Europe

This article was written in the mid-1950s.

Introduction

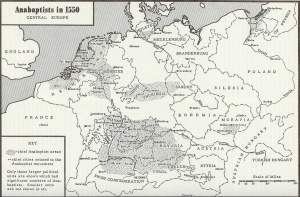

It must be said at the outset that in spite of basic unity on all major points of faith and life (barring the revolutionary and radical fringe elements) the Anabaptist-Mennonite movement in Europe has never been a fully unified movement or church. Politic-cultural and language barriers, among other things, have prevented this. Apart from a very small French movement in French Flanders and an elusive English movement, the Anabaptist movement was wholly Teutonic, but composed of two German-speaking parts and one Dutch-speaking part: (1) the Swiss-South German founded in 1525, (2) the Hutterite group in Moravia founded in 1528, essentially the communistic wing of the first group, and (3) the Dutch-speaking Dutch-North German-West Prussian group, begun in 1530 (there was also for a time a Middle German-Middle Rhine branch of the Swiss-South German group, but this did not survive the first half-century). The rapid spread of the movement is most remarkable. Beginning in January 1525 in Zürich, by 1535 the entire Teutonic block of Western Europe had been covered. An approximate circumference line would run Chur, Gratz, Brno, Königsberg, Leeuwarden, Ypres, Strasbourg, Basel, Chur.

This article will trace the general history of the above three groups from an over-all European perspective, leaving the detailed story for the national articles—Austria, Belgium, England, France, Germany, Moravia, Netherlands, Poland, Russia, Switzerland, and for other articles on provinces and regions.

1525-1648: General Anabaptist History and Group Interrelations

From the beginning Anabaptism was a proscribed movement, with the imperial mandate of 1529 (Speyer) calling for universal extermination. Apart from early transient and partial toleration at a few places such as Strasbourg and Nikolsburg, and the general toleration in Moravia by the nobility until the Jesuit reaction began its deadly work (1592), to be an Anabaptist was to be a criminal subject to arrest, torture, imprisonment, exile, confiscation of property, and in most larger territories (except Hesse) execution. In the first ten years, 1525-35, several thousand were executed, and before the last execution (Zürich, Switzerland, 1614, the Netherlands 1574, Belgium 1594) there must have been at least 5,000 martyrs. The Hutterite chronicle as of 1540 lists 2,147 brothers and sisters who gave their life for their faith, and van Braght's Martyrs' Mirror (1660) lists 2,500. The Mennonite Encyclopedia has name articles for over 2,000 martyrs. Toleration came first in Holland, about 1572, though not complete at once, and by 1600 the period of severe persecution was really past in that country. In Switzerland severe persecution continued (canton of Bern) until the middle of the 18th century, and real toleration did not come until 1815. For the Hutterites heavy persecution (after the initial decade or two) really set in only with their expulsion from Moravia in 1592, but continued until the last remnant found refuge in Russia in 1770. In Austria, Tyrol, Bavaria, the rest of South Germany, and Middle Germany (Saxony, Thuringia, Hesse, Cologne) persecution did not cease until the movement was totally destroyed (ca. 1580-1600). By the time of the Thirty Years' War (1618-48) all Anabaptist remnants had vanished in the South and in Middle Germany, except for small remnants in the cantons of Bern (Emmental and Thun) and Zürich (Horgen) and the struggling Hutterite communities in Hungary. The once promising Westphalian Anabaptist communities were finally suppressed by the Counter Reformation. On the other hand the movement in the Dutch language area was growing at that time almost everywhere: the Netherlands, Lower Rhine, East Friesland, Schleswig-Holstein, and Altona (the latter two settlements founded by refugee immigration 1600-50) except in Catholic Flanders where it had been wiped out by 1630, and in a few areas where it still had a severe struggle. Likewise the important settlements in the Vistula Delta area (Danzig-Elbing, Culm-Thorn, Königsberg), which had been founded by Dutch refugees 1535-60, were rapidly developing into a major block. The Swiss, Hutterites, and West Prussians (except the Danzig, Elbing, and Königsberg city groups) were all rural and destined to remain so almost exclusively throughout their history, including their daughter settlements. By contrast the Lower Rhine, most Northwest German congregations, and all the Dutch Mennonites (except certain rural areas in Groningen, Friesland, and North Holland) were solidly urban, already manifesting some of the industrial and commercial enterprise which was later to be so characteristic of these groups. Only in the Netherlands, because of relatively early toleration, their large number, and their urban character, were Mennonites entering into the national cultural life, although this came also in Krefeld, Emden, Hamburg, and Danzig in the next century. Here in the Netherlands the Mennonites made a real and significant contribution (1600-1700) in art and literature (Golden Age) as well as in medicine; they also were often leaders in trade and banking, navigation, and whale fishing.

During this period the three major groups listed earlier remained relatively distinct, with little intergroup contact. The Hutterites viewed the Swiss, Dutch, and Prussians as lacking true Christian principles in not adopting the communal way of life, and at times indulged in vigorous polemics against them, although on at least one occasion (Frankenthal, 1571) they joined with the Swiss in a disputation against the state church leaders. The language barrier kept the Swiss-South Germans and Dutch apart. Menno Simons was not translated into German until 1575, and then only the Foundation-Book. A "short Menno" appeared in 1754, but Menno's complete works were never translated in Europe. Dirk Philips was translated into German in part in 1611, but no other Dutch Mennonite writings at all until the next period.

An attempt to draw the Swiss and Dutch closer together in the mid-16th century was frustrated by the intransigence of the Dutch (Wismar articles of 1554 and Menno's writings against Zylis and Lemke of 1559) on the two points of shunning and Menno's peculiar doctrine of the Incarnation, neither of which the Swiss could accept (Strasbourg conferences of 1555 and 1557). The Dutch actually put the Swiss under the ban about this time. Only a century later (1660 ff.) when the severe need of the persecuted Swiss touched the brotherly love of the Dutch, and the latter had somewhat relaxed their severity, did the situation change. There was a High German group (Swiss-South German refugees and influence in the region of Cologne) who came into closer fellowship with certain Dutch elements and actually joined in several Dutch "unity" confessions of faith. (Concept of Cologne in 1591, High German confession of Jan Cents in 1630, Dordrecht Confession in 1632).

During this period the relations of the Dutch with the North German and Vistula congregations were very close. The latter were composed largely of refugees from the Netherlands (Friesland) and Flanders, and maintained the Dutch language in family and church life (first German preaching in Hamburg 1786, in Danzig 1760s, and first German publication a 1660 confession of faith at Danzig). During this period and for another hundred years Amsterdam remained the mother of the eastern churches in more ways than one.

At the end of this period the distribution of Mennonite population (including children) might have been as follows: the Netherlands (including East Friesland and Lower Rhine) 140,000; Switzerland 1,000; Schleswig Holstein-Hamburg 1,500; Vistula Delta and Königsberg 5,000; Hutterites 5,000; a total of over 150,000. Without unbaptized children the baptized members hardly exceeded 75,000. (No list of congregations, ministers, or members is available at all before the Dutch Naamlijst of 1731, and no thorough statistics until the late 19th century. Congregations in Germany were not on this list in the Naamlijst before 1766.)

During this period the original Anabaptist heritage of faith and life was maintained relatively intact. There was a loss of the sense of mission and consequent development of introversion, but the original concept of the church as a brotherhood of believers separated from the world and maintained pure by discipline was staunchly maintained, together with nonconformity to the world, nonresistance, nonswearing of oaths, simplicity of costume and manner of life. Theologically the only minor changes were those due to Socinian and Collegiant influences in the Netherlands. The serious major divisions (1565-80) in the Netherlands and in the North German and Vistula congregations persisted, particularly the Flemish and Frisian (the Waterlander in Holland only). Mennonite literature flourished in the Netherlands, but nowhere else. Hans de Ries, P. J. Twisck, Lubbert Gerritsz, and J. P. Schabalje ranked with the best in Dutch Christian literature, and the Mennonite Biestkens Bible had reached a peak of popularity with over 100 editions of the whole Bible or New Testament in 1560-1648. The Swiss had their Ausbund hymnbook and Froschauer Bible (not originally Mennonite) reprints, but little else. The Hutterites had their extraordinary manuscript chronicles, epistles, theological treatises, and confessions, but only two printed books, Riedemann's Rechenschaft of 1545 and Ehrenpreis' Sendbrief of 1652.

1648-1918: Developments

This period witnessed a series of migrations of prime significance. From 1650 to 1750 a considerable number of Swiss (from Zürich and Bern) migrated to Alsace, the Palatinate, and Baden, and after 1709 to Pennsylvania (joined by numerous Palatine immigrants), with a smaller contingent settling in Groningen in Holland, and another group transferring from inner Bern to the Jura territory and Basel. Emigration from the Netherlands ceased altogether, except for the tiny group of 1853 from Balk to Indiana, which is now extinct. There are no Dutch Mennonite colonies; in fact the Dutch Mennonite population declined so greatly (to 30,000 by 1800) as to forebode extinction. A few of Dutch extraction came to Pennsylvania 1683-1710 from the Lower Rhine region and Hamburg. A small group of Palatines and Alsatians also settled in Galicia 1780ff.

But the major migration was from the overcrowded, restricted Vistula Delta region, whence in 1788-1840 some 10,000 souls went to the Ukraine (a few in 1853 to Samara) to establish the great Mennonite body in Russia, which by 1914 had reached 100,000 souls with some 30 distinct settlements, including the Caucasus, Crimea, Volga area, Orenburg, and Ufa, Western Siberia, and Turkestan. This growth was in spite of the loss of one third of the Russian Mennonite population (18,000) by emigration to the prairie states and provinces of the United States and Canada in 1873-80. Smaller settlements of Vistula Mennonites had also been made in inner Poland (near Warsaw) and Volhynia (both Russian after the Congress of Vienna in 1815).

Another notable migration was the post-Napoleonic (1817-50) emigration of several thousand Swiss, Alsatian, and South German (also some Galician and Hessian) Mennonites to the North Central States (western Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois), Iowa, and Ontario.

In this period there were two serious divisions with permanent consequences. The first was the Amish schism of 1693-97, which permanently split the Swiss-South German group in half, and which is still perpetuated in North America though now fully overcome in Europe. The second was the Mennonite Brethren schism in the Ukraine in 1860 ff., which ultimately won about one fourth of the Russian Mennonites (25,000 souls in Russia by 1914) and has been perpetuated in North and South America. The smaller divisions include the immersionist Dompelaers in Hamburg 1648, extinct by 1676; the Kleine Gemeinde in the Ukraine in 1812, with its sub-schism of 1862 the Krimmer Mennonite Brethren, both perpetuated exclusively in North America as very small groups; the further small Russian divisions, now practically all extinct, the Jerusalemsfreunde (1866), the Apostolic Brethren (Brotbrecher) (1890), Allianzgemeinde (1905); and the Hahnische Mennonites in Baden in 1868, still existing there in three small congregations. Also to be noted is the Neu-Täufer division of 1835 in the Emmental (half from the Reformed Church, also called Fröhlichianer after their leader Samuel Fröhlich) existing today in moderate numbers both in central Europe (Switzerland and South Germany), where they are called Evangelische Taufgesinnte, and in the central United States, where they are called Apostolic Christians. The older Dutch divisions were completely healed, together with the newer division of Lamists vs. Zonists (1664-1801) in the Algemene Doopsgezinde Sociëteit (General Mennonite Conference) of 1811, although the Flemish-Frisian division persisted in superficial form in West Prussia and Russia until into the 20th century.

The first century of this period was marked by the closest relations that have ever developed between the Dutch and Swiss-South German groups. The severe persecution by the Bernese government brought vigorous though ineffective political intervention by the Dutch Mennonites, while the physical suffering of the Swiss and the Palatines in this time brought generous financial aid from the Dutch for a very long period of time (1650-1750) through the noted Commission for Foreign Needs. This commission helped also in emigration, assisting some Swiss to settle permanently in Groningen (1710 ff.), where they have been completely assimilated, and many more Swiss and Palatines to emigrate to Pennsylvania 1710-50. A similar attempt to resettle Tilsit-Memel Mennonites in Holland (1732) miscarried.

During this first century of the period also the relations between the Netherlands, North Germany, and West Prussia remained close, even down to Napoleonic times, with considerable translation of Dutch Mennonite literature into German (confessions, catechism, sermons), as well as the maintenance of the Dutch language in preaching until late in the 18th century. Later with the rise of nationalism, particularly in Germany with the rise of Prussia and the formation of the German Empire in 1871, international relationships among European Mennonites declined noticeably, except between the West Prussians and the Russians and the Dutch and Northwest Germans. Alsace-Lorraine being a part of Germany 1870-1918, the French Mennonites were badly divided during this time, but the Alsatian Mennonites at the same time were strongly oriented toward the South Germans, especially the Baden group. The growing sense of German unity in turn finally overcame the century-old distance between the Northwest Germans, the West Prussians, and the South Germans, though slowly. The Mennonitische Blätter, founded in 1854 as an all-German periodical, the first Mennonite church paper in Europe and the only one for another generation (Gemeindeblatt, Baden 1870; Zondagsbode, Netherlands 1887; Zionspilger, Switzerland 1882; Mennonitisches Gemeindeblatt, Galicia 1912; Botschafter, Russia 1905-14; Unser Blatt, Russia 1922-26; Friedensstimme, a private venture in Russia, 1905). The attempted Vereinigung of Mennonite Churches in Germany (1886- ) was only partly successful, since most of the West Prussians, all of the Badischer Verband, and part of the Palatinate-Hesse churches stayed outside.

A serious twofold block to closer fellowship between the Dutch Mennonites and the remaining Mennonites of Europe during this period was the differing theological and ecclesiastical development as between the Netherlands and the rest of Europe. Liberal theology came into the Dutch churches in the second half of the 19th century and by 1870 had nearly completely captured Dutch Mennonitism, together with East Friesland and Krefeld. Along with this came the surrender of nonresistance and nonconformity rather completely, as well as a complete shift from a lay ministry to a trained and salaried ministry (this latter change had begun already in 1735 with the founding of the seminary at Amsterdam). Everywhere else in Europe, except in the German city churches where liberalism also made inroads in the 20th century, the chief new influence was pietistic. The West Prussian, South German, Swiss, French, and Russian churches either remained traditional and relatively inert, or became pietistic (especially Hamburg, Palatinate, Baden). These groups also retained nonresistance longer (Germans fully to 1870 and partly to 1914, Russians to the end, Swiss partly to the present time, French not after 1815), also a degree of nonconformity combined with a rural culture, and (except in the German city churches and the Palatinate) kept the lay ministry. Pietism also found an echo in the Netherlands in the 18th century (J. Deknatel of Amsterdam) and later a similar influence, the Reveil (Isaac da Costa of Amsterdam) in the 19th century.

At the same time, in the course of the 19th and 20th centuries all the European Mennonite groups (the Swiss last, and the Russians scarcely at all since they developed their own German-Mennonite culture) became increasingly nationalized and assimilated into their national life and culture, losing largely their sense of separation and acquiring a political interest. Particularly was this the case in the urban groups. Ernst Crous has vividly described this process in Germany in his essay, "How the Mennonites of Germany Grew to Be a Part of the Nation." No Dutch Mennonite would have thought of writing such a comparable essay for the Netherlands, because that assimilation had taken place two centuries earlier and the Dutch Mennonites occupied in a sense an elite status in Holland. And in Russia the Mennonites were proud to have remained distinct from the Slavic culture of the nation as an autonomous German-Mennonite culture group; those Russian Mennonites who became interested in a rapprochement with the Russian culture were usually under suspicion and often criticized.

It is remarkable that only the Russian Mennonites developed their own church educational program (they in a sense had to, of course, to survive). The Dutch vigorously object to church schools even today, and have never developed a full school of any sort, not even a full theological faculty. The attempt at a German Mennonite high school at Weierhof in the Palatinate (1805 ff.), while educationally successful was a relative failure as a church school because of the small Mennonite patronage. A weak and late attempt in West Prussia died in birth, although there had been some elementary schools in certain West Prussian communities in the 17th-19th centuries. The German-speaking Jura Mennonites, living as a German-language island in a French culture area, have maintained a series of Mennonite elementary schools for a century, latterly with state financial aid.

The 19th century was marked also by a noteworthy development of the regional conference system, Switzerland 1780, Dutch Algemeene Doopsgezinde Sociëteit 1811, West Prussia 1830, Baden 1848, Palatinate-Hessen 1870, South German 1884, Mennonite Brethren in Russia 1876, Mennonite Church in Russia 1880, Alsace 1905, French-speaking 1905. While the autonomy of the local congregation was largely retained (except in the Badischer Verband where the conference had complete centralized control over the local churches) the conference inevitably began to influence the local churches toward more uniformity and more alertness and activity.

A noteworthy development in the 19th century was the rise of foreign mission interest, although home missions and evangelism remained either totally undeveloped or quite rudimentary. Through Baptist influence the foreign mission cause came to be supported in the Palatinate (1820 ff.), in Holland (1830 ff.), and in West Prussia (1830 ff.). When the Dutch Mennonite mission board was organized in 1847 (work in Java began in 1851) it found considerable support in West Prussia and Hamburg, also some in the Palatinate, and in South Russia whence it drew much of its support and most of its few missionaries until 1914.

Except for the Netherlands there was a remarkable paucity of Mennonite literature in Europe throughout this period. This might be expected from the largely uneducated and rural groups such as Switzerland, France, Baden, and West Prussia. Even in the German city churches with their trained ministers little was produced, except in Hamburg and Emden. The same is true for the Palatinate. Even in Russia the literary output was noticeably small down to the very last. Perhaps the Mennonites were too much assimilated to other thinking, some to Pietism, some (the trained clergy) to the current liberal or orthodox theology of the main trends in European life. In some cases of course the constituency was too small to support the publication of literature. In Russia preoccupation with the problem of colonization no doubt played a role. Dutch Mennonites published relatively much all through this period. Four major Mennonite areas developed their own hymnbooks, confessions, and catechisms: Holland, West Prussia, Russia, and South Germany, but no church publishing house ever developed among the Mennonites of Russia. Mennonite population remained relatively static in Germany, France, and Switzerland during the 19th and 20th centuries, doubled in the Netherlands 1815-1918, and multiplied tenfold in Russia.

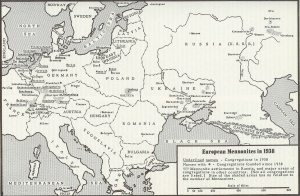

1918-56: Developments since World War I

The two serious world wars (1914-18 and 1939-45), together with the rise of Communism in Russia, have had decisive effects on Mennonitism in Europe. The repeated German attacks on France in 1870, 1914, and 1940 seriously alienated the French and Swiss Mennonites from the Germans, though brotherly good will has in part overcome this. The rise and temporary rule of Nazism (1933-45) together with the German attack on the Netherlands caused even more serious alienation between the Dutch and the Germans. World War I between Germany and Russia brought a serious strain on the German-oriented Mennonites in Russia. The defeat of Germany in 1918 returned Alsace to France but ruptured the growing fellowship of Alsatians and Germans. The defeat of Germany in 1945 resulted in the destruction of the age-old Mennonite settlements in inner Poland and Galicia, also making the condition of the German-speaking Mennonites in Russia almost intolerable. About 35,000 Russian Mennonites, mostly of the Chortitza settlement, were able to escape in 1943-45 with the retreating German army and some 12,000 were ultimately resettled in Paraguay and Canada, the rest being recaptured and returned forcibly to Russia.

However, the most important development in this period was the practical destruction of Mennonitism in Russia as a consequence of the Russian Revolution and the establishment of atheistic communism as the ruling force in Soviet Russia. The Mennonites did not revolt by force against this development, but being unable spiritually to accept it, they resisted communization. This made them de facto enemies of the Communist state, and Stalin's measures to liquidate the peasant resistance to collectivization in 1927-34 hit the Mennonites very hard. Had it not been for the decision of some 21,000 to emigrate to Canada (1922-25), partly because of the great famine and disorder of 1918-20, and the escape of some 4,000 in 1929-30, the losses would have been still greater. Statistics are impossible, but it is clear that most of the Mennonite settlements in Russia no longer exist, at least with any large number of Mennonite families. Mennonite church life became practically extinct in that land by 1935, although there was sufficient private and family religion left to make possible a brief reinstitution of church life in the Ukraine in 1941-43, especially in Chortitza during the German occupation. The Siberian settlements suffered the least, and there was actually a new settlement established on the Manchurian Amur border 1926-30, which, however, was almost extinguished, largely by mass flight, in 1930-31.

Noteworthy developments have taken place in inter-Mennonite relations since 1918. One is the Mennonite World Conference, held in Basel in 1925, Danzig in 1930, Amsterdam in 1936, Goshen and Newton (United States) in 1948, Basel again in 1952. Another was the great relief work in the Russian famine (1920-22) largely by the American Mennonites, but also in part by Dutch Mennonites. (German Mennonites cared for several hundred who were stranded for a time in Germany, e.g., at Lechfeld and in Mecklenburg.) A third was the extensive relief work of the American Mennonites (Mennonite Central Committee) in Western Europe, including all Mennonite areas except Russia, 1945- .

Finally mention must be made of the highly significant migrations of Russian Mennonites to Canada (1) in 1922-25 and 1930, and (2) 1947-52 which have vitally affected Canadian Mennonitism, and the similar substantial Russian settlements in 1930-32 in Brazil and Paraguay, also in 1947-50 in Paraguay again. The last movement of migration was of small groups of Danzig-West Prussian Mennonites to Uruguay 1950-52 and a few to Canada.

One of the historic tragedies of Mennonite history, though not as extensive as the tribulation and suppression in Russia, was the total destruction of the 400-year-old Mennonite community in West Prussia-Danzig in 1945 as a result of the German defeat by Russia and the Polish reoccupation of the Vistula Delta (Russia taking over the Königsberg corner). About three fourths (9,000) of the West Prussians survived as refugees and are now relocated as follows: 1,000 in Uruguay, 300 in Canada, 8,000 in West Germany, with a rather compact block of about 1,000 in the Palatinate.

A theological trend worth noting since 1910 is the substantial decline of liberalism in Holland and Northwest Germany during this period, paralleling the decline of liberalism in European Protestantism in general, and the resurgence of an evangelical theological emphasis.

The 1950 distribution of Mennonite baptized membership in Europe was as follows: Netherlands 41,000, Germany 8,000, France 3,000, Switzerland 1,500, total (without Russia) 53,500.

Bibliography

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. I, 614 f.

| Author(s) | Harold S Bender |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1956 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Bender, Harold S. "Europe." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1956. Web. 2 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Europe&oldid=113349.

APA style

Bender, Harold S. (1956). Europe. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 2 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Europe&oldid=113349.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, pp. 255-261. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.