Difference between revisions of "Chortitza Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m (Added category.) |

|||

| Line 270: | Line 270: | ||

Stumpp, Karl. <em>Bericht über das Gebiet Chortitza . . .</em> . Berlin, 1943. | Stumpp, Karl. <em>Bericht über das Gebiet Chortitza . . .</em> . Berlin, 1943. | ||

{{GAMEO_footer|hp=Vol. 1, pp. 569-574|date=1955|a1_last=Bergmann|a1_first=Cornelius|a2_last=Krahn|a2_first=Cornelius}} | {{GAMEO_footer|hp=Vol. 1, pp. 569-574|date=1955|a1_last=Bergmann|a1_first=Cornelius|a2_last=Krahn|a2_first=Cornelius}} | ||

| + | [[Category:Mennonite Settlements in Russia]] | ||

Revision as of 20:28, 14 July 2016

Introduction

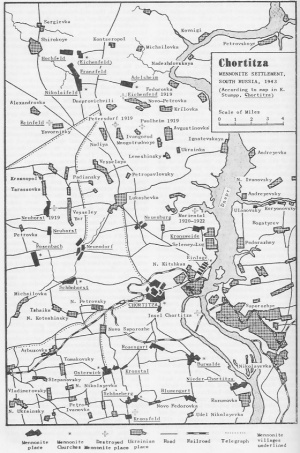

Chortitza (Khortitsa) Mennonite Settlement (also known as the Old Colony or Alt-Kolonie in German) was located on the left bank of the Dnieper River between the cities of Ekaterinoslav (Dnepropetrovsk) and Alexandrovsk (Zaporizhia) in the Ukraine, Russia. This was the first Mennonite settlement in Russia, established in 1789. The settlers came from the Danzig area upon invitation by Catherine II. The object of the Russian government was to have the border regions settled by a stable agricultural population. It sent representatives into foreign countries (Germany and Bulgaria) to examine and secure suitable immigrants. The attention of the government was probably directed to the Mennonites by the Lutheran pastor of Nassenhuben near Danzig, Joh. Reinh. Forster (d. 1769 at Dirschau, West Prussia), who at the request of Catherine traveled through Russia in the 1760s, especially visiting the (non-Mennonite) settlements in the province of Samara.

The Beginning

The general economic conditions in Germany, and particularly the position of the Mennonites in the regions of West Prussia after the annexation of Poland, had produced a feeling of anxiety among the Mennonites, so that the first invitation of the Russian commissioner Trappe to the elders of the Danzig churches in 1786 was received with great reserve in order not to antagonize the Danzig city council, though 60 families were found willing to emigrate. According to Mennonite tradition two deputies, Jakob Höppner of Nehrung and Johann Bartsch of Danzig, were appointed by the congregations and sent to Russia to inspect the land and draw up the necessary agreements. Supported by Trappe and the Russian consulate in Danzig the delegates undertook their journey in 1787. After a conference with Catherine II (13 May 1787) and the proper authorities, and after defining their rights and duties along economic and especially religious lines (apportioning of land, support, tax-free years, self-government, free exercise of religion) to the satisfaction of all concerned, they returned in the same year. Meanwhile Trappe had secured information about the attitudes and manner of life of the Mennonites in Holland, and when the Danzig authorities expressed their displeasure with his plans, he went temporarily to Marienwerder. Since he was able to meet the peculiarities and wishes of the Mennonites with understanding, he soon won further confidence. The return of the deputies and the imminent edict of Friedrich Wilhelm II of 1789 caused the mood already present to mature to a quick decision, with the result that in spite of the continued aloofness of the elders a greatly increased number of families declared themselves willing to emigrate when negotiations were resumed in 1788, and with or without the consent of the Danzig authorities applied to the Russian consulate for passports.

In the fall of 1788 two groups of emigrants were organized, numbering 228 families, who spent the winter in Dubrovna in the province of Mogilev. In 1797 a second train of 118 families followed; several families had meanwhile decided to join the first party, thus about 400 emigrant families became the basis of the settlement. In 1819 the settlement consisted of 560 families with 2,888 souls, in 1910 about 2,000 families with about 12,000 souls. The increase in population was at first 5 per cent annually.

Villages of the Chortitza Settlement: Mennonite Villages, Population, Exile, Evacuation, 1789-1941

| Number | Village | Year of Founding |

Population in 1914/18 |

Killed in 1919 |

Exiled in 1929-41 |

Evacuated in 1941 |

Total Exiled and Evacuated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chortitza | 1789 | 2,861 | 13 | 327 | 187 | 514 |

| 2 | Adelsheim | 1869 | 334 | 4 | 21 | 11 | 32 |

| 3 | Einlage | 1790 | 600 | 9 | 245 | 23 | 268 |

| 4 | Franzfeld | 1869 | 466 | 11 | 85 | 24 | 109 |

| 5 | Hochfeld | 1869 | 313 | 19 | 53 | 12 | 65 |

| 6 | Kronsweide | 1789 | 408 | 13 | 13 | 0 | 13 |

| 7 | Nikolaifeld | 1869 | 221 | 13 | 113 | 4 | 117 |

| 8 | Neuendorf | 1790 | 1,050 | 13 | 123 | 39 | 162 |

| 9 | Neuhorst | 1790 | 315 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| 10 | Neuenburg | 1789 | 280 | 7 | 17 | 11 | 28 |

| 11 | Rosenbach | 1928/29 | NA | NA | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| 12 | Schönhorst | 1790 | 689 | 4 | 51 | 15 | 66 |

| 13 | Blumengart | 1824 | 213 | 3 | 37 | 7 | 44 |

| 14 | Burwalde | 1803 | 536 | 7 | 72 | 8 | 80 |

| 15 | Osterwick | 1822 | 1,550 | 3 | 81 | 136 | 217 |

| 16 | Rosengart | 1824 | 260 | 0 | 14 | 51 | 65 |

| 17 | Nieder-Chortitza | 1803 | 835 | 21 | 83 | 276 | 359 |

| 18 | Schöneberg | 1816 | 275 | 1 | 43 | 10 | 53 |

| 19 | Kronstal | 1809 | 460 | 1 | 70 | 13 | 83 |

| Total | 11,666 | 144 | 1,456 | 831 | 2,287 |

Source: K. Stumpp, Bericht über das Gebiet Chortitza.

Economic Progress

At first the settlers were divided into 15 villages; by 1824 three others had been established to provide for the surplus of population. The government at first assigned 89,100 acres, but increase in population and prosperity caused the colony management early to acquire land for daughter colonies (about 190,000 acres). With the increasing prosperity several groups settled on land they had themselves acquired (about 108,000 acres), bringing the ultimate total of the land belonging to the Chortitza settlement to about 405,000 acres, not including rented land and privately owned estates.

Vocationally the first settlers were craftsmen and small manufacturers. In 1819, thirty years after the founding, 300 manual craftsmen could still make a living; their products were used not only in the agricultural growth of the colony, but also outside. They also farmed as a sideline. Domestic industry was in general limited to wool spinning (1819, 557 spinning wheels) and weaving (49 looms), for many of the immigrants had been weavers in Danzig. The land apportioned to them could not all be cultivated yet, and was therefore used in profitable sheep grazing. Not until later did agriculture displace these sidelines. By 1819 the nearly treeless tract had been planted with 30,000 fruit trees, 35,000 other trees, 1,000 grapevines, and about 25,000 mulberry trees, since the silk industry after 1810 had become a lucrative side line (according to Reisswitz and Wadzek). In the 1830s and 1840s these beginnings were greatly stimulated under the leadership of Johann Cornies, the representative of the government in the colonies, who was himself a resident of the Molotschna settlement. Not until after the 1860s did agriculture move into the foreground and lead to the manufacturing of agricultural machinery, the importance of which extended far beyond the Mennonite settlements, and which continued to grow until World War I. The settlement passed through the regular steps of colonization, determined by the quality of the settlers and by the slow adaptation to new economic conditions: from the repetition of customary practices, to the proper exploitation of the soil by a more adventurous spirit, and finally to the integration in the total national economic pattern. These three steps are represented by (1) the years of settlement, (2) 1820-60, and (3) 1860-1917 The solicitude of the government is clearly discernible throughout the first two periods, in spite of many unfaithful and inexpert officials. It did not withdraw until after the liberation of the Russian peasants (1861), when the development had taken its sure and proper course and government aid was no longer needed.

The rapid industrialization of Europe toward the middle of the 19th century and the increasing demand for grain laid the foundation for the expansion of grain farming on the Russian steppes. The Mennonites of Chortitza were leaders in agricultural improvement, in the discovery of the most suitable variety of grain, and in the production of agricultural machinery. Peter Lepp founded the first factory in Chortitza in 1853. In 1888 there were eight such factories, and in 1907 there were sixteen. Plows, drills, wagons, mowers, threshing machines, fanning mills, and steam engines produced by Mennonites found ready acceptance also among the Russian population. Some of the outstanding Mennonite factories were Hildebrandt and Pries, Lepp and Wallmann, and A. Koop and Company. As a result of the increased grain production an expanding grain and milling industry developed. One of the largest concerns was Niebuhr and Company. Starch factories, brickyards, and other industries followed. Chortitza and Alexandrovsk were the centers for these industries.

Leadership

Development in spiritual matters ran a far more complicated course and must be considered more dependent on the will of the leaders and their relation to those they were leading. The original immigrants had two characteristics -- outward poverty and defective insight, to say nothing of the division into Frisian and Flemish congregations (Danzig, Neugarten, Marienwerder). The Russian government was interested in having a homogeneous church; therefore Trappe sought to form a single brotherhood with the support of the Dutch Mennonites. But the conference of elders on 28 June 1788 in Rosenort (Elbing) found among the emigrants no competent personality agreeable to both sides, so that the emigrants went to their new foreign home without a church organization. Undesirable consequences were already evident in their winter quarters; want of worship services interrupted their traditional life. The election of two readers for divine services was of no avail. The request to the mother church for the ordination of a minister was only tardily granted when they had already settled. The inadequacies of the early period, the death of the first elder they chose and ordained by letter, Bernhard Penner (d. 1791), and the strife concerning his successor, friction between the deputies who had charge of temporal government and the ministers, who by tradition were the "rulers," and finally calling on the government authorities in the dispute, created an unedifying situation and split the church into two camps, so that the quarrel could be settled only by strictly impartial judges. The groups appealed again to the mother church in Prussia, which sent the elders Cornelius Regier of Heubuden and Cornelius Warkentin of Rosenort (Elbing) to settle the dispute; this was accomplished with great effort and self-sacrifice. Church matters in the Flemish congregation (Chortitza) as well as the Frisian congregation (Kronsweide) were adjusted, elders and ministers were chosen and ordained, and a tolerable relationship established. Elder Cornelius Regier died in Chortitza on this journey (1794); his work was finished by his younger colleague Warkentin. But a union of the two congregations, as desired by the government, did not occur.

The division of jurisdiction as between the deputies (Höppner and Bartsch) and the ministers did not eliminate friction, and strife flared up periodically, which even led to the excommunication and imprisonment of Höppner. The fault cannot now be ascertained, but probably lay chiefly in jurisdictional disputes, for temporal and spiritual authority were in some instances hard to separate and were even later not entirely separated. Friction of this kind also arose in the period of Johann Cornies' work, who, as a member of the directorate of the Agricultural Association formed in 1832, planned larger organizations that he could carry out only by the support of the collective church. Since the representatives of the church were at the same time personally involved, they sometimes concealed their likes and dislikes behind the church or religious ideology and distorted the facts. In the conflict between the Chortitza churches and the Agricultural Association, the jurisdiction of the church was limited; but the church thereby merely lost a source of friction as also in the assignment of jurisdiction to temporal village authority.

Education

An additional source of friction arose from the assignment of school supervision to the Agricultural Association, thus forming the basis for the school council. After the colony was really established, much thought was given to the care of schools. Nevertheless, following the example of the home community in West Prussia, the schools were limited to a very narrow scope of instruction -- reading, writing, arithmetic, and Bible and catechism. This was the extent and the content. Teachers were haphazardly assigned. These inadequate conditions, which the supervisory assembly could not change, remained until the founding of the Chortitza Zentralschule in 1842 in the village of Chortitza. The new school was to provide further education and also serve as a normal school for teachers. Idealistic and farsighted men as teachers and members of the board (H. Heese, G. H. Epp, J. Janzen, A. Neufeld) gave the school the character of a German educational institution and furnished the teachers for the village schools. Science, languages, mathematics, etc., were under the supervision of the school board, and religion under the representatives of the church. In 1871, when the Agricultural Association was dissolved, the school board also lost its authority to supervise, and in 1881 education among the Mennonites became subject to the Department of Education. The board barely remained in existence until it took over, in conjunction with the church, the supervision of the German language instruction and on its own initiative was able to revive its fruitful work. The district of Chortitza, both in its own settlement and in its daughter settlements, laid great stress on education and spared no expense to make a standard education possible. Chortitza had 40 teachers with 1,500 pupils; the total including the Mennonite subsidiaries of the Chortitza settlement in the province of Ekaterinoslav numbered about 150 teachers with nearly 5,000 pupils (1918). School matters were always a community concern, independent of church denominational relationships.

In matters of administration Chortitza had its county headquarters (Gebietsamt or district administration) in the village of Chortitza with a mayor (Oberschulze) and secretary (Gebietsschreiber). This administration was originally responsible to the Russian supervisory office (Fürsorgeamt) in Odessa and later to the local Russian authorities. The Agricultural Association played an important role in Chortitza but never gained the influence it had under Cornies in the Molotschna. Health and hospital care developed rapidly at the turn of the last century when a hospital was erected and physicians employed. (See M. Hottmann, "Dr. Th. Hottmann," Mennonitisches Jahrbuch, 1953.) -- Cornelius Bergmann

Under Communism

With the outbreak of the Revolution in 1917 the agricultural and industrial development of the Chortitza settlement came to a standstill. From 1917 to 1922 the Chortitza settlement was the battleground of various armies, including the Reds, the Whites, and the Makhnov bands, and was plagued by starvation and epidemics. In 1919 alone, 245 persons were murdered. Through the New Economic Policy (NEP) temporary economic improvement was brought about. The population of the Mennonite villages of the Chortitza settlement increased from 11,666 in 1918 to 13,965 in 1941.

For the first few years of this period the Mennonites were able to maintain their schools, organize their agricultural associations, and continue their religious services. With the erection of the Dneprostroy Dam and the nationalization and enlargement of the Mennonite factories and milling industries, a tremendous influx of non-Mennonite population came into the Chortitza settlement. In addition to 2,178 Mennonites, the village of Chortitza had nearly 12,000 Ukrainians, Russians, and persons of other nationalities in 1941. As a result many mixed marriages took place.

Many Chortitza Mennonites, especially among the cultural leaders, left Russia in 1922-27 and went to Canada. The year 1927-28 marked the end of the NEP, the time of relative freedom, the possibility of immigrating to America; it was followed by five-year plans and speeded-up collectivization, industrialization, and the exile of ministers and kulaks to Siberia and the Far North. From 1929 to 1941 a total of 1,456 Mennonites were exiled from the Chortitza settlement (before the outbreak of the war). The size of the family decreased rapidly. The average number of children per family had originally been 6.2. When in 1929 Mennonites from all parts of Russia came to Moscow to secure passports in order to leave the country, the Chortitza Mennonites were strongly represented.

A new reduction of the population occurred after the outbreak of the war with Germany in 1941. It was the intention of the Soviet government to evacuate the total civilian population eastward, particularly the element of German background. In the settlements east of the Dnieper River they succeeded quite well. Because of the German Blitz war they were not so successful in the settlements west of the river. Yet they evacuated 831 from the Chortitza settlement. When the German army finally occupied the Ukraine, 2,287 of the 13,965 Mennonites of the Chortitza had been exiled or evacuated. Forty-three per cent of the families had been deprived of the breadwinner.

The End

During the German occupation of the Ukraine (1941-43) the Mennonite farmers gradually returned to private farming, and the educational system of former years was revived. The Chortitza Zentralschule even commemorated its centennial in 1942. However, this revival of cultural traditions was only of short duration. In the fall of 1943 Germany began to evacuate the Mennonite settlements of the Ukraine. From 28 September to 20 October the inhabitants were taken to Germany in trains consisting of some fifty freight cars, each carrying approximately 1,200 persons. Most of them reached their destination within ten days. They were to be settled in West Prussia and the Warthegau (formerly the province of Posen in western Poland).

When in January 1945 the Red army entered Germany most of the newly settled Mennonites fled westward, scattering all over the country. Not all were able to escape from the Russian zone and even those that found themselves in the Western zones were sometimes turned over to the Russian officers for repatriation. It is estimated that a total of 35,000 Mennonites from Russia had been evacuated to Germany, of whom about two thirds were forcibly repatriated by the Russians. Of those 35,000, approximately 11,678 were from the Chortitza settlement. If two thirds of them were also returned to Russia it would leave about 4,000 who have found new homes in Canada and South America. Those that were returned to Russia were sent beyond the Ural Mountains. Individuals may have returned to their former homes but the Chortitza Mennonite settlement exists no more, except in the minds and hearts of those who once called it their home.

Bibliography

Bondar, C. E. Sekta Mennonitov v Rossii. Petrograd, 1916.

Ehrt, A. Das Mennonitentum in Russland . . . . Berlin, 1932.

Epp, D. H. Die Chortitzer Mennoniten. Odessa, 1889.

Fast, Gerhard. "The Mennonites under Stalin and Hitler." Mennonite Life (April 1947): 18 ff.

Friesen, Peter M. Die Alt-Evangelische Mennonitische Brüderschaft in Russland (1789-1910) im Rahmen der mennonitischen Gesamtgeschichte. Halbstadt: Verlagsgesellschaft "Raduga", 1911.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. I, 348-351.

Hildebrandt, P. Erste Auswanderung der Mennoniten aus dem Danager Gebiet nach Südrussland. Halbstadt, 1888.

Klaus, A. Unsere Kolonien. Odessa, 1887.

Kuhn, W. "Cultural Achievements of the Chortitza Mennonites." Mennonite Life (July 1948): 35-38.

Neufeld, Dietrich. Tagebuch aus dem Reiche des Totentanzes. Emden, 1921.

Quiring, H. "Die Auswanderung der Mennoniten aus Preussen 1788-1870." Auslanddeutsche Volksforschung. Stuttgart, 1938: v. II, 1, 66-71.

Quiring, J. Die Mundart von Chortitza in Süd-Russland. Munich, 1928.

Rempel, David. G. "The Mennonite Colonies in New Russia . . ." Unpublished doctoral dissertation at Stanford University, 1933.

Stumpp, Karl. Bericht über das Gebiet Chortitza . . . . Berlin, 1943.

| Author(s) | Cornelius Bergmann |

|---|---|

| Cornelius Krahn | |

| Date Published | 1955 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Bergmann, Cornelius and Cornelius Krahn. "Chortitza Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1955. Web. 22 Nov 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Chortitza_Mennonite_Settlement_(Zaporizhia_Oblast,_Ukraine)&oldid=134980.

APA style

Bergmann, Cornelius and Cornelius Krahn. (1955). Chortitza Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 22 November 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Chortitza_Mennonite_Settlement_(Zaporizhia_Oblast,_Ukraine)&oldid=134980.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, pp. 569-574. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.