Paraguay

Introduction

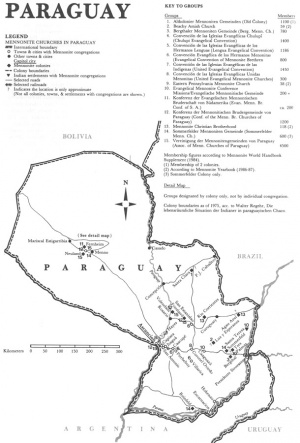

The Republic of Paraguay is a landlocked country in South America, bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to the east and northeast, and Bolivia to the northwest. The area of Paraguay is 406,752 km2 (157,048 square miles). The Paraguay River (Rio Paraguay) runs through the center of the country from north to south and divides the country into two regions, Eastern Paraguay (also known as the Paraná region) and Western Paraguay (also known as the Chaco).

Paraguay was first settled by semi-nomadic tribes called the Guaraní people. The first Europeans arrived from Spain in 1516. Paraguay became independent from Spain in 1811 and from Argentina in 1842. The nation's governments have been dominated by dictatorships and short-lived governments who presidents were often removed from office by force. Paraguay fought against Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay from 1864 to 1870 and suffered terrible losses of life. The Chaco War with Bolivia in the 1930s resulted in the re-establishment of soveriegnty over the Chaco region.

As of 2011 the population was estimated at 6,561,748. The capital and largest city is Asunción. The official languages are Spanish and Guaraní, both being widely spoken in the country. Approximately 80% of the population are Mestizo (mixed European and Amerindian).

According to the 2002 census, 89.6% of the population is Roman Catholic, 6.2% is Evangelical Christian, 1.1% is other Christian, and 0.6% practice indigenous religions.

1959 Article

The Tropic of Capricorn runs through Paraguay at the line where almost equal parts lie on either side. Most of Paraguay proper, however, i.e., the part east of the Paraguay River, lies south of the line. Most of the Paraguayan Chaco, that part of the country west of the Paraguay River, lies in the Torrid Zone. The climate is, therefore, tropical and subtropical. Much of the year is mild, but there is a range from cool to very hot. In the summer months of December, January, and February the temperature frequently rises above 100° Fahrenheit (38° Celsius). It can also be hot in other months of the year, even in midwinter. Occasionally there are frosts even on the torrid side of Capricorn. In the drier winter months some parts of the country are at times subject to hot north winds and dust storms. The Paraguay River divides the country into unequal and quite different parts, the eastern section being more rolling and having more rainfall than the western. From the Paraguay River, where the elevation is low, to the Brazilian border on the east, the elevation rises to some highlands which average 1,500 feet or more above sea level. Unlike most of South America, Paraguay has no real mountains. Since transportation facilities within the country were very inadequate, the Paraguay and Parana Rivers were doubly important as channels of commerce.

The natural resources of Paraguay make it well fitted for agriculture. There was some industry in the 1950s and there probably will be more in the future, but the basic ingredients of a great industrial development—coal, or oil, and iron—are lacking. The agricultural products in the 1950s were cotton, tobacco, manioc, corn, sugar cane, rice, peanuts, yerba mate, citrus fruits, melons, sweet potatoes, beans and garden vegetables, pineapples, bananas, and other fruits. Lumbering was also important. In addition to the quebracho tree, which furnished tannin, there were some types of trees and grasses from which oils could be profitably extracted, including oil of petitgrain, tung, castor, and coconut oils. Cattle raising was an important industry, providing meat, meat extract, which was largely exported, and hides.

The people are largely a mixture of Spanish and Indian with the Indian (Guaraní) predominating. The number of pure Indians and of pure Europeans is not large. There are some Spaniards, a few Italians, Germans, Englishmen, Slays, and others, besides the Mennonites, who are of Dutch and German ethnic origin.

The Spanish impact on Paraguay goes back to 1537 with the founding of the first settlement, Asuncion. During most of the colonial period Asuncion, the capital of Paraguay, served as the center from which the La Plata section of South America was administered. Since obtaining its independence from Spain in the second decade of the 19th century, Paraguay has had a checkered history. Three dictators dominated the political scene down to 1870, and since that time uprisings and revolutions of one kind or another frequently plagued the country. Disastrous foreign wars also contributed to the country's backwardness. One of these was the Chaco War in the 1930's, in which the Mennonites, by settling on territory in dispute between Paraguay and Bolivia, played an unintentional part.

Spain contributed her religious and cultural pattern to Paraguay. The great majority of the people in the 1950s were Roman Catholic, although the attachment on the part of many was no more than nominal. Religious and moral standards were quite low. The number of Protestants in Paraguay was not large, the Mennonites constituting the largest Protestant body. The educational level was also quite low, although the authorities were making heroic efforts to raise it.

It was into this environment that the Mennonites began to come in the 1920's. Some of the most conservative groups of the Mennonites from Western Canada, who had come from Russia in the 1870's, were the first to become interested in Paraguay. They prospered fairly well in Canada until World War I, when the Canadian government began to more fully nationalize its various ethnic elements. This effort included the passing of a law eliminating private elementary schools and, in the public schools, compelling the use of English and forbidding the teaching of religion. These conservative groups of German-speaking Mennonites considered this a serious curtailment of privileges promised them when they came to Canada, and they began to look for new countries to which they might emigrate. The Old Colony Mennonites in 1919-1920 investigated several countries in South America, but then decided to move to Mexico. Another conservative group composed of Sommerfelder, Chortitzer, and a few Bergthaler Mennonites then became interested in Paraguay. Oral promises of special privileges already made to the Old Colony group were now renewed and passed as a law in 1921. This famous and generous privilegium provided, among other things, that Mennonites and their descendants would have the right to practice their religion and to worship with complete and unrestricted liberty, to make simple affirmations in courts of justice, and to be exempt from obligatory military service, combatant and noncombatant, in time of peace and war. They were also given the right to maintain and administer their own schools and to teach their religion and their German language without restriction.

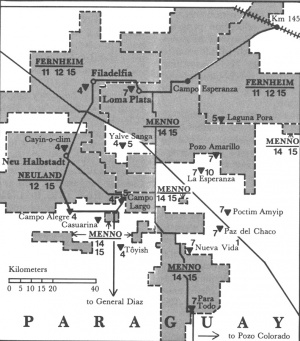

Because of the depression of 1921 and the difficulty of selling their land at satisfactory prices the group which became Menno Colony did not get started on their way to Paraguay until near the end of 1926. With those who came in 1927, a total of 1,778 souls arrived at the river port of Puerto Casado. Since their land, lying slightly more than 100 miles (160 km) west, bought from the specially formed Corporación Paraguaya, was not ready for settlement, these people were bitterly disappointed in their forced prolonged stay in and near Puerto Casado. In addition, tragedy struck in the form of typhoid and other diseases, taking a toll of over 200 lives. Over 300 disillusioned migrants returned to Canada. But the main body was finally able to settle on its own land in 1928 and the discontent was largely dissipated. Very few persons left this colony after actual settlement on the land. They settled in villages (fourteen in 1928), as had been the practice of their forefathers in Russia. This group, known as Menno Colony, was the first Mennonite settlement in South America and the most stable.

The names of a few non-Mennonites who helped in this venture should be mentioned. General Samuel McRoberts, a New York banker, was contacted by the Mennonites and his interest and help enlisted in the cause. He, together with another banker as a partner, Edward B. Robinette, helped the Mennonites dispose of their holdings in Canada and helped them, through Corporación Paraguaya, buy and settle on their lands in Paraguay. McRoberts hired a Norwegian, Fred Engen, to help him explore and select an area in which the Mennonites might be interested. It was Engen who suggested the Chaco area.

The next group of Mennonites who came to Paraguay were refugees from Russia. During the 1920s, as a result of the Communist revolution in Russia, some 21,000 Mennonites came to the United States and Canada, largely the latter. Other thousands, thinking the Communist storm would blow over, and lulled by the partial retreat from Communism under the New Economic Policy (NEP) following 1921, were less inclined to leave at that time. In 1929, after new and more persistent efforts to put Communism with its antireligious aspects into effect, the Mennonites realized too late that the emigration doors were pretty tightly closed. Nevertheless, out of the 13,000-15,000 said to have started for Moscow with the hope of escape, slightly less than 6,000 (including some non-Mennonites) were finally, on 25 November 1929, permitted to leave for Germany, which gave them temporary asylum.

Penniless, these refugees needed help and received it from European and North American Mennonites and also from non-Mennonite Germans. Where these people should be settled permanently was a problem. Germany seemed at that time unable to keep them and doors to the United States and Canada, where they preferred to go, were now closed for the great majority. The Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) came to their aid and after studying the matter as thoroughly as was possible in the short time at its disposal recommended Paraguay. Brazil was also open and a minority decided to migrate to that country. But Paraguay was one of the very few countries which promised them the freedom they desired and which at the same time was willing to receive the aged, ill, and crippled along with the others. Harold S. Bender was sent as the MCC representative to Germany in January 1930, to help arrange and organize the movement to Paraguay. In Paraguay the MCC arranged for the purchase of land from Corporación Paraguaya next to Menno Colony. In 1930-1932 a total of slightly more than 2,000 persons from Russia migrated to the Paraguayan Chaco and established Fernheim Colony. This number included 50 Mennonites who came from Poland and 367 who came from Russia by way of Harbin, China. In the Fernheim migration three Mennonite branches were represented—Mennonites (in the 1950s General Conference Mennonite), Mennonite Brethren, and a small number of Allianz Gemeinde (corresponding to the Evangelical Mennonite Brethren).

Other than the small temporary settlement at Horqueta near Concepción, the third Mennonite settlement to be established in Paraguay was Friesland. This colony was founded by Fernheim settlers who were dissatisfied with the hot and dry Chaco and many of whom were also opposed to the colony cooperative. After investigating several places in eastern Paraguay the group decided to settle about 45 km east of the Paraguay River port of Rosario, or slightly over 160 km northeast of Asunción. The exodus from Fernheim occurred during the winter months of 1937, and by September 748 persons had settled and established Friesland Colony. The pattern of the new settlement was similar to that of Fernheim—settlement in villages; it also had the same religious organizations (General Conference Mennonite and Mennonite Brethren) except that very few families of the Allianz Gemeinde had migrated. In time even a business cooperative, which had been so disliked in Fernheim, was formed, but membership was made voluntary. The exodus from Fernheim weakened that colony and caused some bitterness. The Mennonite Central Committee discouraged the movement and gave no assistance to the new settlement until some years later. Economically, progress in the Friesland settlement was disappointing as in the other colonies.

In both Fernheim and Friesland considerable dissatisfaction with Paraguay manifested itself during the 1930s and early 1940s and not a little pro-German and pro-Nazi sympathy developed, especially in Friesland, but also in Fernheim; none, however, in Menno. The percentage of persons with pro-German sympathies was higher in Friesland, but the turmoil and problems resulting from the sympathy was greater in Fernheim. For a while there was more talk of returning to Europe than of further Mennonite migrations to Paraguay, and some actually returned to Germany during the war. After the war, however, this feeling disappeared, and there were actually new Mennonite migrations to Paraguay.

In 1929, when the few thousand Mennonites were able to leave Russia, a larger number was forced to remain behind. During the course of the invasion and occupation of South Russia by the German army in 1941-1943, additional thousands of Mennonites fled from Russia to Western Europe. Though many were forced to return to Russia, about 4,500 persons immigrated to Paraguay in 1947-1948, besides the 162 persons who came with the group but remained in Buenos Aires. This new immigration to Paraguay was again due to the fact that the doors to other satisfactory countries were closed at this time. The International Refugee Relief Organization (IRO) gave the MCC generous assistance in moving these refugees to Paraguay, and the colonies of Fernheim, Menno, and Friesland helped the MCC to get the new immigrants settled on the land. A few of these people settled in Asunción or in the colonies already established, but the majority organized two new colonies. The new Chaco colony of Neuland, located a few miles south of Fernheim, had a population of 2,389 in 1948, and the new colony of Volendam, a few miles north of Rosario on the Paraguay River, had 1,172 inhabitants in that year. The movement to these colonies was somewhat retarded by the Paraguayan revolution of 1947, some groups having been forced to wait several months in Buenos Aires or Asunción.

The most recent Mennonite settlements in Paraguay were founded in 1948 by fellow believers of Menno Colony—Sommerfelder and Chortitzer Mennonites from southern Manitoba, and a smaller contingent from Saskatchewan. Migration conscious ever since the founding of Menno Colony and fearing the impact of continued secularization on their way of life, they finally decided to emigrate. Not satisfied with the Chaco, where their brethren had located, they founded two colonies, Sommerfeld and Bergthal, in southeastern Paraguay between Villarica and the Brazilian border. About 1700 persons emigrated, but because of disillusionment with the primitive and difficult situation they found some 600 returned to Canada in 1948-1950.

The Hutterian Brethren, distantly related to the Mennonites, in 1941 also formed a settlement in eastern Paraguay next to the Mennonite settlement of Friesland. Of a heterogeneous European background, the group numbered 350 in 1941 and grew to 604 by 1950. This Bruderhof was called Primavera. In 1961 they sold their land to Friesland, and most emigrated to the United States.

As to the future of the Mennonites in Paraguay, no one, of course, can speak with certainty. Some groups were better satisfied and more stable than others. Menno Colony, as noted, was the most stable. Fernheim perhaps comes next, although a few were still leaving. In the newer colonies of Neuland and Volendam there was considerable dissatisfaction and quite a few have left—and were still leaving—mostly for Canada, where many had relatives. The economic and cultural backwardness of Paraguay together with its political instability contributed to this unrest. Climate, insects, transportation difficulties, and lack of adequate markets also made the struggle hard. On the other hand, many appreciated greatly the freedom they had and were willing to continue in hope that most of the discouraging conditions would improve. In this they were probably correct. For progress has been made, and more was likely to be made in the future. -- Willard H. Smith

The Mennonites in the Mennonite colonies of Paraguay were distributed as follows:

| Colony | 1940 | 1950 | 1956 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menno | 2,020 | 3,169 | 4,265 |

| Fernheim | 1,512 | 2,339 | 2,524 |

| Neuland | ____ | 2,497 | 2,162 |

| Friesland | 822 | 986 | 969 |

| Volendam | ____ | 1,810 | 1,317 |

| Bergthal | ____ | 574 | 6391 |

| Sommerfeld | ____ | 626 | 6441 |

| Asunción | ? | ? | 1702 |

| Total | 4,354 | 12,001 | ca. 13,040 |

1. As of 1953.

2. Variable figure because of shifting population.

1990 Article

The time after the Paraguayan war against Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina (1864-1870), in which most of the men of Paraguay were killed and in which it suffered great territorial losses, was a time of political chaos. From 1860-1954, a period of 94 years, Paraguay had 40 different presidents, many of whom were removed by strikes or revolution. The result was a very slow national recovery, hindered also by the bloodletting of the Chaco War (1932-35).

In 1954 General Alfredo Stroessner, son of a German immigrant father and Paraguayan mother, became president. With the support of the Colorado party he has governed Paraguay to the present day (1987). Paraguay's recovery during this time was rapid, not only in its infrastructure, but also in its external political relationships. This also affected the Chaco region, which was won for Paraguay through the Chaco War and which was increasingly integrated into the Paraguayan economy.

While the population of Paraguay grew from 1 million (1930) to 3.5 million (1987) to 6.2 million (2004), this still was only fifteen inhabitants per square kilometer. Immigration remained low though the immigration laws were very favorable. The privileges granted to the Mennonites in 1921, confirmed in law No. 514, remained intact. This led to further immigration of Mennonites, especially from Mexico after 1969. Total Mennonite membership in Paraguay was estimated in 1987 at 14,000. Though they enjoyed special privileges, Mennonites were still well received in Paraguay, particularly by the government, due in large part to the strength of their economic contribution, particularly their cooperative approach to economics.

Several North American Mennonite-related groups have attempted migrations to Paraguay during the last 30 years, including Old Order Amish (1967-1978) at Fernheim Colony and Beachy Amish Mennonites (1967- ) at Luz y Esperanza Colony. -- Peter P. Klassen

See also: Agua Azul Colony; Bergthal Colony; Bergthal Mennonites; Convención de las Iglesias Evangélicas Chulupi; Convención de las Iglesias Evangélicas de los Hermanos Lenguas; Convención Evangélica Menonita Indiginista; Evangelical Mennonite Conference (Kleine Gemeinde); Fernheim Colony; Friesland Colony; Konferenz der Mennonitischen Brüdergemeinden von Paraguay; Licht den Indianern; Luz y Esperanza Colony; Manitoba Colony, Paraguay; Menno Colony; Mennonitisches Missionskomitee für Paraguay; [La] Montana Colony; Neuland Colony; Old Colony Mennonites; Reinfeld Colony; Rio Corrientes Colony; Rio Verde Colony; Santa Clara Colony; Sommerfeld Colony, Paraguay; Sommerfeld Mennonites; Tres Palmas Colony; Vermittlungskomitee; Volendam Colony.

2013 Update

In 2012 the following Anabaptist groups were active in Paraguay:

| Denominations | Congregations in 2000 | Membership in 2000 | Congregations in 2003 | Membership in 2003 | Congregations in 2006 | Membership in 2006 | Congregations in 2009 | Membership in 2009 | Congregations in 2012 | Members in 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altkolonier Mennonitengemeinde (Colonia Manitoba) | 1 | 239 | 1 | 257 | 1 | 287 | 1 | 325 | 3 | 375 |

| Altkolonier Mennonitengemeinde (Colonia Nueva Durango) | 1 | 600 | 2 | 650 | 2 | 750 | 3 | 687 | 3 | 756 |

| Altkolonier Mennonitengemeinde (Colonia Rio Verde) | 1,263 | 6 | 1,263 | 6 | 1,521 | 6 | 1,521 | 6 | 1,436 | |

| Amish Mennonites | 2 | 41 | ||||||||

| Bergthaler Mennonitengemeinde (Paraguay) | 1 | 867 | 1 | 913 | 1 | 943 | 5 | 980 | 5 | 1,078 |

| Confraternidad Evangélica Menonita del Paraguay (CEMP) | 13 | 325 | 14 | 300 | ||||||

| Conservative (Plain) Mennonites | 5 | 192 | ||||||||

| Convención Evangélica de Iglesias Paraguayas de los Hermanos Menonitas | 60 | 2,950 | 69 | 3,052 | 76 | 3,500 | 53 | 3,150 | 65 | 3,500 |

| Convención Evangélica Hermanos Menonitas Enlhet | 7 | 2,125 | 7 | 2,300 | ||||||

| Convención Evangélica Mennonita Lengua | 7 | 1,825 | 7 | 2,084 | 7 | 2,070 | ||||

| Convención Evangélica Menonita Paraguaya | 27 | 920 | 27 | 1,203 | 32 | 1,450 | 47 | 1,707 | 47 | 2,182 |

| Convención Iglesias Evangélicas Hermanos Menonitas Nivaclé | 8 | 1,922 | 8 | 2,260 | 9 | 2,260 | 10 | 3,561 | 11 | 2,250 |

| Convención Iglesias Evangélicas Unidas - Enlhet Paraguay / Convención de las Iglesias Evangélicas Unidas Enlhet Paraguay Chaco Central | 14 | 4,600 | 14 | 4,032 | 15 | 4,049 | 15 | 4,162 | 16 | 4,250 |

| Evangelische Mennoniten Gemeinde | 1 | 201 | 1 | 275 | 1 | 339 | 1 | 372 | 1 | 416 |

| Evangelische Mennonitengemeinde | 3 | 105 | 3 | 118 | 2 | 103 | 2 | 143 | 1 | 48 |

| Evangelische Mennonitengemeinde Neues Leben | 1 | 46 | ||||||||

| Evangelische Mennonitengemeinde Tres Palmas | 1 | 92 | ||||||||

| Evangelische Mennonitische Bruderschaft | 1 | 450 | 1 | 455 | 1 | 750 | 1 | 500 | ||

| Hermandad Cristiana de Paraguay / Beachy Amish Mennonite Fellowship | 3 | 78 | 2 | 87 | 2 | 87 | 2 | 99 | 2 | 93 |

| Iglesia Hermandad Evangélica Mennonita - Filadelfia | 7 | 908 | ||||||||

| Iglesias Evangélicas Hermanos Menonitas Guaraní Ñandeva / Convención Evangélica Hermanos Menonitas Guaraní Ñandeva | 7 | 550 | 10 | 620 | ||||||

| Iglesias Guaraní Ñandeva | 8 | 550 | 8 | 550 | 8 | 550 | ||||

| Independent & Unaffiliated | 5 | 190 | 5 | 180 | ||||||

| Mennonite Christian Brotherhood (Agua Azul) | 1 | 30 | 1 | 38 | ||||||

| Mennoniten Evangeliums Kirche | 1 | 37 | ||||||||

| Misión Evangélica Menonita | 13 | 192 | 14 | 210 | 16 | 335 | ||||

| Reinfelder Mennoniten Gemeinde (Colonia Reinfeld) | 1 | 66 | 1 | 66 | 1 | 66 | 1 | 80 | 1 | 80 |

| Sommerfelder Mennonitengemeinde (Colonia Sommerfeld) | 2 | 1,182 | 2 | 1,220 | 6 | 1,032 | 7 | 1,165 | ||

| Sommerfelder Mennonitengemeinden (Colonia Santa Clara) | 1 | 137 | 1 | 144 | 1 | 130 | 1 | 124 | 1 | 137 |

| Vereinigung der Mennoniten Brüdergemeinden Paraguays /

Asociación Caritativa de los Hermanos Menonitas del Paraguay | 7 | 1,593 | 7 | 1,623 | 7 | 1,623 | 26 | 3,195 | 30 | 3,112 |

| Vereinigung der Mennonitengemeinden von Paraguay / Convención de los Pastores de las Iglesias Mennonitas del Paraguay | 19 | 7,350 | 19 | 7,231 | 20 | 7,238 | 20 | 7,399 | 21 | 7,837 |

| Total | 177 | 25,938 | 195 | 27,693 | 215 | 29,461 | 232 | 32,217 | 268 | 33,251 |

Bibliography

Dueck, David. To Build a Homeland: Home in a Strange Land. Winnipeg: Mennonite Historical Society of Canada, 1981.

Duerksen, Hans. Fernheim 1930-1980: 50 Jahre Kolonie Fernheim: Eine Beitrag in der Entwicklung Paraguays. Filadelfia, 1980.

Fretz, J. W. Immigrant Group Settlements in Paraguay. North Newton, 1962.

Fretz, J. Winfield. Pilgrims in Paraguay: the story of Mennonite colonization in South America. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1953.

Friesen, Martin W. Kanadische Mennoniten Bezwingen eine Wildnis: 50 Jahre Kolonie Menno--erste mennonitische Ansiedlung in Südamerika. Kolonie Menno, 1977.

Friesen, Martin W. Neue Heimat in der Chacowildnis. Alton, MB: D. W. Friesen, and Menno Colony: Chortitzer Komitee, 1987.

Funk, Abram. 25 Jahre Volendam 1947-1972. Volendam: Komitee für kirchliche Angelegenheiten, 1972.

Hack, H. Die Kolonisation der Mennoniten im Paraguayischen Chaco. Amsterdam: Kon. Tropeninstitut.

Handbook of Information, General Conference Mennonite Church. Newton, KS (1988): 39-40, 92.

Horsch, James E., ed. Mennonite Yearbook and Directory. Scottdale: Mennonite Publishing House (1986-87): 160.

Klassen, Peter P. Immer kreisen die Geier. Filadelfia, 1983.

Klassen, Peter P. Kaputi Mennonita: Eine friedliche Begegnung im Chacokrieg. Filadelfia, Paraguay, 1975.

Klassen, Peter P. Die Mennoniten In Paraguay: Reich Gottes und Reich dieser Welt. Bolanden-Weiherhof: Mennonitischer Geschichtsverein, 1988.

Krause, Annemarie E. "Mennonite Settlement in the Paraguayan Chaco." PhD diss., U. of Chicago, 1952.

Kraybill, Paul N., ed. Mennonite World Handbook. Lombard, IL: Mennonite World Conference, 1978: 242-60.

Krier, Herbet. Tapferes Paraguay, 4th ed. Tübingen, 1982.

Kroeker, P. J. "Lenguas and Mennonites: A Study of Cultural Change in the Paraguayan Chaco, 1928-1970." Thesis, Wichita State University 1970.

Lewis, Paul H. Paraguay under Stroessner. Chapel Hill, NC: U. of North Carolina, 1980.

Luthy, David. Amish Settlements Across America. Aylmer, ON: Pathway, 1985: 2.

Mennoblatt (1930- ).

Mennonite Brethren General Conference Yearbook (1981): 117-18.

Mennonite World Conference. "2000 Caribbean, Central & South America Mennonite & Brethren in Christ Churches." Web. 11 November 2010. http://www.mwc-cmm.org/Directory/2000carcsam.html.

Mennonite World Conference. "2003 Caribbean, Central & South America Mennonite & Brethren in Christ Churches." Web. 11 November 2010. http://www.mwc-cmm.org/Directory/2003carcsam.html.

Mennonite World Conference. "Mennonite and Brethren in Christ Churches Worldwide, 2009: Latin America & The Caribbean." 2010. Web. 28 October 2010. http://www.mwc-cmm.org/en15/files/Members 2009/Latin America & the Caribbean Summary.doc.

Mennonite World Conference. "MWC - 2006 Caribbean, Central and South American Mennonite & Brethren in Christ Churches." Web. 20 October 2008. http://www.mwc-cmm.org/en/PDF-PPT/2006carcsam.pdf <span class="link-external"><span class="link-external"></span></span>.

Mennonite World Conference. World Directory = Directorio mundial = Répertoire mondial 2012: Mennonite, Brethren in Christ and Related Churches = Iglesias Menonitas, de los Hermanos en Cristo y afines = Églises Mennonites, Frères en Christ et Apparentées. Kitchener, ON: Mennonite World Conference, 2012: 24-26.

Mennonite World Handbook Supplement. Strasbourg, France, and Lombard, IL: Mennonite World Conference, 1984: 93-101.

Mennonitisches Jahrbuch (1984): 156-58.

Plett, Rudolf. Presencia menonita en el Paraguay. Asunción: Instituto Biblico Asunción, 1979.

Quiring, Walter. Rußlanddeutsche suchen eine Heimat. Karlsruhe: Heinrich Schneider Verlag, 1938.

Ratzlaff, Gerhard. Auf den Spuren der Vaeter: Eine Jubiläumsschrift der Kolonie Friesland in Ostparaguay 1937-1987. Kolonie Friesland, Paraguay: G. Ratzlaff, 1987.

Ratzlaff, Gerhard. Deutsches Jahrbuch für 1988: Geschichte, Kultur, Unterhaltung. Asunción, Paraguay, 1988.

Ratzlaff, Gerhard. Eine Leib-viele Glieder: Die mennonitischen Gemeinden in Paraguay. Asuncion: Gemeindekomitee, 2001.

Ratzlaff, Gerhard. One Body, Many Parts: The Mennonite Churches in Paraguay. Trans. Jake K. Balzer. Paraguay: G. Ratzlaff, 2008.

Redekop, Calvin. Strangers Become Neighbors: Mennonite and Indigenous Relations in the Paraguayan Chaco. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1980.

Regehr, Walter. 25 Jahre Kolonie Neuland Chaco--Paraguay 1947-1972. Neuland: Kolonieverwaltung, 1972.

Regehr, Walter. "Die lebensraumliche Situation der Indianer im paraguayischen Chaco." Dissertation, U. of Basel, 1979.

Smith, Willard and Verna. Paraguayan Interlude: observations and impressions. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1950.

Stahl, Wilmar. Guided Social Change in the Paraguayan Chaco. Filadelfia, 1973.

Stoesz, Edgar. Like a Mustard Seed: Mennonites in Paraguay. Scottdale, PA, Waterloo, ON: Herald Press, 2008.

Stoesz, Edgar and Muriel T. Stackley. Garden in the Wilderness: Mennonite Communities in the Paraguayan Chaco, 1927-1997. Winnipeg, MB: CMBC Publications, 1999.

Warkentin, Abe. Compiler. Strangers and Pilgrims. Steinbach, MB: Mennonitische Post, 1987.

Warren, H. G. Paraguay and the Triple Alliance. Austin: U. of Texas Press, 1978.

| Author(s) | Willard H. Smith |

|---|---|

| Peter P. Klassen | |

| Date Published | May 2013 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Smith, Willard H. and Peter P. Klassen. "Paraguay." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. May 2013. Web. 2 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Paraguay&oldid=76840.

APA style

Smith, Willard H. and Peter P. Klassen. (May 2013). Paraguay. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 2 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Paraguay&oldid=76840.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 4, pp. 117-119; vol. 5, pp. 672-674. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.