Difference between revisions of "Kansas (USA)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

SamSteiner (talk | contribs) |

SamSteiner (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

In the midst of the Mennonite migration from Russia to Kansas A. E. Touzalin, land commissioner for the Santa Fe, became agent of the [[Burlington Railroad|Burlington and Quincy Railroad]]. In this capacity he made considerable effort to divert to [[Nebraska (USA)|Nebraska]] the immigrants which he had solicited for Kansas, since the Burlington ran through Nebraska. The Santa Fe secured [[Schmidt, C. B. (Carl Bernhard) (1843-1921?)|C. B. Schmidt]] as agent, who immediately contacted the Mennonites. | In the midst of the Mennonite migration from Russia to Kansas A. E. Touzalin, land commissioner for the Santa Fe, became agent of the [[Burlington Railroad|Burlington and Quincy Railroad]]. In this capacity he made considerable effort to divert to [[Nebraska (USA)|Nebraska]] the immigrants which he had solicited for Kansas, since the Burlington ran through Nebraska. The Santa Fe secured [[Schmidt, C. B. (Carl Bernhard) (1843-1921?)|C. B. Schmidt]] as agent, who immediately contacted the Mennonites. | ||

| − | Meanwhile the movement from Russia continued. The large [[Alexanderwohl (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Alexanderwohl]] group arrived in New York aboard the <em>Cimbria </em>on 27 August 1874 and the <em>Teutonia </em>on 3 September 1874. It was met by [[Goerz, David (1849-1914)|David Goerz]], [[Ewert, Wilhelm (1829-1887)|Wilhelm Ewert]], and [[Schmidt, C. B. (Carl Bernhard) (1843-1921?)|C. B. Schmidt]] of the Santa Fe, all boosters for Kansas. The <em>Teutonia </em>group with [[Gaeddert, Dietrich (1837-1900)|Dietrich Gaeddert]] and [[Balzer, Peter (1847- | + | Meanwhile the movement from Russia continued. The large [[Alexanderwohl (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Alexanderwohl]] group arrived in New York aboard the <em>Cimbria </em>on 27 August 1874 and the <em>Teutonia </em>on 3 September 1874. It was met by [[Goerz, David (1849-1914)|David Goerz]], [[Ewert, Wilhelm (1829-1887)|Wilhelm Ewert]], and [[Schmidt, C. B. (Carl Bernhard) (1843-1921?)|C. B. Schmidt]] of the Santa Fe, all boosters for Kansas. The <em>Teutonia </em>group with [[Gaeddert, Dietrich (1837-1900)|Dietrich Gaeddert]] and [[Balzer, Peter (1847-1907)|Peter Balzer]] as leaders followed them to Kansas, while [[Buller, Jacob (1827-1901)|Jacob Buller]] and his group proceeded to Nebraska. Jacob Buller had refused to see Kansas as a delegate. Now he and his group soon went from Lincoln, NE, to Kansas, where they bought land in Marion and McPherson counties north of [[Newton (Kansas, USA)|Newton]]. This became the large Alexanderwohl settlement and church. The immigrants settled in villages similar to those they had left behind in Russia. The settlers who had come on the <em>Teutonia </em>under the leadership of Dietrich Gaeddert chose to settle 20 miles west of the Alexanderwohl settlement, purchasing about 35,000 acres of railroad land in the adjoining corners of Reno, McPherson, and Harvey counties. This settlement and church became known as [[Hoffnungsau Mennonite Church (Inman, Kansas, USA)|Hoffnungsau]]. The town of [[Buhler (Kansas, USA)|Buhler]] was founded in the heart of the settlement. |

Another group of some 109 families from Russian Poland arrived in Topeka about the same time. During the middle of the winter of 1874-1875, 265 more families followed. These were Swiss Volhynian Mennonites under the leadership of Jacob Stucky, one of the delegates, who settled along Turkey Creek in McPherson County in the vicinity of the present [[Moundridge (Kansas, USA)|Moundridge]]. They organized the Hoffnungsfeld congregation, the mother church of the [[Eden Mennonite Church (Moundridge, Kansas, USA)|Eden]] and other congregations. | Another group of some 109 families from Russian Poland arrived in Topeka about the same time. During the middle of the winter of 1874-1875, 265 more families followed. These were Swiss Volhynian Mennonites under the leadership of Jacob Stucky, one of the delegates, who settled along Turkey Creek in McPherson County in the vicinity of the present [[Moundridge (Kansas, USA)|Moundridge]]. They organized the Hoffnungsfeld congregation, the mother church of the [[Eden Mennonite Church (Moundridge, Kansas, USA)|Eden]] and other congregations. | ||

Latest revision as of 15:12, 9 January 2021

Introduction

Kansas is a Midwestern state located in the central region of the United States. It has a total area of 82,277 square miles (213,096 km²), and had an estimated population of 2,802,134 in 2008. In 2005, 90.87% of the population were White and 6.60% were African American. Kansas was organized as a territory in 1854 and admitted to the Union in 1861.

1957 Article

Introduction

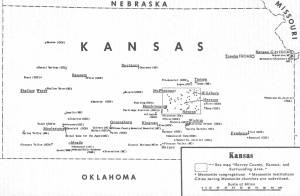

Kansas had a larger Mennonite population than any other state west of the Mississippi, most of whom came to America during the great Mennonite migration of the 1870s from Russia, Poland, and Prussia. The first Mennonites, however, to settle in Kansas came from the eastern states at an earlier date. M. W. Keim and his friends from Pennsylvania in 1869-1870 purchased from Case and Billings 5,000 acres near Marion Center. Attracted by the Homestead Act of 1862, Daniel, Christian, and Margaret Kilmer of Elkhart County, Indiana, settled in the southeastern part of McPherson County in 1871. This became the nucleus of the Spring Valley Mennonite Church (Mennonite Church), located on the western end of the "twenty-three mile furrow," which connected the scattered farms of the Pennsylvania-German Mennonites of this area. The east edge of the twenty-three mile furrow bordered on the Brunk farm and cemetery located on Highway 50 between Hillsboro and Marion. Here R. J. Heatwole and Henry G. Brunk located, coming from Virginia. Soon others followed from Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Missouri. The beginnings of this settlement preceded the great Mennonite migration to the prairie states and provinces from Russia by two years. Later Pennsylvania Mennonites (MC) established the following congregations: Catlin in Marion County in 1877, West Liberty in McPherson County in 1883, Pennsylvania in Harvey County in 1885, and Pleasant Valley in Harper County in 1897. The Amish of Yoder and Partridge in Reno County near Hutchinson came to Kansas starting in 1883, and an Amish Mennonite congregation was established at Crystal Springs in Harper County in 1904.

The Beginning of the Settlements of Mennonites from Russia, Poland, and Prussia

When the Mennonites settled in Russia in 1789 and the following years they were given written guarantees by the Czars that they could settle in solid communities, conduct their own schools, and have their own administration and also that they would be exempted from any form of military service. When rumors regarding a general conscription law came into circulation among the Mennonites in Russia around 1870 they were alarmed. Soon for some individuals of deep-rooted convictions, America appeared on the horizon. Among them was Cornelius Jansen. He was in touch with Russian and foreign authorities at Berdyansk, from whom he received information regarding Canada and America. Bernhard Warkentin and three friends came to the United States in 1872, making their headquarters at Summerfield, Illinois. Railroad agents tried to interest Warkentin in various settlement possibilities. Faithfully he reported all his experiences and findings to David Goerz of Berdyansk, who circularized the information among the Mennonites of the Molotschna settlement.

The first settlement by Mennonites from Russia in Kansas took place in 1873 when Peter and Jacob Funk bought land from the Santa Fe Railroad near the present site of Marion for $2.50 per acre. Christian Krehbiel, who was present at the time of the purchase, reports: "With this land purchase the die was cast for Kansas" (From the Steppes, 31). This was the beginning of the Brudertal Mennonite Church.

Meanwhile the Summerfield Mennonites also became interested in the land of the prairies. As a result of investigation trips they chose land near Halstead, KS. For $2.00—$15.00 the Santa Fe reserved for the Summerfield Mennonites land in townships 21, 22, 23, and 24, in McPherson and Harvey counties. Warkentin built a mill on the Arkansas River near Halstead. The first Summerfield Mennonites moved to Kansas in the spring of 1875, where the Halstead Mennonite Church was organized 28 March 1875.

Although the official delegates did not favor Kansas, and even Cornelius Jansen, who initiated the immigration to America, chose Nebraska, Kansas became the preferred state by most of the immigrants, in spite of the fact that Warkentin was not considered a delegate and was not specifically consulted by the delegation. One reason why some Mennonites preferred Canada above any of the prairie states was the fact that they were offered large compact areas such as the East Reserve and the West Reserve on the Red River, on which they could live just as they had in Russia, with their own schools and self-government. This none of the states could offer. After debating this question, the U.S. Congress felt that Mennonites would have to be satisfied with settling on alternate sections of land offered by the railroads. Regarding nonresistance the Canadian promises were also more specific than those of the United States.

While Congress was still debating the petitions the movement of the Mennonites from Russia, Poland, and Prussia to the United States set in. Wilhelm Ewert, the Prussian delegate, arrived in Peabody 16 May 1874 accompanied by a number of Prussian Mennonites. He joined the Funk brothers of Brudertal near Marion Center. Elder Jacob A. Wiebe and Johann Harder leading the Krimmer Mennonite Brethren, crossing the Atlantic with their group on the City of Brooklyn, arrived in New York on 15 July 1874. They settled on 12 sections of land in Marion County, establishing Gnadenau village and the Gnadenau Krimmer Mennonite Brethren Church.

In the midst of the Mennonite migration from Russia to Kansas A. E. Touzalin, land commissioner for the Santa Fe, became agent of the Burlington and Quincy Railroad. In this capacity he made considerable effort to divert to Nebraska the immigrants which he had solicited for Kansas, since the Burlington ran through Nebraska. The Santa Fe secured C. B. Schmidt as agent, who immediately contacted the Mennonites.

Meanwhile the movement from Russia continued. The large Alexanderwohl group arrived in New York aboard the Cimbria on 27 August 1874 and the Teutonia on 3 September 1874. It was met by David Goerz, Wilhelm Ewert, and C. B. Schmidt of the Santa Fe, all boosters for Kansas. The Teutonia group with Dietrich Gaeddert and Peter Balzer as leaders followed them to Kansas, while Jacob Buller and his group proceeded to Nebraska. Jacob Buller had refused to see Kansas as a delegate. Now he and his group soon went from Lincoln, NE, to Kansas, where they bought land in Marion and McPherson counties north of Newton. This became the large Alexanderwohl settlement and church. The immigrants settled in villages similar to those they had left behind in Russia. The settlers who had come on the Teutonia under the leadership of Dietrich Gaeddert chose to settle 20 miles west of the Alexanderwohl settlement, purchasing about 35,000 acres of railroad land in the adjoining corners of Reno, McPherson, and Harvey counties. This settlement and church became known as Hoffnungsau. The town of Buhler was founded in the heart of the settlement.

Another group of some 109 families from Russian Poland arrived in Topeka about the same time. During the middle of the winter of 1874-1875, 265 more families followed. These were Swiss Volhynian Mennonites under the leadership of Jacob Stucky, one of the delegates, who settled along Turkey Creek in McPherson County in the vicinity of the present Moundridge. They organized the Hoffnungsfeld congregation, the mother church of the Eden and other congregations.

The "Polish" Mennonites, led by Tobias Unruh, a delegate from Ostrog, Poland, left Antwerp late in November on three ships, Nederland, Vaderland, and Abbotsford. The group consisted of 265 families. The poorest 50 families remained in Pennsylvania for the winter while the others continued their trip to Kansas. The Mennonite Board of Guardians gave them aid and distributed them for the winter in the vicinity of Newton, Florence, and Great Bend. Most of them were settled on small farms in the spring, in the vicinity of Canton, later joining the Church of God in Christ, Mennonites, founded by John Holdeman. The Emmanuel Church and the Pawnee Rock Bergtal Mennonite Church also belong to this group. Later others moved to Oklahoma. Still others never came to Kansas but settled in Dakota. Only some 1,400 persons came to Kansas during 1875, the migration to Manitoba being much greater during this year.

C. Henry Smith reports that 1,275 families arrived in the United States and Canada during 1874. Of these, 600 families came to Kansas. In addition to these, 150 families temporarily remained in the east, some in Pennsylvania, some in Ontario. Thus about half of the total number of immigrants of 1874 came to Kansas. The next largest group went to Manitoba, after which followed the group to the Dakotas. The passengers used the Inman, Allen, Red Star, Hamburg-America, and Adler lines. Some arrived in New York and others in Philadelphia. C. B. Schmidt, the most enthusiastic agent, who secured some letters of introduction from Mennonites who had arrived in Kansas, left New York on 1 February 1875 and went to Russia to win more immigrants for Kansas. Yet 1874 remained the peak year for Mennonite immigration to Kansas. According to Shipley, the total number of Mennonites immigrating to North America in 1874 was 6,402, of whom it was estimated that about 5,300 came to the United States, with nearly 3,000 coming to Kansas (p. 87).

The Prussian Mennonites, founding the Emmaus Mennonite Church, the First Mennonite Church of Newton, and the Zion Mennonite Church at Elbing, began to come to Kansas in 1876 and the following years. Among them was Leonhard Sudermann of Berdyansk, who had originally not been impressed by Kansas. Only smaller numbers reached Kansas after this. The steamer Strassburg, arriving in New York on 1 July 1878 carried 35 families headed for Kansas. The steamer Switzerland, arriving in June 1879, brought 42 additional families to Kansas. Of the Swiss Galician Mennonites 22 families came to Kansas, settling near Arlington and Hanston. By 1880 the immigration had dwindled down to a few families per year. Again in 1884 some Central Asian Mennonite families reached Newton. Abraham Schellenburg arrived in Kansas in 1879 with some Mennonite Brethren, settling at Buhler and Hillsboro.

The first Brethren in Christ reached Abilene, Kansas in 1879, coming from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. This denomination also developed settlements and congregations in Brown and Dickinson counties and elsewhere.

Of the approximately 18,000 Mennonites that came to North America from Russia in 1873-1884, about 10,000 came to the United States, of whom possibly 5,000 settled in Kansas. No one has yet attempted to establish the exact figures. According to T. R. Schellenburg, the census schedule of 1880 revealed that 7,000 persons (German-speaking) were settled in Marion, Reno, McPherson, and Harvey counties, of whom 74 per cent were from Russia, 17 per cent from Poland, and 9 per cent from Germany. Most of them were Mennonites.

Kansas was a competitor to Manitoba. The Old Colony, Bergthal, and other conservative groups were won for Manitoba because the Canadian government promised them what they asked for; i.e., land for compact settlements, self government, and their own schools. Kansas received a large portion of the Molotschna, the Prussian, the Swiss Volhynian, the Swiss Galician, and the Polish Mennonites. No Old Colony Mennonites from Chortitza, with the exception of those few who had joined the Mennonite Brethren, came to Kansas.

There were a number of factors influencing the decision of so many Mennonites from Russia to settle in Kansas. The Kansas railroads were great boosters and competitors. Christian Krehbiel and Bernhard Warkentin, who advised and counseled many of the Mennonite leaders, were Kansas boosters from the beginning. Through Warkentin, David Görz, who was still in Russia, advertised and spread the good news about Kansas. He continued this promotion in his paper Zur Heimath, which he edited and published in Halstead, and through his booklet Die Mennoniten-Niederlassung auf den Ländereien der Atchison, Topeka, und Santa Fe Eisenbahn. Most important, however, was very likely the fact that Kansas was located geographically very much the same as the Ukraine whence the Mennonites came. The weather, the crops, and the general conditions were very similar to those of the Molotschna settlement. Winter wheat and even watermelons could be expected to grow here just as in Russia. The water level could easily be reached. Many feared the severe winters of Manitoba, Minnesota, and Dakota.

The following sections apply primarily to the Mennonites who came from Russia:

Economic Life

The economic status and background of the Kansas Mennonite farmers differed greatly. Some had been successful and prosperous farmers, and brought a considerable amount of money; others were poor and had to borrow money. They needed the aid of the Mennonite Board of Guardians and others. Generally speaking, the Mennonites of Prussia and the Molotschna were prosperous and advanced in culture. The economic status and the educational level of the Mennonites coming from Poland was considerably lower. All of them seemed to intend to continue their accustomed way of life. The Alexanderwohl immigrants settled in villages north of Newton. Noble L. Prentis has given us a vivid portrayal of Mennonite life in that community in 1874-1877. In "The Mennonites in Kansas," "The Mennonites at Home," and "A Day with the Mennonites" (see From the Steppes) he describes their life at home, their dress, their food, how they farmed, and their qualities as farmers, such as patience, endurance, skill, and success in spite of pioneer difficulties and grasshopper plagues.

Against the advice of Warkentin the settlers brought with them all kinds of furniture, tools, and implements, even wagons and plows. If they had forgotten anything they wrote to relatives to bring it along; e.g., gooseberry sprouts or tulip bulbs. They transformed the prairie by erecting their homes on their quarter sections or in villages surrounded by rows of shade trees, mulberry trees, and fields of waving grain. Mulberry hedges were planted to provide food for the silkworms, an industry which they brought from the Ukraine and intended to continue on the Kansas prairies. A silk mill was established in Peabody, KS, but it did not prosper. Some of the typical furniture gradually disappeared. Threshing stones and other implements used in the early days can be seen today in the Kauffman Museum of Bethel College. Mulberry hedges, Russian olive trees, thistles, and bindweeds can still be found in Kansas. Even Russian watermelons have responded to the "survival of the fittest."

The most important economic contribution of the Mennonites was the introduction of hard winter wheat. In 1874 the Mennonites from Russia sowed the first winter wheat seed which they had brought with them. After experimenting with different varieties they found that the hard red Turkey winter wheat was best suited to the soil and the climatic conditions of Kansas. It gradually spread into the neighboring non-Mennonite counties of Kansas. Warkentin, whose father had been a miller in the Ukraine, and who had established a mill in Halstead, ordered a large shipment from the Crimea in 1885-1886 for distribution among the farmers of Kansas, and established the Newton Milling and Elevator Co., using steel rollers instead of stone burrs to grind the hard wheat. Warkentin also continued to experiment with different varieties of wheat on his own experiment station in Halstead. In 1900 the Kansas State Millers Association and the Kansas Grain Dealers Association asked Warkentin to import a large shipment of seed wheat from the Ukraine. As a result 15,000 bushels were imported and distributed to farmers the next year. In 1896 Mark A. Carleton of the United States Department of Agriculture came to Warkentin to inquire about his experiments with wheat. Carleton went to the Ukraine in 1898 to study the Turkey wheat in its native country. Warkentin located a plot for him near Halstead where he could experiment with some 300 varieties of wheat from Russia. Numerous varieties of wheat have been developed since. Kansas still raises the wheat the Mennonites introduced 80 years ago, although other newer varieties have now taken precedence over the Turkey variety. The Mennonites of Kansas were pioneers in transforming the prairies into wheat fields and thus helped make Kansas a bread basket for the world.

| Towns in Kansas Showing Mennonite Population and businesses, 1924 | |||

| Name | Established | Population, 1924 | % Controlled by Mennonites |

| Buhler | 1887 | 600 | 75 |

| Goessel | 1893 | 100 | 100 |

| Halstead | 1873 | 1,200 | 13 |

| Hesston | 1886 | 600 | 50 |

| Hillsboro | 1879 | 1,574 | 85 |

| Inman | 1886 | 432 | 75 |

| Lehigh | 1879 | 395 | 30 |

| Moundridge | 1886 | 800 | 60 |

| Newton | 1872 | 10,000 | 5* |

| *90% of flour milling; 50% of the banking | |||

The great handicap in the economic life of the Mennonites of Kansas is the fact that the prairie states from time to time experience a cycle of drought. Farming has undergone many changes, but basically it remains the same. Grain and dairy farming are found everywhere.

Unlike the Mennonites of Russia, the Kansas Mennonites, with the exception of the milling industry in which Warkentin and Rudolph Goerz were prominent, never played a very significant role in the production of machinery or in industry. In the 1950s the activities of the Mennonites along this line were confined mostly to feed mills and grain elevators, some of which were co-operative enterprises. The Buller Manufacturing Company of Hillsboro and the Hesston Manufacturing Company produced some agricultural machinery. In Newton the Mennonites were leaders in the banking business. Most of the Mennonite communities had banks and businesses operated by Mennonites. The accompanying table of Mennonite businesses for 1924 was probably still true in the 1950s with the exception of the milling industry in Newton, which was became almost entirely in non-Mennonite hands. In other cases there might be an increase in Mennonite business in these towns.

In addition to these towns the following have a predominately or strong Mennonite population: North Newton, Elbing, Whitewater, Canton, Walton, Marion, McPherson, Peabody, and Yoder. The large cities, like Wichita, Hutchinson, Topeka, Lawrence, and Kansas City, have a constantly increasing Mennonite population; some of these Mennonites have established congregations.

Cultural Life

One of the reasons why the Mennonites came to America was their insistence on maintaining their religious and cultural life as they had inherited it. To promote this, schools and churches were immediately erected everywhere. In both of them the use of the Bible and the German language prevailed for many years. Gradually the parochial schools were replaced by public schools, but some of them continued, supplementing the education of the public schools with instruction in Bible and the German language. Some of these schools, like the Emmatal school, became secondary schools patterned after the traditional Russian Mennonite Zentralschule. The Halstead Seminary, the forerunner of Bethel College, founded in 1882, was the first step toward collegiate education. Preparatory schools were established in all larger Mennonite communities such as Hillsboro, Goessel, and Moundridge. A Kansas Conference was organized in the interest of education. The Teachers' Association (Lehrerverein) played a very significant role in the promotion of education. Bethel College was established at its present location in 1887 as the successor to the Halstead Seminary, serving primarily the General Conference Mennonite Church constituency of the prairie states and provinces. Tabor College at Hillsboro, founded by the Mennonite Brethren, was established in 1908. Hesston College of the Mennonite Church (MC) was established in 1909 to serve the congregations of that group west of the Mississippi. Each of these three schools, located within a radius of 30 miles, maintained an academy which offered high-school subjects, and Hesston College still did in the 1950s. The curriculum of the colleges has grown and changed in accordance with the trends of education and the demands of the constituencies.

In all the Mennonite communities nearly all the young people attended high schools by the 1950s. In some of them religious instruction was given. Zoar Academy, sponsored by the Krimmer Mennonite Brethren, was discontinued. New secondary parochial schools were established in the Berean Academy at Elbing and the Central Kansas Bible Academy at Hutchinson.

The pattern of the cultural life of the Mennonites of Kansas has changed considerably. Not only have the walls which separated the various ethnic and cultural groups, such as the Swiss Volhynian, Low German, Prussian, and Polish background Mennonites, been torn down, but also the walls between all groups and their environment. The former practice of nonconformity has either received an entirely new interpretation or has been nearly forgotten. The barrier of language and customs has been almost completely removed, with the exception of some of the more conservative groups. As a rule, Mennonites fulfill their obligations as citizens in voting. Some of them even choose the legal profession as a vocation. It was formerly said that Mennonites stayed out of court and that there are no divorces in Mennonite communities. By mid-20th century this was no longer completely true.

Religious Life

Out of the Kansas Conference came the Western District Conference of the General Conference Mennonite Church. Of the 66 congregations of the Western District in 1955, 53 were located in Kansas, which was by far the largest number of General Conference congregations in any of the states or provinces. The membership was 11,118 in 1955 and the total population including children, 15,552. The Mennonite Brethren had 10 congregations in Kansas (2,000 members, 1951); the Krimmer Mennonite Brethren 3 (449 members, 1955); the Church of God in Christ, Mennonite, 14 (1,917 members, 1954); the Evangelical Mennonite Brethren 2 (297 members, 1955); Mennonite Church (MC) 13 (1,575 members, 1954); the Brethren in Christ 5 (240 members, 1955); the Evangelical Mennonite Church 1 (143 members, 1955); the Old Order Amish had 6 districts (386 members, 1954); the Conservative Mennonites 1 (113 members, 1954). Regarding the more conservative groups it can be said that through the contact with other Mennonite groups in Civilian Public Service and in relief projects, their spiritual life and their forms of worship was revitalized and as a rule they developed an active program of missionary and evangelistic outreach. Interest in education was growing continually. Kansas, with its three Mennonite colleges and many secondary schools, was not only the center for the Mennonites of the prairie states as far as education was concerned, but also a center for Conference organizations and publications. The General Conference headquarters were located in Newton, where the various boards of the Conference did their business. The Conference maintained a bookstore in Newton, and together with Bethel College, a Mennonite Press in North Newton. In North Newton there was also a clothing center of the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) for the prairie states. At Newton was the Prairie View Hospital, a mental hospital operated by the MCC.

Hillsboro, located some 28 miles (45 km) north of Newton in Marion County, has become the national headquarters for the Mennonite Brethren. In 1955 it was the location of the largest Mennonite Brethren congregation east of California, the Mission Board of the Mennonite Brethren, the Mennonite Brethren Publishing House and bookstore, and Tabor College. Hesston and Hesston College, six miles northwest of Newton, have become a center for the Mennonite Church (MC) in Kansas. All three college campuses were being used extensively by their constituencies for conferences, and religious and cultural programs sponsored by the respective colleges. Bethel Deaconess Home and Hospital at Newton, Bethesda Hospital at Goessel, and Salem Hospital at Hillsboro, as well as the Mercy Hospital at Moundridge, and a number of homes for the aged were Mennonite-sponsored institutions. The Hertzler Clinic of Halstead was originally also sponsored and supported by the Mennonites. Midland Mutual Fire Insurance, the oldest fire insurance of Kansas, was originally a Mennonite organization, founded by David Goerz.

The total Mennonite church membership of Kansas was 18,294 in 1955. This would make a total Mennonite population (including children) of about 30,000. Many Kansas Mennonites have migrated to Oklahoma and the Pacific Coast to establish settlements of various Mennonite branches in these areas. -- Cornelius Krahn

1990 Update

The Mennonite population and institutions of Kansas have exhibited many continuities over the past 30 years. The Mennonite church membership in Kansas was 21,417 in 1985, compared with a total of 18,294 in 1955. Mennonites constituted roughly one percent of the population of Kansas.

Kansas had 109 Mennonite congregations in 1985 (including 5 Old Order Amish congregations or "districts") representing 10 Mennonite groups, compared with 108 congregations and 9 groups in 1955. The Western District. Conference was the largest district of the General Conference Mennonite Church with 70 congregations and 14,000 members. Of this total, 47 congregations with 11,776 members were in Kansas (53 — 11,118). (The number of congregations and membership from 1954 or 1955 are given in parentheses). The Mennonite Brethren had 16 congregations in Kansas with 3,600 members (13 — 2,449, including 3 Krimmer Mennonite Brethren congregations); Church of God in Christ, Mennonite 19 and 3,145 (14 — 1,917); Evangelical Mennonite Brethren, 1 and 133 (2 — 297; Evangelical Mennonite Church, 1 and 222 (1 — 143); Conservative Mennonites, 3 and 188 (1 — 113); Brethren in Christ, 4 and 280 (5 — 240); Mennonite Church, 18 and 2,358 (13 — 1,575); Beachy Amish, 2 and 298 (no listing); and Old Order Amish, 5 districts and about 400 members (6 districts — 386).

These statistics do not reveal several significant changes. Nearly one-third of the Mennonite congregations existing in 1955 were extinct in 1985, and an almost equal number of new congregations were established during those years. The rural Mennonite communities generally experienced declining population with many of the smaller congregations, especially those in western Kansas, closing or moving to nearby urban centers. The congregations established during these 30 years tended to be in urban centers such as Kansas City, Topeka, Wichita, Manhattan, Lawrence, and Newton. Included in this number were several *"house" churches and university fellowships with different patterns of organization, leadership and commitment. Also of special interest are several congregations affiliated with two or more of the Mennonite groups. Six congregations belonged to both the South Central Conference (MC) and the Western District Conference (GCM). One congregation, the Manhattan Mennonite Fellowship, maintained this dual affiliation and also a third membership in the Southern District (MB). The dual-conference congregations represented growing cooperation on various projects and levels between the General Conference Mennonite Church and the Mennonite Church.

Central Kansas remained a major Mennonite educational and organizational center. Bethel, Tabor and Hesston Colleges not only educated the youth of the General Conference, Mennonite Brethren, and Mennonite Church respectively, but also provided a vast array of cultural programs and continuing education activities for their constituencies. The General Conference headquarters in Newton expanded several times following the 1950s, and the Western District of the General Conference now maintained it offices in North Newton. The Mennonite Press (also Faith and Life Press) operated by Bethel College and the General Conference, moved from North Newton to facilities at the Newton airport. The Mennonite Library and Archives, sponsored by Bethel College and the General Conference, moved into expanded facilities within the Mantz Library (dedicated 5 October 1986) on the Bethel College campus. The Center for Mennonite Brethren Studies at Tabor College, organized in 1974, served as the archival center for Mennonite Brethren congregations in the United States, excluding the Pacific District. Mennonite Brethren Bible and seminary education shifted from Hillsboro to Fresno, California and in 1979 Tabor College became an area college operated by a Senate with representatives from the Southern, Central, North Carolina, and Latin American (South Texas) Mennonite Brethren districts. The Mennonite Brethren Publishing House in Hillsboro was sold in 1982, but The Christian Leader office remained in Hillsboro. The national offices of the Mennonite Brethren Board of Missions were in Hillsboro and Winnipeg. Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) operated a regional office with a clothing distribution center in North Newton.

The ethnic and religious distinctiveness of the Kansas Mennonites continued to erode after the 1950s. Only a few conservative groups maintained their own schools, plain dress, or German language. The manifestations of nonconformity nearly all disappeared. Kansas Mennonites have entered the various modern professions and experienced virtually every modern social problem. While many Mennonites were distinguished from the general population by their strong social consciousness and service ethic, the Mennonite emphasis on nonresistance dwindled within most groups. A variety of celebrations promoted Mennonite culture and ethnic food.

Nevertheless, Kansas Mennonites were leaders in promoting peace education and social involvement. A vast array of hospitals, retirement homes, and other institutions in central Kansas operated with direct or indirect ties to Mennonite congregations or conferences. Mennonites ministered to inmates in prisons and provided assistance to those afflicted by natural disasters through Mennonite Disaster Service. Prairie View, a mental hospital founded by MCC east of Newton, continues its leadership in mental health care. A few Mennonite institutions closed, such as Bethesda Hospital in Goessel, creating a deep sense of loss within communities. New institutions, e.g., the Kidron retirement community in North Newton, continued the impact of Mennonite institutions on the quality of life in central Kansas. -- David A. Haury

| Anabaptist/Mennonite Groups in Kansas, 2000 | ||

| Denomination | Congregations | Adherents |

| Amish, Other | 2 | 134 |

| Beachy Amish Mennonite | 3 | 392 |

| Brethren in Christ Church | 4 | 525 |

| Church of God in Christ, Mennonite | 22 | 4,587 |

| Church of the Brethren | 30 | 3,690 |

| Conservative Mennonite Conference | 2 | 284 |

| Evangelical Mennonite Church | 3 | 469 |

| Mennonite Brethren | 17 | 4,691 |

| Mennonite Church | 53 | 14,297 |

| Mennonite, Other | 9 | 1,609 |

| Old Order Amish | 6 | 406 |

| Total | 151 | 31,084 |

See also Acculturation; Politics; Publishing.

Bibliography

Albrecht, Abraham. "Mennonite Settlements in Kansas." MA thesis, Kansas, 1924.

ARDA: The Association of Religion Data Archives. "State Membership Report - Kansas: Denominational Groups, 2000." http://www.thearda.com/mapsReports/reports/state/20_2000.asp (accessed 18 February 2009).

Bradley, G. D. The Story of the Santa Fe. Boston, 1920.

Correll, Ernst. "The Congressional Debate on the Mennonite Immigration from Russia, 1873-74." Mennonite Quarterly Review 20 (February 1946): 174-188.

Dyck, Cornelius J. "Kansas Promotional Activities with Particular Reference to Mennonites." M.A. thesis, Municipal University of Wichita, 1955.

Dyck, Edward A. Riesen and Dyck: Hardware and Implements. Hutchinson: Edward A. Dyck, 1984.

Engbrecht, Dennis D. "The Americanization of a Rural Immigrant Church: The General Conference Mennonites in Central Kansas, 1874-1939." PhD dissertation, University of Nebraska, 1985.

Erb, Paul. South Central Frontiers: A History of the South Central Mennonite Conference. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1974.

Gaeddert, G. Raymond. The Birth of Kansas. Lawrence, KS, 1940.

Goering, Jacob D. and Robert Williams. "Generational Drift on Four Variables Among the Swiss Volhynian Mennonites in Kansas." Mennonite Quarterly Review 50 (1976): 290-297.

Harder, Leland. A Joint Study of Four Hillsboro-Lehigh Area Churches in Kansas. Typescript, 1964.

Harms, Orlando. Pioneer Publisher: The Life and Times of F. Harms. Winnipeg, MB: Kindred Press, 1984.

Haury, David A. "Bernhard Warkentin: a Mennonite Benefactor." Mennonite Quarterly Review 49 (1975): 179-202.

Haury, David A. A People of the City: A History of the Lorraine Avenue Mennonite Church, 1932-82. Wichita: Lorraine Avenue Mennonite Church, 1982.

Haury, David A. Prairie People: A History of the Western District Conference. Newton, KS, Faith and Life, 1981.

Hertzler, Arthur E. "What Kansas Mennonites Have Produced." Kansas Magazine (1939): 87.

Herald of Truth (Elkhart, IN, 1873 ff).

Herold der Wahrheit (Elkhart, IN, 1871 ff.)

Hiebert, Clarence, ed. Brothers in Deed to Brothers in Need: A Scrapbook about Mennonite Immigrants from Russia 1870-1885. Newton, KS, Faith and Life, 1974.

A History of the First Mennonite Church: Pretty Prairie, Kansas. Pretty Prairie: Prairie Publications, 1983.

Holsinger, Justus G. Upon this Rock: Remembering Together the Seventy-five Year Story of Hesston Mennonite Church. Hesston: Hesston Mennonite Church, 1984.

Janzen, C. C. "A Social Study of the Mennonite Settlement in the Counties of Marion, McPherson, Harvey, Reno, and Butler, Kansas." PhD thesis, Chicago, 1926.

Juhnke, James C. A People of Two Kingdoms: The Political Acculturation of the Kansas Mennonites. Newton, KS, Faith and Life, 1975.

"Kansas Mennonite Settlements, Part II: Illustrations." Mennonite Life 25 (April 1970): 65-80.

Kaufman, Ed. G. "Social Problems and Opportunities of the Western District Conference Communities of the General Conference of Mennonites of North America." MA. thesis, Witmarsum Seminary, 1917.

Krahn, Cornelius. "A Centennial Chronology, Part One and Part Two." Mennonite Life 28 (May-June, 1973): 3-9, 40-45.

Krahn, Cornelius (editor). From the Steppes to the Prairies. Newton, KS, 1949.

Krahn, Cornelius. "Mennonite Centennial Publications." Mennonite Life 29 (May-June 1974): 47.

Krahn, Cornelius. "Some Letters of Bernwhard Warkentin Pertaining 'to the Migration of 1873-1875." Mennonite Quarterly Review 24 (July 1950): 248-263.

Krahn, Cornelius. "Views of the 1870s Migrations by Contemporaries." Mennonite Quarterly Review 48 (1974): 447-459.

Krehbiel, Christian. Prairie Pioneer: The Christian Krehbiel story. Newton, KS: 1961.

Leibbrandt, Georg. "The Emigration of the German Mennonites from Russia to the United States and Canada in 1873- 1880." Mennonite Quarterly Review 6 (October 1932): 205-226; 7 (January 1933): 5-41.

Malin, James C. Winter Wheat in the Golden Belt of Kansas. Lawrence, 1944.

McQuillan, David Aldan. "Adaptation of Three Immigrant Groups to Farming in Central Kansas, 1875-1925." PhD dissertation, University of Wisconsin, 1975.

Miller, Joseph S. Beyond the Mystic Border: the Pennsylvania Mennonite Congregation near Zimmeredale, Kansas. MA thesis, Villanova University, 1984.

Pantle, Alberta "Settlement of the Krimmer Mennonite Brethren at Gnadenau, Marion County." Kansas Historical Quarterly 13 (February 1945): 259-285.

Peace, Progress, Promise: A 75th Anniversary History of Tabor Mennonite Church. Newton: Tabor Mennonite Church, 1983.

"Pioneers, Wheat, and Faith. Centennial Photo Section." Mennonite Life 29 (May-June 1974): 24-29.

Preheim, Marion Keeney. The Story of Faith: Twenty-five Years, 1958-1983. Newton, KS: Faith Mennonite Church, 1983.

Ratzlaff, Abraham. Diary of the Reverend Abraham Ratzlaff. North Newton, KS: Bethel College, 1983.

Ratzlaff, Abraham. Memoirs of the Reverend Abraham Ratzlaff. North Newton, KS: Bethel College, 1983.

Reimer, Gustav E. and G. R. Gaeddert. Exiled by the Czar: Cornelius Jansen and the Great Mennonite Migration, 1874. Newton, KS, 1956.

Rogers, Laurine A. "Phylogenetic Identification of a Religious Isolate and the Measurement of Inbreeding." PhD dissertation, University of Kansas, 1984.

Schmidt, C. B. "Kansas Mennonite Settlements, 1877 Part I: Text." 25, Mennonite Life (April 1970): 51-58.

Schrag, Lester D. "Elementary and Secondary Education as Practiced by Kansas Mennonites." PhD dissertation, University of Wyoming, 1970.

Shipley, Helen B. The Migration of the Mennonites from Russia, 1873-1883, and Their Settlement in Kansas." MA thesis, Minnesota, 1954.

Smith, C. Henry. The Coming of the Russian Mennonites. Berne, IN, 1927.

Stucky, Gail Niles. A Guide to Congregational Records in the Western District Conference. North Newton, KS: Bethel College, 1983.

Stucky, Phillip P. Heritage and Memories of Phillip P. Stucky. Seattle: Phillip P. Stucky 1984.

Suderman, Frieda Pankratz Commitment and Reaffirmation: the First Mennonite Church, Hillsboro, Kansas. Hillsboro: First Mennonite Church, 1983.

Swiss-German Cultural and Historical Association. A Study Guide of the Swiss Mennonites Who Came to Kansas in 1874. Kansas: Swiss-German Cultural and Historical Association, 1974.

Waters, L. L. Steel Trails to Santa Fe. Lawrence, KS, 1950.

Wedel, P. P. Kurze Geschichte der aus Wolhynien, Russland, nach Kansas ausgewanderten Schweizer-Mennoniten. N.p., 1929.

Wiebe, David V. They Seek a Country: A Survey of Mennonite Migrations. Freeman: Pine Hill Press, 1974 edition.

Yoder, Gideon G. "The Oldest Living American Mennonite Congregations of Central Kansas." MA. thesis, Phillips University, 1948.

Zur Heimath. Halstead, 1876-81.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe; Schneider, 1913-1967:II: 458 f.

See also articles on Kansas in Mennonite Life

For additional congregational histories (to 1981), see Haury, Prairie People.

| Author(s) | Cornelius Krahn |

|---|---|

| David A. Haury | |

| Date Published | February 2009 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Krahn, Cornelius and David A. Haury. "Kansas (USA)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. February 2009. Web. 22 Nov 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Kansas_(USA)&oldid=169739.

APA style

Krahn, Cornelius and David A. Haury. (February 2009). Kansas (USA). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 22 November 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Kansas_(USA)&oldid=169739.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 3, pp. 143-148; vol. 5, pp. 479-480. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.