Difference between revisions of "West Prussia"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

SamSteiner (talk | contribs) m |

m (Added hyperlink.) |

||

| (17 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

__FORCETOC__ | __FORCETOC__ | ||

__TOC__ | __TOC__ | ||

| − | + | === Introduction === | |

| + | The area from west of [[Danzig (Poland)|Danzig]] to [[Elbing (Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, Poland)|Elbing]] and down along the Vistula River to [[Graudenz (Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland)|Graudenz]], Kulm, and [[Thorn (Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland)|Thorn]] encompasses the Vistula Delta and the northern portion of the river basin. [[Anabaptism|Anabaptist]] refugees settled here early in the 16th century and from the mid-17th century until 1945 it was home to the largest concentration of Mennonites in German territories. With migration from here to [[Russia]] starting in 1788 and to the [[United States of America|United States]] and [[Canada]] in 1874, it was also the place of origin for hundreds of Mennonite congregations now ranging from [[North America]] down to [[Uruguay]] and from western [[Germany]] across Central Asia to [[Siberia (Russia)|Siberia]]. | ||

| − | + | Originally inhabited by a Baltic tribe, the Old Prussians, the area was conquered and forcibly Christianized by the Teutonic Knights during the thirteenth century. In 1309 the Order moved its headquarters to the large castle at the beginning of the delta, the Marienburg, and ruled over a quasi-independent state along the Baltic Sea coast from Danzig to modern-day Estonia. In 1466 the Polish crown defeated the Knights and took their western territory away from them, at which time the territory became known as Polish or Royal Prussia, since a significant part of the land was now owned by the crown. In 1525 the remaining Teutonic territory became a duchy, Ducal Prussia, when the monastic order was dissolved. In 1618 the Hohenzollern family who ruled Brandenburg inherited that duchy and in 1657 removed it from under the sovereignty of the Polish Commonwealth. The name Prussia became attached to the Brandenburg state in 1701 when Elector Friedrich III won the right to call himself [[Friedrich I, King in Prussia (1657-1713)|Friedrich I, King in Prussia]], whenever he visited that territory. In 1772, [[Friedrich II, King of Prussia (1712-1786)|Friedrich II]], who now called himself King of Prussia, seized Royal Prussia as part of the First Partition of Prussia and changed the names of Royal and Ducal Prussia to West and [[East Prussia]] respectively. | |

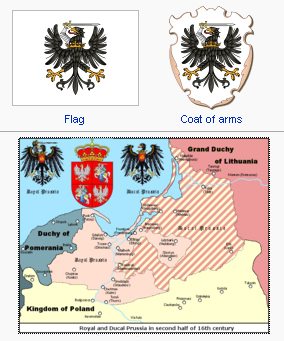

| − | [[File:RoyalPrussia.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Royal Prussia (light pink) in the second half of the | + | === The Origins of Mennonite Settlements in Royal Prussia === |

| + | [[File:RoyalPrussia.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Royal Prussia (light pink) in the second half of the 16th century.<br /> | ||

| + | Source: [http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Main_Page Wikipedia Commons]'']] | ||

| + | Although some local inhabitants showed early interest in radical Reformation ideas, Anabaptism took root in this area because of refugees seeking a place of toleration. Since this territory was outside the Holy Roman Empire, the edicts banning Anabaptism there did not apply. Given the ethnic and religious diversity already present, a decentralized state, and an agreement among elites to tolerant different confessions in order to avoid civil war, religious outsiders of many stripes, including Mennonites, were able to find toleration in the Polish Commonwealth by working out agreements with local authorities. [[Netherlands|The Netherlands]] dominated trade with [[Poland]] via the main port of Danzig at this time, buying grain and timber and selling cloth and other manufactured goods, making travel relatively easy for Anabaptist refugees, some of whom settled initially in and around the cities of Danzig and Elbing. [[Menno Simons (1496-1561)|Menno Simons]] visited here several times between 1547 and 1552 and in 1549 wrote a letter to the "congregation in Prussia." [[Dirk Philips (1504-1568)|Dirk Philips]], Menno’s closest co-worker, was considered the Elder of the Danzig congregation from 1561 to 1567, although he was on the move some in those years. The terminology "Mennonite" replaced "Anabaptist" in government documents starting in 1572. Mennonites had to settle outside the city walls in Danzig, gaining protection from the Bishop of Kujavia who was eager to avail himself of their craft production and the competition it provided for the city guilds. Their introduction of lace production was particularly important. In Elbing some Mennonites settled initially in the town itself. | ||

| − | + | In addition to those who came as refugees, there was strong interest among local elites in recruiting Dutch Mennonites for their skill in draining marshy land. The city of Danzig, for example, in 1547 sent Philip Edzema to the Low Countries to recruit settlers who could drain the swamps east of town. Mennonites arrived and developed several settlements centered on the village of Reichenberg just to the east of town. In the Greater Delta region between the Vistula and Nogat Rivers, Michael Loitz, a city councilor in Danzig, gave an important impetus to Mennonite settlement in the 1550s when he obtained the right to lease royal land to settlers in lieu of repayment for a loan he made to [[Sigismund II Augustus, King of Poland (1520-1572)|King Sigismund II Augustus]]. The Elbing lowlands west of the town were settled by Mennonites starting in 1550 when they were expelled from the town but allowed to settle nearby in the marshes of the Ellerwald that was owned by the citizens of Elbing. Some were soon able to settle in the town again, where from 1590 they owned a house church that is still standing. | |

| − | ( | + | === Mennonites in the Polish Commonwealth === |

| + | Mennonite existence in the Polish Commonwealth in the 17th and 18th centuries was marked by steady growth and ongoing maneuvers and conflicts between various levels of political authority. The Dutch split between [[Frisian Mennonites|Frisian]] and [[Flemish Mennonites|Flemish]] branches of Mennonites had come to Poland already in the 16th century and in Danzig two congregations resulted. The smaller Frisian group got its own church building in 1638 and the larger Flemish group followed in 1648; both buildings were outside the city walls. At first two elders oversaw their respective groups in the region, although the Frisians in [[Montau (Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland)|Montau]] up the river had their own Elder and building already in 1586. The rural Greater Delta Flemish got their own elder, Hans Siemans, in 1639. Initially this large congregation was centered in [[Rosenort (Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland)|Rosenort]] and met in houses and barns. In 1726 Elbing-Ellerwald had its first Elder, Hermann Jansson, and in 1728 in [[Heubuden (Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland)|Heubuden]] by [[Marienburg (Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland)|Marienburg]] the first Elder was [[Dyck, Jacob (1661-1748)|Jacob Dyck]]. In 1735 the large Greater Delta (Grosses Werder) Flemish congregation divided into four sectors, each with their own preachers and deacons, but retained a single, common Elder. Rosenort was able to build a church building in 1754 and on the first communion service held there on 2 March 1755, 1,566 members took communion. The other three sectors, [[Ladekopp (Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland)|Ladekopp]], [[Tiegenhagen (Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland)|Tiegenhagen]], and [[Fürstenwerder (Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland)|Fürstenwerder]], were finally able to build church buildings in 1768 as did Heubuden. By 1856 all four sectors had become independent congregations. An additional major milestone was issuing the first German-language Prussian Mennonite hymnal, ''[[Geistreiches Gesangbuch]]'', in 1767. | ||

| − | Source: [http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Main_Page Wikipedia Commons]'']] | + | [[File:WestPrussiaWik.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''West Prussia (red), within the Kingdom of Prussia (blue), within the German Empire (tan), as of 1878.<br /> |

| + | Source: [http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Main_Page Wikipedia Commons]'']] | ||

| − | + | The rural Greater Delta Frisian congregation in [[Orlofferfelde (Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland)|Orlofferfelde]] became independent in 1723. In addition to Montau there were Frisian congregations at [[Schönsee (Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland)|Schönsee]] near Culm and [[Thiensdorf and Preußisch Rosengart Mennonite Church (Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, Poland)|Thiensdorf]] south of Elbing. Members from there migrated to Ducal Prussia in the 1710s but were expelled in 1724 when their rejection of military service was discovered. They returned to Royal Prussia and started the last new settlement of Mennonites in the area, [[Tragheimerweide (Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland)|Tragheimerweide]], in the Vistula Valley south of the delta. Also in the valley near Culm was the congregation of [[Przechovka (Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland)|Wintersdorf/Przechowka]], a more conservative [[Old Flemish]] group. | |

| − | ( | + | Typical of the episodic problems Mennonites experienced with authorities was an investigation of Mennonites in Danzig. During the Swedish Deluge of 1655-1660 the Polish Commonwealth had been beset by non-Catholic invaders from all sides, leading to pressure on non-Catholics within the state and to the expulsion of the Polish Brethren, also called [[Socinianism|Socinians]] or [[Arians]] by their detractors. In general religious toleration declined since then as the outside pressures that began here continued until the partitions at the end of the 18th century. One consequence for Mennonites is that they too now came under greater scrutiny. In 1678 the royal court ordered an interrogation of the Mennonites in Danzig on suspicion of Socianism. The Bishop of Kujavia, Stanislaus Sarnowski, conducted the sessions in a house located on the main square, the Long Market, near the Artus Court. The elder of the Frisian Congregation, Hendrik van Dühren (1637-1694), who was a spice merchant living out in the suburb of Schidlitz since Mennonites were not allowed to settle within city walls, was examined on 17 January. [[Hansen, Georg (d. 1703)|Georg Hansen]], one of the pastors, spoke for the Flemish congregation on 20 January. At the end Hansen noted that Mennonites were freed from all suspicions. He added, however that "it cost us a serious amount of money which was very hard for us to raise, but God helped us to overcome it all." |

| − | + | As one can tell from Hansen’s comments, at different times Mennonites faced extra taxes, property confiscation, and even calls for expulsion as dangerous Anabaptists and heretics. For example, in 1642 Willibald von Haxberg used such threats to extort money from several Mennonite communities who then found backing and protection from their own landlords and finally from the king. Mennonites learned to appeal to different levels of authority in a decentralized state to find support. Yet Mennonites also stood under royal protection with [[Wladyslaw IV Vasa, King of Poland (1595-1648)|King Władysław IV]] in 1642 issuing the earliest extant royal Charter of Privilege granting Mennonites legal rights and freedoms. His decree mentions similar protections granted already by his grandfather, Sigismund II August, who ruled from 1548-72. In the decentralized Polish state at different times on different issues one authority would support Mennonites only to turn around and issue restrictions on them on other matters so that Mennonites became adapt at seeking out the most favorable source of backing among competing political actors. | |

| − | and Poland. | + | === Mennonites in the Kingdom of Prussia === |

| + | Between 1772 and 1795 the Polish Commonwealth disappeared from the map of Europe following a series of three partitions carried out by Prussia, [[Austria]], and Russia. Mennonites in West Prussia found themselves living under the King of Prussia. In 1772 Mennonites comprised 3 percent of the total West Prussian population but in Marienburg County in the heart of the Greater Delta where their settlements were concentrated, they were 10 percent of the population and controlled 25 percent of the land. They were immediately concerned about retaining their freedom to worship and to live as they had under Polish rule. In addition, they understood that they would face new pressure on military service, a topic of little relevance in Poland that had almost no standing army. They petitioned the incoming Prussian government for a new Charter of Privileges that they only obtained in 1780. Dealing with military service and fitting into German society became major preoccupations of the 19th century. | ||

| − | Source: Mennonite Encyclopedia, v. 4, p. 921.'']] | + | [[File:ME4_921.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Mennonite communities in West Prussia, East Prussia and Poland.<br /> |

| + | Source: Mennonite Encyclopedia, v. 4, p. 921.'']] | ||

| − | + | The Prussian government imposed a collective tax of 5,000 Reichsthaler per year that Mennonites had to pay in order to be exempted from the obligation to serve. The Mennonite congregations devised a system of charging each adult male and female a different set fee plus an additional charge on property in amounts that added up to the requires total. Since the state backed the obligation to pay with legal force, Mennonite leadership gained new powers and became more centralized in response to now living in a more powerful and centralized state. A new Mennonite Edict in 1789 created yet more taxes on Mennonites is support of the state church, made it illegal for outsiders to convert, even if they were married to a Mennonite, and formalized existing regulations that made it virtually impossible for Mennonites to acquire additional real estate. These restrictions on important civil rights made Mennonites strictly separate themselves from their surrounding society at a time when increasing economic activity and industrialization drove them to engage it. An early result of these contradictory Prussian policies was the start in 1788 of significant immigration to Russia, leading to the establishment of the [[Chortitza Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Chortitza Mennonite Settlement]], that continued at varying levels into the 1880s. Additional decrees in 1801 and 1803 first forbade female Mennonite land owners from retaining both their Mennonite status and their property before relenting and establishing an upper limit on the total value of real estate that Mennonites could ever own, but not before triggering the single largest wave of migration of Mennonites in 1803 to the new [[Molotschna Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Molotschna Mennonite Settlement]] in Russia. | |

| − | + | The latter years of the Napoleonic War were especially difficult for the community. After conquering Prussia in 1806 and turning it into a dependent satellite, [[Napoleon I, Emperor of France (1769-1821)|Napoleon]] launched his failed 1812 invasion of Russia from Prussian territory. Mennonite church services were cancelled in some places for three weeks in a row when in January 1813 the shattered remains of his army straggled back through the Mennonite settlements, making it too dangerous for people to be out. A hastily convoked Provincial Diet in nearby [[Königsberg (Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia)|Königsberg]] imposed the first modern draft in German history and the Mennonites struggled tenaciously to gain and maintain an exemption, paying an extra 30,000 Reichsthaler fee and gathering 500 horses to donate to the army. Following the 1848 revolutions the Mennonites again faced the threat of the draft, as the Frankfurt National Assembly wrote their draft constitution to explicitly require Mennonite military service, but that constitution was never instituted and [[Friedrich Wilhelm III, King of Prussia (1770-1840)|King Friedrich William III]] arbitrarily interpreted identical language incorporated into the Prussia constitution of 1850 as exempting the Mennonites. | |

| − | + | Several streams of religious thought impacted Prussian Mennonites in the 19th century. [[Pietism|Pietist]] influence was probably the most dominant one. Pastor Jahr of the [[Moravian Church|Moravian Brethren]] toured Mennonite churches already in 1810, by 1817 the Heubuden congregation was sending money to the Berlin Bible Society. In 1826 members of the Danzig and Heubuden congregation founded a school in Rodlofferhuben by Marienburg and in 1827 the Danzig Mission Society was founded with strong Mennonite support. In 1830 the Rodlofferhuben school held the first of what became large annual mission festivals. Both the school and the festivals moved in 1836 to Bröskerfelde after facing much hostility from Protestant clergy in Marienburg. These Neopietist Mennonites also tended to back conservative and monarchical politics. | |

| − | The | + | Rationalist and liberal thought also made inroads among Mennonites. The leading proponent of incorporating progressive interpretations of the Bible while promoting more democracy within the church and in society was [[Harder, Karl (1820-1898)|Carl Harder]], who grew up in Königsberg and at age 26 in 1846 became the first theologically educated, salaried pastor in his home church. Only the Danzig congregation, which had been created by the 1808 merger of the Flemish and Frisian congregations, also had paid pastors, starting with [[Smissen, Jacob II van der (1785-1846)|Jacob van der Smissen]] in 1827. Harder advocated letting individuals decide if they wanted to serve in the military or not, allowing marriages between Mennonites and non-Mennonites, improving the religious education of Mennonite children, started a short-lived Mennonite newspaper, and modified some additional traditional interpretations of the Bible. He preached on occasion in Elbing as well, causing a schism in the Elbing-Ellerwald congregation as some younger people wanted to hire him there, but no consensus could be found. The conflict brought unwanted government interference and Harder finally accepted a call to the congregation in Neuwied in 1858. He returned to Elbing in 1869 after changes in the government and among Mennonites made his style more acceptable. |

| − | + | Most Mennonites, of course, followed more traditional understandings when attempting to use modern possibilities to promote the faith. [[Mannhardt, Jakob (1801-1885)|Jakob Mannhardt]], pastor of the Danzig Mennonite Church from 1838 to his death in 1885, started the ''[[Mennonitische Blätter (Periodical)|Mennonitische Blätter]]'' in 1854 in an attempt to enliven the intellectual level and community spirit among Mennonites without borrowing so explicitly from either Pietists or Democrats. Rural Mennonites found even that move too unconventional and were slow to subscribe to the paper. | |

| − | + | === Mennonites after the Establishment of the German Empire === | |

| + | Prussia fought three wars from 1864 to 1870, resulting in the establishment of the German Empire in 1871. Once again Mennonites needed to make new arrangements in a new state. In 1867 the Parliament of the temporary North German Confederation imposed the draft on the Mennonites, explicitly mentioning them in their debates. A delegation of five elders met with King William I and many other officials seeking a restoration of their exemption, but significantly, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck refused to see them. In 1868 the King issued an executive order that allowed Mennonites to serve as noncombatants. Many petitions from Mennonites in support of and in opposition to the new arrangements followed and the community was bitterly divided. In 1874 the Imperial Parliament passed a Mennonite Law that rescinded most of the restrictions on Mennonites’ civil rights, although equality in taxation was not achieved until 1927. The same year traditionalists who could not accept military service in any form started leaving for the United States; migration to there and to Russia continued into the 1880s, involving roughly 15 percent of the total Mennonite population. | ||

| − | + | Those who stayed were now much freer to participate in economic opportunities and education. The urban congregations participated in forming the new [[Vereinigung der deutschen Mennonitengemeinden (Union of German Mennonite Congregations)|Vereinigung]] in 1886, rural congregations kept their distance from embracing this national institution until after the [[World War (1914-1918)|First World War]]. With so-called mixed marriages now accepted, new connections to society were possible, for example, Erich Göttner, whose father was Protestant, became pastor in the [[Danzig Mennonite Church (Gdansk, Poland)|Danzig Mennonite Church]] in 1927. Numerous Prussian Mennonites made contributions to German culture, to name just two examples, [[Mannhardt, Wilhelm (1831-1880)|Wilhelm Mannhardt]] in folklore studies and Hugo Conwentz as the founder of nature conservation. | |

| − | + | In World War I Mennonites mostly participated as combat soldiers, less than one third still took advantage of the legal opportunity to serve as [[Nonresistance|non-combatants]]. Nationwide, 91 Mennonites had been awarded the Iron Cross and 144 killed in action by November 1915 when the ''Mennonitische Blätter'' on government orders stopped printing casualty and medal awardee lists. After World War I, these congregations were split between three different states. Most belonged to the [[Danzig, Free City of|Free State of Danzig]], which was created as a buffer between [[Germany]] and [[Poland]] in the Treaty of Versailles. Those up the Vistula River were now in Poland while the congregations east of the Nogat River were incorporated into the German enclave of East Prussia. Mennonites like other Germans in these territories deeply resented the impositions of the foreign peace settlement and were suspicious of the Weimar Republic that replaced the Empire and was led by the Socialist Democratic Party. | |

| − | + | === Nazi Rule, War, and Dissolution of the Congregations === | |

| + | In the 1930s Mennonites were still largely rural and their strong identification with Germany, more direct knowledge of the terror imposed on Mennonites in the [[Soviet Union]], and disgust with the Versailles Treaty arrangements made support for the Third Reich and its pro-agricultural and anti-communist policies seem natural. [[National Socialism (Nazism) (Germany)|Nazis]] won the elections in the Free State in June 1933 and tried to mirror Hitler’s rule in this small territory, although League of Nations oversight prevented some of their moves. More directly relevant to the churches were the struggles over the alignment of Mennonite theology with Nazi ideology in a way similar to what was known as the Kirchenkampf among German Protestants. Pastor Erich Göttner in Danzig was in touch with the Confessing Church that opposed conflating Nazi racial ideology with theology and strongly opposed such moves. They were successful in averting a feared takeover of Mennonite church institutions by Nazi Protestants. Outside of narrowly defined church concerns, they were eager to seem supportive of government and agreed already in 1933, two years before the draft was imposed in Germany, not to seek any exemption. Those in Polish territory were drafted into the Polish army, so that Mennonites from the same community were in opposing armies on 1 September 1939, when Germany invaded Poland with the first shots being fired in Danzig. At the start of the war a concentration camp was opened at Stutthof and a number of Mennonite farmers and businesses used inmates as slave labor. When Hitler was received in the Artushof on 19 September 1939, the Mennonite Landrat Walter Neufeldt was part of the official delegation. Abraham Esau from Tiegenhagen led Germany’s nuclear physics efforts in 1942 and 1943 and work on radar systems after that. | ||

| − | In the | + | Many Mennonites served and died in the army; exact figures are unknown. In summer 1943 30,000 Mennonites from Russia were resettled in the Warthegau district south of West Prussia and contacts were made to support them. In January 1945, with the front approaching, the order was given for evacuations to the west for the roughly [[Danzig Refugees|10,000 Mennonites of West Prussia]]. About 1,800 ended up being shipped to [[Denmark]] where [[Mennonite Central Committee (International)|Mennonite Central Committee]] workers began assisting them in September 1945. In 1948, 700 of these departed for new lives in Uruguay, including Elders Bruno Ewert and [[Regehr, Ernst (1903-1970)|Ernst Regehr]]. The British Occupation Zone in northwest Germany had about 5,500 when a count was done in 1948, about a thousand were in the American and French Zones, perhaps that many again were still in the Soviet Zone, and another thousand were presumed to have died en route. MCC helped create new settlements for these refugees in [[Backnang (Baden-Württemberg, Germany)|Backnang]], [[Bechterdissen (Leopoldshöhe, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)|Bechterdissen]] by [[Bielefeld (Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)|Bielefeld]], [[Enkenbach (Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany)|Enkenbach]], [[Wedel (Schleswig-Holstein, Germany)|Wedel]] near Hamburg, [[Espelkamp (Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)|Espelkamp]], and Torney by [[Neuwied (Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany)|Neuwied]] among others. The congregations were all scattered and the Mennonite church buildings and cemeteries abandoned – the territory now incorporated into Poland. |

| − | The | + | The Cold War, the Communist government in Poland, and tense German-Polish relations made visits to the former West Prussia impossible at first, difficult later, and after 1990 popular with tourists. With a great deal of effort Pentecostals in Danzig managed to obtain possession of the former Danzig Mennonite Church building, restoring it for use as a place of worship in 1958. Catholics now use the churches in Preussisch Rosengart, Montau, and [[Obernessau (Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland)|Obernessau]], the National Polish Catholic Church uses the church built in Elbing for Carl Harder’s congregation. Most of the other church buildings have been destroyed. Since 1990 local people, most who have roots in western Ukraine and were settled here after the war as refugees themselves, have taken renewed interest in the Mennonite heritage of the Vistula Delta and work with international Mennonite groups such as the Mennonitischer Arbeitskreis Polen and the Mennonite Polish Studies Association to preserve this history. |

| − | + | == Bibliography == | |

| + | Bömelburg, Hans-Jürgen. ''Zwischen Polnischer Ständegesellschaft und Preussischenm Obrigskeitsstaat. Vom Königlichen Preußen zu Westpreußen (1756-1806)''. München: R. Oldenbourg Verlag, 1995. | ||

| − | + | Friedrich, Karin. ''The Other Prussia: Royal Prussia, Poland and Liberty, 1569-1772''. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000. | |

| − | + | Jantzen, Mark. "Wealth and Power in the Vistula River Mennonite Community, 1772-1914" in ''Journal of Mennonite Studies'' (2009): 93-108. | |

| − | + | Jantzen, Mark. ''Mennonite German Soldiers: Nation, Religion, and Family in the Prussian East, 1772-1880''. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2010. | |

| − | + | Klassen, Peter J. ''A Homeland for Strangers. An Introduction to Mennonites in Poland and Prussia''. Rev. ed. Fresno, CA: Center for Mennonite Brethren Studies, 2011. | |

| − | + | Klassen, Peter J. ''Mennonites in Early Modern Poland and Prussia''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009. | |

| − | + | Ludwig, Karl-Heinz. ''Zur Besiedlung des Weichseldeltas durch die Mennoniten: die Siedlungen der Mennoniten im Territorium der Stadt Elbing und in der Ökonomie Marienburg bis zur Übernahme der Gebiete durch Preussen 1772''. Marburg: Johann Gottfried Herder-Institut, 1961. | |

| − | + | Mannhardt, Hermann G. ''Die Danziger Mennonitengemeinde. Ihre Entstehung und ihre Geschichte von 1569-1919''. Danzig: Danziger Mennonitengemeinde, 1919. | |

| − | + | Mannhardt, Wilhelm. ''Die Wehrfreiheit der altpreussischen Mennoniten. Eine geschichliche Erörterung''. Marienburg: In Commission bei B. Hermann Hemmpels Wwe., 1863. | |

| − | + | Penner, Horst. "Westpreussen" in ''Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967'', vol. IV: 504-20. | |

| − | + | Penner, Horst. ''Die ost-und westpreußischen Mennoniten in ihrem religiösen und sozialen Leben in ihren kulturellen und wirtschaftlichen Leistungen''. 2 vols. Weierhof, Germany: Mennonitischer Geschichtsverien e.V., 1978, 1987. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Wiebe, Herbert. ''Das Siedlungswerk niederländischer Mennoniten in Weichseltal zwischen Fordon und Weissenberg bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts''. Marburg: Johann Gottfried Herder-Institut, 1952. | |

| − | + | == Additional Information == | |

| − | + | This article is based on the original English article that was written for the [http://www.mennlex.de/doku.php Mennonitisches Lexikon] (MennLex) and has been made available to GAMEO with permission. The German version of this article is available at: https://www.mennlex.de/doku.php?id=loc:westpreussen | |

| − | + | {{GAMEO_footer|hp=|date=January 2026|a1_last=Jantzen|a1_first=Mark|a2_last=|a2_first=}} | |

| − | + | [[Category:Places]] | |

| − | + | [[Category:Countries]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{GAMEO_footer|hp= | ||

Latest revision as of 21:10, 17 January 2026

Introduction

The area from west of Danzig to Elbing and down along the Vistula River to Graudenz, Kulm, and Thorn encompasses the Vistula Delta and the northern portion of the river basin. Anabaptist refugees settled here early in the 16th century and from the mid-17th century until 1945 it was home to the largest concentration of Mennonites in German territories. With migration from here to Russia starting in 1788 and to the United States and Canada in 1874, it was also the place of origin for hundreds of Mennonite congregations now ranging from North America down to Uruguay and from western Germany across Central Asia to Siberia.

Originally inhabited by a Baltic tribe, the Old Prussians, the area was conquered and forcibly Christianized by the Teutonic Knights during the thirteenth century. In 1309 the Order moved its headquarters to the large castle at the beginning of the delta, the Marienburg, and ruled over a quasi-independent state along the Baltic Sea coast from Danzig to modern-day Estonia. In 1466 the Polish crown defeated the Knights and took their western territory away from them, at which time the territory became known as Polish or Royal Prussia, since a significant part of the land was now owned by the crown. In 1525 the remaining Teutonic territory became a duchy, Ducal Prussia, when the monastic order was dissolved. In 1618 the Hohenzollern family who ruled Brandenburg inherited that duchy and in 1657 removed it from under the sovereignty of the Polish Commonwealth. The name Prussia became attached to the Brandenburg state in 1701 when Elector Friedrich III won the right to call himself Friedrich I, King in Prussia, whenever he visited that territory. In 1772, Friedrich II, who now called himself King of Prussia, seized Royal Prussia as part of the First Partition of Prussia and changed the names of Royal and Ducal Prussia to West and East Prussia respectively.

The Origins of Mennonite Settlements in Royal Prussia

Although some local inhabitants showed early interest in radical Reformation ideas, Anabaptism took root in this area because of refugees seeking a place of toleration. Since this territory was outside the Holy Roman Empire, the edicts banning Anabaptism there did not apply. Given the ethnic and religious diversity already present, a decentralized state, and an agreement among elites to tolerant different confessions in order to avoid civil war, religious outsiders of many stripes, including Mennonites, were able to find toleration in the Polish Commonwealth by working out agreements with local authorities. The Netherlands dominated trade with Poland via the main port of Danzig at this time, buying grain and timber and selling cloth and other manufactured goods, making travel relatively easy for Anabaptist refugees, some of whom settled initially in and around the cities of Danzig and Elbing. Menno Simons visited here several times between 1547 and 1552 and in 1549 wrote a letter to the "congregation in Prussia." Dirk Philips, Menno’s closest co-worker, was considered the Elder of the Danzig congregation from 1561 to 1567, although he was on the move some in those years. The terminology "Mennonite" replaced "Anabaptist" in government documents starting in 1572. Mennonites had to settle outside the city walls in Danzig, gaining protection from the Bishop of Kujavia who was eager to avail himself of their craft production and the competition it provided for the city guilds. Their introduction of lace production was particularly important. In Elbing some Mennonites settled initially in the town itself.

In addition to those who came as refugees, there was strong interest among local elites in recruiting Dutch Mennonites for their skill in draining marshy land. The city of Danzig, for example, in 1547 sent Philip Edzema to the Low Countries to recruit settlers who could drain the swamps east of town. Mennonites arrived and developed several settlements centered on the village of Reichenberg just to the east of town. In the Greater Delta region between the Vistula and Nogat Rivers, Michael Loitz, a city councilor in Danzig, gave an important impetus to Mennonite settlement in the 1550s when he obtained the right to lease royal land to settlers in lieu of repayment for a loan he made to King Sigismund II Augustus. The Elbing lowlands west of the town were settled by Mennonites starting in 1550 when they were expelled from the town but allowed to settle nearby in the marshes of the Ellerwald that was owned by the citizens of Elbing. Some were soon able to settle in the town again, where from 1590 they owned a house church that is still standing.

Mennonites in the Polish Commonwealth

Mennonite existence in the Polish Commonwealth in the 17th and 18th centuries was marked by steady growth and ongoing maneuvers and conflicts between various levels of political authority. The Dutch split between Frisian and Flemish branches of Mennonites had come to Poland already in the 16th century and in Danzig two congregations resulted. The smaller Frisian group got its own church building in 1638 and the larger Flemish group followed in 1648; both buildings were outside the city walls. At first two elders oversaw their respective groups in the region, although the Frisians in Montau up the river had their own Elder and building already in 1586. The rural Greater Delta Flemish got their own elder, Hans Siemans, in 1639. Initially this large congregation was centered in Rosenort and met in houses and barns. In 1726 Elbing-Ellerwald had its first Elder, Hermann Jansson, and in 1728 in Heubuden by Marienburg the first Elder was Jacob Dyck. In 1735 the large Greater Delta (Grosses Werder) Flemish congregation divided into four sectors, each with their own preachers and deacons, but retained a single, common Elder. Rosenort was able to build a church building in 1754 and on the first communion service held there on 2 March 1755, 1,566 members took communion. The other three sectors, Ladekopp, Tiegenhagen, and Fürstenwerder, were finally able to build church buildings in 1768 as did Heubuden. By 1856 all four sectors had become independent congregations. An additional major milestone was issuing the first German-language Prussian Mennonite hymnal, Geistreiches Gesangbuch, in 1767.

Source: Wikipedia Commons

The rural Greater Delta Frisian congregation in Orlofferfelde became independent in 1723. In addition to Montau there were Frisian congregations at Schönsee near Culm and Thiensdorf south of Elbing. Members from there migrated to Ducal Prussia in the 1710s but were expelled in 1724 when their rejection of military service was discovered. They returned to Royal Prussia and started the last new settlement of Mennonites in the area, Tragheimerweide, in the Vistula Valley south of the delta. Also in the valley near Culm was the congregation of Wintersdorf/Przechowka, a more conservative Old Flemish group.

Typical of the episodic problems Mennonites experienced with authorities was an investigation of Mennonites in Danzig. During the Swedish Deluge of 1655-1660 the Polish Commonwealth had been beset by non-Catholic invaders from all sides, leading to pressure on non-Catholics within the state and to the expulsion of the Polish Brethren, also called Socinians or Arians by their detractors. In general religious toleration declined since then as the outside pressures that began here continued until the partitions at the end of the 18th century. One consequence for Mennonites is that they too now came under greater scrutiny. In 1678 the royal court ordered an interrogation of the Mennonites in Danzig on suspicion of Socianism. The Bishop of Kujavia, Stanislaus Sarnowski, conducted the sessions in a house located on the main square, the Long Market, near the Artus Court. The elder of the Frisian Congregation, Hendrik van Dühren (1637-1694), who was a spice merchant living out in the suburb of Schidlitz since Mennonites were not allowed to settle within city walls, was examined on 17 January. Georg Hansen, one of the pastors, spoke for the Flemish congregation on 20 January. At the end Hansen noted that Mennonites were freed from all suspicions. He added, however that "it cost us a serious amount of money which was very hard for us to raise, but God helped us to overcome it all."

As one can tell from Hansen’s comments, at different times Mennonites faced extra taxes, property confiscation, and even calls for expulsion as dangerous Anabaptists and heretics. For example, in 1642 Willibald von Haxberg used such threats to extort money from several Mennonite communities who then found backing and protection from their own landlords and finally from the king. Mennonites learned to appeal to different levels of authority in a decentralized state to find support. Yet Mennonites also stood under royal protection with King Władysław IV in 1642 issuing the earliest extant royal Charter of Privilege granting Mennonites legal rights and freedoms. His decree mentions similar protections granted already by his grandfather, Sigismund II August, who ruled from 1548-72. In the decentralized Polish state at different times on different issues one authority would support Mennonites only to turn around and issue restrictions on them on other matters so that Mennonites became adapt at seeking out the most favorable source of backing among competing political actors.

Mennonites in the Kingdom of Prussia

Between 1772 and 1795 the Polish Commonwealth disappeared from the map of Europe following a series of three partitions carried out by Prussia, Austria, and Russia. Mennonites in West Prussia found themselves living under the King of Prussia. In 1772 Mennonites comprised 3 percent of the total West Prussian population but in Marienburg County in the heart of the Greater Delta where their settlements were concentrated, they were 10 percent of the population and controlled 25 percent of the land. They were immediately concerned about retaining their freedom to worship and to live as they had under Polish rule. In addition, they understood that they would face new pressure on military service, a topic of little relevance in Poland that had almost no standing army. They petitioned the incoming Prussian government for a new Charter of Privileges that they only obtained in 1780. Dealing with military service and fitting into German society became major preoccupations of the 19th century.

The Prussian government imposed a collective tax of 5,000 Reichsthaler per year that Mennonites had to pay in order to be exempted from the obligation to serve. The Mennonite congregations devised a system of charging each adult male and female a different set fee plus an additional charge on property in amounts that added up to the requires total. Since the state backed the obligation to pay with legal force, Mennonite leadership gained new powers and became more centralized in response to now living in a more powerful and centralized state. A new Mennonite Edict in 1789 created yet more taxes on Mennonites is support of the state church, made it illegal for outsiders to convert, even if they were married to a Mennonite, and formalized existing regulations that made it virtually impossible for Mennonites to acquire additional real estate. These restrictions on important civil rights made Mennonites strictly separate themselves from their surrounding society at a time when increasing economic activity and industrialization drove them to engage it. An early result of these contradictory Prussian policies was the start in 1788 of significant immigration to Russia, leading to the establishment of the Chortitza Mennonite Settlement, that continued at varying levels into the 1880s. Additional decrees in 1801 and 1803 first forbade female Mennonite land owners from retaining both their Mennonite status and their property before relenting and establishing an upper limit on the total value of real estate that Mennonites could ever own, but not before triggering the single largest wave of migration of Mennonites in 1803 to the new Molotschna Mennonite Settlement in Russia.

The latter years of the Napoleonic War were especially difficult for the community. After conquering Prussia in 1806 and turning it into a dependent satellite, Napoleon launched his failed 1812 invasion of Russia from Prussian territory. Mennonite church services were cancelled in some places for three weeks in a row when in January 1813 the shattered remains of his army straggled back through the Mennonite settlements, making it too dangerous for people to be out. A hastily convoked Provincial Diet in nearby Königsberg imposed the first modern draft in German history and the Mennonites struggled tenaciously to gain and maintain an exemption, paying an extra 30,000 Reichsthaler fee and gathering 500 horses to donate to the army. Following the 1848 revolutions the Mennonites again faced the threat of the draft, as the Frankfurt National Assembly wrote their draft constitution to explicitly require Mennonite military service, but that constitution was never instituted and King Friedrich William III arbitrarily interpreted identical language incorporated into the Prussia constitution of 1850 as exempting the Mennonites.

Several streams of religious thought impacted Prussian Mennonites in the 19th century. Pietist influence was probably the most dominant one. Pastor Jahr of the Moravian Brethren toured Mennonite churches already in 1810, by 1817 the Heubuden congregation was sending money to the Berlin Bible Society. In 1826 members of the Danzig and Heubuden congregation founded a school in Rodlofferhuben by Marienburg and in 1827 the Danzig Mission Society was founded with strong Mennonite support. In 1830 the Rodlofferhuben school held the first of what became large annual mission festivals. Both the school and the festivals moved in 1836 to Bröskerfelde after facing much hostility from Protestant clergy in Marienburg. These Neopietist Mennonites also tended to back conservative and monarchical politics.

Rationalist and liberal thought also made inroads among Mennonites. The leading proponent of incorporating progressive interpretations of the Bible while promoting more democracy within the church and in society was Carl Harder, who grew up in Königsberg and at age 26 in 1846 became the first theologically educated, salaried pastor in his home church. Only the Danzig congregation, which had been created by the 1808 merger of the Flemish and Frisian congregations, also had paid pastors, starting with Jacob van der Smissen in 1827. Harder advocated letting individuals decide if they wanted to serve in the military or not, allowing marriages between Mennonites and non-Mennonites, improving the religious education of Mennonite children, started a short-lived Mennonite newspaper, and modified some additional traditional interpretations of the Bible. He preached on occasion in Elbing as well, causing a schism in the Elbing-Ellerwald congregation as some younger people wanted to hire him there, but no consensus could be found. The conflict brought unwanted government interference and Harder finally accepted a call to the congregation in Neuwied in 1858. He returned to Elbing in 1869 after changes in the government and among Mennonites made his style more acceptable.

Most Mennonites, of course, followed more traditional understandings when attempting to use modern possibilities to promote the faith. Jakob Mannhardt, pastor of the Danzig Mennonite Church from 1838 to his death in 1885, started the Mennonitische Blätter in 1854 in an attempt to enliven the intellectual level and community spirit among Mennonites without borrowing so explicitly from either Pietists or Democrats. Rural Mennonites found even that move too unconventional and were slow to subscribe to the paper.

Mennonites after the Establishment of the German Empire

Prussia fought three wars from 1864 to 1870, resulting in the establishment of the German Empire in 1871. Once again Mennonites needed to make new arrangements in a new state. In 1867 the Parliament of the temporary North German Confederation imposed the draft on the Mennonites, explicitly mentioning them in their debates. A delegation of five elders met with King William I and many other officials seeking a restoration of their exemption, but significantly, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck refused to see them. In 1868 the King issued an executive order that allowed Mennonites to serve as noncombatants. Many petitions from Mennonites in support of and in opposition to the new arrangements followed and the community was bitterly divided. In 1874 the Imperial Parliament passed a Mennonite Law that rescinded most of the restrictions on Mennonites’ civil rights, although equality in taxation was not achieved until 1927. The same year traditionalists who could not accept military service in any form started leaving for the United States; migration to there and to Russia continued into the 1880s, involving roughly 15 percent of the total Mennonite population.

Those who stayed were now much freer to participate in economic opportunities and education. The urban congregations participated in forming the new Vereinigung in 1886, rural congregations kept their distance from embracing this national institution until after the First World War. With so-called mixed marriages now accepted, new connections to society were possible, for example, Erich Göttner, whose father was Protestant, became pastor in the Danzig Mennonite Church in 1927. Numerous Prussian Mennonites made contributions to German culture, to name just two examples, Wilhelm Mannhardt in folklore studies and Hugo Conwentz as the founder of nature conservation.

In World War I Mennonites mostly participated as combat soldiers, less than one third still took advantage of the legal opportunity to serve as non-combatants. Nationwide, 91 Mennonites had been awarded the Iron Cross and 144 killed in action by November 1915 when the Mennonitische Blätter on government orders stopped printing casualty and medal awardee lists. After World War I, these congregations were split between three different states. Most belonged to the Free State of Danzig, which was created as a buffer between Germany and Poland in the Treaty of Versailles. Those up the Vistula River were now in Poland while the congregations east of the Nogat River were incorporated into the German enclave of East Prussia. Mennonites like other Germans in these territories deeply resented the impositions of the foreign peace settlement and were suspicious of the Weimar Republic that replaced the Empire and was led by the Socialist Democratic Party.

Nazi Rule, War, and Dissolution of the Congregations

In the 1930s Mennonites were still largely rural and their strong identification with Germany, more direct knowledge of the terror imposed on Mennonites in the Soviet Union, and disgust with the Versailles Treaty arrangements made support for the Third Reich and its pro-agricultural and anti-communist policies seem natural. Nazis won the elections in the Free State in June 1933 and tried to mirror Hitler’s rule in this small territory, although League of Nations oversight prevented some of their moves. More directly relevant to the churches were the struggles over the alignment of Mennonite theology with Nazi ideology in a way similar to what was known as the Kirchenkampf among German Protestants. Pastor Erich Göttner in Danzig was in touch with the Confessing Church that opposed conflating Nazi racial ideology with theology and strongly opposed such moves. They were successful in averting a feared takeover of Mennonite church institutions by Nazi Protestants. Outside of narrowly defined church concerns, they were eager to seem supportive of government and agreed already in 1933, two years before the draft was imposed in Germany, not to seek any exemption. Those in Polish territory were drafted into the Polish army, so that Mennonites from the same community were in opposing armies on 1 September 1939, when Germany invaded Poland with the first shots being fired in Danzig. At the start of the war a concentration camp was opened at Stutthof and a number of Mennonite farmers and businesses used inmates as slave labor. When Hitler was received in the Artushof on 19 September 1939, the Mennonite Landrat Walter Neufeldt was part of the official delegation. Abraham Esau from Tiegenhagen led Germany’s nuclear physics efforts in 1942 and 1943 and work on radar systems after that.

Many Mennonites served and died in the army; exact figures are unknown. In summer 1943 30,000 Mennonites from Russia were resettled in the Warthegau district south of West Prussia and contacts were made to support them. In January 1945, with the front approaching, the order was given for evacuations to the west for the roughly 10,000 Mennonites of West Prussia. About 1,800 ended up being shipped to Denmark where Mennonite Central Committee workers began assisting them in September 1945. In 1948, 700 of these departed for new lives in Uruguay, including Elders Bruno Ewert and Ernst Regehr. The British Occupation Zone in northwest Germany had about 5,500 when a count was done in 1948, about a thousand were in the American and French Zones, perhaps that many again were still in the Soviet Zone, and another thousand were presumed to have died en route. MCC helped create new settlements for these refugees in Backnang, Bechterdissen by Bielefeld, Enkenbach, Wedel near Hamburg, Espelkamp, and Torney by Neuwied among others. The congregations were all scattered and the Mennonite church buildings and cemeteries abandoned – the territory now incorporated into Poland.

The Cold War, the Communist government in Poland, and tense German-Polish relations made visits to the former West Prussia impossible at first, difficult later, and after 1990 popular with tourists. With a great deal of effort Pentecostals in Danzig managed to obtain possession of the former Danzig Mennonite Church building, restoring it for use as a place of worship in 1958. Catholics now use the churches in Preussisch Rosengart, Montau, and Obernessau, the National Polish Catholic Church uses the church built in Elbing for Carl Harder’s congregation. Most of the other church buildings have been destroyed. Since 1990 local people, most who have roots in western Ukraine and were settled here after the war as refugees themselves, have taken renewed interest in the Mennonite heritage of the Vistula Delta and work with international Mennonite groups such as the Mennonitischer Arbeitskreis Polen and the Mennonite Polish Studies Association to preserve this history.

Bibliography

Bömelburg, Hans-Jürgen. Zwischen Polnischer Ständegesellschaft und Preussischenm Obrigskeitsstaat. Vom Königlichen Preußen zu Westpreußen (1756-1806). München: R. Oldenbourg Verlag, 1995.

Friedrich, Karin. The Other Prussia: Royal Prussia, Poland and Liberty, 1569-1772. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Jantzen, Mark. "Wealth and Power in the Vistula River Mennonite Community, 1772-1914" in Journal of Mennonite Studies (2009): 93-108.

Jantzen, Mark. Mennonite German Soldiers: Nation, Religion, and Family in the Prussian East, 1772-1880. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2010.

Klassen, Peter J. A Homeland for Strangers. An Introduction to Mennonites in Poland and Prussia. Rev. ed. Fresno, CA: Center for Mennonite Brethren Studies, 2011.

Klassen, Peter J. Mennonites in Early Modern Poland and Prussia. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009.

Ludwig, Karl-Heinz. Zur Besiedlung des Weichseldeltas durch die Mennoniten: die Siedlungen der Mennoniten im Territorium der Stadt Elbing und in der Ökonomie Marienburg bis zur Übernahme der Gebiete durch Preussen 1772. Marburg: Johann Gottfried Herder-Institut, 1961.

Mannhardt, Hermann G. Die Danziger Mennonitengemeinde. Ihre Entstehung und ihre Geschichte von 1569-1919. Danzig: Danziger Mennonitengemeinde, 1919.

Mannhardt, Wilhelm. Die Wehrfreiheit der altpreussischen Mennoniten. Eine geschichliche Erörterung. Marienburg: In Commission bei B. Hermann Hemmpels Wwe., 1863.

Penner, Horst. "Westpreussen" in Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967, vol. IV: 504-20.

Penner, Horst. Die ost-und westpreußischen Mennoniten in ihrem religiösen und sozialen Leben in ihren kulturellen und wirtschaftlichen Leistungen. 2 vols. Weierhof, Germany: Mennonitischer Geschichtsverien e.V., 1978, 1987.

Wiebe, Herbert. Das Siedlungswerk niederländischer Mennoniten in Weichseltal zwischen Fordon und Weissenberg bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts. Marburg: Johann Gottfried Herder-Institut, 1952.

Additional Information

This article is based on the original English article that was written for the Mennonitisches Lexikon (MennLex) and has been made available to GAMEO with permission. The German version of this article is available at: https://www.mennlex.de/doku.php?id=loc:westpreussen

| Author(s) | Mark Jantzen |

|---|---|

| Date Published | January 2026 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Jantzen, Mark. "West Prussia." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. January 2026. Web. 1 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=West_Prussia&oldid=181477.

APA style

Jantzen, Mark. (January 2026). West Prussia. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 1 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=West_Prussia&oldid=181477.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.