Difference between revisions of "Danzig (Poland)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

SamSteiner (talk | contribs) (corrected typo) |

m (Updated information about the Danzig Mennonite Church building.) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

With much Mennonite residence and business activity concentrated in areas immediately outside the city walls, they received repeated setbacks and economic damage with frequent military conflicts during the 16th-18th centuries, which often led to destruction of buildings outside the city walls during sieges of the city. Conflicts included the First Northern War or Seven Years War of the North (1563-1570), the Second Northern War (1655-1660, known as the “Deluge” in Polish memory), the Great Northern War (1700-1721), the War of Polish Succession (1733-1736), and the Napoleonic wars of the early 19th century. | With much Mennonite residence and business activity concentrated in areas immediately outside the city walls, they received repeated setbacks and economic damage with frequent military conflicts during the 16th-18th centuries, which often led to destruction of buildings outside the city walls during sieges of the city. Conflicts included the First Northern War or Seven Years War of the North (1563-1570), the Second Northern War (1655-1660, known as the “Deluge” in Polish memory), the Great Northern War (1700-1721), the War of Polish Succession (1733-1736), and the Napoleonic wars of the early 19th century. | ||

| − | The Flemish church building and alms house were destroyed in the Russian siege of 1734. The Frisian building was remodeled in 1788 and an organ was added. The Flemish also remodeled in 1805-1806 and added an organ against significant opposition. A hand written organ chorale book survives from this time (now at the [[Mennonite Library and Archives (North Newton, Kansas, USA)|Mennonite Library and Archives]], [[Bethel College (North Newton, Kansas, USA)|Bethel College]], [[North Newton (Kansas, USA)|North Newton]], [[Kansas (USA)|Kansas]]). The Frisian building was destroyed during the French siege of 1806 and both groups then merged on 22 May 1808, and used the Flemish building until it too was destroyed in 1813. At the time of the merger the Frisians numbered 166 members and the Flemish around 700. The united congregation dedicated a new building at a new location on 12 September 1819 | + | The Flemish church building and alms house were destroyed in the Russian siege of 1734. The Frisian building was remodeled in 1788 and an organ was added. The Flemish also remodeled in 1805-1806 and added an organ against significant opposition. A hand written organ chorale book survives from this time (now at the [[Mennonite Library and Archives (North Newton, Kansas, USA)|Mennonite Library and Archives]], [[Bethel College (North Newton, Kansas, USA)|Bethel College]], [[North Newton (Kansas, USA)|North Newton]], [[Kansas (USA)|Kansas]]). The Frisian building was destroyed during the French siege of 1806 and both groups then merged on 22 May 1808, and used the Flemish building until it too was destroyed in 1813. At the time of the merger the Frisians numbered 166 members and the Flemish around 700. The united congregation dedicated a new building at a new location on 12 September 1819. |

Despite the relatively low level of persecution of Mennonites in the Danzig region, for most of their centuries of residence there they were second-class inhabitants and were subject to petty harassment. It seems likely that many of the attacks on them were not intended to be seriously carried out but were more along the order of rhetorical displays or political ploys in conflicts that did not have directly to do with the Mennonites. In many cases, these attacks were deflected by bribery; Mennonites paid “donations” or “loans” and were then left alone until the next time that a more powerful party thought they could extract more money. | Despite the relatively low level of persecution of Mennonites in the Danzig region, for most of their centuries of residence there they were second-class inhabitants and were subject to petty harassment. It seems likely that many of the attacks on them were not intended to be seriously carried out but were more along the order of rhetorical displays or political ploys in conflicts that did not have directly to do with the Mennonites. In many cases, these attacks were deflected by bribery; Mennonites paid “donations” or “loans” and were then left alone until the next time that a more powerful party thought they could extract more money. | ||

| Line 89: | Line 89: | ||

The Danzig Mennonite church building survived World War II, in contrast to much of the rest of the city. In 1947 the Polish Communist government granted permission to a Pentecostal congregation to use the building and nearby parsonage. Restoration of the buildings lasted until 1958 because of government delays. In the immediate post-war years, the North American [[Mennonite Central Committee (International)|Mennonite Central Committee]] had a relief program in the area, and the “seagoing cowboy” program brought livestock by ship into the area to aid the revival of agriculture. Both of these programs brought North American Mennonites to Danzig and the Vistula Delta, who visited various Mennonite sites such as the Danzig building. | The Danzig Mennonite church building survived World War II, in contrast to much of the rest of the city. In 1947 the Polish Communist government granted permission to a Pentecostal congregation to use the building and nearby parsonage. Restoration of the buildings lasted until 1958 because of government delays. In the immediate post-war years, the North American [[Mennonite Central Committee (International)|Mennonite Central Committee]] had a relief program in the area, and the “seagoing cowboy” program brought livestock by ship into the area to aid the revival of agriculture. Both of these programs brought North American Mennonites to Danzig and the Vistula Delta, who visited various Mennonite sites such as the Danzig building. | ||

| − | In 1972 the Pentecostal congregation obtained actual legal ownership of the building. In 1989 they took formal ownership of the parsonage and in 2003 the care home. The large, active congregation continued | + | In 1972 the Pentecostal congregation obtained actual legal ownership of the building. In 1989 they took formal ownership of the parsonage and in 2003 the care home. The large, active congregation continued up to 2025 to use the 200-year-old former Mennonite building as one of their meeting places in Gdańsk. In 2025 plans were under way to restore the building to its original design and for it to become the home of a local musical organization. |

=Membership statistics= | =Membership statistics= | ||

| Line 98: | Line 98: | ||

The Danzig church in the 19th and early 20th centuries maintained an extensive archive. Most of this material was destroyed at the end of World War II, but several items were rescued by Mennonite relief workers from North America and taken there in the late 1940s. The earliest item to survive is a Flemish record book containing baptisms 1667-1800, marriages 1665-1808, births 1789-1809, deaths 1667-1807, list of preachers and elders 1598-1807 (showing Dirk Philips as the first elder). There is also a two-volume family record book of the Flemish congregation begun in 1789. These books were housed at the [[Mennonite Library and Archives (North Newton, Kansas, USA)|Mennonite Library and Archives]] (Bethel College, North Newton, Kansas) from 1947 until 2009, and were then transferred to the [[Mennonitische Forschungsstelle (Göttingen, Niedersachsen, Germany)|Mennonitische Forschungsstelle]] in [[Weierhof (Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany)|Weierhof]]. A variety of other fragmentary and disparate scattered records are still housed at [[Bethel College (North Newton, Kansas, USA)|Bethel College]]. No known records of the Frisian congregation have survived. | The Danzig church in the 19th and early 20th centuries maintained an extensive archive. Most of this material was destroyed at the end of World War II, but several items were rescued by Mennonite relief workers from North America and taken there in the late 1940s. The earliest item to survive is a Flemish record book containing baptisms 1667-1800, marriages 1665-1808, births 1789-1809, deaths 1667-1807, list of preachers and elders 1598-1807 (showing Dirk Philips as the first elder). There is also a two-volume family record book of the Flemish congregation begun in 1789. These books were housed at the [[Mennonite Library and Archives (North Newton, Kansas, USA)|Mennonite Library and Archives]] (Bethel College, North Newton, Kansas) from 1947 until 2009, and were then transferred to the [[Mennonitische Forschungsstelle (Göttingen, Niedersachsen, Germany)|Mennonitische Forschungsstelle]] in [[Weierhof (Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany)|Weierhof]]. A variety of other fragmentary and disparate scattered records are still housed at [[Bethel College (North Newton, Kansas, USA)|Bethel College]]. No known records of the Frisian congregation have survived. | ||

| − | |||

Bibliography: | Bibliography: | ||

| − | |||

Epp, Waldemar. “Zur Kulturgeschichte Danzigs: Aus der Zeit der Reformation und des Dreißigjährigen Krieges,” ''Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter'' 40 (1983): 46-58. | Epp, Waldemar. “Zur Kulturgeschichte Danzigs: Aus der Zeit der Reformation und des Dreißigjährigen Krieges,” ''Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter'' 40 (1983): 46-58. | ||

| Line 284: | Line 282: | ||

==Bibliography of Original Article== | ==Bibliography of Original Article== | ||

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. ''Mennonitisches Lexikon'', 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. I, 390. | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. ''Mennonitisches Lexikon'', 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. I, 390. | ||

| − | {{GAMEO_footer|hp=|date= | + | {{GAMEO_footer|hp=|date=June 2025|a1_last=Thiesen|a1_first=John D|a2_last=|a2_first=}} |

[[Category:Places]] | [[Category:Places]] | ||

[[Category:Cities, Towns, and Villages]] | [[Category:Cities, Towns, and Villages]] | ||

[[Category:Cities, Towns, and Villages in Poland]] | [[Category:Cities, Towns, and Villages in Poland]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:07, 15 June 2025

Beginnings

The date of the earliest Anabaptist or Mennonite presence in Danzig/Gdańsk is not known. Danzig was a major trading center, a Hanseatic city, and closely connected with the Netherlands. In the second quarter of the 16th century, there may have been groups or individuals present in the region who were generic religious dissidents but could not be clearly categorized as Anabaptists. Well-established trade routes brought immigrants from the Netherlands, but there were also immigrants to the Vistula Delta from other regions, such as Moravia to the south. It is likely that the Anabaptists of Danzig and its region drew on both immigrants and local residents, although the longer-term orientation was strongly towards the Dutch immigrant element. The lack of organized persecution of Anabaptists in the Danzig region (in contrast to other areas of Europe) means that documentation about the early years is quite sparse. Danzig and other Hanseatic cities issued statements against Anabaptists during the Anabaptist occupation of Münster in 1534-1535 but it seems likely that these were driven not by the actual presence of Anabaptists in Danzig but by imagined fears of a Münster contagion.

Anabaptist and Mennonite presence in the Danzig region was facilitated by the diversity of jurisdictions over different areas in the immediate area of the city and even within the city. The regional Catholic bishop had authority over land that ran up to the city walls, and other church organizations, such as monasteries, had authority over certain properties. The city itself had authority over fairly large areas of rural land outside the city walls. The Polish crown had authority over certain pieces of land. Farther out in the countryside, other cities, towns, church institutions, and occasionally nobles had control over certain areas. The economic and political interests of these various authorities were never well aligned, so Mennonites could find niches in which they would be tolerated, and could often find defenders against harassment whose interests temporarily aligned with theirs or who had common opponents.

One of the earliest concrete indications of an Anabaptist presence in Danzig is Menno Simons’ letter of 1549 to followers in the region. In the letter, Menno refers to at least one earlier visit there. By this time there seems to have been an organized congregation in existence. At some point after the middle of the 16th century, Dirk Philips came to Danzig from the Netherlands. He is considered the first elder of the Danzig congregation. Dirk also came to be tangled up in the Flemish-Frisian division that defined the Mennonite organizational landscape for the next few centuries.

Flemish Anabaptist refugees had settled in Friesland and differences arose between the refugees and the local Anabaptists. The two groups formally split in 1566. Dirk Philips had been called from Danzig to mediate and ended up taking sides with the Flemish, even though he himself was from Friesland geographically. He died in Friesland and never returned to Danzig. The labels Flemish and Frisian quickly became partisan categories rather than references to actual geographic origin, as Dirk’s case shows. Both parties quickly split into numerous smaller splinter groups among themselves. In the Netherlands, this division gradually faded away over the next century and was superseded by other divisions. In the Vistula Delta, where congregations had tended to adhere to the more hard-line splinter groups, the division remained alive into the 19th century.

Despite Dirk Philips’ participation, the Danzig congregation seems to have resisted for some years being pulled into the partisan camps. The elder after Dirk Philips, Quirin Vermeulen, kept the congregation together for an extended time after the split took place in the Netherlands. In 1588, the elder from the Frisian congregation at Montau, Hilchen Schmidt, arranged to have Vermeulen deposed, and this led to the formation of separate Frisian and Flemish congregations in Danzig. The Flemish were colloquially known as “fine” (fein) or “clear” (klar). The Frisians were “coarse” (grob) or “worried” (bekümmert). The origin and logic of these nicknames “klar” and “bekümmert” is not known. The Frisians remained the smaller group numerically throughout the course of their existence. Vermeulen continued to be active after being deposed as elder and is remembered for arranging for the publication of a Dutch-language Bible in the suburb of Schottland in 1598.

Where the congregations met in the early decades is not known. In late 1638 a member of the Frisian congregation purchased a lot outside the Neugarten gate for a church building and poor house. Ten years later, in 1648, a Flemish member purchased a lot in the city for its building and poor house. These properties technically remained in the ownership of individual members because the congregations had no legal existence in themselves. In 1713 the Frisian property fell outside of congregational ownership through inheritance by a non-Mennonite heir and had to be re-purchased by a member. There is some documentation that in late 1732 the Flemish were able to purchase their property in the city, but it is unclear whether this was simply some kind transaction among individuals or whether the congregation was given some kind of corporate status under city law at the time.

Congregational life in the 17th and 18th centuries

With much Mennonite residence and business activity concentrated in areas immediately outside the city walls, they received repeated setbacks and economic damage with frequent military conflicts during the 16th-18th centuries, which often led to destruction of buildings outside the city walls during sieges of the city. Conflicts included the First Northern War or Seven Years War of the North (1563-1570), the Second Northern War (1655-1660, known as the “Deluge” in Polish memory), the Great Northern War (1700-1721), the War of Polish Succession (1733-1736), and the Napoleonic wars of the early 19th century.

The Flemish church building and alms house were destroyed in the Russian siege of 1734. The Frisian building was remodeled in 1788 and an organ was added. The Flemish also remodeled in 1805-1806 and added an organ against significant opposition. A hand written organ chorale book survives from this time (now at the Mennonite Library and Archives, Bethel College, North Newton, Kansas). The Frisian building was destroyed during the French siege of 1806 and both groups then merged on 22 May 1808, and used the Flemish building until it too was destroyed in 1813. At the time of the merger the Frisians numbered 166 members and the Flemish around 700. The united congregation dedicated a new building at a new location on 12 September 1819.

Despite the relatively low level of persecution of Mennonites in the Danzig region, for most of their centuries of residence there they were second-class inhabitants and were subject to petty harassment. It seems likely that many of the attacks on them were not intended to be seriously carried out but were more along the order of rhetorical displays or political ploys in conflicts that did not have directly to do with the Mennonites. In many cases, these attacks were deflected by bribery; Mennonites paid “donations” or “loans” and were then left alone until the next time that a more powerful party thought they could extract more money.

Examples can be found almost continuously from the mid-16th century into the 18th century. In 1556 the Polish king Sigismund II Augustus issued an edict against Anabaptists. In 1566 the city of Danzig published an edict expelling Anabaptists by Easter (which obviously was ignored). In 1571 at a regional political assembly at Torun, Danzig representatives complained of dangerous sects on the bishop’s land outside the city walls (motivated by economic competition). In May 1572 and April 1573, decrees were posted at the Artushof, the merchants’ meeting place, expelling Anabaptists and Mennonites. In August 1578, the guilds (who were Danzig citizens but were not the ruling class in the city) complained of Anabaptists coming from Friesland. In summer 1582, a rural group living on city-controlled land, “derisively referred to as Rebaptizers or Mennonites,” petitioned the city council against requirements to participate in the state (Lutheran) church. This may be the earliest usage of the term “Mennonites” as a self-identification in the Danzig area. In April 1613, the city council noted that Mennonites did not serve as soldiers and so made a monthly donation to support others to do so. In 1624, Mennonites were required to find military substitutes or pay a fee for such purposes.

Some harassment revolved around economic issues. In October 1623, a privilege granted by the Polish king and the city council allowed free participation in the lace trade; apparently there had been an attempt by opponents to exclude Mennonites. In March 1629 the city council said Mennonites were not required to join the lace makers guild; it could be a free trade. Apparently there was no lace making guild in Danzig until Mennonite lace makers became active and then a guild was formed to oppose the outsider craftspeople. In November 1632 the city council again affirmed Mennonite freedom to conduct the lace trade. In April 1633, the Polish king Wladislaw IV told the city council that Mennonites had to take an oath to the king or leave in four months. In January 1636, there was a mandate from the king to Danzig that Dutch persons and Mennonites were not allowed to buy grain and that Mennonites should be expelled. The city council routinely ignored such mandates from the king; the city used every opportunity to maintain its independence and resist imposition of political control from outside. In the early 1640s, there was another attempt to ban Mennonite lace makers from the city. The Mennonites appealed to the king, and the royal representative in the city came to their defense in February 1643. He was a Calvinist, the king was Catholic, and the city was Lutheran. The royal representative argued that since the Lutherans were always complaining about persecution from Catholics, they should not set a bad example by persecuting others. In 1644 the shopkeepers guild interfered with Mennonite lace makers, having a shipment of raw materials stopped in Graudenz. In December 1644 a royal charter guaranteed Mennonites freedom of trade. In March 1648 a city council decision separated lace making from the trade in raw materials for it and the retail sale of lace; this was intended to restrict Mennonites economically by narrowing the scope of their craft. In December 1658, the city council stopped enforcement of the 1648 lace decision, but in 1663 Mennonites were again restricted in lace trade on the basis of the 1648 decision. In October 1666, Mennonite lace makers petitioned the city council defending their legal rights, referring back to the October 1623 privilege and asking for a reversal of the 1648 restriction; it is not clear what the city council decided.

Various confrontations in other areas besides lace making continued in the 17th century. In 1650 the city council nullified a decision of March 1633 that had allowed Mennonites to own property in the suburbs under city control. In July 1657, the guilds petitioned that no Mennonites should be allowed to have a retail shop except the refugees from the burned suburbs (this was in the context of the Second Northern War). In 1660 an anonymous pamphlet Informatio contra mennonistas was distributed in Danzig. In September 1664 another guild petition against Mennonite trade appeared, which referred to the 1636 order about Mennonite grain trade. In April 1666 the city council meeting noted that the 1650 decision about property ownership was not being strictly observed (as was the case with many such anti-Mennonite decisions). In 1669 a question arose about whether a Mennonite (not allowed to be a citizen) could own or invest in a merchant ship; some wanted to only make an exception for one individual. The outcome in the case is unclear; the city council apparently favored allowing ownership. In 1670 there was a quite murky series of attacks from the Polish king and involving various officials, the city council, and various monetary payments. In 1675 another anonymous Latin pamphlet against Mennonites appeared. In August 1675 there was a ruling that each Mennonite household had to pay 300 florins “protection money;” this seems to have developed out of a city tax on foreigners. In 1676 at a regional legislature in Marienburg, the city of Danzig was put on the defensive, being accused of coddling Mennonites and thus causing God to send debilitating floods on the region. In October 1677, the city council again had to defend Mennonites against guild complaints. In May 1681, the Netherlands government protested to the city about the Mennonite “protection money;” the Danzig Mennonites had protested that they should not have to pay since they were not foreigners, but then found themselves being defended by a foreign government.

Some confrontations had more directly to do with religion. In 1678 Mennonites were accused of being anti-Trinitarians. There was an interrogation before the Catholic bishop, in which the Flemish preacher Georg Hansen was the most prominent Mennonite participant (both Flemish and Frisian representatives participated). It is interesting that, while the city was officially Lutheran, it was the Catholic bishop who carried out this harassment of the city’s Mennonites. Also in 1678 there was a riot in Danzig by Lutherans against Catholics and also against Mennonites, during which a Carmelite monastery looted and burned. In 1687 the Jesuits asked Mennonites to build them a clock tower; the Mennonites gave a donation. In April 1688 a city official asked Mennonites for money towards building a Lutheran church in the suburb of Ohra. In June 1699, the Catholic bishop ruled that Mennonite theology was acceptable. It is unclear if this was the very delayed conclusion to the 1678 interrogation or if this was a new round of theological harassment.

During the 18th century, these confrontations gradually diminished. In 1708 Mennonites petitioned against “protection money.” Mennonites had also recently “loaned” money to the city and there were negotiations about these matters, but it is not clear what the result was. The topic of “protection money” became quiet for several decades. In 1732 Danzig Mennonites gave monetary aid to the Salzburg Protestants who were on their way from Austria to settle in East Prussia, replacing Mennonites who had just been expelled from there. In 1748-1750 there were more attacks on Mennonite economic activities by the guilds, part of a broader revolt against the Danzig establishment by the lower and middle classes. From 1749-1762 Mennonite merchants were apparently prohibited from selling anything but brandy (although Hermann G. Mannhardt’s congregational history describes this as something more complicated). This led to a noticeable Mennonite economic decline and prompted some Mennonites to move away to Königsberg or Amsterdam. In January 1750, a new form of the “protection fee” was imposed, a total of 5000 florins. It now had to be collected by the two congregations rather than the city. In 1755-59 the fee was reduced because economic restrictions had made Mennonites unable to pay. The new form of the fee also led to internal divisions over who should pay what share - Flemish versus Frisians, wealthy versus poor members.

After the first partition of Poland, Danzig remained part of Poland. In 1783, the Prussians who now controlled the rural areas around Danzig imposed a blockade of the city, partially as a result of complaints from Mennonites residing in the suburb of Altschottland and other areas under Prussian rule that Danzig authorities had prevented them from getting grain brought to them on the Vistula river. The blockade divided the congregation, with city members (still part of Poland) blaming rural members (under Prussian rule) for the blockade and economic hardship.

Mennonites in the Vistula Delta region became known for involvement in liquor distilling. Presumably this was another niche where a guild did not exist and thus allowed Danzig Mennonites to practice the craft with less opposition. In Danzig itself, Ambrosius Vermeulen started a distillery at the House of the Salmon (Zum Lachs, Pod Łososiem). The business became widely known for its Danziger Goldwasser, a liqueur containing edible gold flakes. Zum Lachs passed out of Mennonite hands sometime in the 18th century, but Goldwasser continued to be served at the same location in Gdańsk.

In looking back to the 17th and 18th centuries, historians have often associated Danzig Mennonites with artistic and engineering endeavors. A prominent name was Adam Wiebe or Wiebe Adam. (Wiebe may have actually been his first name rather than a surname, with Adam being a patronymic: Wiebe son of Adam.) Adam Wiebe is mentioned working for the city of Danzig as early as 1616. He is remembered outside of Mennonite circles as the first engineer to use an aerial tramway for moving fill dirt when he was working on fortifications for the city in 1644.

Other names mentioned are Anthony van Obbergen, an engineer (late 16th-early 17th centuries); the von dem Blocke family (father Wilhelm and sons Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, during the first half of the 17th century); Jacob Joosten, a hydraulic engineer (later 17th century); and Peter Willer, a builder and copper engraver (late 17th century).

For all of the above, it is not possible to confirm that they were actually Mennonites. The claim that they were Mennonites relies mostly on their apparent connections with the Netherlands and other fragments of circumstantial evidence. It may be the case that some of them had been Mennonites in the past and later joined the official church or the Reformed church, or that they had other family members who were Mennonites, but their actual Mennonite connection is not well established. Hermann G. Mannhardt does not mention any of these artists and engineers in his congregational history, presumably because he did not believe they were Mennonites.

One case of an artistic family in this era who were clearly Mennonites is the Seemann family. Enoch Seemann the Elder was banned by the Flemish congregation leader Georg Hansen for violating the second commandment by painting portraits. Seemann in 1697 published a pamphlet harshly attacking Hansen, but gave up portraits and restricted himself to landscapes and other subjects. None of his works survive. His son Enoch Seemann the Younger (born ca. 1694 in Danzig) later moved to London and became a prominent portrait painter there.

Another clash over how to relate to other Mennonites and to the non-Mennonite environment in this time period came in the form of the Wig War (Perückenstreit in German). In 1726, a Dutch Mennonite Cornelius de Vogel Leonhards moved to Danzig and wanted to join the Frisian congregation. He wore a wig and at the time wigs were common among urban Dutch Mennonites. The Danzig Frisian elder Hinrich van Dühren refused to serve communion to the new member. Wigs gradually came to be a fashion also in Danzig and the resistance of the elder led to communion being suspended for several years. In 1739 a group of young wig wearers somehow got city administrators involved in the clash and the elder van Dühren was put under house arrest. A new co-elder, Jan Donner, was elected. Van Dühren obviously refused to confirm him in office and the elders of the rural Frisian congregations also refused to get involved. The congregation or some of its members requested an elder to be sent from the Netherlands to help with the dispute, but Donner died suddenly. Eventually an elder Adrian Koenen came from the Netherlands and constructed a shaky agreement between the two sides. Communion was served again on 2 October 1740. The wig wearers were allowed to stay away when van Dühren presided and were serve by Koenen (and later by another visiting elder from the Netherlands).

The difficulties did not end here. In 1745 baptism was cancelled because of the perception of too fashionable dress among the young men. (Van Dühren was still elder and died in 1746.) In 1766, according to the chronicle of the rural Frisian congregation at Orlofferfelde, there was a general meeting of Frisian leaders because some members from Danzig were coming to communion at Orlofferfelde because they were still angry about the Wig War (and some members from the Thiensdorf congregation were coming to Orlofferfelde because of a dispute there). The meeting decided that members should get communion in their home churches except in cases of emergency. The Orlofferfelde elder was opposed to this coercion of conscience but was outvoted.

German replaced Dutch as the written and spoken language for church activities in the mid 18th century. It seems likely that everyday language usage would have changed earlier. In 1768 the Flemish published a catechism in German, replacing Georg Hansen’s 1671 confession in Dutch. On 1 January 1771, a local Flemish preacher gave his sermon in German rather than Dutch for the first time. (Visiting Flemish elder Gerhard Wiebe from Elbing had preached in German in Danzig as early as 1762.) The Frisians had switched to German earlier, but it is unclear exactly when. The language transition happened in an era immediately leading up to the partitions of Poland, in a time of growing Prussian influence, which may have made it seem that the future of Danzig was German-speaking.

Danzig was the starting point for the Mennonite migration to Russia in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In August 1786, a letter from Russian representatives was read in both Danzig churches with an invitation to settle in Russia. In fall 1787, Jakob Hoeppner and Johann Bartsch returned from a visit to Russia, having viewed possible settlement locations. Both of them were from Danzig, Hoeppner from the Flemish congregation and Bartsch from the Frisians. They had gone to Russia without notifying church leadership. This maintained plausible deniability for the church leaders, since the city had forbidden the churches to interact with the Russian agents. This initiation of the migration took place in the context of the partitions of Poland, when Danzig was cut off from its hinterland by the Prussian occupation of the surrounding area. Exact numbers of those who left the Danzig congregations for Russia are not clear, but there were two waves of migration in this time period, first in the 1780s and again around 1804.

Danzig Mennonites under Prussian rule

In April 1793 Danzig came under Prussian control in the second partition of Poland. Special taxes on Mennonites were eliminated. In 1800 Mennonites gained the right to citizenship by a royal decree that eliminated city regulation of citizenship. Mennonites still had to pay a 6% surcharge when buying real estate. In January 1847 that surcharge was eliminated by Mennonites who were then on the city council. Danzig Mennonites seem to have been prominent in urban life out of proportion to their numbers, although tracing specific stories is difficult. Hermann G. Mannhardt in his congregational history stated that Mennonites continuously had at least one member on the Danzig city council from 1817 up to his own time around 1920. One prominent member in science was Hugo Conwentz (d. 1922), long-time director of the West Prussian Provincial Museum and mostly known as a leader in environmental conservation.

Many organizational changes took place in the decades after the Flemish-Frisian merger of 1808. One such change was the transition to paid clergy instead of the selection of leadership from within the congregation. In October 1824, the Danzig congregation received a letter from Jacob van der Smissen, pastor at the Mennonite church in Friedrichstadt in northeastern Germany. He was looking for a paid pastoral position; his felt his congregation was too small and he wanted to serve a bigger one. Danzig at first said no; then in summer 1825 van der Smissen visited Heubuden, Elbing, and Danzig. He gave a guest sermon in Danzig which was well received. At Danzig, the existing ministers were elderly and no one in the congregation wished to be elected as preacher or elder. In addition, a parsonage had been donated by a woman who wanted the congregation to have a full-time pastor. The congregation hired van der Smissen and he moved to Danzig in June 1826 (and lived in the parsonage). The rural group of members objected and seceded to become a subsidiary of the rural Fürstenwerder congregation. Van der Smissen was used to wearing Protestant clerical garb and had to adjust his style to different expectation in Danzig. Later in 1826 both existing elders died, leaving van der Smissen as the senior pastor. He stayed until 1835 and left amid conflict.

For most of the Danzig congregations’ existence, there had been a group of rural members (apparently all Flemish) who lived on city-controlled farming land away from the city and its immediate suburbs. The group was often known under the village name of Neunhuben. This rural group had somewhat of a separate identity from the city congregations. In 1791 rural group became an independent congregation while continuing to be under the general supervision of the Danzig Flemish elder. In 1844 this group built a small church building at Quadendorf and continued as part of the Fürstenwerder congregation.

In 1836 the congregation hired a new pastor, Jacob Mannhardt, who also came to Danzig from the Friedrichstadt congregation. He was a first cousin once removed of van der Smissen (Mannhardt’s mother was a van der Smissen). Mannhardt had an almost 50 year pastorate and did much to shape the congregation in its last century.

In 1879 a new assistant pastor was hired, Hermann G. Mannhardt, a nephew of Jacob. Hermann formally joined the church at this time, which apparently meant that he had previously been a Protestant church member rather than a Mennonite. Both Mannhardts had Protestant theological university training.

In 1845 the congregation wrote a constitution and received limited incorporation through royal decree, allowing it to have a legitimate existence as a recognized legal entity rather than having to conduct all of its business via individual members. In 1887 the congregation was fully incorporated under normal German corporate law, based on a new constitution.

Jacob Mannhardt died in 1885 and Hermann became the senior pastor, continuing for more than 40 more years until his death in 1927. Both Mannhardts were active in German Mennonite activities beyond the local congregation. Jacob Mannhardt founded the German Mennonite newspaper Mennonitische Blätter in 1854. Herman G. Mannhardt helped start the Vereinigung der Mennoniten-Gemeinden im Deutschen Reich in 1886.

The most prominent issue of the 19th century was military conscription. Poland had no national conscription; this only was an issue for Mennonites who lived in cities and might be called on for local militias and self defense forces. Prussia did have a conscription system and imposed it on the territories taken from Poland. Mennonites were exempt in return for a special tax payment and severe restrictions on real estate purchasing and on mixed marriages with non-Mennonites. In 1848 a divisive congregational meeting allowed members to join local civic militias (which meant carrying weapons). In November 1867 the new Prussian military conscription law eliminated Mennonite exemption, and in March 1868 a cabinet order from the king defined Mennonite military service to be in noncombatant roles. A few families from Danzig decided to emigrate at this time; probably the most prominent was Ludwig E. Zimmermann, a deacon, but the rest of the church leadership and most members continued to accept the evolving conditions. In October 1870 the church officially dropped its requirement that members refuse military service, but continued to recommend noncombatant service. It also dropped opposition to mixed marriages, allowing membership transfer from other churches.

Danzig in the 20th century

Because of the dispersal of the congregation and the destruction of archives at the end of World War II, our knowledge of the last several decades of the congregation’s story is diminished. Up until World War I, it continued on its trajectory of development of the last decades of the 19th century. In 1901 the congregation built a care home for aged and poor members, which also housed the congregational archives. In March 1914, the organ was renovated and electric lighting was installed.

During World War I, 250 men served in the German military, almost half of the baptized male membership. We do not know what proportion served in noncombatant roles. Twenty-eight were killed. According to Hermann G. Mannhardt, there were 62 officers among the 250.

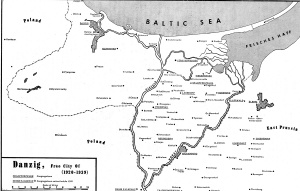

World War I brought dramatic change to Danzig. In late 1920, the city and much of the Vistula Delta became the Danzig Free State, independent of both Germany and the re-created Poland. The 6000 Mennonites in the Free State made up 2.5% of the total population. There were three Mennonite delegates in the 1920 legislature of the new city-state (2.5% of the members). Mennonites had equal rights and were allowed to affirm instead of swearing oaths.

In 1927, long-time pastor Hermann G. Mannhardt died and Erich Göttner became the new, and last, pastor. Göttner had been baptized in the Danzig congregation and spent much of his childhood and youth there. He studied Protestant theology at several German universities and then had been pastor of several Mennonite congregations in western Germany before returning to Danzig. Göttner continued the Danzig tradition of active involvement in German Mennonite denominational organizations beyond the local congregation.

The last few years of the Danzig congregation are overshadowed by National Socialism. In May 1933, the Nazi party won a narrow majority in the Danzig legislature; this was a few months after Hitler had become German chancellor. World War II began with combat in the Danzig harbor and elsewhere in the city. Many members served in the German military and were members of the Nazi party, but we do not have reliable statistics. Erich Göttner was drafted into the German army in July 1944 and is believed to have died as a Soviet prisoner of war in 1945. Most of the membership who were still in Danzig in 1945 fled to avoid the advance of the Soviet Red army and dispersed to western Germany or to refugee camps in Denmark. There are no good statistics about where former Danzig members ended up; it seems likely that most stayed in western Germany, with some migrating to South and North America.

The Danzig Mennonite church building survived World War II, in contrast to much of the rest of the city. In 1947 the Polish Communist government granted permission to a Pentecostal congregation to use the building and nearby parsonage. Restoration of the buildings lasted until 1958 because of government delays. In the immediate post-war years, the North American Mennonite Central Committee had a relief program in the area, and the “seagoing cowboy” program brought livestock by ship into the area to aid the revival of agriculture. Both of these programs brought North American Mennonites to Danzig and the Vistula Delta, who visited various Mennonite sites such as the Danzig building.

In 1972 the Pentecostal congregation obtained actual legal ownership of the building. In 1989 they took formal ownership of the parsonage and in 2003 the care home. The large, active congregation continued up to 2025 to use the 200-year-old former Mennonite building as one of their meeting places in Gdańsk. In 2025 plans were under way to restore the building to its original design and for it to become the home of a local musical organization.

Membership statistics

The number of Mennonites in Danzig is difficult to determine for much of its history. A list from about 1660 counted about 47 heads of families, but probably does not include all families living in the immediate area of the city. A 1681 list had about 114 families. Hermann G. Mannhardt in his history thought that membership was the highest during the years 1690-1750 (although in his own era in the 20th century it was probably higher). During the 1709 plague, 160 adults and 230 children died in the Flemish group. In 1749 the Flemish elder Hans von Steen listed 240 households (excluding rural dwellers). At the 1808 merger of the Frisians and Flemish, the Frisians numbered 166 and the Flemish ca. 700. Surviving statistics from the 19th century are: 1831, 635 members; 1852, 410; 1882, 448 plus 210 children; 1900, 735. Membership numbers increased rapidly in the 20th century, passing 1000 in 1905, and 1200 in 1911 and 1921. Mannhardt recorded that the 250 men who served in the military in World War I made up almost half the baptized membership. In 1940 (the last surviving statistic), there were 1020 members and 173 children.

Church records

The Danzig church in the 19th and early 20th centuries maintained an extensive archive. Most of this material was destroyed at the end of World War II, but several items were rescued by Mennonite relief workers from North America and taken there in the late 1940s. The earliest item to survive is a Flemish record book containing baptisms 1667-1800, marriages 1665-1808, births 1789-1809, deaths 1667-1807, list of preachers and elders 1598-1807 (showing Dirk Philips as the first elder). There is also a two-volume family record book of the Flemish congregation begun in 1789. These books were housed at the Mennonite Library and Archives (Bethel College, North Newton, Kansas) from 1947 until 2009, and were then transferred to the Mennonitische Forschungsstelle in Weierhof. A variety of other fragmentary and disparate scattered records are still housed at Bethel College. No known records of the Frisian congregation have survived.

Bibliography:

Epp, Waldemar. “Zur Kulturgeschichte Danzigs: Aus der Zeit der Reformation und des Dreißigjährigen Krieges,” Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter 40 (1983): 46-58.

Grigoleit, Eduard. “Danziger Mennoniten aus dem Jahre 1681,” Danziger familiengeschichtliche Beiträge 2 (1934): 124-127.

Kobe, Rainer. “Die Vermeulen-Bibel des Wilhelm von den Blocke von 1607,” Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter 67 (2010): 69-75.

Kobe, Rainer. “Wie mennonitisch war die Danziger Künstlerfamilie von Block?” Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter 66 (2009): 71-84.

Mannhardt, H. G. The Danzig Mennonite Church: Its Origin and History from 1569-1919. Trans. Victor G. Doerksen. North Newton, KS: Bethel College, 2007.

Mannhardt, H. G. Die Danziger Mennonitengemeinde: Ihre Entstehung und ihre Geschichte von 1569-1919. Danzig: Danziger Mennonitengemeinde, 1919.

Penner, Horst. “Verzeichnis der Mennoniten die im Jahre 1661 innerhalb der Stadt Danzig, vorm Hohen Tor und auf Neugarten wohnten,” Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter 24 (1967): 47-53.

Plett, Harvey. “Georg Hansen and the Danzig Flemish Mennonite Church: A Study in Continuity.” Ph. D. dissertation, University of Manitoba, 1991.

Quiring, Horst. “Aus den ersten Jahrzehnten der Mennoniten in Westpreußen: Zugleich ein Beitrag zur Sippenforschung,” Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter 2 (1937): 32-35.

Quiring, Horst. “Der Danziger Perückenstreit,” Christlicher Gemeinde-Kalender 45 (1936): 98-102.

Additional Information

This article is based on the original English essay that was written for the Mennonitisches Lexikon (MennLex) and has been made available to GAMEO with permission.

Original Mennonite Encyclopedia Article

By Christian Hege and Harold S. Bender. Copied by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, p. 7. All rights reserved.

Danzig, a government district (Regierungsbezirk) of the province of West Prussia, before the partition in 1918 containing nearly one-third of the Mennonites living in Germany, most of them in the triangle formed by Danzig (city), Elbing and Marienburg. Whereas in the townships of Marienburg and rural Elbing the number of Mennonites decreased after World War I, it rose in the townships of Danzig-City, Danzig-Lowland, Danzig-Heights, and Elbing-City. Also in the township of Neustadt, particularly in Zoppot, more and more Mennonites settled.

The district contained the following congregations up to the evacuation of all Germans under the Polish occupation: Fürstenwerder with 561 souls (in 1921), Heubuden 1,623, Ladekopp with Orlofferfelde 1,150, Tiegenhagen 823, and Thiensdorf-Markushof 1,083, Elbing-City 400, Elbing-Ellerwald 736, Rosenort 718, Danzig City 1,360, and Danzig-Lowland-Quadendorf 50. Parts of Fürstenwerder and Tiegenhagen also belonged to Danzig-Lowland.

From 20 January 1920 to August 1939 the old district of Danzig was displaced in part by the Free City of Danzig, a politically independent state under the League of Nations. In 1939-1945 it was called "Regierungsbezirk Danzig," and was part of the "Reichsgau Danzig-Westpreussen." With the conquest of Germany by the Allied powers in 1945 and the reconstitution of Poland, the area was incorporated into the Polish governmental system, with the Polish name Gdansk.

In 1947 the Mennonite Central Committee established a relief program in the Danzig area, to which it had been directed by the Polish government, with headquarters in Tczew (Dirschau). It conducted relief there until the fall of 1948, when the Polish government in effect compelled the transfer of the work to Nasielsk near Warsaw. During the 1947-1948 period many Mennonites were aided together with the general population. In 1947 there were still over 200 Mennonites in this region, nearly all of whom were permitted to go to Germany in 1947-1949. A few individuals and one or two families of Mennonites have remained in the city or its environs.

Census figures show the following Mennonite populations in the various parts of the district:

| Name | 1861 | 1871 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 | 1910 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elbing City | 2,075 | 405 | 535 | 477 | 591 | 606 |

| Elbing Rural | 1,491 | 1,387 | 1,329 | 1,172 | 953 | |

| Marienburg | 5,343 | 5,420 | 4,999 | 5,014 | 4,928 | 4,767 |

| Danzig City | 459 | 486 | 582 | 617 | 626 | 639 |

| Danzig-Lowland | 283 | 275 | 403 | |||

| Danzig-Lowlands / Danzig Heights | 544 | 428 | 397 | |||

| Danzig-Heights | 72 | 87 | 138 | |||

| Dirschau | 99 | 62 | 73 | |||

| Dirschau / Stargard | 52 | 69 | 65 | |||

| Stargard | 13 | 20 | 29 | |||

| Berent | 12 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 6 | 1 |

| Karthaus | 3 | 7 | 5 | 5 | ||

| Neustadt | 13 | 88 | 161 | |||

| Neustadt / Putzig | 10 | |||||

| Putzig | 2 | 3 | 6 | |||

| Totals | 8,485 | 8,300 | 7,979 | 7,937 | 7,863 | 7,781 |

Bibliography of Original Article

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. I, 390.

| Author(s) | John D Thiesen |

|---|---|

| Date Published | June 2025 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Thiesen, John D. "Danzig (Poland)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. June 2025. Web. 19 Jan 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Danzig_(Poland)&oldid=180855.

APA style

Thiesen, John D. (June 2025). Danzig (Poland). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 19 January 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Danzig_(Poland)&oldid=180855.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.