Architecture

1953 Article

What can be said about "Mennonites and architecture" is related mostly to their retaining accustomed architectural patterns and their creative efforts in adjusting them to new environments. As the Mennonites outside of Holland and Northwest Germany are predominantly a rural folk, the objects in which their architectural patterns found expression are mostly dwelling places; barns, and school and church buildings. Nowhere, however, has any characteristic or distinctive architectural style developed which was created by Mennonites.

There are two major sources of origin and lines of development for Mennonite culture including architectural patterns -- the Mennonites of Swiss background who migrated either directly from Switzerland to Pennsylvania or indirectly by way of Germany, during the early 18th century, and accepted the Pennsylvania-German architectural patterns, and the Prusso-German Mennonites of Dutch background who settled in the Vistula River Delta near Danzig and migrated to Russia at the end of the 18th century, whence some came to America in the second half of the 19th century.

The Swiss Mennonites, when leaving home and settling in South Germany, Alsace-Lorraine, Volhynia, Galicia, and America, adhered to their culture and traditions in their respective environments for a long time. In countries like South Germany, Alsace-Lorraine, and the Netherlands a gradual adjustment took place, while in countries with a definitely contrasting culture adjustment was much slower. This was the case in Volhynia, Galicia, and Pennsylvania. And yet the meetinghouses or churches of the Mennonites in South Germany and Alsace-Lorraine even in the 1950s indicated a direct expression of their straightforward Christian belief and practices.

It is of interest to note that in Switzerland, for instance at Langnau and Sonnenberg (Jeangisboden) and quite generally, the meetinghouse is built to look much like a dwelling house, actually inhabited by a family in the first story, with the church room or rooms in the second story. In some places a schoolroom displaces the family quarters on the first floor, as at Moron.

The Swiss and South German Mennonites and Amish who settled in Pennsylvania during the 18th century became an integral part of the developing Pennsylvania-German culture and made their own significant contribution to it. This culture is by background a composite of various South German cultural strains which were transplanted to Eastern Pennsylvania by representatives of the Lutherans, Reformed, Mennonites, Moravians, and some mystic and pietistic groups. Here in the new American environment under pioneer conditions the Pennsylvania-German culture emerged. The architectural patterns which the Pennsylvania-German Mennonites followed are for the most part an integral part of this culture. A visitor to the Pennsylvania-German country is most impressed by the unique barns which he finds not only in Pennsylvania, but wherever these people have moved during the past century in locations like Ohio, Indiana, Iowa, and Ontario. The barns including the motifs and decorative designs are also of South German background. J. J. Stoudt writes that the designs once had religious meaning, but Alfred L. Shoemaker's Hex, No! shows that they no longer have religious significance. According to Shoemaker the painting of barns in Pennsylvania was introduced around 1830. The "plain people" including the Amish and the Mennonites accepted this innovation but were reluctant to make use of symbols and decorative designs on their barns although they used them freely in penmanship and embroidery. In matters pertaining to dwelling places and other structures in the barnyard the Amish and Mennonites have more or less followed the prevailing practices of their respective communities.

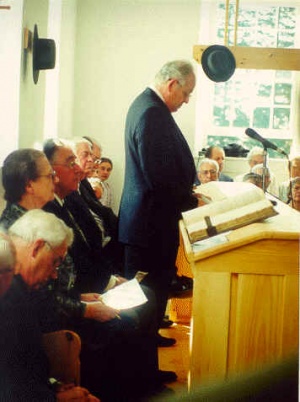

In their church, architecture, however, the Mennonites in Pennsylvania did not follow the prevailing practices of the "church people" neighbors, but went their own distinctive way. Their meetinghouse has an interesting history. During the 16th to 18th centuries when the Mennonites of Switzerland were outlawed and could not build churches or special buildings for worship purposes the worship had of necessity to be either in private homes or in the forests and deep mountain glens. No meetinghouses were built in Switzerland or neighboring Alsace and France before the second half of the 19th century. The Amish, being a conservative branch of the Mennonites, maintained the practice even in countries where there was no restriction along these lines. The Mennonites of colonial Pennsylvania (1683-1789), however, during pioneer days built log or stone buildings to serve as schools during the week and as churches on Sunday. Gradually separate buildings for each purpose were erected; usually close together, with a whitewashed stone type soon becoming predominant, later replaced by a brick structure. Originally the church building was very plain and similar to the school. As the congregations grew in size the buildings grew in length. The original meetinghouse usually had one entrance at the end or side; later, two -- one for men and one for women. A small porch at the entrance was in many cases extended across one entire side and end of the meetinghouse. Originally no paint was applied to the interior woodwork and furniture of the building. Men sat on one side and the women on the other on benches without backs. Hats and bonnets were hung on racks suspended from the ceiling over the benches. The ministers sat around a table at the wall opposite the entrance. Gradually a long pulpit was introduced, from which the sermon was delivered, backed by a long bench on which all the ministers sat during the service. Today the pulpits are largely modernized although the long bench is still commonly in use. In the Eastern Pennsylvania meetinghouses of the more conservative groups, no provision is made for pianos or organs, symbolism or art work, steeples and bells, stained glass windows, etc., even today. In the cemeteries near the meetinghouses small simple headstones bearing the names of the departed are found. Stoves were early placed into meetinghouses but lights only more recently with the advent of evening meetings. With the coming of Sunday schools and other activities of the congregations a basement was added.

The origin and development of the Pennsylvania German Mennonite meetinghouse is most closely related to that of the other plain people such as the Friends, and is most likely patterned directly after the Quaker meetinghouse which was brought from England. This meetinghouse type has spread to Virginia, Ontario, Ohio, and the western states where the architectural patterns underwent some modifications, especially in the Middle West. Smaller groups again under pioneer conditions and joined frequently by newcomers from Europe did not always maintain the structural design of the meetinghouse in its original form. Sometimes it was abandoned altogether and replaced by prevailing styles in the respective communities. Thus there was less uniformity along these lines among the Mennonites of Pennsylvania-German background in the Middle West and prairie states than was the case in Pennsylvania, Ontario, and Virginia. Under the impact of prevailing American architectural styles the more acculturated groups of Pennsylvania are less uniform in traditional meetinghouse structure than they formerly were. Some congregations have broken away completely and others are attempting to retain the good qualities and features in their adjustment to the needs and functions of a Mennonite congregation in our day.

It is possible though not likely that the early Mennonite meetinghouse of Pennsylvania was also influenced by practices common among the Mennonites of the Palatinate in South Germany. Until 1750 the Mennonites in the Palatinate had not yet been able to erect special houses for worship, and after this almost no emigrants crossed the Atlantic until after 1815. The first church buildings in the Palatinate were plain one-story structures with rectangular windows that gave little impression of being "churches." Some changes in both the exterior and interior took place during the 19th century. Organs were introduced and sometimes provisions for choirs were made. These changes usually came about in connection with a trained ministry which was gradually introduced from the beginning of the 19th century.

Before presenting the Prusso-Russo-German architectural practices, it is necessary to summarize their background. Mennonite families coming from the various provinces to the Low Countries during the 16th and 17th centuries and settling along the Vistula River merged into a religio-cultural unit that retained its characteristics even after adjustment to the new environment, which practices were also continued on the steppes of Russia, the prairies of North America, the Chaco of Paraguay, and the hills of Mexico, whither migrating groups later came. This perpetuated culture was, however, neither purely Dutch nor German but a composite of the two, based on religious principles adhered to for centuries. The peculiar architectural patterns and practices must be viewed against this background.

In the Netherlands the Mennonite influence on architecture has been limited to church buildings, since the residences of Mennonites, both in the country and in towns, show no difference from other Dutch houses. But Mennonite meetinghouses in Holland, at least until about 1840, are quite different from other Protestant church buildings. From the origin of Anabaptism until the end of persecution, i.e., from 1530 to about 1570, Anabaptists and Mennonites did not meet in special meetinghouses, but worshiped where they could gather best, in the open air, in the attic of a warehouse, in a cellar, in a granary, or in other hidden places. About 1570, and in the country somewhat earlier, Mennonites began to assemble in the house of one of the members of the congregation. After persecution had ended, they usually rented a room for worshiping. About 1600 most congregations began to rent or to buy a warehouse or a barn, which was adapted for the meetings only by making small transformations. In the second half of the 17th century nearly every congregation had a meetinghouse of its own. The Flemish congregation at Amsterdam secured its meetinghouse <em>bij't Lam</em> (now Singelkerk) as early as 1608. About the same time the congregations of Rotterdam, Haarlem, Leeuwarden, and Leiden secured their meetinghouses. Before 1795 Mennonites of Holland, like other dissenters, were allowed to worship only in such meetinghouses as had no towers nor bells, so that no one would be "misled" into attending their services, nor were they allowed to be built on street fronts; hence all the Mennonite churches of this period in the towns of Holland are hidden churches (schuilkerken). Good examples of those old hidden churches are today the Mennonite churches of Amsterdam (Singelkerk), Haarlem, and Grouw, Friesland. In the country too the meetinghouses were not allowed to look like churches; mostly they looked like ordinary houses or barns. Especially in the Zaan region of North Holland near Amsterdam many of these barnlike meetinghouses were erected, of which some still existed in the 1950s, e.g., Zaandam-West (built in 1684), Krommenie (1700), Westzaan-Zuid (1731). Typical house-like churches of this period were the meetinghouses of Stroe, on the island Wieringen, which burned down in 1933, the church of Nes on the island of Ameland, those of Zijldijk in Groningen, and the little Menno Simons church at Pingjum, Friesland, restored in 1950. Even a large and important congregation like Harlingen assembled during the 17th and 18th centuries in a barn-like structure called De Blauwe Schuur (the blue barn). In the early 17th century all the churches were very simple and unpainted, and the furniture was also plain. There were no chairs or pews, only benches without backs; no pulpit, but on one side a kind of platform on which the ministers and deacons sat on a bench (later on chairs). There was no heating and the building had only a few small windows, mostly placed rather high in the walls. Sometimes one corner of the meeting place was enclosed as a room for the preachers and deacons to meet in before the service began. This kind of meetinghouse, of which the ground plan was a square, or a rectangle, the square ground form being the oldest, continued to be the normal type for the more conservative Mennonites, such as the Groninger Old Flemish Jan-Jacobsz group, until their congregations were dissolved in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Both Lamists and Zonists permitted more convenience and even some luxury. Their meetinghouses had chairs (for the women) instead of only benches, and a pulpit like that of the Reformed churches. Of this group the former church of Rotterdam (burned down 1940) with its oak boarding and its beautifully carved pulpit was a fine example. The exterior of all those churches was very plain, and stained glass windows, with two or three exceptions, were not permitted. The old country church of Irnsum, Friesland, however, had a small painted window by 1684, and Witveen in 1712 (DB 1872, 34-35). After 1796, when Mennonites obtained full civil rights, no further restrictions were imposed in the building of Mennonite churches. Henceforth the church buildings could be erected on street fronts, and they could have towers, if so desired. Yet towers on Mennonite churches are very rare; some have a little spire or elevation on the facade, like Enschede, IJtens, Joure, Veenwouden, and Oudebildtzijl, the latter having a bell. Only the church of Wageningen (built 1951) had a real tower in the 1950s. About the middle of the 19th century most of the Dutch Mennonite churches were remodeled and many were built new. With a few exceptions they are of no importance in an artistic sense. They are mostly very plain, yet following the artistic ideas of this period by adapting Renaissance porches and Gothic ogival windows. Of higher artistic merit are some churches built in the after 1920. Mennonite churches in Holland usually have a balcony, which is also the location of the choir during the service, if there is a choir. They also have rooms for the meetings of the church board, catechetical classes, etc. All Dutch churches now have organs, introduced generally at the end of the 18th century, the first installed in Utrecht in 1765. Some churches also have beautiful stained glass windows, such as for instance Hilversum and Heerlen. Basements are unknown in Holland. vdZ.

The settlement and building practices of the native Population in the Vistula Delta differed considerably from those introduced by the Dutch Mennonites who established themselves there. Before the arrival of the Dutch Mennonites it was the custom of the natives to settle in compact villages and to build dwelling places, barns, and sheds as separate units. The Mennonites usually located along a river, each on his own land with dwelling place, barn, and shed under one roof, built at right angles with the street. In this long structure the dwelling place was nearest the street; immediately behind it was the barn and finally the shed. More prosperous farmers occasionally attached the shed to the barn in a triangular fashion. At times another section was added to the shed making the total building assume the shape of a cross (Kreuzhof). During the last decades this architectural pattern underwent considerable modification, especially on the larger estates, although the traditional structures could still be found.

Wherever the Mennonites of Prussian background went they took with them their way of life including their architectural traditions, and some of them were preserved in greater purity in isolated settlements in Russia and America than in Prussia. The pattern of the buildings was always the same although different materials were used. In the pioneer stages solid mud walls or adobe brick were used. Later they were replaced by wood or brick. The straw roof was replaced by tiles, tin, or shingles. A deviation from the early Dutch tradition in Prussia was that they settled in compact villages in Russia, and perpetuated the practice in Manitoba, Mexico, and Paraguay. The interior of the house was arranged much as it had been in Prussia and in most of the homes traditional homemade furniture was found.

The dwelling house, always one story, had two entrances, one at the front and one at the rear, each leading into a room serving as a hall (Vorderhaus and Hinterhaus). Between these two halls was a kitchen and in the chimney above it the hams and sausages were smoked. The front hall led into the parlor called Grosse Stube. From the back hall one could reach the two rooms across from the parlor called Kleine Stube and Eckstube. Into these three rooms extended a brick stove which was heated from the kitchen with straw, wood, or dried manure. Between the kitchen and the entrance to the barn were two rooms, the Sommerstube for the boys and the pantry with steps leading into the basement. The attics of the dwelling place and barn were used for storing grain and feed. (See also Furniture in Russia, Mennonite)

The dwelling house and barn were connected either directly by a door or by a short hallway. One side of the barn was arranged for horses and the other for cows. From the barn one entered directly into a large shed where hay, chaff, straw, and possibly machinery were stored. The threshing machine was quite frequently placed in a separate storage room, and the straw outside. The well was located either in the barn or next to the barn door. In addition to implement sheds there were usually a summer kitchen and possibly a small house for the retired parents. The house was usually surrounded by a large yard with many shade trees, an orchard, and well-kept flower and vegetable gardens. Some characteristics such as the predominance of the tulip bed bore evidence of their Dutch background.

When the Mennonites from Russia, in 1874 and the following years, went to the prairie states and provinces of the United States and Canada, they continued their architectural traditions. In the United States, however, they soon discontinued them, accepting the prevailing American practices. Only a very few Mennonite pioneer buildings can be found in the prairie states today. In Manitoba, however, where the more conservative Mennonites settled, they long retained not only the village pattern but also the architectural practices. Although some villages have disappeared and modern buildings are found on farms of the original Mennonite settlement, the old villages and the traditional style of buildings are still represented. Some of the houses are neglected but others are kept in good repair and painted. This is especially the case where more recent immigrants from Russia have taken over the farms of the conservative Mennonites who have moved to Mexico or Paraguay. Most of the buildings are wooden structures surrounded by board or lattice fence. When after World War Ithe conservative Mennonites of Canada moved to Mexico and Paraguay they again transplanted their architectural patterns to an entirely new environment. In Mexico the expected change from the use of adobe or mud to wood has not taken place. One can also detect other instances of conformity and adjustment to the Latin American environment in spite of the extremely conservative attitude of the settlers. The high roofs and the spacious attics have almost completely disappeared and the traditional wooden fences around the yards have been replaced by high adobe fences which constitute an adjustment to the environment and protection against thievery. In general the buildings are smaller here than they were in Canada and Russia.

As has been stated, the later Russo-German architectural pattern in Prussia had originated with the coming of the Dutch Mennonites in the 16th century. Specialists distinguish in the Low Countries between the Frisian, the Saxon, and the Brabant architecture. A comparison of these styles with those in use by the Mennonites leads to the conclusion that the traditional Mennonite pattern must be of Frisian background, but has been somewhat modified during the various adjustments to new environments. It should be kept in mind, however, that the architectural patterns of the Low Countries and northern Germany have much in common and differ radically from those in South Germany and Switzerland (see illustrations).

In church architecture there is considerable similarity between the Pennsylvania-German meetinghouse and that of the Russo-German Mennonites. Both groups originated in strictly Reformed surroundings in which Catholic ritual was abhorred and only plain whitewashed churches were tolerated.

In Northwest Germany one or two of the older buildings of architectural type have been preserved, the one at Norden being a particularly beautiful 18th-century type.

Heubuden Church Building, Exterior and Interior views.

Scans provided by Mennonite Library & Archives, North Newton, Kansas2006-0179 & 2006-0181

Among the Prussian Mennonite rural churches, where the first meetinghouse was that of Thiensdorf erected in 1722, the Heubuden church was typical. It was a large wooden structure extremely plain, with little resemblance to a church building, located in an open field. The main floor was for women and the balcony for men, very much like the Singel Church of Amsterdam. The pulpit was located on the long side with an enclosure for ministers and deacons on either side. A pipe organ was added in the 18th century. Similarly constructed were the churches of Fürstenwerder, Schönsee, Rosenort, and others, A definite Lutheran influence was evidenced in the churches of Elbing, Marienburg, Montane and others which were constructed of brick, and had either steeples or crosses and Gothic or Roman arches. The Danzig Mennonite Church represented an attempt to retain the old pattern with an adjustment to present trends. The early Mennonite churches of Russia bore a striking similarity with those of Prussia, the Chortitza church closely resembling the Heubuden church. During the pioneer days in many settlements, like early Pennsylvania, the same building was used as a school during the week and for worship on Sunday. Perhaps this is the reason why schools and churches were similar in construction for a long time. The typical church structure before World War I was a long brick building rarely with a steeple but with arched windows still revealing the old pattern. The most extreme adjustment to the Russian environment was the Einlage Mennonite Church built in a sort of Russian baroque surrounded by a very heavy brick fence. When in 1874 and after, the Mennonites came to the prairie states and provinces from Russia and Prussia, they continued constructing churches along the traditional lines. The First Mennonite Church of Beatrice, Nebraska; the Hoffnungsau Mennonite Church near Inman, Kansas; the Gnadenberg Mennonite Church near Whitewater, Kansas; and the former Kleine Gemeinde Church near Meade, Kansas, were some of the examples of this tradition. In the process of replacing the old buildings, most of the congregations gradually imitated surrounding practices with little regard to their own principles and traditions. The early Mennonites of Manitoba and Saskatchewan continued to build the traditional plain churches to which they were accustomed in Russia, often using the same buildings also for schools. The Old Colony Mennonites, Sommerfelder, and other groups definitely adhered to a uniform pattern similar to that of Mennonites of Pennsylvania, which they are continuing in Mexico and Paraguay. It is interesting to note that the dwelling places in Mexico are made of adobe while some church buildings are still being constructed of imported lumber, an indication that in the realm of religious practices there is greater reluctance to give up traditions. There are two noticeable extremes among the Mennonites of America regarding church buildings. The ultraconservative groups -- the Amish, Hutterites, and others -- have developed a principle that no special building is to be provided for worship purposes only. They meet in private homes or school buildings. What was originally a necessity has become a basic principle of their faith. The other extreme is that of those Mennonite congregations who, unaware of their principles, accept almost any architectural patterns found in their respective communities. This has produced some very odd mixtures and contradictions like the towers found on many Mennonite churches of the prairies, which are remnants of fortresses of the Middle Ages. When and how did these towers become the adornment of Mennonite churches and what connection is there between them and a church in which the Gospel of redemption and a nonresistant way of life is proclaimed? In conclusion it must be said that Mennonites have not developed more of a specific church architecture than have Methodists, Baptists, or some of the other denominations, and yet there have been certain characteristics peculiar to them. Mennonites of Holland, Prussia, Russia, and the eastern United States have at times developed certain characteristics which express simplicity, honesty, and integration of their basic principles. -- CK1989 Update

In the decades following World War II, North American Mennonites experienced an outburst of church building and institutional construction (colleges, hospitals, retirement and nursing homes, camps, etc.) unprecedented in their history. Construction of church buildings had been postponed by the Great Depression of the 1930s and the war years of the 1940s. After the war, Mennonites found themselves with increased financial resources and ideas for expanded institutional programs. This was accompanied by much residential construction and movement into more urban areas.With radical changes in agriculture, the appearance of Mennonite farmsteads changed. Many special-purpose small farm buildings were torn down as agricultural enterprises became less diversified. With less need for the storage of large quantities of hay, many Mennonite-owned barns fell into disuse and were razed.

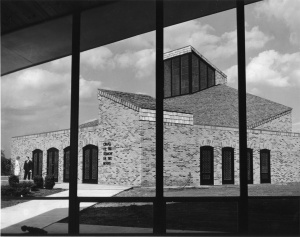

In the 1950s and 1960s many small churches or meetinghouses of simple design were replaced by more spacious and complex church structures. Many of these were built at comparatively low cost with much contributed labor under the direction of local contractors and without benefit of architectural services. Educational wings were often added to existing older church buildings to accommodate expanded church programs.

This period brought to an end the simple "meetinghouse" era. Mennonites were now inclined to borrow architectural ideas from their Protestant neighbors. Often church design reflected the pragmatic decisions of those experienced in building for farm and business purposes. Churches often reflected the "L-shaped" ranch-style residential or pole-shed industrial patterns of the era.

As new church buildings were constructed, a wide range of questions evoked congregational discussion and even conflict. Many of the questions were laden with concerns related to Mennonite traditions and values, i.e., questions of simplicity, wealth, replication of conventional non-Mennonite architecture, expanding church programs, technology, and acculturation. A list of some of these questions follows: How shall the building be identified so that it is recognized as a church? Should it have a steeple, cross, a name on the building, or a free-standing sign? Should it have a central pulpit or a divided chancel? In other words, should the church building be pulpit-centered or chancel-oriented or congregation-oriented? Should the building have plain windows, stained glass windows, a public address system, provision for showing motion pictures, a piano or organ (and where should these musical instruments be located)? Should a loft for a choir be included? Questions about the use of works of art in the church building; choice of furniture, chairs, pews (with or without padded seats), carpeting; and provision for a fellowship hall, a kitchen, even a gymnasium, were raised. Additional issues involved the arrangement of classrooms (for different age groups), the size of the foyer (i.e., provision for visiting before and after services), space for a library, access for those with disabilities, retention or razing of buggy sheds, and landscaping and parking lots (paved or unpaved). Some congregations debated whether to design buildings for multiple use—as day-care centers and for after-school youth activities, etc. Even the decision on location of a new building—whether to move into town or not, a move that might mean leaving behind the historic congregational cemetery—could be controversial.

Significant and varied examples of architect-designed church buildings, which involved substantial dialogue between the architect and the congregation, have appeared. These discussions have focused on some of the above questions, but more importantly, on questions of congregational identity and self-image, heritage motifs, sense of congregational vocation, etc. Several notable examples of such collaboration between architects and congregations are (architect's name in parenthesis) Zion Mennonite Church, Souderton, PA (Edward Sovik); Normal Mennonite Church, Normal, IL (LeRoy Troyer); Bahia Vista Mennonite Church, Sarasota, FL (Orus Eash); and Prince of Peace Chapel, Aspen, Colorado (Ron Birkey).

College and seminary campuses have reflected new architectural patterns and trends. Recent construction of note on Mennonite campuses includes the following: College Church at Goshen College, Indiana (Orus Eash); Mennonite Heritage Centre at Canadian Mennonite Bible College, Winnipeg (Sig Toews); Chapel of the Sermon on the Mount at the Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminaries, Elkhart, Indiana (Charles Stade); Marbeck Center at Bluffton University, Ohio (Jack Hodell); John S. Umble Center, Goshen College (Weldon Pries); Administration Building, Eastern Mennonite University, Harrisonburg, Virginia (LeRoy Troyer).A growing number of Mennonites have been entering the professions of architecture and landscape architecture. More Mennonite congregations are making use of the services of professional architects. This promises to change the face of North American Mennonite church buildings in the years to come.

See also Meetinghouses

Bibliography

Bachman, C. G. The Old Order Amish of Lancaster County. Norristown, 1942.

Francis, E. K. "The Mennonite Farmhouse in Manitoba," Mennonite Quarterly Review 28 (1954): 56-59.

Gallee, J. H. Das niederländische Bauernhaus und seine Bewohner. Utrecht, 2 v. 1908-09, one vol. text, one vol. illustrations.

Krahn, Cornelius. "The ethnic origin of the Mennonites from Russia." Mennonite Life 3 (1948): 45.

Ludwig, G. M. The influence of the Pennsylvania Dutch in the Middle West. Pennsylvania German Folklore Society, 1947.

The Mennonite community (January 1950).

Montgomery, R. S. Home craft course in Pennsylvania-German architecture. Plymouth Meeting, 1945.

Schowalter, P. "Mennonite Churches in South Germany." Mennonite life 7 (January 1952).

Schowalter, P. "Die Kirchen der Mennoniten in Pfalz-Hessen." Mennonitisches Jahrbuch (1952)

Smith, C. Henry. The Mennonite Immigration to Pennsylvania. Norristown, 1929.

Stoudt, J. J. Pennsylvania Folk-art. Allentown, 1948.

Weaver, M. G. Mennonite of Lancaster Conference. Scottdale, 1931.

Wenger, J. C. History of the Mennonites of the Franconia Conference. Telford, 1937.

Wiebe, H. Das Siedlungswerk niederländischer Mennoniten im Weichseltal zwischen Fordon und Weissenberg b. z. Ausgang des 18. Jahrhundert. Marburg a.d. Lahn, 1952.

Wittlinger, Carlton O. Quest for Piety and Obedience: The Story of the Brethren in Christ. Nappanee, IN: Evangel Press, 1978: 492-495.

| Author(s) | Cornelius, Nanne van der Zijpp Krahn |

|---|---|

| Robert S. Kreider | |

| Date Published | 1989 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Krahn, Cornelius, Nanne van der Zijpp and Robert S. Kreider. "Architecture." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1989. Web. 25 Nov 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Architecture&oldid=74907.

APA style

Krahn, Cornelius, Nanne van der Zijpp and Robert S. Kreider. (1989). Architecture. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 25 November 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Architecture&oldid=74907.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, pp. 146-151; v. 5, pp. 34-35. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.