Difference between revisions of "Ukraine"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m (Added category.) |

SusanHuebert (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

[[File:Ukraine.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Source: [http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Main_Page Wikipedia Commons]'']] | [[File:Ukraine.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Source: [http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Main_Page Wikipedia Commons]'']] | ||

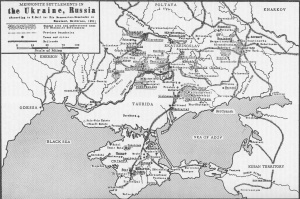

[[File:ME4_764.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Source: Mennonite Encyclopedia v. 4, p. 764'']] | [[File:ME4_764.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Source: Mennonite Encyclopedia v. 4, p. 764'']] | ||

| − | <h3>Introduction</h3> Ukraine (Russian, <em>Ukraina</em>), formerly the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, a republic of the USSR located in the southwest, on the north shore of the Black Sea ([[Crimea (Ukraine)|Crimea]] not included), consisted of 171,770 square miles with a population of 30,960,221 (1939) which was increased during [[World War (1939-1945) - Soviet Union|World War II]] to 213,473 square miles and a population of 40,600,000 (1950), (in 2005 the country, independent since 1991, consisted of 233,090 square miles with an estimated population of 46,481,000). The name Ukraine is popularly believed to mean "borderland," but Ukrainian nationalists interpret it to mean "cut off from something in one’s possession" (<em>Slavonic Encyclopedia</em>: 1, 325). The story of Ukraine consists of chapters of nationalism, oppression, heroism, and victory. Kiev, the capital of Ukraine played a significant role in the early history of [[Russia|Russia]]. The Cossacks became the protectors and defenders of Ukraine against the Mongolian occupants and invaders. | + | <h3>Introduction</h3> Ukraine (Russian, <em>Ukraina</em>), formerly the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, a republic of the USSR located in the southwest, on the north shore of the Black Sea ([[Crimea (Ukraine)|Crimea]] not included), consisted of 171,770 square miles with a population of 30,960,221 (1939) which was increased during [[World War (1939-1945) - Soviet Union|World War II]] to 213,473 square miles and a population of 40,600,000 (1950), (in 2005 the country, independent since 1991, consisted of 233,090 square miles with an estimated population of 46,481,000). The name Ukraine is popularly believed to mean "borderland," but Ukrainian nationalists interpret it to mean "cut off from something in one’s possession" (<em>Slavonic Encyclopedia</em>: 1, 325). The story of Ukraine consists of chapters of nationalism, oppression, heroism, and victory. Kiev, the capital of Ukraine, played a significant role in the early history of [[Russia|Russia]]. The Cossacks became the protectors and defenders of Ukraine against the [[Mongolia|Mongolian]] occupants and invaders. |

In Mennonite history the final subjugation of Ukraine by [[Catherine II, Empress of Russia (1729-1796)|Catherine II]] (Empress of Russia, 1762-96) played a significant role. She had [[Potemkin, Prince Grigori Alexandrovich (1739-1791)|Grigori Alexandrovich Potemkin]] colonize and settle Ukraine by a transfer of population from central Russia and the invitation of foreign settlers to Russia. This has been presented in greater detail in the article [[Russia|Russia]]. | In Mennonite history the final subjugation of Ukraine by [[Catherine II, Empress of Russia (1729-1796)|Catherine II]] (Empress of Russia, 1762-96) played a significant role. She had [[Potemkin, Prince Grigori Alexandrovich (1739-1791)|Grigori Alexandrovich Potemkin]] colonize and settle Ukraine by a transfer of population from central Russia and the invitation of foreign settlers to Russia. This has been presented in greater detail in the article [[Russia|Russia]]. | ||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

Before [[World War (1914-1918)|World War I]] Ukraine had become the chief producer of grains, particularly wheat. The Mennonites contributed to making Ukraine the breadbasket of Europe by introducing new methods of [[Agriculture among the Mennonites of Russia|agriculture]] and by developing flour industries in various areas. In 1955 however, Ukraine produced only 14 percent of the total Soviet output of grain, having become more important in industrial pursuits. The iron located near Krivoi Rog, and manganese at Nikopol, which utilize the coal of the Don Region, are significant for industry. Hydroelectric power is produced at the great Dneprostroi Dam in the region of the former Mennonite settlement of [[Chortitza Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Chortitza]]. Some of the major industrial centers and cities are Kiev, Kharkov, Odessa, Dnepropetrovsk (formerly [[Ekaterinoslav (Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, Ukraine)|Ekaterinoslav]]), [[Zaporizhia (Ukraine)|Zaporizhia]] (formerly Alexandrovsk), and [[Chortitza (Chortitza Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Chortitza]]. The foundation for some of these industrial centers, e.g., the last two, was laid by Mennonites. The reason for the shift from agriculture to industry is the fact that the Soviet Union had opened up vast territories for agriculture east of the Ural Mountains and is industrializing the country rapidly, which results in a greater emphasis on the latter in Ukraine. | Before [[World War (1914-1918)|World War I]] Ukraine had become the chief producer of grains, particularly wheat. The Mennonites contributed to making Ukraine the breadbasket of Europe by introducing new methods of [[Agriculture among the Mennonites of Russia|agriculture]] and by developing flour industries in various areas. In 1955 however, Ukraine produced only 14 percent of the total Soviet output of grain, having become more important in industrial pursuits. The iron located near Krivoi Rog, and manganese at Nikopol, which utilize the coal of the Don Region, are significant for industry. Hydroelectric power is produced at the great Dneprostroi Dam in the region of the former Mennonite settlement of [[Chortitza Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Chortitza]]. Some of the major industrial centers and cities are Kiev, Kharkov, Odessa, Dnepropetrovsk (formerly [[Ekaterinoslav (Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, Ukraine)|Ekaterinoslav]]), [[Zaporizhia (Ukraine)|Zaporizhia]] (formerly Alexandrovsk), and [[Chortitza (Chortitza Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Chortitza]]. The foundation for some of these industrial centers, e.g., the last two, was laid by Mennonites. The reason for the shift from agriculture to industry is the fact that the Soviet Union had opened up vast territories for agriculture east of the Ural Mountains and is industrializing the country rapidly, which results in a greater emphasis on the latter in Ukraine. | ||

| − | <h3>Mennonite Settlements</h3> Ukraine was a major attraction in 1789-1840 not only for the Mennonites, but also for other foreign settlers, particularly from Germany. Two of the major German settlements were those located in the region of Odessa, and in the Molotschna with a center named Prischib. The Mennonites were in touch with these settlements and this interchange of cultural ideas and stimulation was of mutual benefit. | + | <h3>Mennonite Settlements</h3> Ukraine was a major attraction in 1789-1840 not only for the Mennonites, but also for other foreign settlers, particularly from Germany. Two of the major German settlements were those located in the region of Odessa, and in the Molotschna with a center named [[Prischib (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Prischib]]. The Mennonites were in touch with these settlements and this interchange of cultural ideas and stimulation was of mutual benefit. |

The most significant provinces of Ukraine for the Mennonites were [[Ekaterinoslav Guberniya (Ukraine)|Ekaterinoslav]], [[Taurida Guberniya (Ukraine)|Taurida]], [[Kherson (Kherson Oblast, Ukraine)|Kherson]], and [[Kharkov (Ukraine)|Kharkov]]. In [[Ekaterinoslav Guberniya (Ukraine)|Ekaterinoslav]] the two mother settlements of [[Chortitza Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Chortitza]] and [[Molotschna Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Molotschna]] were located. Of the 50 or more Mennonite daughter settlements established in Russia 20 were located in [[Ekaterinoslav Guberniya (Ukraine)|Ekaterinoslav]], six in Taurida, four in Kherson, and two in Kharkov, making a total of 32 in Ukraine, not counting the many large private estates. Of the approximately 120,000 Mennonites located in Russia before [[World War (1914-1918)|World War I]], about 75,000 lived in Ukraine (Ehrt, 153); and of the approximately 3,000,000 acres (see ME I, 25) of land owned by the Mennonites of Russia at that time, approximately half (Ehrt, 83) was located in Ukraine. This does not include the Mennonite population and land located in the [[Crimea (Ukraine)|Crimea]], the [[Caucasus|Caucasus]], the Don Region along the Volga River, or in central Russia. The major Mennonite industrial and business centers were located in Ukraine. This was also true of educational institutions and religious and cultural centers. | The most significant provinces of Ukraine for the Mennonites were [[Ekaterinoslav Guberniya (Ukraine)|Ekaterinoslav]], [[Taurida Guberniya (Ukraine)|Taurida]], [[Kherson (Kherson Oblast, Ukraine)|Kherson]], and [[Kharkov (Ukraine)|Kharkov]]. In [[Ekaterinoslav Guberniya (Ukraine)|Ekaterinoslav]] the two mother settlements of [[Chortitza Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Chortitza]] and [[Molotschna Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Molotschna]] were located. Of the 50 or more Mennonite daughter settlements established in Russia 20 were located in [[Ekaterinoslav Guberniya (Ukraine)|Ekaterinoslav]], six in Taurida, four in Kherson, and two in Kharkov, making a total of 32 in Ukraine, not counting the many large private estates. Of the approximately 120,000 Mennonites located in Russia before [[World War (1914-1918)|World War I]], about 75,000 lived in Ukraine (Ehrt, 153); and of the approximately 3,000,000 acres (see ME I, 25) of land owned by the Mennonites of Russia at that time, approximately half (Ehrt, 83) was located in Ukraine. This does not include the Mennonite population and land located in the [[Crimea (Ukraine)|Crimea]], the [[Caucasus|Caucasus]], the Don Region along the Volga River, or in central Russia. The major Mennonite industrial and business centers were located in Ukraine. This was also true of educational institutions and religious and cultural centers. | ||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

In this program of expansion the mother settlements of Ukraine, particularly their respective centers, such as Chortitza, Halbstadt, Orloff, and Gnadenfeld, maintained their importance as economic, cultural, and religious centers. The churches established in many of the new settlements remained subsidiaries of the mother churches in Ukraine for a generation. In spite of the distance, cultural and religious ties kept the daughter settlements attached to their mother settlements. In many instances the mother settlement financed and supervised the settlement of its [[Landless (Landlose)|landless]] population. As a rule in the layout of the villages, the construction of the homes, and the organization of cultural and religious life in the new settlements, they closely resembled the mother settlement, although an adjustment to geographic, climatic, and other local conditions was noticeable. | In this program of expansion the mother settlements of Ukraine, particularly their respective centers, such as Chortitza, Halbstadt, Orloff, and Gnadenfeld, maintained their importance as economic, cultural, and religious centers. The churches established in many of the new settlements remained subsidiaries of the mother churches in Ukraine for a generation. In spite of the distance, cultural and religious ties kept the daughter settlements attached to their mother settlements. In many instances the mother settlement financed and supervised the settlement of its [[Landless (Landlose)|landless]] population. As a rule in the layout of the villages, the construction of the homes, and the organization of cultural and religious life in the new settlements, they closely resembled the mother settlement, although an adjustment to geographic, climatic, and other local conditions was noticeable. | ||

| − | The | + | The increase in large estate owners, who were particularly numerous in Ukraine, is a chapter in itself. [[Cornies, Johann (1789-1848)|Johann Cornies]] in the early days, and the Sudermann, Dyck and Schmidt families in the later days, owned large estates. A total of 384 large estates comprised three tenths of the land owned by Mennonites in Russia. The largest estate in Ukraine was a ranch of 50,000 acres. (ME I, 25). |

The following is a table of the two mother settlements of Ukraine, Chortitza and Molotschna, and the daughter settlements of these two that were established in Ukraine. (For a complete list of all settlements, see the article [[Russia|Russia]].) | The following is a table of the two mother settlements of Ukraine, Chortitza and Molotschna, and the daughter settlements of these two that were established in Ukraine. (For a complete list of all settlements, see the article [[Russia|Russia]].) | ||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

<h3>Religious Life and Migrations</h3> The years 1860-80 were significant and crucial for the Mennonites of Ukraine. Religious life underwent great changes. A certain integration of the Mennonites coming from various backgrounds had taken place, and the later immigrant groups had transplanted from Germany to Ukraine elements of [[Pietism|Pietism]] that penetrated the whole like a leaven. The separation of the [[Kleine Gemeinde|Kleine Gemeinde]], led by [[Reimer, Klaas (1770-1837)|Klaas Reimer]] early in the 19th century in the Molotschna settlement, resulted from a protest toward certain adjustments and progress. Gradually, however, [[Pietism|pietistic]] influences such as the support of the St. Petersburg Bible Society, evangelistic efforts, mission festivals, abstinence, got a foothold in the brotherhood although they were promoted only by a minority. The South German Pietist Eduard Wüst, serving an independent pietistic congregation next to the Molotschna settlement, made a great impact on the Mennonites of the Molotschna. A somewhat similar influence was exerted in the Chortitza settlement by the Baptist [[Oncken, Johann Gerhard (1800-1884)|J. G. Oncken]] of Hamburg, Germany. All this not only influenced a large segment of the Mennonites of Ukraine, but also led to schisms culminating in the establishment of the [[Mennonite Brethren Church|Mennonite Brethren]], [[Krimmer Mennonite Brethren|Krimmer Mennonite Brethren]], [[Temple Society|Templers]] or Friends of Jerusalem, Hermann Peters group ([[Apostolische Brüdergemeinde|Apostolische Brüdergemeinde]]), and the movement of A. Peters, who led a group to Central Asia to meet the Lord at a specifically designated place. Among these separating groups only the Mennonite Brethren secured a significant number of followers among the Mennonites and made an outstanding impact on the total Mennonite brotherhood of Russia and later in South and [[North America|North America]]. Only this group spread to nearly all daughter settlements of Russia beyond Ukraine, while the others remained restricted to certain settlements. The Mennonite Brethren strongly emphasized [[Evangelism|evangelism]], [[Mission (Missiology)|missions]], [[Abstinence|abstinence]], and [[Baptism|baptism]] by [[Immersion|immersion]]. Particularly through the former two aspects they served as a leaven in the total brotherhood, while through the last point they established a sharp demarcation line which limited contact with the mother group and others primarily to converts to the Mennonite Brethren. The influence of [[Pietism|Pietism]], although it caused some schisms, also wholesomely leavened the Mennonite brotherhood. Wüst and other evangelistic and pietistic leaders had many friends and followers among the Mennonite brotherhood of Russia around 1860, some of whom were Johann Harder, Bernhard Harder, [[Lenzmann, August (1823-1877)|August Lenzmann]], and [[Jansen, Cornelius (1822-1894)|Cornelius Jansen]]. These felt it to be their duty to remain within the brotherhood and revive and strengthen its spiritual life. An outstanding evangelist, educator, and pioneer writer was Bernhard Harder. | <h3>Religious Life and Migrations</h3> The years 1860-80 were significant and crucial for the Mennonites of Ukraine. Religious life underwent great changes. A certain integration of the Mennonites coming from various backgrounds had taken place, and the later immigrant groups had transplanted from Germany to Ukraine elements of [[Pietism|Pietism]] that penetrated the whole like a leaven. The separation of the [[Kleine Gemeinde|Kleine Gemeinde]], led by [[Reimer, Klaas (1770-1837)|Klaas Reimer]] early in the 19th century in the Molotschna settlement, resulted from a protest toward certain adjustments and progress. Gradually, however, [[Pietism|pietistic]] influences such as the support of the St. Petersburg Bible Society, evangelistic efforts, mission festivals, abstinence, got a foothold in the brotherhood although they were promoted only by a minority. The South German Pietist Eduard Wüst, serving an independent pietistic congregation next to the Molotschna settlement, made a great impact on the Mennonites of the Molotschna. A somewhat similar influence was exerted in the Chortitza settlement by the Baptist [[Oncken, Johann Gerhard (1800-1884)|J. G. Oncken]] of Hamburg, Germany. All this not only influenced a large segment of the Mennonites of Ukraine, but also led to schisms culminating in the establishment of the [[Mennonite Brethren Church|Mennonite Brethren]], [[Krimmer Mennonite Brethren|Krimmer Mennonite Brethren]], [[Temple Society|Templers]] or Friends of Jerusalem, Hermann Peters group ([[Apostolische Brüdergemeinde|Apostolische Brüdergemeinde]]), and the movement of A. Peters, who led a group to Central Asia to meet the Lord at a specifically designated place. Among these separating groups only the Mennonite Brethren secured a significant number of followers among the Mennonites and made an outstanding impact on the total Mennonite brotherhood of Russia and later in South and [[North America|North America]]. Only this group spread to nearly all daughter settlements of Russia beyond Ukraine, while the others remained restricted to certain settlements. The Mennonite Brethren strongly emphasized [[Evangelism|evangelism]], [[Mission (Missiology)|missions]], [[Abstinence|abstinence]], and [[Baptism|baptism]] by [[Immersion|immersion]]. Particularly through the former two aspects they served as a leaven in the total brotherhood, while through the last point they established a sharp demarcation line which limited contact with the mother group and others primarily to converts to the Mennonite Brethren. The influence of [[Pietism|Pietism]], although it caused some schisms, also wholesomely leavened the Mennonite brotherhood. Wüst and other evangelistic and pietistic leaders had many friends and followers among the Mennonite brotherhood of Russia around 1860, some of whom were Johann Harder, Bernhard Harder, [[Lenzmann, August (1823-1877)|August Lenzmann]], and [[Jansen, Cornelius (1822-1894)|Cornelius Jansen]]. These felt it to be their duty to remain within the brotherhood and revive and strengthen its spiritual life. An outstanding evangelist, educator, and pioneer writer was Bernhard Harder. | ||

| − | Another significant development among the Mennonites of Ukraine was the new universal [[Conscription|conscription]] law that became known to the Mennonites around 1870, and resulted in a large | + | Another significant development among the Mennonites of Ukraine was the new universal [[Conscription|conscription]] law that became known to the Mennonites around 1870, and resulted in a large immigration to North America 1873-80. One of the chief promoters of this emigration for conscience' sake was Cornelius Jansen, supported by men like [[Buller, Jacob (1827-1901)|Jacob Buller]] and [[Gaeddert, Dietrich (1837-1900)|Dietrich Gaeddert]] of Alexanderwohl, [[Wiebe, Gerhard (1827-1900)|Gerhard Wiebe]] and [[Wiebe, Johann (1837-1905)|Johann Wiebe]] of [[Bergthal Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Bergthal]] and [[Fürstenland Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Fürstenland]], both daughter settlements of Chortitza, and Mennonite representatives form Russian Poland and Prussia. This resulted in the first and up to that time the largest Mennonite migration on record. Some 10,000 Mennonites primarily of the Molotschna settlement, Russian Poland, [[Galicia (Poland & Ukraine)|Galicia]], and Prussia, settled in the prairie states of the [[United States of America|United States]], while some 8,000 Mennonites of Chortitza and its two daughter settlements founded a new home in the [[East Reserve (Manitoba, Canada)|East]] and [[West Reserve (Manitoba, Canada)|West Reserves]] of [[Manitoba (Canada)|Manitoba]]. Those remaining in Russia accepted the responsibility of doing work in [[Forsteidienst|forestry service]] beginning in 1880 and in [[World War (1914-1918)|World War I]] in hospital service. Once again the threat to the principle of nonresistance had alarmed the Mennonites and caused some to leave the country and others to grow into a more active participation and sense of responsibility in the affairs of the country in which they lived. The challenging alternative service program of the Mennonites of Russia had a wholesome influence on the total brotherhood and also caused a closer co-operation between the main groups that had drifted apart since 1860. Again it was Ukraine which furnished leadership in this significant program in which Mennonite settlements of the remotest areas benefited. |

<h3>The Revolution and After (1917-43)</h3> With the outbreak of World War I the decline and the ultimate destruction of Mennonite settlements of Ukraine was ushered in. A severe anti-German feeling which had been previously active in the Russianization policy of the foreign settlers of Russian now sought to destroy the prosperous settlements by confiscating their property and removing them to uninhabited areas. Only the outbreak of the [[Russian Revolution and Civil War|Revolution in 1917]] prevented this act. In a way the Mennonites greeted the new day in which the liberal and democratic government under Kerensky was to establish an era of justice for all. However, the Revolution proved to be another and a more radical step toward the annihilation of all that had been achieved by the Mennonites in more than 100 years. First a civil war, typhoid fever, confiscation of property, starvation, and plundering by irregulars at times led by men like [[Makhno, Nestor (1888-1934)|Makhno]] or individual bandits caused almost unbearable hardships to the settlements of Ukraine which suffered much more under them than those located in other parts of Russia. Many of the owners of industries and large estates were put to death by bandits after radical Marxian ideas became prevalent, which ideas were often reinforced by a lingering anti-German feeling. | <h3>The Revolution and After (1917-43)</h3> With the outbreak of World War I the decline and the ultimate destruction of Mennonite settlements of Ukraine was ushered in. A severe anti-German feeling which had been previously active in the Russianization policy of the foreign settlers of Russian now sought to destroy the prosperous settlements by confiscating their property and removing them to uninhabited areas. Only the outbreak of the [[Russian Revolution and Civil War|Revolution in 1917]] prevented this act. In a way the Mennonites greeted the new day in which the liberal and democratic government under Kerensky was to establish an era of justice for all. However, the Revolution proved to be another and a more radical step toward the annihilation of all that had been achieved by the Mennonites in more than 100 years. First a civil war, typhoid fever, confiscation of property, starvation, and plundering by irregulars at times led by men like [[Makhno, Nestor (1888-1934)|Makhno]] or individual bandits caused almost unbearable hardships to the settlements of Ukraine which suffered much more under them than those located in other parts of Russia. Many of the owners of industries and large estates were put to death by bandits after radical Marxian ideas became prevalent, which ideas were often reinforced by a lingering anti-German feeling. | ||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

During the German occupation of large parts of Russia in 1941-43, the Mennonite settlements of Ukraine and many others were in the hands of the occupational authorities. Although a large percentage of the population had been evacuated before this to Asiatic and Northern Russia, for those who remained in Ukraine a revival of some aspects of the cultural and religious life took place for a time. Religious services were introduced, ministers were elected, and baptismal services took place. The old school system was revived. But all of this was of short duration. The German authorities themselves began repressive measures against the church parallel to what was going on in Germany at the time under Hitler. | During the German occupation of large parts of Russia in 1941-43, the Mennonite settlements of Ukraine and many others were in the hands of the occupational authorities. Although a large percentage of the population had been evacuated before this to Asiatic and Northern Russia, for those who remained in Ukraine a revival of some aspects of the cultural and religious life took place for a time. Religious services were introduced, ministers were elected, and baptismal services took place. The old school system was revived. But all of this was of short duration. The German authorities themselves began repressive measures against the church parallel to what was going on in Germany at the time under Hitler. | ||

| − | In the fall of 1943 Germany began to evacuate westward the remaining German, including Mennonite, population of Ukraine. During the middle of September the Halbstadt district of the Molotschna settlement was evacuated by wagons. In October the Chortitza settlement followed by trains, and in November Zagradovka. The population of other settlements was similarly evacuated. The railroad transports consisted as a rule of 50 freight cars each occupied by approximately 1,200 persons. Many of the evacuees, particularly those traveling by wagons, suffered severely from the attacking Russian army and the partisans. The German government planned to settle the Russo-German population, including the Mennonites, in East Germany, some of them in the Warthegau, the territory annexed from Poland along the Vistula River, south of the general area from which the Mennonites had left for Russia 150 years earlier. But many were still in camps, not yet in the area, when the advancing Russian army blasted all such plans. It is estimated that the remaining Mennonite population of Ukraine transported to Germany was about 35,000. In the Warthegau most Mennonites were made German citizens by a mass decree, and most surviving Mennonite men were drafted into the German army. | + | In the fall of 1943, Germany began to evacuate westward the remaining German, including Mennonite, population of Ukraine. During the middle of September the Halbstadt district of the Molotschna settlement was evacuated by wagons. In October the Chortitza settlement followed by trains, and in November Zagradovka. The population of other settlements was similarly evacuated. The railroad transports consisted as a rule of 50 freight cars each occupied by approximately 1,200 persons. Many of the evacuees, particularly those traveling by wagons, suffered severely from the attacking Russian army and the partisans. The German government planned to settle the Russo-German population, including the Mennonites, in East Germany, some of them in the Warthegau, the territory annexed from Poland along the Vistula River, south of the general area from which the Mennonites had left for Russia 150 years earlier. But many were still in camps, not yet in the area, when the advancing Russian army blasted all such plans. It is estimated that the remaining Mennonite population of Ukraine transported to Germany was about 35,000. In the Warthegau most Mennonites were made German citizens by a mass decree, and most surviving Mennonite men were drafted into the German army. |

When, in January 1945, the Russian army entered this territory on its march westward, the Mennonites tried to flee westward toward the provinces of [[Saxony|Saxony]], [[Thuringia (Germany)|Thuringia]], Mecklenburg, Hannover, and [[Bayern Federal State (Germany)|Bavaria]]. Most of those who found themselves in the Russian occupied zone of Germany at the end of the war were forcibly repatriated or sent back to Russia. It has been estimated that this must have been nearly two thirds of the 35,000 Mennonites who had been transported to Germany, which would be over 20,000. Many family members were again separated. The 12,000-14,000 who escaped to western Germany found new homes in Canada and South America, with the help of the [[Mennonite Central Committee (International)|Mennonite Central Committee]], the [[International Refugee Organization (IRO)|International Refugee Organization]] (IRO), and the [[Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization|Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization]]. The full story of those who were sent back is not yet known. Most of them, however, were sent to northern and [[Asiatic Russia|Asiatic Russia]]. Recently it has become easier for citizens of the Soviet Union to move about. Some family members from various settlements of Ukraine scattered during the waves of exile, evacuation, and repatriation have found each other. Some have even visited their home communities in Ukraine and reported the devastation caused by the scorched earth policy of [[World War (1939-1945) - Soviet Union|World War II]]. | When, in January 1945, the Russian army entered this territory on its march westward, the Mennonites tried to flee westward toward the provinces of [[Saxony|Saxony]], [[Thuringia (Germany)|Thuringia]], Mecklenburg, Hannover, and [[Bayern Federal State (Germany)|Bavaria]]. Most of those who found themselves in the Russian occupied zone of Germany at the end of the war were forcibly repatriated or sent back to Russia. It has been estimated that this must have been nearly two thirds of the 35,000 Mennonites who had been transported to Germany, which would be over 20,000. Many family members were again separated. The 12,000-14,000 who escaped to western Germany found new homes in Canada and South America, with the help of the [[Mennonite Central Committee (International)|Mennonite Central Committee]], the [[International Refugee Organization (IRO)|International Refugee Organization]] (IRO), and the [[Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization|Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization]]. The full story of those who were sent back is not yet known. Most of them, however, were sent to northern and [[Asiatic Russia|Asiatic Russia]]. Recently it has become easier for citizens of the Soviet Union to move about. Some family members from various settlements of Ukraine scattered during the waves of exile, evacuation, and repatriation have found each other. Some have even visited their home communities in Ukraine and reported the devastation caused by the scorched earth policy of [[World War (1939-1945) - Soviet Union|World War II]]. | ||

Revision as of 17:37, 25 January 2016

Introduction

Ukraine (Russian, Ukraina), formerly the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, a republic of the USSR located in the southwest, on the north shore of the Black Sea (Crimea not included), consisted of 171,770 square miles with a population of 30,960,221 (1939) which was increased during World War II to 213,473 square miles and a population of 40,600,000 (1950), (in 2005 the country, independent since 1991, consisted of 233,090 square miles with an estimated population of 46,481,000). The name Ukraine is popularly believed to mean "borderland," but Ukrainian nationalists interpret it to mean "cut off from something in one’s possession" (Slavonic Encyclopedia: 1, 325). The story of Ukraine consists of chapters of nationalism, oppression, heroism, and victory. Kiev, the capital of Ukraine, played a significant role in the early history of Russia. The Cossacks became the protectors and defenders of Ukraine against the Mongolian occupants and invaders.

In Mennonite history the final subjugation of Ukraine by Catherine II (Empress of Russia, 1762-96) played a significant role. She had Grigori Alexandrovich Potemkin colonize and settle Ukraine by a transfer of population from central Russia and the invitation of foreign settlers to Russia. This has been presented in greater detail in the article Russia.

Before World War I Ukraine had become the chief producer of grains, particularly wheat. The Mennonites contributed to making Ukraine the breadbasket of Europe by introducing new methods of agriculture and by developing flour industries in various areas. In 1955 however, Ukraine produced only 14 percent of the total Soviet output of grain, having become more important in industrial pursuits. The iron located near Krivoi Rog, and manganese at Nikopol, which utilize the coal of the Don Region, are significant for industry. Hydroelectric power is produced at the great Dneprostroi Dam in the region of the former Mennonite settlement of Chortitza. Some of the major industrial centers and cities are Kiev, Kharkov, Odessa, Dnepropetrovsk (formerly Ekaterinoslav), Zaporizhia (formerly Alexandrovsk), and Chortitza. The foundation for some of these industrial centers, e.g., the last two, was laid by Mennonites. The reason for the shift from agriculture to industry is the fact that the Soviet Union had opened up vast territories for agriculture east of the Ural Mountains and is industrializing the country rapidly, which results in a greater emphasis on the latter in Ukraine.

Mennonite Settlements

Ukraine was a major attraction in 1789-1840 not only for the Mennonites, but also for other foreign settlers, particularly from Germany. Two of the major German settlements were those located in the region of Odessa, and in the Molotschna with a center named Prischib. The Mennonites were in touch with these settlements and this interchange of cultural ideas and stimulation was of mutual benefit.

The most significant provinces of Ukraine for the Mennonites were Ekaterinoslav, Taurida, Kherson, and Kharkov. In Ekaterinoslav the two mother settlements of Chortitza and Molotschna were located. Of the 50 or more Mennonite daughter settlements established in Russia 20 were located in Ekaterinoslav, six in Taurida, four in Kherson, and two in Kharkov, making a total of 32 in Ukraine, not counting the many large private estates. Of the approximately 120,000 Mennonites located in Russia before World War I, about 75,000 lived in Ukraine (Ehrt, 153); and of the approximately 3,000,000 acres (see ME I, 25) of land owned by the Mennonites of Russia at that time, approximately half (Ehrt, 83) was located in Ukraine. This does not include the Mennonite population and land located in the Crimea, the Caucasus, the Don Region along the Volga River, or in central Russia. The major Mennonite industrial and business centers were located in Ukraine. This was also true of educational institutions and religious and cultural centers.

As long as there was land available in Ukraine, the Mennonites aimed to establish daughter settlements in the proximity of the two mother settlements of Chortitza and Molotschna. However some settlers soon moved beyond Ukraine. Around 1862 Mennonites of Ukraine found their way to the Crimea, which remained a center of attraction. Here the Mennonites acquired more than 100,000 acres of land located in villages and large estates. Another early settlement was in the Kuban at the foothills of the Caucasian Mountains where the Mennonite Brethren and the Templers received special permission for settlement. Molotschna chiliasts under the leadership of Abraham Peters went to Central Asia to meet the Lord and established the settlement of Auli-Alta in 1882. Toward the end of the century Mennonites of Ukraine established themselves in Neu-Samara in 1890; Davlekanovo in 1894; Orenburg in 1894; and Siberia in 1898.

In this program of expansion the mother settlements of Ukraine, particularly their respective centers, such as Chortitza, Halbstadt, Orloff, and Gnadenfeld, maintained their importance as economic, cultural, and religious centers. The churches established in many of the new settlements remained subsidiaries of the mother churches in Ukraine for a generation. In spite of the distance, cultural and religious ties kept the daughter settlements attached to their mother settlements. In many instances the mother settlement financed and supervised the settlement of its landless population. As a rule in the layout of the villages, the construction of the homes, and the organization of cultural and religious life in the new settlements, they closely resembled the mother settlement, although an adjustment to geographic, climatic, and other local conditions was noticeable.

The increase in large estate owners, who were particularly numerous in Ukraine, is a chapter in itself. Johann Cornies in the early days, and the Sudermann, Dyck and Schmidt families in the later days, owned large estates. A total of 384 large estates comprised three tenths of the land owned by Mennonites in Russia. The largest estate in Ukraine was a ranch of 50,000 acres. (ME I, 25).

The following is a table of the two mother settlements of Ukraine, Chortitza and Molotschna, and the daughter settlements of these two that were established in Ukraine. (For a complete list of all settlements, see the article Russia.)

| A. Mother Settlements | |||||||

| Name | Province | Founded | Villages | Acreage | Population | ||

| 1. | Chortitza | Ekaterinoslav | 1789 ff. | 19 | 1789: 89,100 1917: 405,000 | 1819: 2,888 1941: 13,965 | |

| 2. | Molotschna | Taurida | 1804 ff. | 60 | 1835: 324,000 | 1835: 6,000 1926: 17,347 | |

| B. Daughter Settlements | |||||||

| Name | Province | Mother Settlement | Founded | Villages | Acreage | Population | |

| 1. | Bergthal | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1836-52 | 5 | 30,000 | 1874: 3,000 |

| 2. | Hutterthal | Taurida | Radichev | 1843 | 1 | ||

| 3. | Jewish Settlement (Judenplan) | Kherson | Chortitza | 1847 | 6 | 5-6 families in each village | |

| 4. | Johannesruh | Taurida | Hutterthal | 1853 | 1 | ||

| 5. | Hutterdorf | Taurida | Hutterthal | 1857 | 1 | ||

| 6. | Neu-Hutterthal | Taurida | 1857 | 1 | |||

| 7. | Tchornoglaz | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1860 | 1 | 2,700 | 100 |

| 8. | Crimea | Taurida | Molotschna | 1862 ff. | ca.25 & estates | 1929: 108,000 | 1926: 4,817 |

| 9. | Fürstenland | Taurida | Chortitza | 1864-70 | 7 | 19,000 | 1874: 1,100 |

| 10. | Borozenko | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1865-66 | 6 | 18,000 | 1910: 600 |

| 11. | Friedensfeld (Miropol) | Ekaterinoslav | Molotschna | 1867 | 1 | 5,400 | |

| 12. | Brazol (Schönfeld) | Ekaterinoslav | Molotschna | 1868 | 4 & estates | 1868: 14,000 1910: 187,000 | 1917: 2,000 |

| 13. | Neu-Schönwiese (Dmitrovka) | Ekaterinoslav | Schönwiese-Chortitza | 1868 | 1 | 3,788 | |

| 14. | Yazykovo (Nikolaifeld) | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1869 | 6 | 23,315 | 1930: 2,200 |

| 15. | Nepluyevka | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1870 | 2 | 10,800 | 1910: 550 |

| 16. | Andreasfeld | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1870 | 3 | 10,620 | |

| 17. | Baratov | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1872 | 2 (4) | 1872: 9,800 | 1905: 2,569 |

| 18. | Zagradovka | Kherson | Molotschna | 1871 | 16 | 57,445 | 1922: 5,429 |

| 19. | Schlachtin | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1874 | 2 | 10,800 | 1910: 1,000 |

| 20. | Neu-Rosengart | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1878 | 2 | 1,800 | 1910: 250 |

| 21. | Wiesenfeld | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1880 | 1 | ||

| 22. | Memrik | Ekaterinoslav | Molotschna | 1885 | 10 | 32,400 | 1,367 |

| 23. | Alexandropol | Ekaterinoslav | Molotschna | 1888 | 1 | 15 families | |

| 24. | Samoylovka | Kharkov | Molotschna | 1888 | 2 | 1905: 239 | |

| 25. | Miloradovka | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1889 | 2 | 5,670 | 1910: 200 |

| 26. | Ignatyevo | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1889-90 | 7 | 38,132 | 1910: 1,400 |

| 27. | Naumenko | Kharkov | Chortitza | 1890 | 4 (3) | 14,350 | 1905: 700 |

| 28. | Borissovo | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1892 | 2 | 13,770 | 1910: 400 |

| 29. | Trubetskoye | Kherson | Molotschna | 1904 | 2 | 118,800 (?) | 400 |

| 30. | Kuzmitsky (Alexandrovka) | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1 | 1910: 4,860 | 1910: 200 | |

| 31. | Eugenfeld | Ekaterinoslav | Chortitza | 1 | |||

| 32. | Alexeyfeld | Kherson | Molotschna | 1 | |||

Cultural Achievements

The contributions that the Mennonites made in Russia, and their cultural achievement, had their foundation in the settlements of Ukraine. Here the village settlement and administration as well as the cultural and religious life were developed and transplanted to other areas. The Chortitza and Molotschna settlements developed a pattern of education that spread over Russia and exerted a strong influence on some of the Mennonites in North and South America (see Education among the Mennonites of Russia). The agricultural and industrial developments of the Mennonites of Ukraine were also decisive for all the daughter settlements in the rest of Russia. Outposts of industries such as factories and flourmills were established in Mennonite and non-Mennonite communities, many of which became the attraction of businessmen and workers seeking employment (see articles Millerovo, New York). Ukraine with its fertile black soil (chernozem) gave the Mennonites the extraordinary opportunity of experimenting in agriculture and contributing to the development of hard winter wheat, one of the most desirable export items. In the 1870's this wheat was transplanted from the steppes of Ukraine to the prairies of Kansas. The fact that Ukraine was agriculturally and industrially an undeveloped territory at the time the Mennonites settled there gave them an excellent opportunity to fulfill a service in this area that they discharged with great success. Again it must be pointed out that they were only a minority among the numerous German settlers of Ukraine who helped to develop this country in the realm of agriculture and industry. (See also articles Industry, Business, and Agriculture.)

Religious Life and Migrations

The years 1860-80 were significant and crucial for the Mennonites of Ukraine. Religious life underwent great changes. A certain integration of the Mennonites coming from various backgrounds had taken place, and the later immigrant groups had transplanted from Germany to Ukraine elements of Pietism that penetrated the whole like a leaven. The separation of the Kleine Gemeinde, led by Klaas Reimer early in the 19th century in the Molotschna settlement, resulted from a protest toward certain adjustments and progress. Gradually, however, pietistic influences such as the support of the St. Petersburg Bible Society, evangelistic efforts, mission festivals, abstinence, got a foothold in the brotherhood although they were promoted only by a minority. The South German Pietist Eduard Wüst, serving an independent pietistic congregation next to the Molotschna settlement, made a great impact on the Mennonites of the Molotschna. A somewhat similar influence was exerted in the Chortitza settlement by the Baptist J. G. Oncken of Hamburg, Germany. All this not only influenced a large segment of the Mennonites of Ukraine, but also led to schisms culminating in the establishment of the Mennonite Brethren, Krimmer Mennonite Brethren, Templers or Friends of Jerusalem, Hermann Peters group (Apostolische Brüdergemeinde), and the movement of A. Peters, who led a group to Central Asia to meet the Lord at a specifically designated place. Among these separating groups only the Mennonite Brethren secured a significant number of followers among the Mennonites and made an outstanding impact on the total Mennonite brotherhood of Russia and later in South and North America. Only this group spread to nearly all daughter settlements of Russia beyond Ukraine, while the others remained restricted to certain settlements. The Mennonite Brethren strongly emphasized evangelism, missions, abstinence, and baptism by immersion. Particularly through the former two aspects they served as a leaven in the total brotherhood, while through the last point they established a sharp demarcation line which limited contact with the mother group and others primarily to converts to the Mennonite Brethren. The influence of Pietism, although it caused some schisms, also wholesomely leavened the Mennonite brotherhood. Wüst and other evangelistic and pietistic leaders had many friends and followers among the Mennonite brotherhood of Russia around 1860, some of whom were Johann Harder, Bernhard Harder, August Lenzmann, and Cornelius Jansen. These felt it to be their duty to remain within the brotherhood and revive and strengthen its spiritual life. An outstanding evangelist, educator, and pioneer writer was Bernhard Harder.

Another significant development among the Mennonites of Ukraine was the new universal conscription law that became known to the Mennonites around 1870, and resulted in a large immigration to North America 1873-80. One of the chief promoters of this emigration for conscience' sake was Cornelius Jansen, supported by men like Jacob Buller and Dietrich Gaeddert of Alexanderwohl, Gerhard Wiebe and Johann Wiebe of Bergthal and Fürstenland, both daughter settlements of Chortitza, and Mennonite representatives form Russian Poland and Prussia. This resulted in the first and up to that time the largest Mennonite migration on record. Some 10,000 Mennonites primarily of the Molotschna settlement, Russian Poland, Galicia, and Prussia, settled in the prairie states of the United States, while some 8,000 Mennonites of Chortitza and its two daughter settlements founded a new home in the East and West Reserves of Manitoba. Those remaining in Russia accepted the responsibility of doing work in forestry service beginning in 1880 and in World War I in hospital service. Once again the threat to the principle of nonresistance had alarmed the Mennonites and caused some to leave the country and others to grow into a more active participation and sense of responsibility in the affairs of the country in which they lived. The challenging alternative service program of the Mennonites of Russia had a wholesome influence on the total brotherhood and also caused a closer co-operation between the main groups that had drifted apart since 1860. Again it was Ukraine which furnished leadership in this significant program in which Mennonite settlements of the remotest areas benefited.

The Revolution and After (1917-43)

With the outbreak of World War I the decline and the ultimate destruction of Mennonite settlements of Ukraine was ushered in. A severe anti-German feeling which had been previously active in the Russianization policy of the foreign settlers of Russian now sought to destroy the prosperous settlements by confiscating their property and removing them to uninhabited areas. Only the outbreak of the Revolution in 1917 prevented this act. In a way the Mennonites greeted the new day in which the liberal and democratic government under Kerensky was to establish an era of justice for all. However, the Revolution proved to be another and a more radical step toward the annihilation of all that had been achieved by the Mennonites in more than 100 years. First a civil war, typhoid fever, confiscation of property, starvation, and plundering by irregulars at times led by men like Makhno or individual bandits caused almost unbearable hardships to the settlements of Ukraine which suffered much more under them than those located in other parts of Russia. Many of the owners of industries and large estates were put to death by bandits after radical Marxian ideas became prevalent, which ideas were often reinforced by a lingering anti-German feeling.

In March 1917 the Revolution began which was to end World War I for Russia. From March until November of that year Ukraine was under the temporary government of Kerensky, after which the radical Bolsheviks took over the government, remaining in power in Ukraine from November 1917 to April 1918 when the German army occupied Ukraine. In November 1918 the German army withdrew and many of the Mennonite settlements were occupied by Makhno's bands until July 1919, at which time the army of Denikin took over and occupied the territory until October 1919. From October 1919 until January 1920 Makhno and his bands reigned again until the Bolsheviks returned. In June 1920 General Peter Wrangel tried once more, as Denikin had before him, to restore the Czarist government. In the fall of 1920 this dream was shattered forever and the Communist regime took over.

All Ukrainian Mennonite settlements and estates suffered severely during these trying years. Several whole villages were slaughtered by Makhno's bandits. Among them were Eichenfeld and certain villages of Zagradovka. In some instances Mennonite young men under the guidance of officers of the German occupation army which withdrew, had organized a "Selbstschutz" to protect their settlements and particularly the lives of their family members, during the time when there was no established government and there was imminent danger that roving bandits would molest the settlements. A number of young men also joined the forces of the White army, which was defeated by the Red army. Some 62 of the surviving young men came to America via Constantinople. As a rule this self-defense of the Mennonites of Ukraine was not approved of by the Mennonite authorities of the settlements, and in some cases may have provoked action by the Makhno irregulars.

Significant during these years of hardship and trial was the help given to the Mennonites of Ukraine by the American Mennonites administered through the American Mennonite Relief, and the Dutch Mennonites through their relief agency. Both agencies sent representatives to Russia. The food and clothing supplied distributed and the agricultural machinery that was made available, as well as the spiritual and moral support, were of great help. The U.S. government relief program, the American Relief Administration (ARA) also helped much.

Immediately after the establishment of order by the Communist regime, some hopeful Mennonites anticipated a more or less normal although modified economic and cultural life in the settlements. A gradual adjustment to the new regime became noticeable on the one hand, but also a realization on the other hand that the Communist program was too radical. Hence in 1923-27 and again in 1929-30 many thousands left Ukraine via Moscow and Riga in order to establish new homes in Canada. Those who were more optimistic formed organizations in order to represent their rights and interests under the new Soviet government. One of the most outstanding organizations was the Verband der Bürger Holländischer Herkunft (Union of Citizens of Dutch Ancestry). A conference called in Orloff in 1917 during the reign of Kerensky, the Allgemeiner Mennonitischer Kongress, was designed to regulate the total cultural life of the Mennonites of Ukraine. However, only two sessions could be held. The last Bundeskonferenz met as an All-Ukrainian Conference at Melitopol in 1926. At the risk of imprisonment and loss of life the leaders aimed to find a common platform to solve the problems facing them. Under the NEP (New Economic Policy) this was still possible. After Lenin's death in 1926, Stalin inaugurated a radical program of collectivization of all land by exiling the formerly more prosperous farmers (Kulaks), which affected the Mennonites deeply and caused the disruption and final annihilation of most of their cultural values in Ukraine. Two main waves of exile, one in 1929-30 and the second in 1937-38, reduced the Mennonite population of Ukraine considerably, especially the male part. Another wave of evacuation occurred when the German army invaded Ukraine in 1941. Chortitza is an illustration of what happened to the Mennonite population in 1929-38, when 1,456 people out of a total population of 11,666 (1918) were exiled and 1,281 were evacuated by the Russians eastward when the Germans approached in 1941. This evacuation of the German population was much more successful in the settlements east of the Dnieper, such as the Molotschna and many of the daughter settlements, than those west. The Dnieper formed a natural barrier for the invading German army that prevented the removal of the Chortitza Mennonites and gave the Russians enough time to remove a large portion of the Russo-German population east of the Dnieper. All men between the ages of 16 and 65 had been evacuated previously. However, some of the population of Halbstadt and Stulnevo fell into the hands of the approaching German army. The Soviet authorities still succeeded in evacuating one third of the remaining Molotschna population to Siberia before the German army reached the villages (G. Fast).

Further statistics of the Chortitza settlement acquired during the German occupation of Ukraine during World War II reveal that of the Chortitza settlement, 245 individuals were killed by Makhno's irregulars, and 30 died of starvation in 1921-22 and 1932-33. About one third of the land formerly owned and farmed by the Mennonites of Chortitza was turned over to the neighboring Russian population. All farming was done collectively. All churches were closed by 1935 and used as theaters, clubhouses, stables, or granaries. Conditions in other settlements were very similar.

During the German occupation of large parts of Russia in 1941-43, the Mennonite settlements of Ukraine and many others were in the hands of the occupational authorities. Although a large percentage of the population had been evacuated before this to Asiatic and Northern Russia, for those who remained in Ukraine a revival of some aspects of the cultural and religious life took place for a time. Religious services were introduced, ministers were elected, and baptismal services took place. The old school system was revived. But all of this was of short duration. The German authorities themselves began repressive measures against the church parallel to what was going on in Germany at the time under Hitler.

In the fall of 1943, Germany began to evacuate westward the remaining German, including Mennonite, population of Ukraine. During the middle of September the Halbstadt district of the Molotschna settlement was evacuated by wagons. In October the Chortitza settlement followed by trains, and in November Zagradovka. The population of other settlements was similarly evacuated. The railroad transports consisted as a rule of 50 freight cars each occupied by approximately 1,200 persons. Many of the evacuees, particularly those traveling by wagons, suffered severely from the attacking Russian army and the partisans. The German government planned to settle the Russo-German population, including the Mennonites, in East Germany, some of them in the Warthegau, the territory annexed from Poland along the Vistula River, south of the general area from which the Mennonites had left for Russia 150 years earlier. But many were still in camps, not yet in the area, when the advancing Russian army blasted all such plans. It is estimated that the remaining Mennonite population of Ukraine transported to Germany was about 35,000. In the Warthegau most Mennonites were made German citizens by a mass decree, and most surviving Mennonite men were drafted into the German army.

When, in January 1945, the Russian army entered this territory on its march westward, the Mennonites tried to flee westward toward the provinces of Saxony, Thuringia, Mecklenburg, Hannover, and Bavaria. Most of those who found themselves in the Russian occupied zone of Germany at the end of the war were forcibly repatriated or sent back to Russia. It has been estimated that this must have been nearly two thirds of the 35,000 Mennonites who had been transported to Germany, which would be over 20,000. Many family members were again separated. The 12,000-14,000 who escaped to western Germany found new homes in Canada and South America, with the help of the Mennonite Central Committee, the International Refugee Organization (IRO), and the Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization. The full story of those who were sent back is not yet known. Most of them, however, were sent to northern and Asiatic Russia. Recently it has become easier for citizens of the Soviet Union to move about. Some family members from various settlements of Ukraine scattered during the waves of exile, evacuation, and repatriation have found each other. Some have even visited their home communities in Ukraine and reported the devastation caused by the scorched earth policy of World War II.

The following information indicates that since the beginning of 1956, a few Mennonites have returned to their home communities in Ukraine. Marie Schellenberg from Siberia writes, "Since 13 January 1956, we are free to travel" (Der Bote [3 October 1956]: 7). In the same issue of Der Bote, D. and N. Vogt report that they were exiled to the Vologda Region in 1945 and that they returned to their own village of Schönhorst in the Chortitza settlement on 20 April 1956, where they were accepted in the Russian collective farm, although Vogt was 70 years old. They report further that the members of the collective farm were prosperous and that the children of the Vogts also plan to return. Mrs. Paul Neufeld reports that her daughter Marus lives in their home village of Nieder-Chortitza, Chortitza settlement, and that she and her daughter Hilda were also planning to return (Der Bote [29 August 1956]: 7).

More Mennonites may find their way back to Ukraine and even to their former homes, although a mass reoccupation of Mennonite villages is impossible since the land is all collectivized and the villages resettled. It is also possible that a few families, particularly where one spouse was Russian, remained in Ukraine when the German army evacuated the Mennonite population in 1943. News has been received that in 1955 a congregation had been begun in the former Memrik colony, with regular services. In spite of this it is very doubtful that there will be a general large-scale return of Mennonite families to their former homes in Ukraine. Many of the older generation have passed from the scene or do not have the possibility of returning, and for the younger generation Ukraine is no longer "home."

The former Mennonite population of Ukraine is today dispersed to many parts of the earth. It found its way to the prairie states and provinces of the United States and Canada in 1874-80 when some 18,000 migrated because of the principle of nonresistance. In 1923-30 some 25,000 left the Soviet Ukraine to find new homes in Canada and South America, and after World War II some 14,000 joined their brethren in Canada and in South America. The remaining former Mennonite population of Ukraine is today found scattered in Northern European Russia - Vologda Region and Arkhangelsk Region, and particularly in the northeast regions of Molotov, Tyumen, Sverdlovsk, and Chelyabinsk; also the Kazakh SSR in Soviet Central Asia, Semipalatinsk, Karaganda, and Akmolinsk, and the areas of the older Mennonite settlements and regions of Omsk, Tomsk, Novosibirsk, and Slavgorod, but also in the far southern area of Tadzhikistan. Many were also sent to the various parts of Eastern Siberia. (See also Soviet Central Asia.)

Ukraine was the cradle of the Mennonite settlements and culture in Russia. For 150 years the Mennonites had a unique opportunity to realize their vision and the contribution they could make in an environment that offered unusual opportunities for economic and cultural pioneering. Slavic and nomadic neighbors learned much through the advanced agricultural methods of the Mennonites. Many thousands of Russian young men and women were trained by working and living with the Mennonites in their homes and villages. The Evangelical movement resulting in the founding of the Evangelical Christians and Baptists was greatly influenced by the Mennonites of Ukraine, which is illustrated by the fact that there is co-operation between the two at this time and that the Mennonites are being paid back in the form of being taken into the congregations and fellowship of these groups wherever they are located close to Baptist churches.

2010 Update

In 2009 the following Anabaptist groups worshiped in Ukraine:

| Denomination | Members | Congregations |

|---|---|---|

| Christian Union of Mennonite Churches in Ukraine

Presiding Officer: Jacob Tiessen, Chairman | 180 | 4 |

| Evangelical Mennonite Church (Beachy Amish Church - Ukraine)

Contact: David Peachey | 101 | 3 |

Bibliography

Arkhymovych, O. "Grain Crops in the Ukraine." Ukrainian Review II, Munich, 1956.

Armstrong, John A. Ukrainian Nationalism. New York, 1955.

Der Bote.

Die Mennoniten-Gemeinden in Russland wahrend der Kriegs- und Revolutionsjahre 1914-1920. Heilbronn, 1921.

Ehrt, Adolf. Das Mennonitentum in Russland. Berlin, 1932.

Eisenach, George J. Pietism and the Russian Germans in the United States. Berne, 1948.

Epp, D. H. Die Chortitzer Mennoniten. Odessa, 1889.

Epp, D. H. Johann Cornies. Rosthern, 1946.

Friesen, Peter M. Die Alt-Evangelische Mennonitische Brüderschaft in Russland (1789-1910) im Rahmen der mennonitischen Gesamtgeschichte. Halbstadt: Verlagsgesellschaft "Raduga", 1911.

Froese, Leonhard. Das pädagogische Kultursystem der mennonitischen Siedlungsgruppe in Russland. Göttingen, 1949.

Glowinskyj, E. "Agriculture in the Ukraine."

Goerz, H. Die Molotschnaer Ansiedlung. Steinbach, 1950-51.

Goerz, H. Memrik. Rosthern, 1954.

Hildebrandt, P. Erste Auswanderung der Mennoniten aus dem Danziger Gebiet nach Südrussland. Halbstadt, 1888.

Isaac, Franz. Mennonites: Die Molotschnaer Mennoniten. Halbstadt, 1908.

Klaus, A. Unsere Kolonien. Odessa, 1887.

Krahn, Cornelius. "Russian Baptists and Mennonites." Mennonite Life XI (July 1956): 99.

Lohrenz, Gerhard. Sagradovka. Rosthern, 1947.

Manning, Clarence. The Story of the Ukraine. New York, 1947.

Mennonite Life.

Mennonitisches Jahrbuch, ed. Heinrich Dirks. Gross-Tokmak, 1901-14.

Mennonitische Rundschau.

Neufeld, D. Mennonitentum in der Ukraine Schicksalgeschichte Sagradowkas. Emden, 1922.

Petzholdt, Alexander. eise im westlichen und südlichen europäischen Russland im Jahre 1855. Leipzig, 1864.

Polonska-Vasylenko, N. D. "The Settlement of the Southern Ukraine (1750-1775)." The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the United States. New York, 1955.

Quiring, Jacob. Die Mundart von Chortitza in Süd-Russland. Munich, 1928.

Reimer, Gustav, and G. R. Gaeddert. Exiled by the Czar. Newton, 1956.

Rempel, D. G. "The Mennonite Colonies in New Russia . . ." Unpublished doctoral dissertation at Stanford University, 1933.

Shankowsky, "Nazi Occupation in Ukraine." Ukrainian Review II. London, 1955.

Smith, C. Henry. The Coming of the Russian Mennonites. Berne, 1927.

Smith, C. Henry. The Story of the Mennonites. Newton, 1957.

Stumpp, K. Bericht über das Gebiet Chortitza. Berlin, 1943.

Stumpp, K. Bericht über das Gebiet Kronau-Orloff. Berlin, 1943.

Töws, Gerhard. Schönfeld. Winnipeg, 1939.

Unruh, A. H. Die Geschichte der Mennoniten-Brüdergemeinde 1860-1954. Winnipeg, 1954.

Unruh, Benjamin H. Die niederländisch-niederdeutschen Hintergründe der mennonitischen Ostwanderungen im 16., 18. und 19. Jahrhundert. Karlsruhe-Rüppurr: Selbstverlag, 1955.

Wiseley, W. C. "The German Settlement of the 'incorporated territory' of the Wartheland and Danzig-West Prussia, 1939-1945." Ph.D. dissertation, London, 1955.

Yakovlev, B. Concentration Camps in the USSR (Russian). Münich, 1955.

| Author(s) | Cornelius Krahn |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1959 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Krahn, Cornelius. "Ukraine." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1959. Web. 1 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Ukraine&oldid=133324.

APA style

Krahn, Cornelius. (1959). Ukraine. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 1 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Ukraine&oldid=133324.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 4, pp. 763-769. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.