Difference between revisions of "Pennsylvania (USA)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m (Formatted headings.) |

m (Formatted images.) |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

The first settlers were a group of English Quakers who founded the city of Philadelphia in 1681. In the meantime the English Quakers had established several Quaker congregations in Holland and among the Mennonites along the German Rhine (e.g., [[Krefeld (Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)|Krefeld]], [[Kriegsheim (Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany)|Kriegsheim]] in the [[Palatinate (Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany)|Palatinate]]). To these, as well as to all the religious groups that were oppressed by their various governments along the Rhine, Penn issued a cordial invitation, offering them complete toleration - civil and religious - in his new colony. The first to respond to this call was a group of thirteen families from the region of Krefeld, former Mennonites, but by this time victims of Quaker missionary zeal. All of them but one family were now Quakers. The heads of these families were Dirck op den Graeff, Hermann op den Graeff, Abraham op den Graeff, Lenart Arets, Thones Konders, Reinert Tisen, Willem Stfepers, [[Lensen, Jan (17th century)|Jan Lensen]], [[Keurlis, Pieter (17th/18 centuries)|Peter Keurlis]], Jan Siemens, [[Bleikers, Johann (ca. 1655-1741)|Johannes Bleikers]], Abraham Tunis, and [[Luykens, Jan (d. 1744)|Jan Luykens]]. This group arrived at Philadelphia on 6 October 1683; and, proceeding some six miles north of the newly established Philadelphia, founded a new settlement that they called [[Germantown Mennonite Settlement (Pennsylvania, USA)|Germantown]] on land which they had purchased from Francis Daniel Pastorius, who had preceded them to America by a few months as agent for the Frankfort Land Company. | The first settlers were a group of English Quakers who founded the city of Philadelphia in 1681. In the meantime the English Quakers had established several Quaker congregations in Holland and among the Mennonites along the German Rhine (e.g., [[Krefeld (Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)|Krefeld]], [[Kriegsheim (Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany)|Kriegsheim]] in the [[Palatinate (Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany)|Palatinate]]). To these, as well as to all the religious groups that were oppressed by their various governments along the Rhine, Penn issued a cordial invitation, offering them complete toleration - civil and religious - in his new colony. The first to respond to this call was a group of thirteen families from the region of Krefeld, former Mennonites, but by this time victims of Quaker missionary zeal. All of them but one family were now Quakers. The heads of these families were Dirck op den Graeff, Hermann op den Graeff, Abraham op den Graeff, Lenart Arets, Thones Konders, Reinert Tisen, Willem Stfepers, [[Lensen, Jan (17th century)|Jan Lensen]], [[Keurlis, Pieter (17th/18 centuries)|Peter Keurlis]], Jan Siemens, [[Bleikers, Johann (ca. 1655-1741)|Johannes Bleikers]], Abraham Tunis, and [[Luykens, Jan (d. 1744)|Jan Luykens]]. This group arrived at Philadelphia on 6 October 1683; and, proceeding some six miles north of the newly established Philadelphia, founded a new settlement that they called [[Germantown Mennonite Settlement (Pennsylvania, USA)|Germantown]] on land which they had purchased from Francis Daniel Pastorius, who had preceded them to America by a few months as agent for the Frankfort Land Company. | ||

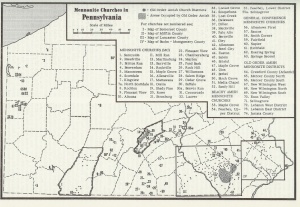

| − | [[File:ME4_137.jpg|300px|thumb| | + | [[File:ME4_137.jpg|300px|thumb|left|''Mennonite Churches in Pennsylvania, 1959.<br /> |

Source: Mennonite Encyclopedia, v. 4, p. 137'']] | Source: Mennonite Encyclopedia, v. 4, p. 137'']] | ||

Revision as of 06:33, 5 September 2013

Introduction

Pennsylvania, one of the original thirteen American colonies along the Atlantic coast, has an area of 46,055 square miles (119,283 km²) and a 2008 estimated population of 12,448,279.

Pennsylvania was founded by the English Quaker, William Penn, to whom the land had been granted by King Charles II in 1681. It was named Pennsylvania by the king himself, against the wishes of Penn, who as a Quaker was opposed to any name that might be interpreted as an attempt to glorify himself. The grant was of the proprietary type - that is, Penn as proprietor was granted complete ownership of the land, to dispose of it as he wished, with almost unlimited political power to govern the settlers with such political institutions as he thought best. It was Penn's purpose to establish here on the virgin soil of America a refuge for the English Quakers, who were being severely oppressed in their own country, and also other religious groups in Europe who were still being denied the usual civil and religious rights enjoyed by the established state churches. With this purpose in mind he granted the settlers a liberal frame of government and complete religious liberty.

Immigration

The first settlers were a group of English Quakers who founded the city of Philadelphia in 1681. In the meantime the English Quakers had established several Quaker congregations in Holland and among the Mennonites along the German Rhine (e.g., Krefeld, Kriegsheim in the Palatinate). To these, as well as to all the religious groups that were oppressed by their various governments along the Rhine, Penn issued a cordial invitation, offering them complete toleration - civil and religious - in his new colony. The first to respond to this call was a group of thirteen families from the region of Krefeld, former Mennonites, but by this time victims of Quaker missionary zeal. All of them but one family were now Quakers. The heads of these families were Dirck op den Graeff, Hermann op den Graeff, Abraham op den Graeff, Lenart Arets, Thones Konders, Reinert Tisen, Willem Stfepers, Jan Lensen, Peter Keurlis, Jan Siemens, Johannes Bleikers, Abraham Tunis, and Jan Luykens. This group arrived at Philadelphia on 6 October 1683; and, proceeding some six miles north of the newly established Philadelphia, founded a new settlement that they called Germantown on land which they had purchased from Francis Daniel Pastorius, who had preceded them to America by a few months as agent for the Frankfort Land Company.

One of these colonist families remained Mennonite; others soon followed from the Lower Rhine region, and later from Hamburg-Altona in Germany, so that a Mennonite congregation was formed by 1690 (or 1702). This was not only the first Mennonite church to be established in America, but the first German settlement of any sort in North America. Germantown is to the Germans of America what Jamestown is to the English. In 1702, a lot was set-aside for a Mennonite meetinghouse that was built in 1708 on the site of the present little stone building erected in 1770.

In 1702 Matthias van Bebber started a new Mennonite settlement along Skippack Creek, some 15 miles to the northwest in what is now Montgomery County, which has since grown to numerous congregations in what came to be known as the Franconia district, extending 30 miles north and an equal distance west, covering most of the Montgomery County and Bucks County area and spilling over into the counties of Chester, Berks, Lehigh, and Northampton. In 1707 a few Mennonites came from the Palatinate to Germantown.

Beginning with 1710 there was a continuous migration of Mennonites from Switzerland and the German Palatinate, which continued more or less regularly throughout the 18th century up to the time of the French and Indian War (1756-63). Part of these filled up the Franconia settlement. The rest made their way some 60 miles west of Philadelphia, along the Pequea and Conestoga valleys, in what is now Lancaster County, which is today almost solidly Mennonite in most of its rural area. The very first settlers here in 1710 came directly from Switzerland, the rest mostly from the Palatinate. There was little immigration from Europe to Pennsylvania during the wars from 1756 to 1815; after that, Mennonites as well as others who sought greater freedom in America chose the cheaper lands farther west beyond the Allegheny Mountains, so that Mennonite immigration to Pennsylvania was to all intents ended by 1756. The total Mennonite immigration may have reached 3,000 persons. The Lancaster County settlement spilled over into York, Cumberland, Dauphin, and Lebanon counties.

Beginning with 1736 the Amish also followed the Mennonites to the "Paradise of Pennsylvania," but located their first settlement somewhat northeast of the land occupied by the Mennonites in Lancaster, farther out on the frontier, along the Blue Ridge Mountains in what is now northern Berks County. During the Indian Wars that followed in 1754 they were driven south, and the first settlement was abandoned for safer areas in Lancaster and Chester counties on the eastern Lancaster fringe from Morgantown to Atglen. The Amish immigration did not total more than 400 persons.

Numerous religious nonresistant German groups and mystics, Dunkards, Schwenckfelders, Moravians, and other smaller German sects soon found their way to the land of freedom from the oppression of the Old World. The smaller nonresistant groups, including Mennonites and Amish, however, formed only a small part of the German migration to Pennsylvania during this period. There was a large influx from South Germany of members of the Protestant state churches - Reformed and Lutheran. These were followed before the middle of the 18th century by the Scottish-Irish, who, finding that the best lands of southeastern Pennsylvania had been taken over by the Germans and the English Quakers, were forced to seek homes farther out on the frontier, along the foothills of the Alleghenies. So by the time of the Revolutionary War (1776), Pennsylvania was settled by the English Quakers, Germans of all religious groups, and the Scottish-Irish (mostly Presbyterians), all enjoying perfect religious liberty, living side by side in peace and contentment. The Mennonites, although they were the first German settlers in the province, formed only a small part of the entire German population by the close of the century. It is estimated that by 1776 there were about 100,000 Germans in Pennsylvania, constituting perhaps about one third of the entire population. Of this number the Mennonites and Amish were not more than 10 per cent.

Most of the Mennonites who immigrated during this time were poor, many of them without sufficient money to pay for their passage. Their Dutch brethren organized the Commission for Foreign Needs, which greatly aided the emigration movement. Some, too, were able to bargain with ship captains for free passage across, in return for which the captain might sell their services (for a number of years) at auction upon their arrival at Philadelphia. These were called "redemptioners." A number of Mennonites came under this head, though the number among them was not as great as among other groups.

The poor economic conditions prevailing throughout the 18th century in the Palatinate, from which came nearly all of the Mennonites and most of the other Germans, together with the arbitrary rule of many of the Palatine counts through the 18th century, were, no doubt, the main cause of the mass migration from this region at this time. But the Mennonites had added reasons for leaving what to them was a land of oppression. Not being one of the three tolerated religious groups guaranteed religious liberty by the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, they were subjected.to all sorts of humiliating civil disabilities and religious intolerance throughout the century. They had to pay an extra tax in the form of protection money; their expansion was limited to 200 families; their young men could not become members of the craft guilds and were thus unable to learn a trade; they were not allowed to live in cities except with special permission; they had only limited rights in the ownership of land; they were not allowed to marry except with the consent of the ruling authorities; nor were they permitted to be buried in the public cemeteries.

All the early Pennsylvania settlements were made in the southeastern corner of the province, within 100 miles of Philadelphia. As they expanded by natural increase and by the addition of new immigrants, and as the land became more valuable and scarce, the second and third generation descendants of the first colonists, as well as the newcomers, were compelled to find new homes farther out on the unoccupied frontiers. Mennonites were always among the pioneer settlers in new territory. As early as 1727 a group of Mennonites were found with the first German immigrants to the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia, although no permanent Mennonite settlement was made in Virginia until about 1780. In that state before the end of the century a number of flourishing congregations were located in the general region of Harrisonburg in what is now Rockingham County. Before 1800, too, the Pennsylvania Mennonites had established new homes along the Juniata in the center of the province, in south-central Franklin County, and in the southwestern corner near the headwaters of the Ohio River in Somerset County and Westmoreland County. In 1786 a number of Mennonites from Franklin County and later (1794) from Bucks and Lancaster found their way to Ontario, first near Niagara, then near what became Berlin, but now Kitchener, where they founded a major colony which has since grown into a large number of flourishing congregations, as well as smaller settlements in Lincoln County (Vineland) and in York County north of Toronto (Markham).

The Amish, too, expanded their settlement before the close of the century into the beautiful Kishacoquillas Valley in what is now Mifflin County, and into Somerset County. During the 19th century both the Mennonites and the Amish formed new congregations in a beeline westward in several states — Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, Kansas, and Nebraska.

State Relations

As long as the Quakers, who shared with the Mennonites their peace principles and their objection to the oath, retained control of the political machinery, the Pennsylvania government had a considerate regard for the religious scruples of the Mennonites on these questions. In 1717 a special act was passed by the Pennsylvania Assembly relieving Mennonites from any judicial oath; and in 1742 a similar act was passed in behalf of the Amish. In 1754 the Quakers lost control of the Assembly to the non-Quaker element of the population, and the peaceful policy inaugurated by Penn came to an end. During the French and Indian War (Seven Years' War) that followed there were many Indian depredations and massacres along the whole Pennsylvania frontier. Among those who lost their lives was an Amish family by the name of Hosteller. The influence of the Quakers, however, together with that of the other German nonresistant religious groups, was sufficiently strong to guarantee consideration on the part of the government for their special religious scruples throughout the 18th century. During the Revolutionary War Mennonites and others who shared their scruples against the bearing of arms were exempt from military duty upon the payment of a special small fee. When Pennsylvania, together with the other colonies, declared herself an independent state and free from England, demanding a new oath of allegiance from her citizens, some of the small Mennonite communities on the outer fringe of the larger settlements found some difficulty with the local authorities in maintaining their traditional principles regarding both war and the oath. Mennonites opposed the new oath on the grounds of opposition both to any oath at all and also to this new one in particular because it committed them to the support of revolution against constituted government, which was against their religious principles. In the small isolated congregation at Saucon in Lehigh County the whole male Mennonite population was at one time committed to jail for refusal to take the required oath. This was an exceptional case of persecution, however; in the larger, compact settlements, where the Mennonites were better known and understood by their local governments, no such drastic measures were resorted to, although all through the Revolutionary War the Mennonites, to whom respect for civil authority was a fundamental religious principle, were regarded by the super patriots of the time as unpatriotic and classed with the Loyalists. In 1790 the new state of Pennsylvania passed a law exempting the Mennonites from active militia duty upon the payment of a small fine.

While the Mennonites were unanimous in their refusal to bear arms, there was some difference in certain quarters on the question of paying the special war taxes required by the government. In 1778, Bishop Christian Funk, son of the pioneer Bishop Heinrich Funck, living in Indianfield Township in the Franconia region, insisted on the payment of the special tax, contrary to the general opinion of his fellow Mennonites of this region. As a result of this difference Funk was deposed by the fellowship and with some 52 followers organized an independent congregation that later came to be known as Funkite by those who disagreed with him. These Funkites retained their separate existence until 1850, when they became extinct.

Division

With the exception of the Funk controversy over war taxes, there were no serious controversies among the Mennonites during their first century in Pennsylvania. But during the 19th century there were a number of controversies, usually over minor questions of religious practice, that led to final separation and the organization of separate branches of the church. The first of these was a conservative division led by John Herr, which occurred in Lancaster County in 1812 and resulted in a group called the Reformed Mennonites. In 1957 there were only 309 members of this group in Pennsylvania in 10 congregations, 221 of whom lived in Lancaster County.

The second division, also a radically conservative one, occurred in Lancaster County in 1845, led by Jacob Stauffer, hence called Stauffer Mennonites. In 1957 the group had less than 300 members in 6 subdivisions.

The third division (General Conference Mennonite) occurred in the Franconia Conference in 1847, led by John H. Oberholtzer, a young minister who, together with his bishop, John Hunsicker, and a total of 16 of the 70 ministers of the district, because they insisted upon certain more liberal church practices than those in usage by the church at large at the time, were expelled from the Franconia Conference. The changes advocated by the Oberholtzer group included greater freedom in the choice of the cut of the clerical coat then required for the ministry; a more definite and prescribed form of procedure in conducting the sessions of the ministerial council meetings; and in general, a more liberal attitude toward all social and religious affiliation with the non-Mennonite world.

After its expulsion this group immediately formed a conference of its own, which later assumed the name "East Pennsylvania Conference of the Mennonite Church." Under the leadership of Oberholtzer the new conference adopted a progressive program of church extension, establishing Sunday schools, initiating a church paper, advocating an educational institution, and in the main advocating a more liberal association with other churches, both Mennonite and others, in their religious efforts. Oberholtzer was also greatly interested in the union into some sort of common ecclesiastical organization of all the scattered Mennonite churches throughout the country, and consistently advocated this cause in the church paper which he established in 1852, the Religiöser Botschafter. Some years later the congregations in this conference co-operated heartily in the movement that culminated in the formation in 1860 of the General Conference of the Mennonite Church of North America. Today these congregations form the Eastern District Conference of the General Conference. In 1957 its membership in Pennsylvania was 4,041 in 27 congregations.

The fourth division, the Mennonite Brethren in Christ, occurred in 1858, ten years after the Oberholtzer defection, as a division within a division. When William Gehman, a minister in the Upper Milford congregation of the newly organized East Pennsylvania Conference, together with a number of sympathizers, insisted on introducing regular midweek prayer meetings and other evangelistic practices not yet common among even the progressive Oberholtzer following, he was expelled from the conference. This group, too, soon formed a new organization under the name of Evangelical Mennonites. For a time they were few in number, but in the course of time, by joining with several other like-minded groups from Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, they formed, in 1883, a new branch of the church under the name of Mennonite Brethren in Christ. In 1947 this branch dropped the name Mennonite, and assumed the name United Missionary Church, but the Pennsylvania section, which forms a separate Pennsylvania conference, has retained the old name for the present. In 1957 it had 4,507 members in Pennsylvania in 35 congregations.

The fifth division was that of the Old Order Mennonites in Lancaster County in 1893, a part of a larger movement which included scattered groups of conservative Mennonites who, during the latter part of the 19th century, objected to what they considered some of the progressive religious practices then coming into general use among the Mennonite churches at large - Sunday schools, evangelistic meetings, mission meetings, more modern dress, in some cases the use of the English language in the pulpit, and other new religious observances more in keeping with the spirit of the times. In Lancaster they were first called "Martinites" after their leader Jonas H. Martin; in Indiana and Ohio they were called "Wislers" after their leader Jacob Wisler, who broke off in 1871-72; in Ontario the group broke off in 1889, in Virginia in 1900. In 1957 the Lancaster group, with several subdivisions, totaled 3,272 in 18 congregations.

Having lost these various divisions, the Mennonite Church (MC) constituted the main body in Pennsylvania. For convenience it is usually spoken of as the "Old" Mennonites, but the term "Old" is not official and is not recognized by the group. They have not been influenced much by these various defections. They are still largely conservative, especially in matters of dress and affiliation with other religious bodies, though quite progressive in mission work, Sunday schools, relief work, and other forms of progressive religious effort. As a whole they are more conservative in their religious practices than their brethren of the same branch in the states farther west. Their total membership in the state in 1957 was 26,580 distributed over the various district conferences as follows: Franconia, 5,311; Lancaster, 14,663; Allegheny, 2,721; Ohio and Eastern, 1,878; Franklin County, Pa., and Washington County, Md., 682; Conservative Conference, 438; independent congregations, 373; unaccounted for, 514.

Amish

The Amish in Pennsylvania divided ca. 1880 into two distinct groups, those who remained unchanged in their forms of worship and church life and practices and hence are called Old Order Amish, and those who followed a more progressive pattern and ultimately joined a Mennonite conference. The second group first joined the Eastern Amish Mennonite Conference in 1893, which merged with the Ohio Mennonite Conference into the Ohio and Eastern Mennonite Conference in 1925. Later several of these congregations transferred to the Allegheny Mennonite Conference. Some Old Order Amish (OOA) joined the Conservative Amish Conference, formed in 1910, and additional OOA groups withdrew to join the Beachy Amish movement which began in 1926. In 1957 the Beachy Amish had 692 members in Pennsylvania in 5 congregations. The Conservative Conference meanwhile had allied itself with the Mennonite Church (MC). The Old Order Amish in Pennsylvania in 1957 numbered 4,168 members in 52 congregations called "districts."

Situation in 1957

In 1957 Pennsylvania had the largest total number of Mennonites, 39,382, of any state in the Union, twice as large as Ohio, the next in size. This number was distributed by branches as follows:

| Mennonite Church (MC) | 26,580 |

| Old Order Amish | 4,168 |

| General Conference Mennonite Church | 4,061 |

| Old Order Mennonite | 3,272 |

| Beachy Amish | 692 |

| Reformed Mennonite | 309 |

| Stauffer Mennonite | 300 |

The Mennonite Brethren in Christ, who do not reckon themselves with the other Mennonite bodies, had 4,507 members in Pennsylvania in 1957. Thus the total in Pennsylvania carrying the name Mennonite was 43,889.

Institutions established in Pennsylvania by Mennonites include: Mennonite (MC) Publishing House at Scottdale (1908), four high schools (all MC) - Lancaster Mennonite School (1942), Johnstown Mennonite School (1944), Belleville Mennonite School (1945), Christopher Dock School (1954) at Lansdale, and 58 elementary schools operated by either the Amish or the Mennonites (MC) or in a few cases co-operatively by the two groups. Welfare institutions include the following: Mennonite Children's Home (1911) at Millersville, Mennonite Home (1905) at Lancaster, Welsh Mountain Samaritan Home (1898) near New Holland, Bethany Mennonite Home (1954) in Philadelphia, Eastern Mennonite Home (1916) at Souderton, Rockhill Mennonite Home (1955) at Sellersville, Eastern Mennonite Convalescent Home (1942) at Hatfield, and Philhaven Hospital for Mental and Nervous Diseases (1954) near Lebanon. All of these are under the Mennonite Church (MC). The General Conference Mennonites operate the Mennonite Home for the Aged (1896) at Frederick. The Mennonite Central Committee has had its headquarters at Akron, a village ten miles north of Lancaster, since 1937.

The Pennsylvania Mennonites, who were once exclusively rural and have made major contributions to American agriculture through the introduction from their Palatinate homeland of pioneer improvements such as crop rotation, nitrogenous legumes, etc., are now largely urbanized, possibly to 85 per cent. Many have entered into small businesses, a few have become manufacturers on a medium large scale, and an increasing number are entering the professions of teaching and medicine, only a very few into law, and none into politics. Many have become factory workers. The Amish and the Old Order Mennonites have remained exclusively rural.

The literary production of the Pennsylvania Mennonites has been slight, although in the 18th and early 19th centuries the German presses of Christopher Saur in Germantown, the Ephrata Cloister, and John Baer in Lancaster, published a considerable amount of German Mennonite literature including hymnals, catechisms, confessions, prayer-books, and the Martyrs' Mirror. The sole Mennonite press before the establishment of the Mennonite Publishing House at Scottdale in 1908 was the Mennonitischer Druckverein at Milford Square (1856 ff).

Characteristic Mennonite Names

The most common Mennonite names in Pennsylvania, all of the Swiss-Palatinate background except a very few who descend from the original Germantown settlers from the Lower Rhine, include the following (in modern spelling): Alderfer, Allebach, Bowman, Bleam, Beam, Brenneman, Brubaker, Baer, Bachman, Burkholder, Burkhart, Boyer, Bookwalter, Beyer, Bomberger, Bergey, Betzner, Breckbill, Bechtel, Beidler, Cassel, Clemmer, Clemens, Cressman, Eby, Erisman, Ebersole, Eschleman, Funk, Frey, Fretz, Frick, Freed, Frantz, Gehman, Gingrich, Groff, Good, Geil, Graybill, Glick, Huffman, Hunsicker, Holdeman, High, Hiestand, Hershey, Herr, Hess, Huber, Hagey, Horst, Hunsberger, Hallman, Hoover, Kolb, Kagey, Kratz, Kendig, Kreider, Keyser, Kaufman, Latschaw, Leatherman, Longenecker, Landes, Moyer, Miller, Musser, Musselman, Meylin, Martin, Mellinger, Metzler, Newcomer, Neff, Nissly, Nice, Oberholtzer, Pennypacker, Root, Rupp, Risser, Reist, Rittenhouse, Rosenberger, Swartley, Schantz, Souder, Stemen, Snavely, Shellenberger, Shenk, Stauffer, Snyder, Shoemaker, Shelly, Tyson, Weaver, Witmer, Wismer, Wenger, Wambold, [[Yoder (Ioder, Joder, Jodter, Jotter, Yoeder, Yother, Yothers, Yotter)|Yoder]], Zigler, and Zimmerman. The most common Pennsylvania Amish names include the following: Blough, Beiler, Borntreger, Coblentz, Detweiler, Kenagy, Fisher, Hooley, [[Hershberger (Hersberg, Hersberger, Herschberger, Hirschberger, Harshberger, Harshbarger)|Hershberger]], Hartzler, Hostetler, Kaufman, King, Lantz, Lapp, Miller, Mast, Plank, Peachey, Schrag, Stoltzfus, Smucker, Troyer, Umble, [[Yoder (Ioder, Joder, Jodter, Jotter, Yoeder, Yother, Yothers, Yotter)|Yoder]], and Zook.

Bibliography

Bender, H. S. "Founding of the Mennonite Church in America at Germantown, 1683-1708." Mennonite Quarterly Review VII (1933): 327-50.

Krehbiel, H. P. History of the General Conference of the Mennonite Church of North America. Canton, 1898.

Pennypacker, S. W. Historical and Biographical Sketches. Philadelphia, 1883.

Smith, C. Henry. Mennonites of America. Goshen, 1909.

Smith, C. Henry. Mennonite Immigration to Pennsylvania in the Eighteenth Century. Norristown, 1929.

Smith, C. Henry. The Story of the Mennonites. Berne, 1941.

Wenger, J. C. History of the Mennonites of the Franconia Conference. Telford, 1937.

Weaver, M. G. Mennonites of Lancaster Conference. Scottdale, 1931.

| Author(s) | C. Henry Smith |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1959 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Smith, C. Henry. "Pennsylvania (USA)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1959. Web. 3 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Pennsylvania_(USA)&oldid=101190.

APA style

Smith, C. Henry. (1959). Pennsylvania (USA). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 3 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Pennsylvania_(USA)&oldid=101190.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 4, pp. 136-141. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.