher, joined forces with his brother Lawrence, who served as business manager and song leader for their campaigns until 1953. Their first series of meetings began in June 1951 at East Chestnut Street in Lancaster, PA, and continued for seven weeks. It was followed that summer and fall by campaigns at Souderton, Pennsylvania; Orrville, Ohio; Manheim, Pennsylvania; and, during the winter, in Sarasota, Florida. The meetings quickly became inter-Mennonite. A spring 1952 campaign in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, was followed by a July campaign in Kitchener, Ontario, cooperatively sponsored by the Ontario Mennonite Conference (MC) and local churches, including the Amish Mennonites, Mennonite Brethren, the Stirling Avenue and United Mennonite congregations (GCM), the United Missionary Church, and the Brethren in Christ.

A second Mennonite tent revival unit was sponsored in 1952 by Christian Laymen's Tent Evangelism, Inc. (CLTE), with headquarters in Orrville, Ohio. Howard Hammer, formerly a United Brethren in Christ minister, was the first evangelist, followed in 1955 by Myron Augsburger, when Hammer went to South America as a missionary. Andrew Jantzi, an evangelist from the Conservative Amish Mennonite Church, led a third organization which was largely confined to his own denomination. A fourth organization, Mennonite Evangelical Crusades (sponsored by the Virginia Mennonite Conference [MC]) held four campaigns in 1956 and one in 1957 with A. Don Augsburger as speaker.

In 1955 the Brunk Revivals, with Lawrence no longer a part of the team, went to Rosthern, Saskatchewan. The series was initially sponsored by the General Conference Mennonite Church, but soon other groups were cooperating. In the summer of 1956 Brunk Revivals returned to Saskatchewan to hold meetings at Osler and Swift Current, followed by additional series in Dolton, South Dakota, and Mountain Lake, Minnesota. In the summer of 1957 tent meetings were held in southern Manitoba and sponsorship included the Mennonite Brethren, Evangelical Mennonite Brethren, Evangelical Mennonite Conference (Kleine Gemeinde), General Conference Mennonites, Bergthal Mennonites, Rudnerweide Mennonites (Evangelical Mennonite Mission Conference), Blumenorter Mennonite, and two non-Mennonite groups, the Evangelical Free Church and the Emmanuel Church. In the summer of 1958 the Brunk Revivals went to British Columbia, with the meetings under the sponsorship of the General Conference Mennonite Church, Mennonite Brethren, and Evangelical Mennonite Brethren. In the late 1950s, under the leadership of Myron Augsburger, CLTE began holding meetings in large urban auditoriums as well as tents. Renamed Crusade for Christ, the operation elicited interdenominational sponsorship. The summer of 1958 began with a city-wide campaign in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, followed by another in Fort Wayne, Indiana in August. A March 1959 series in Convention Hall, Hutchinson, Kansas was sponsored by 70 churches in the city together with the Christian Business Men's Association, Youth for Christ, and the Gideons organization. In January 1959, the parent organization modified its name to Christian Laymen's Evangelical Association, since it was no longer holding meetings in tents, and the public name of the meetings became Augsburger Crusades. In 1962 the organization disbanded, the tent was sold, and the monies distributed to Mennonite missions. The last Brunk campaign was held in Landisville, Pennsylvania in July 1982, after which the tent and equipment were sold, and a foundation was formed to allocate the proceeds to continuing evangelistic work.

The mass revivals elicited widespread response in church periodicals from 1951 to 1953. Initial affirmative reports of the meetings were followed by articles endeavoring to associate the revivals with a renewed emphasis on evangelism in the Mennonite churches. By the end of 1953 it became apparent that although the meetings were stimulating renewal, they were not primarily evangelistic, i.e., reaching unchurched, non-Mennonite individuals.

The General Council of Mennonite Church [MC] General Conference adopted "A statement of concerns on revivalism and evangelism" in April 1953. The statement was basically supportive of the mass revivals, but concerns were also in evidence, including the primary-junior age of baptism that was becoming common. The concern over child evangelism prompted a formal study beginning in 1953, and a subsequent statement, entitled "Position on the nurture and evangelism of children." It was adopted by Mennonite Church [MCI General Conference in 1955. Additional revivalist emphases that made Mennonites uncomfortable were: (1) the prominence given to the confrontation of the individual with the devil and to the theme of the wrath of God; (2) the focus on the individual; and (3) conversions that did not result in church membership. Mennonites traditionally believed that God's love, not his wrath, shaped his relationship with mankind. Furthermore, although the cooperation of local community churches was solicited for the mass campaigns, the setting essentially removed the experience from the congregational context. Whereas traditionally conversion and church membership were closely associated, in revivalism the individual's relationship to the church was considered secondary. Revivalism, its critics charged, aimed at crisis commitment to faith in Christ, while giving little attention to full discipleship.

Mennonites had always considered the new birth essential, but repentance and the will were held to be more important than experience or feeling. From its beginning phases in the First Great Awakening (1730s-1770s), revivalism caused divisions among Mennonites, drawing off its most enthusiastic supporters into new denominations. As the Pennsylvania German Revival climaxed in the late 18th century, it was responded to by Christian Burkholder in Nützliche und Erbauliche Anrede an die Jugend (Useful and edifying address to the young), 1804. A few decades later, during the Second Great Awakening, Abraham Godschalk wrote on Becoming a new creature (1838). In the late 19th century, during the Third Great Awakening, the influential leader John M. Brenneman published Hope, sanctification, and a noble determination. Both Brenneman and Godschalk presented the Mennonite understanding of obedience and commitment in opposition to revivalist teachings.

The Mennonite Brethren Church grew out of a pietistic revival in Russia, and itinerant evangelism has characterized this group in both Russia and America. Multiple lay evangelists served the church extensively from 1910 to 1954. With a decline in their availability at mid-century, evangelists from interdenominational organizations began to be used. Concern over this trend prompted the appointment of conference evangelists from 1954 to 1972. Among the persons serving in this program were Loyal A. Funk as chairman of the Board of Evangelism with Waldo Wiebe, David J. Wiens, Henry J. Schmidt (and in Canada H. H. Epp) serving as conference evangelists. Elmo Warkentine, as executive secretary of the board, implemented a church wide program of training for evangelism.

For the first six decades of the 20th century revivalism and resultant "quickening" in Mennonite churches was viewed positively by historians. Since the mid-1970s new scholarship has observed both that Mennonites had more interaction with the First and Second Great Awakenings than was formerly supposed and that revivalism altered Mennonite understandings of the Gospel (Schlabach, Sutter, and Hostetler).

William G. McLoughlin in his book, Revivals, Awakenings, and Reform, has closely associated widespread religious awakenings with profound cultural transformation. As areas of the Mennonite church embraced revivalism in the 19th and early 20th century, major adjustments were being made to American cultural patterns. Similarly, in the 1950s and 1960s the Mennonite Church [MC] was experiencing profound transformation in religious forms , structured programs, and cultural interaction. The mass revivals brought spiritual revival for many and the unleashing of energies which found expression in new programs.

Revivalism in the Mennonite churches waned by the late 1950s, although some tent meetings continued to be held. Many congregations discontinued revival meetings. Some of the functions of revival meetings were taken over by the burgeoning camping movement where fireside services often functioned as revival meetings, frequently with a very young age group. By 1970 the charismatic movement was also providing a base for renewal. -- Beulah S. Hostetler

Bibliography

Beardsley, F. G. A History of American Revivals. New York, 1904.

Bender, H. S. Mennonite Sunday School Centennial. Scottdale, PA, 1940.

Brunk, Harry A. History of Mennonites in Virginia, 1900-1960. Verona: McClure Printing Co., Inc. 1972: 447-449.

Brunk, George II. "Which Gospel is it." Gospel Herald (26 May 1981): 409-411.

Cronk, Sandra Lee. "Gelassenheit: the Rites of the Redemptive Process in Old Order Amish and Old Order Mennonite Communities." PhD diss., U. of Chicago, 1977: esp. 270-80, cf. Mennonite Quarterly Review 55 (1981): 5-44.

Crous, Ernst. "Mennonitentum und Pietismus." Theologische Zeitschrift VIII (1952): 279-96.

Crous, Ernst. "Vom Pietismus bei den altpreussischen Mennoniten . . . 1772-1945." Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter (1954): 7-29.

Dickey, Dale Franklin. "The Tent Evangelism Movement in the Mennonite Church: a Dramatic Analysis." PhD diss., Bowling Green State U. 1980, although shaped toward the discipline of speech and communications, this is the most complete account of the Mennonite mass tent revival movement.

Epp, Frank H. Mennonites in Canada, 1920-1940: a People's Struggle for Survival. Toronto: Macmillan, 1982: ch. 6.

Epp, Frank H., ed. Revival Fires in Manitoba. Denbigh, VA: Brunk Revivals, Inc., 1957.

Goeters, W. Die Vorbereitung des Pietismus in der Reformierten Kirche . . . Leipzig, 1911.

Hadorn, W. Geschichte des Pietismus in den Schweizerischen Reformierten Kirchen. Constance, 1901.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. III, 482-84.

Hostetler, Beulah S. American Mennonites and Protestant Movements. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1987: 150-75, 279-87.

Kauffman, Nelson E. "Report of the First Annual Meeting of Christian Laymen's Evangelism, Inc." Gospel Herald (5 February 1953): 102-103.

Klassen, A. J ., ed. Revival Fires in British Columbia. Denbigh, VA: Brunk Revivals, Inc., 1958.

Kluit, M. E. Het Réveil in Nederland. Amsterdam, 1936.

Kratz, Clyde G. "Mixed Blessings." Unpublished term paper, Eastern Mennonite College, 1985, an analysis of the Brunk campaign in Souderton, PA in 1951 (copy at Menno Simons Historical Library, Harrisonburg, Virginia, USA).

Latourette, K. S. A History of the Expansion of Christianity III, IV. New York, 1939, 1941.

Lederach, Paul M. "Revival in Franconia." Gospel Herald (18 September 1951): 902-903.

Lehman, Maurice E. "The Lancaster Revival." Gospel Herald (4 September 1951): 852-853.

McLoughlin, William G. Revivals, Awakenings, and Reforms. Chicago: U. of Chicago Press, 1978.

Miller, Joseph S. "The Pennsylvania Mennonite Church Near Zimmerdale, Kansas." Pennsylvania Mennonite Heritage 5, no. 3 (July 1982): 14-19.

Miller, Joseph S. "The Kansas Movement: Paul Erb's Viewpoint." Pennsylvania Mennonite Heritage 5, no. 3 (July 1982): 20-22.

Penner, Peter. "Reflections on Mass Evangelism." Christian Leader (July 1961): 4, 5, and 19.

"Position on the Nurture and Evangelism of Children." Mennonite General Conference [MC] Proceedings (1955): 53-55.

Schlabach, Theron F. "Reveille for die Stillen im Lande: a Stir Among Mennonites in the Late Nineteenth Century." Mennonite Quarterly Review 51 (1977): 213-26.

Schlabach, Theron F. "Mennonites, Revivalism, Modernity, 1683-1850." Church History (1979): 298-415.

Schlabach, Theron F. Gospel Versus Gospel. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1980.

Shank, Katie F. Revival Fires. Broadway VA: the author, 1952.

Smith, C. Henry. The Story of the Mennonites. Newton, KS, 1957.

Stambaugh, Sarah. I Hear the Reaper's Song. Intercourse, PA: Good Books, 1984.

"A Statement of Concerns on Revival and Evangelism, adopted by the General Council of General Conference." Gospel Herald (18 August 1953): 777.

Sutter, Sem C. "Mennonites and the Pennsylvania German Revival." Mennonite Quarterly Review 50 (1976): 37-57.

Sweet, W. W. Revivalism in America, Its Origin, Growth and Decline. New York, 1944.

Sweet, W. W. The Story of Religion in America. New York, 1950.

Tiesmeyer, Ludwig. Die Erweckungsbewegung in Deutschland wahrend des XIX. Jahrhunderts I-IV. Kassel, 1901-12.

Toews, John A. History of the Mennonite Brethren Church, ed. A. J. Klassen. Fresno, CA : Mennonite Brethren Board of Literature and Education, 1975.

Wenger, Mark B. "Ripe Harvest: A. D. Wenger and the Birth of the Revival Movement in Lancaster Conference." Pennsylvania Mennonite Heritage 4, no. 2 (April 1981): 2-14.

Wittlinger, Carlton O. "The Advance in Wesleyan Holiness Among the Brethren in Christ since 1910." Mennonite Quarterly Review 50 (1976): 21-36.

Wittlinger, Carlton O. "The Impact of Wesleyan Holiness on the Brethren in Christ to 1910." Mennonite Quarterly Review 49 (1975): 259-283.

| Author(s) | Harold S. Bender |

|---|---|

| Ernst Crous | |

| Nanne van der Zijpp | |

| Beulah Stauffer Hostetler | |

| Date Published | 1990 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Bender, Harold S., Ernst Crous, Nanne van der Zijpp and Beulah Stauffer Hostetler. "Revivalism." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1990. Web. 2 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Revivalism&oldid=103547.

APA style

Bender, Harold S., Ernst Crous, Nanne van der Zijpp and Beulah Stauffer Hostetler. (1990). Revivalism. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 2 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Revivalism&oldid=103547.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 4, pp. 308-312; vol. 5, pp. 771-773. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.