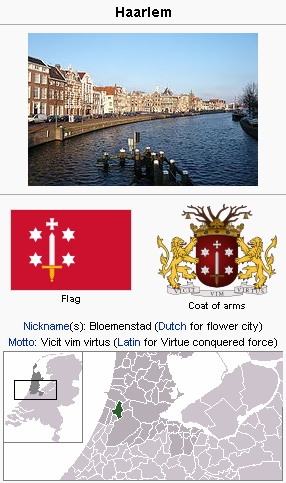

Haarlem (Noord-Holland, Netherlands)

Introduction

Haarlem, Netherlands is a city (population of 166,000 in 1956, three per cent of which was Mennonite; population of 147,000 in 2008) since 1345. It became the capital of the province of North Holland in the 19th century. A considerable number of industries have been located here, especially the famous printing house "Enschede." The city also has had several Mennonite publishers: N. V. Erven Bohn and H. D. Tjeenk Willink en Zoons Uitgevers Mij N.V. Haarlem is also the center of the Dutch flower bulb culture, which is centuries old, and in whose history we also find Mennonites such as Voorhelm and Schneevoogt. The city has experienced times of growth and decline which have influenced the life of the various Mennonite congregations located here, of which the two surviving in 1784, the Flemish (Klein Heiligland) and the Waterlander (Peuzelaarsteeg), merged to form the United Mennonite Church. In 1671 there were 1,868 members in the Heiligland congregation. If the members of the Waterlander and other smaller congregations are included, the Mennonite proportion of the city's population at that time would certainly have been 15-20 per cent. In 1640 the Mennonite population was estimated at nearly 5,000 baptized members. The city was known as "the Mennonite Haarlem" because there were many prominent and influential citizens among them.

History

About 1530 there were already Anabaptists in Haarlem. Court trials of Anabaptists took place here repeatedly about that time, although these brethren and sisters came from other sections of the province of Holland. It is clear also that among those on trial were some who either played a part in the Münster affair or were involved in it. Jan Matthijs himself was from Haarlem. A large number of Anabaptists were arrested in March 1534 at Spaarndam north of Haarlem, victims of the unscrupulous Jan van Leyden. Anabaptists were to be found in the whole district around Haarlem, in Kennemerland and Waterland. After the Münsterite affair it is reported that a congregation was formed in the city of Haarlem, although we have no direct evidence of this. It is known that the city authorities of Haarlem in the early years did not always obey the instructions of the national government; later this was changed. On 26 April 1557 the bookseller Joriaen Simonsz was first strangled and then burned at the stake, as was also Clement Dirksz, while a fellow prisoner, Mary Joris, likewise sentenced, then in childbirth. Before the trial of these first two martyrs there was a meeting in the Schouts Street in which a certain Bouwen Lubbertsz preached "without fear or fright." In his last will and testament to his son Simon, Joriaen Simonsz tells his son not to have any fellowship with "Lutherans, Zwinglians or such others," but "search out a little flock whose whole rule of life agrees with the commandments of God. They also have preachers." From this and from the fact that Leenaert Bouwens baptized 11 persons at Haarlem in 1551-1578 it is clear that there was a church here by 1560 and possibly earlier. To what extent this congregation or its ministers played a part in the meeting of 1557 at Harlingen is not known. However, from the connection with Leenaert Bouwens we should assume that the strict party had the upper hand.

In the meantime the Anabaptists of Haarlem were persecuted. The sheriff Jacob Foppens, assisted by a spy called Aagt, was able to arrest several members, particularly in 1570. Among these were Anneken Ogiers, daughter of Jan Ogiersz, wife of the potter Adriaen Boogaert, who was sentenced to death by drowning on 17 June. She had been baptized in 1557 at Amsterdam. Other victims were Barber Jans, Allert Jansz, Andries N., Adriaen Pietersz, and Barber Joosten. Soon thereafter (1571) Alba's Spanish troops occupied the city. Then came the rebellion of 1572 when the city took the side of the Prince of Orange, followed by the siege in 1573, which ended with surrender to Don Frederik. It was only after the Treaty of Veere in 1577, which granted toleration to both Roman Catholics and Reformed, that Haarlem again could open its gates to Protestant refugees from Flanders, among whom were many Mennonites. This number increased after the fall of Antwerp in 1585. One of these refugees was the well-known poet and painter Karel van Mander, author of the Schilderboeck and two books of poems, De Gulden Harpe and Bethlehem. He lived in Haarlem 1583-1603. Among other Mennonites of this time should be named the families of de la Faille, Anselmus, Hartsen, Hoofman, Coppenol, Verkruissen, Verbrugghe, Messchaert, Apostool, Boeckenhove (Boekenoogen), and Bodisco. Refugees from other sections and other countries also sought and found permanent refuge in Haarlem, among whom were the Willinks from Winterswijk, and Thomas Teyler from England, ancestor of the well-known Pieter Teyler van der Hülst. One should also name here another Fleming, Hans de Ries, who also must have lived for a time in Haarlem. Whereas he was a man of toleration, the opposite was the case with the Fleming Hans Doornaert, a weaver and formerly a preacher in the congregation at Ghent. He and Jacob Jansz Schedemaker got into a dispute over the question of prayer (1587), a matter in which Dirk Volkertsz Coornhert, the secretary of the city, also took part.

But now we have come to the time of the many congregations. In addition to the Flemish congregation there were a Waterlander, a Frisian, and a High German. Each has its own separate history, although little is known of the earlier years. The Flemish and the Frisians seemingly developed into separate congregations about 1567. The Waterlanders, however, had probably been in existence ten years earlier as followers of Schedemaker. The High Germans formed a separate congregation on the basis of their national origin. The Flemish had undoubtedly the largest congregation in Haarlem. The writer of the letter of 1740 to Pastor Martinus Schagen (Doopsgezinde Bijdragen, 1863) confirms this. The letter also indicated that since 1589 the Old Flemish, also called "Huiskopers" the, had their own congregation at "De Vier Heemskinderen" on the Helmbreekerssteeg near Spaarne. The Young Flemish who were more moderate, whose minister was the well-known Jacques Outerman, by 1614 had a large church building in the Groenendaalsteeg near the Smalle Gracht.

The Old Flemish had as their preachers Vincent de Hont, Phillips van Casele, and later Lucas Philips. The first and the last of these fell into a quarrel ca. 1620 concerning the question of whether a bridegroom who had intimate relations with his bride before the wedding day was to be subject to punishment or not. Vincent was strict, and so a division came about in the Haarlem congregation between the Vincent de Hont group and the Lucas Philips group or "Borstentasters". The latter continued to meet in the Helmbreekerssteeg, while the followers of Vincent met in the Oude Gracht near the Raaks. The two congregations continued to be irreconcilable even though they were declining. The Lucas Philips group died out about 1700. The Vincent de Hont group or Old Flemish held out longer. In the 18th century they sought contact with the Danzig Mennonites and also with the congregations at Blokzijl and Sappemeer. Eduard Simons Toens, Pieter Boudewijns, and Abraham Tieleman were their last ministers. Many of the members withdrew to join either the Heiligland congregation (the continuation of the Young Flemish) or the Waterlander group at Peuzelaarsteeg. In 1773 the last members joined their fellow believers at Amsterdam. Separate from the latter group, but with much in common, was a congregation of the Groningen Old Flemish, whose ministers were Evert and Pieter Mabé, and which met in the Lange Margarethastraat. This congregation ceased to exist after the death of Pieter Mabé in 1781.

The Young Flemish in 1604 bought a building in the Klein Heiligland called the "Olyblock." In 1626 a church was built (enlarged in 1650) which served until 1795. This congregation was originally the most important one in Haarlem, and was called commonly the "Block" or "Flemish Block." In 1671 the congregation had 1,868 baptized members. Before following its history, however, it is necessary to look at the course of affairs in the High German, Frisian, and Waterlander congregations. In 1602 these groups united; that is, the Mild Frisians joined the other groups. Their meetinghouse stood close by the Gasthuisvest between the Grote Houtstraat and Heiligland with an entrance on the Houtstraat. Leenaert Clock, the preacher in the High German congregation, had promoted the union. But he and Claes Wouters Cops in 1611 separated from the group, and with their followers formed the United High German and Frisian congregation. The other group remained for a time under the name United Congregation of High Germans, Frisians, and Waterlanders. They had by far the majority and kept the old name. From 1611 to 1617 the two groups had to use the meetinghouse alternately, but in the latter year a new meetinghouse was built right behind the old one to serve the Waterlander group, with its entrance at the Klein Heiligland, so that after 15 years there was again a complete division. This new group was the one which grew in numbers and in 1683 built the church in the Peuzelaarsteeg. In 1617 it had 290 members whose names are known. The Leenaert Clock group continued independently until 1638, when it united with the Flemish congregation (Block) on the basis of the Olive Branch Confession. Among the preachers of the High Germans and Frisians were Isaac Snep and Coenraad van Vollenhoven. In the Flemish congregation was Pieter Grijspeert. In addition to these "united" congregations and the previously named congregations of Vincent de Hont and Lucas Philips there was a congregation of the Little Frisians which met in the Zijlkerk, and a High German congregation which met in the Wijnberg in the Barrevoetestrajt, where it had a meetinghouse. The former died out, while the latter also united with the "Flemish Block" congregation in 1651-1652.

We now turn our attention to the two largest congregations. The Waterlander congregation had a sturdy growth, but the Flemish Heiligland congregation did not. The tensions and the strife between the Amsterdam preachers Galenus and Apostool, the War of the Lambs (Lammerenkrijg), had led to a similar division in Haarlem. The cause of this was the fact that ten Flemish members had taken communion in the Waterlander congregation. When they were called to account by the strict party of Isaac Snep an uproarious tumult developed in which the followers of Snep shouted loudly and jumped down from the balconies to the main floor. The quarrels continued until 1655. Already quite a number had left the congregation to join the Waterlander congregation, among them the preacher Hendrik van Thepenbroek. Due to the intervention of the city authorities a division came about. The party of Isaac Snep and Pieter Marcus had 1,360 supporters, while that of Coenraad van Vollenhoven had 508. Once again the two groups had to hold their services alternately in the same building. Van Vollenhoven considered the grounds for the division to be insufficient, but Snep and his party, strengthened by ministers of other congregations, demanded their rights in a petition of April 1669 to the authorities. After vain attempts at a reconciliation the city officials on 18 August 1671 ordered a partition wall built into the church. The larger northern part of the building was given to Snep and his followers, the southern part to van Vollenhoven. There was also a division of the property. In 1672 the Waterlander congregation united with the van Vollenhoven group, so that their part of the meetinghouse became too small. Plans for a new church building could not be carried out until 1683 as reported above.

A new quarrel divided the Flemish congregation, where Thomas Snep held the scepter. His co-minister Jan Evertsz had married as his second wife a woman who had many debts. He was now accused of being a "bankrupter." Again the authorities intervened, and in 1681 Evertsz and his group left to hold their meetings in the "Glashuys" in the Bakenessergracht. In 1684 this group, which had 728 members, built a new church in the Kruisstraat. The group of Thomas Snep, which had 382 members, continued to meet in the "Flemish Block" meetinghouse, which was now much too large. Again the necessary division of property caused much difficulty, but finally the orphanage and the Zuiderhofje were given to the Kruisstraat congregation. Attempts at a reunion made by the Waterlanders in 1688 and even by the Flemish Heiligland congregation in 1689 were rejected. Finally in 1747 the congregation was dissolved and the members joined the Heiligland congregation. Now comes the time when the smallest congregations died out, and finally in 1784 the two largest congregations united on the basis of the Acte van Vereeniging. After more than two centuries of divisions with the resulting large loss of members, peace had returned. In Haarlem for a longer or shorter time there had been 20 different Mennonite congregations, with 14 different meetinghouses.

Originally all the congregations had lay preachers, whose number is too great to be listed here. The first salaried preacher was Pieter Schrijver, who came to the Flemish congregation from Hoorn in 1706. In the Waterlander congregation it was Nicolaas Verlaan, who came from Rotterdam in 1729. It was natural that after the establishment of the seminary the Haarlem congregations secured their preachers from this training school. In addition to the regular Sunday services and the catechetical instruction of the youth, the deacons took care of the needy members and of the ordinary education of their children. Each of the two large congregations originally had an orphanage, as well as one of the almshouses which belonged to the various congregations. In 1782 a separate house was built, called the "Armen-" or "Bestedelingen-Huis" (poorhouse) to provide for the old, poor, and infirm members who had been taken care of for many years in private families. The building included a school for the children of parents cared for in the house. Soon others asked for admission for their children. Thus arose a separate school in the Groot Heiligland alongside of the poorhouse, which was later called the Kinderhuis. This school, which was rebuilt several times, was closed during World War II and sold to a hospital, and was finally closed in 1952. A second school, built in 1893, was still in use in 1955.

As the older institutions and arrangements became out-of-date others were called into being: district nursing, family care, sending needy members to the brotherhood houses for rest, a new home for the aged (1955), and numerous kinds of youth work. Special mention should be made of the welfare worker.

After 1945 the congregation was served by four preachers; previously there were always three. In 1784, when the two congregations united, the following preachers were serving: Martinus Arkenbout 1757-1790, Klaas van der Horst 1762-1803, Petrus Loosjes Adrz. 1762-1810, Cornelis Loosjes Adrz. 1763-1792, Bernardus Hartman van Groningen 1770-1806. Their successors were Kornelis de Haan 1792- , Matthijs van Geuns Jansz 1792-1823, Abraham de Vries 1803-1838, Sybrand Klazes Sybrandi 1807-1849, Klaas Sybrandi 1838-1871, Sytze Klaas de Waard 1828-1856, Willem Carel Mauve 1839-1863, Hendrik Arend van Gelder 1863-1883, Jeronimo de Vries Gz. 1872-1908, Jacobus Craandijk 1884-1900, Leonard Hesta 1890-1901, H. J. Elhorst 1900-1908, B. P. Plantenga 1901-1927, A. Binnerts Szn. 1907-1932, C. B. Hylkema 1908-1936, J. M. Leendertz 1927-1950, J. G. Frerichs 1932-1946, J. IJntema 1936-1944, S. M. A. Daalder 1945- , C. P. Hoekema 1945- , Miss C. Soutendijk 1946- , J. A. Oosterbaan 1950-54, A. J. Snaayer 1954- .

1950s

The mid-20th century Haarlem congregation was scattered over the several civic areas of Haarlem, Heemstede, Bloemendaal, and Zandvoort, while others were living in the flower bulb districts. The congregation had a meetinghouse in the center of the city built in 1683 with a seating capacity of 700. In 1955 a second church, Noorderkapel, was dedicated. The city of Haarlem itself had 166,000 inhabitants in 1956, not including the suburbs, which had 58,000. Of this total population of 224,000 the Mennonite congregation in 1954 had 3,391 members, 1,337 men and 2,054 women. The congregation was divided into four districts, each district having a preacher and a district committee. Several of the districts were further subdivided. Once a month services were held in Heemstede, Bloemendaal, Haarlem-Noord, and Haarlem-Oost. During the winter there were also district evening meetings in which a topic was discussed. The following services or organizations were sponsored by the church council or the deacons in the 1950s: (1) a "deacon ministry" (diaconie) in which the work is carried on by a welfare worker; (2) a Mennonite nursing service with a district nurse; (3) a Mennonite family aid service with two family social workers; (4) a Mennonite school with eight teachers; (5) a relief fund for lodgings for the aged.

Closely connected with the congregation but autonomously administered were a number of Mennonite institutions and foundations: (1) the Mennonite Orphanage, administered by a board of regents, which had nine children under the direction of a housefather and housemother; (2) the Mennonite rest home "Spaar en Hout," an institution with a capacity of 46 persons founded by the orphanage and administered by its regents; (3) four Mennonite almshouses (hofje) in which 34 elderly sisters of the congregation have their private dwellings — Bruiningshofje (established in 1610), Blokshofje (1634), Zuiderhofje (1640), and Wijnbergshofje (1662); (4) the Mennonite rest home for the aged at Heemstede, property of the Gallenkamp Foundation, with a capacity of 140 persons.

The congregation had nine Sunday schools for children from 9 to 10 years of age, a young people's church for children 11-15, Mennonite Pathfinder groups for boys and girls of 8-17, a Mennonite youth fellowship for young people 15-20 called Elfregi, a Mennonite young people's circle (Kring) for ages 20-30, a study circle for young people, and a study association for men. It had further a circle for members 35-65 years of age, called De Medewerkers, a circle for members 50 years and older, a Mennonite circle for the aged, and 13 sisters' circles. There was also a local unit of the Mennonite Association for the Spread of the Gospel. The ushers (Collectanten) also had their own organization. There was also a Mennonite choir (1894) which was however not a church choir.

The congregation was governed by the "Large Church Council" (Groote Kerkeraad), whose members held office for life. This council was composed of 15 members including the four active ministers and the retired minister living at Haarlem. It met usually three times a year. Current matters were handled by the "Serving Church Council" (Dienende Kerkeraad), consisting of 17 members, which likewise included the four active preachers and the retired preacher. The four active preachers constituted the executive committee of both church councils. Two of these ministers were annually elected as chairman and secretary of the two councils. All matters concerning the support of needy members he in the competence of the board of deacons consisting of 12 members who were also members of the "Serving Council." The preachers could not belong to the board of deacons. The deacons were assisted by a board of deaconesses (five members) and the welfare worker. The board of deacons also controled the current financial affairs of the congregation. The management of the various endowments was handled by autonomous trustees who were members of the Large Church Council.

The congregation is a member of the Algemeene Doopsgezinde Sociëteit, to which it appoints four delegates, and of the North Holland Ring, and also of the Association for the Support of Mennonite Orphans of Needy Congregations. The congregation also had its own monthly periodical which contained reports on the work of the church councils and the various congregational organizations.

Bibliography

The history of the Haarlem congregation has not yet been written. Much material is to be found in the Haarlem congregational and city archives, in Inventaris der Archiefstukken berustende bij de Vereenigde Doopsgezinde Gemeente to Amsterdam. Avast. I and II, and in the Naamlijsten, and in the Doopsgezinde Bijdragen, especially for 1863, pp. 125-164, which contains a letter of 1740 concerning the Mennonites at Haarlem. Material on the orphanages is contained in the memorial volume, De Weeshuizen der Doopsgezinden te Haarlem. 1614-1934. Haarlem, 1934. See also Mennonitisches Lexikon II: 213-215.

| Author(s) | C. B Hylkema |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1956 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Hylkema, C. B. "Haarlem (Noord-Holland, Netherlands)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1956. Web. 22 Nov 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Haarlem_(Noord-Holland,_Netherlands)&oldid=95023.

APA style

Hylkema, C. B. (1956). Haarlem (Noord-Holland, Netherlands). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 22 November 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Haarlem_(Noord-Holland,_Netherlands)&oldid=95023.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, pp. 614-617. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.