Refugees

Refugees, victims of wars, revolutions, and ideologies, are far more numerous in the 21st century than are victims of natural disasters. To escape persecution, torture, or death because of race, religion, or political views, refugees flee the country of their origin in search of asylum. According to the United Nations High Commissioner of Refugees (UNHCR) there were 27.1 million refugees in 2022 (including 5.8 million Palestine refugees), many crowded into camps -- those inhuman institutions with their characteristic atmosphere of despair, hopelessness, and the curse of enforced idleness. In 2022 the UNHCR listed five countries as the originating country for 68% of all refugees: Syrian Arab Republic (6.8 million), Venezuela (4.6 million), Afghanistan (2.7 million), South Sudan (2.4 million), and Myanmar (1.2 million). In that same year, the following five countries hosted 38% of all refugees: Turkiye (3.8 million), Colombia (1.8 million), Uganda (1.5 million), Pakistan (1.5 million), and Germany (1.3 million).

In 2022 53.2 million more were "displaced persons" in their own countries who have been forced to flee their home communities for much the same reasons that refugees flee across national boundaries.

One of the most dramatic refugee movements in all history was the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt, their 40 years of wilderness wanderings, and their ultimate settlement in Canaan. For 3,000 years the Jews have been refugees. One of them wrote: "By the waters of Babylon, there we sat down and wept, when we remembered Zion" (Psalms 137:1). Joseph and Mary were refugees, caught in a political web not of their own making and fleeing out of fear for the safety of the infant Jesus (Matthew 2:13).

Persecution of those who dissented from official church law or doctrine, or both, produced some refugees during the Middle Ages: Jews (12th century ff.), the Cathari or Albigenses (12th-13th century ff), the Waldenses (12th century ff), the Lollards and Hussites (15th century). The wholesale religious wars and persecutions of the Reformation era produced even more refugees during the 16th and 17th centuries. Among those who most frequently found themselves fleeing for their lives were the Huguenots (French Calvinists) and Anabaptists.

The main records of Anabaptist persecution, torture, and death are Het Offer des Heeren (1562-63), The Martyrs' Mirror by Thieleman J. van Braght (1660), and the great Chronicle of the Hutterites ("Geschicht-Buch") about 1665. In the 16th and 17th century Anabaptists were driven from their homes and communities in Switzerland, Austria, Holland, France, Moravia and elsewhere. In the Swiss canton of Berne a special police called "Anabaptist-Hunters" (Täuferjäger) was employed to ferret them out and arrest them.

Mennonites also have a long history of aiding refugees. In 1553 North German Mennonites gave asylum to English Calvinists fleeing for safety from their Catholic queen. In the 1660s Dutch Mennonites sent large contributions to the Hutterian Brethren persecuted in Hungary, and likewise to the Swiss Brethren in 1672. In 1710 they organized the Foundation for Foreign Relief (Stichting voor Buitenlandsche Nooden) which helped 400 refugees from Switzerland settle in the Netherlands and contributed large sums of money to aid in the migration of Swiss Brethren from the Palatinate to Pennsylvania.

North American Mennonite assistance to people of their faith who came to Canada and the United States in large migrations in the 1870s (more than 18,000) and the 1920s (more than 20,000) might not be regarded as assistance to refugees because, although these people left Russia for a variety of reasons including lack of religious freedom, they would not all qualify as refugees under the current United Nations definition of a refugee. Theirs was a typical push-and-pull situation resulting in more or less normal immigration. The line between refugee and voluntary emigrant is still difficult to draw.

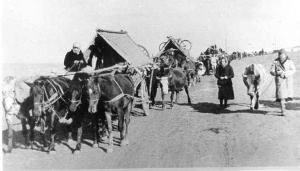

The Mennonites who left the Soviet Union in 1929 should probably be regarded as people whose journey began as emigrants but ended in a nightmare as refugees. What began as a small trickle of Mennonites in the summer of 1929 resulted in a flood of 13,000 - 14,000 refugees of Mennonite, Lutheran, Catholic, and other religious affiliations arriving in Moscow seeking to emigrate. This created a high stakes international incident involving diplomats and leaders from the Soviet Union, Germany, Canada, and other North American and South American countries.

Approximately 5,700 refugees from Moscow were able to emigrate to Germany. The remainder of those who had travelled to Moscow were dispersed by force to Siberia or sent home. Later escapees, births in the camps, and later refugees with special permission to join family members in Germany raised total numbers to 6,278. However, the death of 288 refugees, mainly children, reduced the numbers eligible to emigrate to about 5,990 refugees.

According to one report, by November 1932, refugees of all religious persuasions found new homes in the following countries: Brazil - 2,529; Paraguay - 1,572; Canada - 1,344; Argentina - 6; Mexico - 4; USA - 4; Europe - 458. Of the 3,885 Mennonites identified as part of this group, passenger lists indicate that 1,443 Mennonite refugees sailed for Paraguay and that 1,259 Mennonite refugees sailed for Brazil.

About the time of the Moscow disaster another group managed to escape over the frozen Amur River into Harbin, China. MCC assisted about 200 to settle in the United States, 373 in Paraguay, and 180 in Brazil. River of Glass by Wilfred Martens (Scottdale, 1980) tells this dramatic story.

World War II made many refugees, including more than 12 million in Germany alone. The first contact with Mennonite refugees from the Soviet Union was in mid-1945 when 33 showed up in Holland. With the assistance of T. O. Hylkema, pastor of the Mennonite church in Amsterdam, MCC negotiated an agreement with the Dutch government to provide asylum for more of these people. MCC and the Dutch Mennonites guaranteed full maintenance and onward movement at the earliest opportunity. To formalize and facilitate this arrangement a "Menno Pass" was issued to each refugee admitted into the country. All but one, who because of mental illness had to be institutionalized, left Holland within a year or two.

The open door to Holland and fear of being kidnapped by Soviets in Germany and forcibly returned to the Soviet Union made hundreds of Mennonites flee to the town of Gronau in Westphalia on the German-Dutch border. As the city became inundated with refugees and the news became public it attracted the attention of the Soviet authorities. Consequently under pressure from the USSR, Holland closed its borders but adamantly refused to return to the Soviet Union those Mennonites that had already been admitted.

The consequence of the refugee influx to Gronau was that MCC opened a major camp, with hospital, in that city. Meanwhile, a refugee camp was opened in Berlin, starting with 125 persons and closing nine months later, on 31 January 1947, with over 1,200 refugees. This group was joined by 300 from Holland and over 1,000 from Munich in South Germany and was the first major refugee transport and resettlement effort, of any group -- Mennonite or non-Mennonite -- to leave Europe after World War II.

Ultimately four transports left Bremerhaven, Germany, for South America with a total of 5,616 persons as follows: 1 February 1947 on the Volendam, 2,303; 25 February 1948 on the Heinzelman, 860; 16 May 1948 on the Charlton Monarch, 758; 7 October 1948 on the Volendam, 1,695.

The International Refugee Organization (IRO), the first international agency created by the United Nations in 1947, provided considerable funding for those refugees that were eligible according to the UN definition; the rest of the money needed to come from the Mennonite churches. The last Volendam transport included 751 Prussian and Danzig Mennonite refugees who settled in Uruguay and 115 non-Mennonites selected by the Society of Brothers for settlement in their Primavera colony in Paraguay. In addition to the temporary nine-month camp in Berlin and the Gronau camp, MCC also maintained camps at Backnang near Stuttgart and had special staff members at Falingbostel assisting those going to Canada and the United States as well as at Oxboel, Denmark, assisting the Danzig and Prussian refugees.

Many of the refugees from Russia and Prussia chose to stay in West Germany. To help them get established and also to prevent scattering, MCC provided funding and manpower for the construction of settlements (Siedlungen). Pax volunteers began in 1951 to build houses for them at Torney, Espelkamp, Backnang, Wedel, Enkenbach, and Bechterdissen, as well as for the Gemeinschaft der Evangelisch Taufgesinnter (Nazarenes) refugees in Taxach near Salzburg, Austria. No settlement was considered complete until a church building had been erected. A total of 486 Pax volunteers served for two years in Germany (76 in Austria). In 1948 MCC established Der Mennonit, a 16-page German monthly paper primarily for the benefit of the scattered refugees. In 1953 C. F. Klassen, special commissioner for MCC, initiated a systematic tracing service (Suchdienst) to facilitate the finding of scattered refugees in Europe and their relatives in Canada and elsewhere.

A new concern for refugees emerged in the Mennonite churches of Canada and the United States in the 1970s. Earlier efforts had concentrated mainly, though not exclusively, on helping Mennonites, but with the end of the Vietnam War in 1975 and the emergence of the "boat people" refugees, MCC turned to helping non-Mennonite refugees, primarily from southeast Asia but, after 1980, also from Central America. There were at least three reasons for this: first, Mennonites, rooted in Scripture, read often the words of Jesus, "I was hungry and you gave me food ... I was a stranger and you welcomed me." (Matthew 25: 35) Secondly, there was a realization that the 20th century had brought with it an entirely new phenomenon not known before, the difficulty of fleeing one country and the problem of entering another. With the emergence of passports and visas, the tightening of securities at borders and the ideological tensions there emerged the "stateless person," the unwanted refugee who often could not get out, yet could not get in. Thirdly, there was the deep involvement of the United States in the unpopular Vietnam war, and the long service of MCC and the Eastern Mennonite Board of Missions and Charities (MC) in Vietnam, providing much awareness of the post-war plight of these people, and perhaps also a sense of guilt.

At its annual meeting in 1980 MCC adopted a resolution on refugees resolving to "give special attention during the next three years to the needs of refugees in Africa, Southeast Asia, the Middle East and other regions." Assistance was to be in personnel, money, and material aid, helping refugees to return to the countries of their origin or resettling them elsewhere. Always there was to be a strong concern for the social and spiritual needs of these people.

As the linkages between revolutions and refugees, ideologies and homeless people, injustice and poverty became increasingly obvious, MCC attempted to work also at solving root causes. Peace and reconciliation efforts attained new meaning and urgency. Concern also shifted from non-Western countries, where refugees walked the lonely roads, to Canada, the United States, and Europe, where the weapons were made that drove these people from their homes and countries. In books like Making a Killing by Ernie Regehr the linkage was documented.

Concern was also directed to active involvement in nonviolent action, to shifting from traditional peacekeeping to active peacemaking (peace activism). Evidence of this shift and a greater readiness to engage in challenging the civil authorities was also seen in a refugee program called Overground Railroad (ORR). The ORR was started in 1983 as a service for Central American refugees by Jubilee Partners of Georgia; Reba Place in Evanston, Illinois; and MCC. It shuttled refugees from south Texas to host congregations in various parts of the United States and ultimately to Canada, where congregations often acted as official sponsors providing housing, food and clothing, orientation, and the necessary care and moral support. The ORR program, in addition to helping individual refugees and families, was a direct and bold challenge to the unjust United States refugee policy. During 1985 ORR assisted 200 refugees from Central America to reach haven in Canada, via Mennonites and other churches.

Canada has a long history of helping refugees. Since World War II more than a half-million refugees settled in Canada. MCC Canada on 3 June 1981, signed an "Extension of agreement with regard to the sponsorship and joint assistance of refugees" with the Canadian government, primarily at that time for the sake of helping refugees from Indochina. During a six-year period (1980-85) nearly 3,000 refugees were sponsored by Canadian Mennonites. From 1975 through 1986 4,216 refugees were sponsored to resettle in the United States through MCC US.

MCC's response to refugees has been to help them return to the country of origin if possible, to assist in resettling them in the country of their first asylum, or to resettle them in a third country. Assistance consists in food and clothing, medical and educational services, employment, training, and meeting agricultural, housing, social, and spiritual needs.

While the refugee problem is complex it can be said that wars and revolutions, ideologies, and intolerance are the chief culprits. Massive indifference is the major obstacle to solving the refugee problem.

Bibliography

An Annotated Bibliography of Mennonite Writings on War and Peace, 1930-1980, ed. Willard Swartley and Cornelius J. Dyck. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1987: 596-611.

Corporación Paraguaya, Inc. "1930 List of Transports: List of Members of Transport IV for Paraguay Leaving Mölln, Juy 12, 1930." Mennonite Central Committee: Paraguayan Immigration, 1920-1933, Corporación Paraguay, Inc. 1926-1952. IX-3-3, Box 11, File 11. Akron, PA: Mennonite Central Committee Archives.

Corporación Paraguaya, Inc. "1930 List of Transports: Transport V, List of the German Russian Mennonite Refugees Who Sailed for Paraguay, September 17, 1930." Mennonite Central Committee: Paraguayan Immigration, 1920-1933, Corporación Paraguay, Inc. 1926-1952. IX-3-3, Box 11, File 11. Akron, PA: Mennonite Central Committee Archives.

Epp, Frank H. Mennonite Exodus: The Rescue of the Russian Mennonites since the Communist Revolution. Altona, Man.: D.W. Friesen & Sons, 1962.

Fretz, J. Winfield. Pilgrims in Paraguay. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1953.

Friesen, Martin W., ed. Kanadische Mennoniten Bezwingen eine Wildnis. Kolonie Menno, Paraguay, 1977.

Komitee der Flüchtlinge, ed. Vor den Toren Moskaus. Yarrow, BC: Columbia Press, 1960.

Letkemann, Peter. "Mennonite Refugee Camps in Germany, 1921-1951: Part II - Lager Mölln." Mennonite Historian (December 2012). https://www.mennonitehistorian.ca/38.4.MHDec12.pdf.

Lopau, Christian. "Das Flüchtlingslager Für Die Rußlanddeutschen in Mölln 1929-1933." In Forschungen Zur Geschichte Und Kultur Der Rußlanddeutschen: 106–17. Essen: Klartext Verlag, 1997.

Neufeldt, Colin Peter. "Flight to Moscow, 1929: An Act of Mennonite Civil Disobedience." Preservings 19 (December 2001): 35–47. https://www.plettfoundation.org/files/preservings/Preservings19.pdf.

Norwood, Frederick A. Strangers and Exiles, 2 vols. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1969.

Pauls, Jr., Peter, ed. Mennoniten in Brasilien; Gedenkschrift Zum 50 Jahr-Jubiläum Ihrer Einwanderung: 1930 - 1980. Paraná State, Brazil: Witmarsum Colony, 1980.

Regehr, Walter, ed. 25 Jahre Kolonie Neuland Chaco-Paraguay (1947-1972). Karlsruhe: Heinrich Schneider, 1972.

Rose, Peter J. Working With Refugees, Proceedings of the Simon S. Shargo Memorial Conference. New York: Center for Migration Studies, 1986.

Savin, Andrey I. "The 1929 Emigration of Mennonites from the USSR: An Examination of Documents from the Archive of Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation." Journal of Mennonite Studies 30 (2012): 45–55. https://jms.uwinnipeg.ca/index.php/jms/article/view/1448.

Schirmacher, Hermann, ed. "Mennonite Passenger Lists for Brazil." Latin American Mennonite Genealogial Resources. 1 May 2021. Web. 17 January 2024. https://www.mennonitegenealogy.com/latin/Mennonite_Passenger_lists_for_Brazil.pdf.

Toews, John B. Lost Fatherland. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1967.

UNHCR: The UN Refugee Agency. "Figures at a Glance." Web. 23 August 2022. https://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html.

Unruh, John D. In the Name of Christ. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1952.

Willms, Henry J, George G Thielman, and Committee of Mennonite Refugees from the Soviet Union. At the Gates of Moscow: Or God’s Gracious Aid through a Most Difficult and Trying Period (an Eyewitness Report Concerning the Flight from Moscow to Canada, the Land of Freedom). Abbotsford, BC: Judson Lake House Publishers, 2010.

Additional Information

Search Mennonite Central Committee page for Immigration, Refugees and similar terms

| Author(s) | Peter J Dyck |

|---|---|

| Richard D. Thiessen | |

| Date Published | January 2024 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Dyck, Peter J and Richard D. Thiessen. "Refugees." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. January 2024. Web. 3 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Refugees&oldid=178140.

APA style

Dyck, Peter J and Richard D. Thiessen. (January 2024). Refugees. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 3 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Refugees&oldid=178140.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 5, pp. 753-756. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.