Difference between revisions of "Schleitheim Confession"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

SamSteiner (talk | contribs) |

SamSteiner (talk | contribs) (→Bibliography: typo correction) |

||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

Stayer, James M. ''Anabaptists and the Sword'', 2nd ed. Lawrence, Kan.: Coronado Press, 1976. | Stayer, James M. ''Anabaptists and the Sword'', 2nd ed. Lawrence, Kan.: Coronado Press, 1976. | ||

| − | _____. "Swiss-South German Anabaptism, 1526-1540," in ''A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700'', ed. John D. Roth | + | _____. "Swiss-South German Anabaptism, 1526-1540," in ''A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700'', ed. John D. Roth and James M. Stayer. Leiden: Brill, 2007: 83-117. |

Strübind, Andrea. ''Eifriger als Zwingli. Die frühe Täuferbewegung in der Schweiz''. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 2003. | Strübind, Andrea. ''Eifriger als Zwingli. Die frühe Täuferbewegung in der Schweiz''. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 2003. | ||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

_____. "Der Kristallisationspunkt des Täufertums." ''Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter'' (1972): 35-47. | _____. "Der Kristallisationspunkt des Täufertums." ''Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter'' (1972): 35-47. | ||

| − | _____. ''Christian Attitudes to War, Peace, and Revolution''. Elkhart, 1983. | + | _____. ''Christian Attitudes to War, Peace, and Revolution''. Elkhart, 1983. |

= Original Mennonite Encyclopedia Articles = | = Original Mennonite Encyclopedia Articles = | ||

Latest revision as of 18:50, 19 August 2022

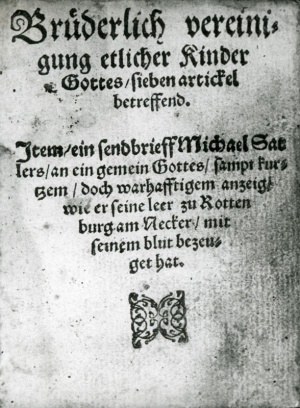

Scan courtesy of Mennonite Church USA Archives-Goshen X-31.1, Box 18/3

The Seven Articles of Schleitheim, composed by a group of Anabaptist leaders in Schaffhausen on 24 February 1527, are a "theological landmark" of early Anabaptism, in the words of John Howard Yoder, the most prominent American Mennonite theologian of the 20th century. An Anabaptist group led by Michael Sattler, and almost certainly including Wilhelm Reublin, laid down a series of Ordnungen concerning baptism, the ban, the Lord's Supper, separation, congregational leadership, the Sword of temporal power, and the oath, distinguishing themselves "from some false brothers among us" whom they excluded. A strong current in 20th-century Mennonite scholarship assessed the Schleitheim Articles as "the crystallization point of Anabaptism," to use Yoder's description. He wrote: "The Anabaptists who first introduced believers' baptism, who formed organized congregations, who persevered despite persecution…distinguished themselves as a unified group with firm contours…Müntzer, Hubmaier, Denck and the Appenzellers disappeared from Anabaptism before 1530, while the Anabaptists who stood upon the foundations of Zurich and Schleitheim…lived on from decade to decade."

This position took the Schleitheim Articles as the historic standard of "true Anabaptism," and either minimized or denied the importance of the several Anabaptist/Mennonite groupings, Yoder maintained throughout his life. In a qualified sense, Yoder's stress on the significance of the Schleitheim Articles has been continued by American Mennonites such as John D. Roth and Gerald Mast, who have studied their historic impact. For Roth, they served as a very important "point of reference" in "framing a set of questions that continued to preoccupy the Swiss Brethren" to the time of the Amish Division at the end of the 17th century, and continue to echo up to the present among Mennonites in the Swiss-South German tradition. However, the American Mennonite scholars who have learned from Yoder have modified and softened some of his contentions. Yoder seemed to deny all group differences among the Anabaptist/Mennonites, except the obvious one with the communal Hutterites. His successors no longer do so, nor do they understand the study of Hubmaier's following, the Austerlitz Brethren, the Anabaptists in Münster, the Jorists, etc. as a diversion from or distortion of the history of the Anabaptist/Mennonite heritage. They have absorbed the better understanding and less polemical appraisal of these groups in recent scholarship. Nevertheless, beyond accepting that the Schleitheim Articles raised issues discussed by early Anabaptists in Switzerland, south Germany and Moravia, it is a matter of some importance to know to what extent the positions set forth at Schleitheim were accepted. And then there is a subtly different question: how authoritative and well-known were the Schleitheim Articles themselves in early Anabaptism.

Arnold Snyder suggests that in "A Summary of the Entire Christian Life," published 1 July 1525, Balthasar Hubmaier established the ecclesiological foundations of Anabaptism – the baptism of adult believers, the ban, and the Lord's Supper. Accordingly, with the addition of four articles on separation, congregational leadership, the Sword of temporal power, and the oath, the Schleitheim Articles, rather than being the "crystallization point of Anabaptism," marked a portentous Anabaptist division between the separatists and the non-separatists.

Article 4 "on separation" was crucial: "Truly all creatures are in but two classes, good and bad, believing and unbelieving, darkness and light, the world and those who have come out of the world, God's temple and idols, Christ and Belial; and none can have part with the other." Examples of worldly wickedness were "all papalist and anti-papalist works and church services, meetings and church attendance, drinking houses, civic affairs, and oaths sworn in unbelief….There will unquestionably fall from us the unchristian, devilish weapons of force – such as sword, armor and the like, and all their use either for friends or against one's enemies…."

Article 5 was "on pastors in the congregation of God." It marked an Anabaptist turning away from the traditional benefice system, participated in by Balthasar Hubmaier both at Waldshut and in Nikolsburg. "This office shall be to read, to admonish and teach, to warn, to discipline, to ban in the congregation, to lead all sisters and brothers in prayer and the breaking of bread…The pastor shall be supported by the congregation that has chosen him, to the extent that he is in need…Should it happen that this pastor is banished or brought home to the Lord through martyrdom, another shall be ordained in his place in the same hour…"

Article 6 is an agreement about "the sword": "The sword is ordained of God outside the perfection of Christ. It punishes and puts to death the wicked, and guards and protects the good. In the Law the sword was ordained for the punishment of the wicked and for their death; it is now conferred upon the worldly magistrates. In the perfection of Christ, however, only the ban is used as a warning and for the excommunication of the one who has sinned, without putting the flesh to death…." Christ's refusal to mediate between brothers in a dispute over inheritance, and his flight when he was he was to be made king are presented as models for Christian behaviour. The article concludes "it is not appropriate for a Christian to serve as a magistrate because of these points: The government magistracy is according to the flesh, but the Christian's is according to the Spirit; their houses and dwelling remain in this world, but the Christian's are in heaven; their citizenship is in this world, but the Christian's citizenship is in heaven."

The last article, Article 7, "on the oath" repeats the allusions to the model and instructions of Christ of the preceding article: "Christ, who teaches the perfection of the Law, prohibits all swearing to his people, whether true or false – neither by heaven nor by the earth, nor by Jerusalem, nor by our head – and that for the reason that he gives shortly thereafter, For you are not able to make one hair black or white…Christ also taught us along the same line when he said, Let your communication be Yea, yea; Nay, nay; for whatsoever is more than these cometh of evil…."

There is disagreement among scholars about the original intention of the authors of the last four articles of the Schleitheim Seven. Specifically, it is questioned whether Article Four "on separation" and Article Six "on the sword" are entirely in harmony with each other. Particularly since harmony of Article Four and Article Six would seem contrary to the normal interpretation of Romans 13, cited in the text, scholars such as John Yoder and Hans Hillerbrand have insisted that Article 6 means that temporal governments and the Christian congregation are two parallel, legitimate manifestations of God's will for his human creation. Arnold Snyder, who has made a special study of Michael Sattler, insists that Article 6 was meant to be entirely consistent with Article 4. Sattler's use of good-evil, Christ-Satan dualisms in his other writings confirms that his intention was to say that temporal government was inherently antagonistic to the congregation of Christ. Andrea Strübind and James Stayer, who disagree on much else, are of the same opinion as Snyder about Sattler's intention.

Throughout the 16th century the substance of the latter four articles of the Schleitheim Seven remained the "default position" or the "sectarian distinctives" of the two major southern Anabaptist groups, the Swiss Brethren and the Hutterites. They underlay the expressions of the Swiss Brethren spokesmen in the religious disputations between them and the established Protestant churches, as well as Peter Riedemann's Rechenschaft (1540-41), the authoritative statement of Hutterite belief and practice. However, they were not accepted by many of the most prominent leaders of the southern Anabaptists. Whenever an Anabaptist leader (or future Anabaptist leader) had been connected with the German Peasants' War of 1524-26, he either opposed or substantially modified the teachings of Schleitheim Articles 4 through 7. This applied to Balthasar Hubmaier, Hans Hut, Hans Denck, Hans Rӧmer, and Melchior Rinck. These persons had been associated with what was perhaps the most important religious mass movement of the early German Reformation; hence, a rigid separatism of the sort enunciated in Schleitheim Article 4 did not correspond to their experiences and beliefs.

A few months following the Schleitheim Articles, in June 1527, Balthasar Hubmaier published On the Sword in Nikolsburg (Mikulov), Moravia, where he was serving a German-speaking Anabaptist congregation. This tract was clearly a repudiation of the substance of Schleitheim Article 6, a viewpoint brought to Moravia by Anabaptists fleeing persecution in Switzerland and south Germany. Later that same year Hans Hut, the major Anabaptist missionary in south Germany and Austria, imprisoned in Augsburg, explicitly rejected the two most distinctive Schleitheim Articles, 6 and 7, on the sword and the oath. The Anabaptist congregation in Augsburg was the scene of confrontation between Anabaptist refugees from Switzerland, most prominently Jakob Groβ, and Hut, who had been an associate of Thomas Müntzer in 1524 and 1525.

Hans Denck, the spiritualist Anabaptist who baptized Hut on Easter 1526, and who was probably schoolmaster in Mühlhausen in Thuringia before its fall in the course of the Peasants' War in May 1525, is a more ambiguous case. In On the True Love, published in Worms in 1527, he undertook a nuanced exegesis of Scheitheim, Articles 6 and 7, in which he extracted much of their separatist bite. On Article 6 Denck took the position that temporal government and the Christian congregation are parallel expressions of God's will, although the Christian congregation was the higher one. Nevertheless, "whoever loves the Lord, loves him in whatever estate he finds himself." On the oath, Article 7's strictures were repeated. Nevertheless, Denck continued, a distinction should be made between swearing to do something in the future (which was beyond human power) and testifying to what had occurred in the past; and one might call on God as a witness for one's statement, as the New Testament showed Paul to do. Hans Rӧmer, a follower of Thomas Müntzer, was at the center of an Anabaptist conspiracy to seize Erfurt on New Year's Day 1528. Melchior Rinck, the Hessian Anabaptist leader, had been one of Müntzer's captains at Frankenhausen. In a pamphlet he addressed to temporal rulers, he appeared unacquainted with Schleitheim, Article 6. He called on the temporal government to extend religious liberty, naming those who provided such freedom "Christian princes," while those who denied it were "heathen rulers."

Another factor that accounted for the form Anabaptism took in the 1520s and 1530s was the policy on toleration or suppression of Anabaptists taken by governmental authorities that had recently adopted the Reformation. John Oyer's study of the Imperial city of Esslingen showed that under circumstances where the government did not try to eradicate Anabaptism, but contented itself with exacting a degree of conformity, the insistence of Schleitheim Article 5 on formal congregational leadership could be abandoned by Anabaptists. The Esslingen Anabaptists always insisted that they had no particular leaders or teachers but assembled simply for the purpose of reading the Bible. A similar state of affairs seems to have prevailed in the Swiss region of Appenzell, and in Strasbourg in the years preceding the formal organization of the Strasbourg Reformation in 1533. This helps us to understand the presence of various currents of Anabaptism in Esslingen, Appenzell, and Strasbourg without formal internal Anabaptist schisms.

Formal Anabaptist schisms (as opposed to the division implied by the Schleitheim Articles) seemed to have first occurred in Moravia, beginning with the expulsion in 1528 from the Liechtenstein territories of Anabaptists who insisted on a stricter form of community of goods. These communitarian Anabaptists settled in Austerlitz, but further schisms divided them in 1531 and 1533. By the 1540s Moravian Anabaptists wrote of differences between Austerlitz Brethren, Swiss Brethren, and Hutterites. The most prominent spokesman of the Austerlitz Brethren became the Tyrolean refugee Pilgram Marpeck, an engineer who worked at various times for the governments of Strasbourg, Appenzell, and Augsburg. Marpeck, like his fellow Austerlitz Brethren, took oaths of citizenship when his circumstances required, hence did not strictly conform to Schleitheim Article 7. The Austerlitz Brethren present a case of the waning influence of the Schleitheim Articles. In the original 1528 schism, they represented the ideas of the Schleitheim Articles against Hubmaier and his supporters. If, as is now generally accepted, Marpeck was the author of the Aufdeckung der Babylonischen Hurn (ca. 1531), he and his close associate, Leupold Scharnschlager, at first echoed the strict prohibition of Christian participation in government of Schleitheim Article 6, no doubt with borrowings from Martin Luther's Von weltlicher Obrigkeit (1523). The point of transition seems to have been the major persecution of 1535, in which the original leaders of the Austerlitzers lost their lives, and after which the group abandoned community of goods. In the 1540s and 1550s Marpeck and his associates carried on an extensive doctrinal controversy with the Spiritualist Caspar von Schwenckfeld, in which he rejected Schweckfeld's attempt to connect his beliefs with Schleitheim Article 6. In the Verantwortung, which came to be a more or less canonical statement of the later beliefs of the Austerlitz Brethren, the position on the sword was that "it is difficult for a Christian to be a temporal ruler." An attenuated version of the original Schleitheim dualism questioned "how long [such a person's] conscience would allow him to be a ruler, if he did not want to forsake his God, the Lord Jesus Christ, Christian patience and Christian knighthood – or at least receive damage to his soul and his Christianity…." John Yoder's interpretation of nonresistance according to Schleitheim, Article 6, is broad enough to encompass such a statement of nonresistance as Marpeck's; but Arnold Snyder's study of Sattler insists that Sattler's dualism was sharper than that of the Austerlitzers.

The next phase of Anabaptism was that begun by Melchior Hoffman in Emden in 1530, which was the starting point of the various types of Anabaptism which emerged in the Netherlands, North Sea and Baltic regions. These groups, which included the Anabaptist domination of Münster in Westphalia (1534-35) and its militant successors, the Davidjorites, and eventually the Mennonite/Doopsgezinden traditions, were in their formative stages entirely untouched by the distinctive ideas of the Schleitheim Articles as well as the document itself. It was not until 1560, a year before Menno's death, that the Seven Articles of Schleitheim were first published in Dutch, together with Michael Sattler's letter to the congregation of Horb, and an account of his trial and martyrdom. Arnold Snyder is certainly correct to judge that Sattler's martyr testimony lent authority to the Schleitheim Articles, rather than the Schleitheim Articles giving significance to Sattler's martyrdom.

The question of how widely the text of the Schleitheim Articles circulated in early Anabaptism is a different one from the importance of the distinctive ideas and practices of the Schleitheim Articles in early Anabaptism. In the latter sense, the impact of the Schleitheim Articles on early Anabaptism was immense; but far from universal. The Schleitheim Articles had very little influence on persons who had experienced Anabaptism and the Peasants' War together in 1525 and 1526; they had much less influence in Protestant territories where the governments did not make a serious effort to eradicate Anabaptism; and they did not touch the Anabaptism of the Netherlands, North Sea and Baltic regions until after 1560. On the other hand, they described the practice of most Swiss Brethren and Hutterites, as well as the Austerlitz Brethren, prior to 1535.

However, the circulation of the Seven Articles was, to say the least, much less extensive in early 16th-century Anabaptism than has been implied in the Anabaptist/Mennonite scholarship of the 20th century. Certainly, in the years following 1527, the Seven Articles were widely circulated in the Bern and Basel region of Switzerland and in neighboring southwestern Germany – Ulrich Zwingli commented on this in his Elenchus (1529). Moreover, just as the early Swiss congregational ordinance that circulated together with the Seven Articles reappeared soon afterward in Moravia, probably at Austerlitz, the same can safely be assumed for the Seven Articles. We also know of a printed version of the Articles that was produced between 1527 and 1529 in Worms by Peter Schӧffer the younger. This print also included Michael Sattler's letter to the Anabaptist congregation at Horb and an account of his martyrdom. Two other German versions of the same texts appeared subsequently in the 16th century; and they were translated into Dutch in 1560. Arnold Snyder has noted that subsequent Dutch publications like the Martyrs' Mirror contained the Horb letter and the story of Sattler's martyrdom, but not the Seven Articles. He suggests, very plausibly, that the Sattler martyr story accounted for such circulation of the Schleitheim text as occurred beyond the years immediately following its emergence. There are seven extant 16th- and 17th-century Hutterite manuscript copies of the Seven Articles, which date from the assembling of a Hutterite archive by the presiding elder Peter Walpot (1565-1578). During this time, the Hutterites printed Peter Riedemann's Rechenschaft, which was theologically consistent with the Seven Articles; so we can assume that the Schleitheim doctrine was authoritative in the Hutterite brotherhood. In respect to the 17th century, there is one known Swiss Brethren publication of the Seven Articles of Schleitheim, bound together with the Dordrecht Confession of 1632. Thereafter the Seven Articles disappear from Anabaptist/Mennonite devotional literature, but the Dordrecht Confession continues, as does the Martyrs' Mirror, both in Dutch and after 1780 in German translation.

Unlike the Seven Articles, the Dordrecht Confession in its 18 articles, contains a full statement of Christian doctrines (with a slight nod to the heterodox Christology of Melchior Hoffman) as well as the distinctive Anabaptist practices of baptizing mature believers, foot washing, the ban and shunning of the banned, marriage only with fellow Anabaptists, non-swearing of oaths, and two articles of which the first affirms the role of governments which extend Anabaptists religious liberty, while the second rejects "revenge and resistance to enemies with the sword." The Dordrecht Confession was originally written as a basis for union between Flemish and Frisian Mennonites, previously divided by schism. It seems highly likely, however, that the articles on the oath, the government and Christian nonresistance migrated into the Dordrecht Confession from similar Swiss Brethren practices originally enunciated at Schleitheim. Certainly, the two articles on government and nonresistance moderated the separatism of Michael Sattler. However, the issue of separation from the world was construed differently by the Dutch Mennonites, the Palatinate Mennonites, the Amish, and the American Mennonites who adopted the Dordrecht Confession. The Amish maintained a stance of separation that echoed Schleitheim Article 4, while the Dutch adopted a much milder attitude towards the comfortable world of the Dutch Republic to which they adapted themselves with great success. This ambiguity was read back from Dordrecht to Schleitheim, on the whole incorrectly. Although Waterlanders and Mennonites in Switzerland never adopted Dordrecht, Dordrecht came much closer than Schleitheim to being the Anabaptist/Mennonite consensus that mid-20th century Mennonite scholars imagined for Schleitheim.

Additional Information

This article is based on the original English article that was written for the Mennonitisches Lexikon (MennLex) and has been made available to GAMEO with permission. The German version of this article is available at [1].

Sources

Quellen zur Geschichte der Täufer, vol. 6: Hans Denck Schriften, 2: Religiöse Schriften, ed. Walter Fellmann. Gütersloh 1956.

Quellen zur Geschichte der Täufer in der Schweiz, vol. 2: Ostschweiz, ed. Heinold Fast. Zurich 1973, 26-36.

Quellen und Forschungen zur Geschichte der oberdeutchen Taufgesinnten im 16. Jahrhundert. Pilgram Marpecks Antwort auf Kaspar Schwenckfelds Beurteilung des Buches der Bundesbezeugung von 1542, ed. Johann Loserth. Vienna and Leipzig 1929.

Classics of the Radical Reformation, vol. 1: The Legacy of Michael Sattler, ed. John Howard Yoder. Scottdale 1973, 27-54.

Classics of the Radical Reformation, vol. 13; Anabaptist Texts in Translation, vol. 4: Later Writings of the Swiss Anabaptists, 1529-1592, ed. C. Arnold Snyder. Kitchener 2017.

Bibliography

Goertz, Hans-Jürgen. "Zwischen Zweitracht und Eintracht: Zur Zweideutigkeit täuferischer und mennonitischer Bekenntnisse," Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter (1986/87): 16-46.

Klaassen, Walter and William Klassen. Marpeck. A Life of Dissent and Conformity. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 2008.

Mast, Gerald. Separation and the Sword in Anabaptist Persuasion. Radical Confessional Rhetoric from Schleitheim to Dordrecht. Telford, Pa.: Cascadia, 2006.

Neumann, Gerhard A., "A Newly Discovered Manuscript of Melchior Rinck," Mennonite Quarterly Review (1961): 211-217.

Oyer, John S. "They Harry the Good People Out of the Land." Essays on the Persecution, Survival and Flourishing of Anabaptists and Mennonites. Goshen, Ind.: Mennonite Historical Society, 2000.

Packull, Werner O. Hutterite Beginnings. Communitarian Experiments during the Reformation. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995.

Pries, Edmund, "Oath Refusal in Zurich from 1525 to 1527. The Erratic Emergence of Anabaptist Practice," in Anabaptism Revisited, ed. Walter Klaassen. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 1992: 85-97.

Rothkegel, Martin, "Anabaptism in Moravia and Silesia," in A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700, ed. John D. Roth and James M. Stayer. Leiden: Brill, 2007: 163-215.

Snyder, C. Arnold, "The Birth and Evolution of Swiss Anabaptism (1520-1530)." Mennonite Quarterly Review (2006): 501-645.

_____. "The Influence of the Schleitheim Articles on the Anabaptist Movement: An Historical Evaluation." Mennonite Quarterly Review (1989): 323-344.

_____. The Life and Thought of Michael Sattler. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 1984.

_____. "The (Not-So) ‘Simple Confession’ of the Later Swiss Brethren, Part I: Manuscripts and Marpeckites in an Age of Print." Mennonite Quarterly Review (1999): 677-722.

_____. "Swiss Anabaptism: The Beginnings, 1523-1525," in A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700, ed. John D. Roth and James M. Stayer. Leiden: Brill, 2007: 45-81.

Stayer, James M. Anabaptists and the Sword, 2nd ed. Lawrence, Kan.: Coronado Press, 1976.

_____. "Swiss-South German Anabaptism, 1526-1540," in A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700, ed. John D. Roth and James M. Stayer. Leiden: Brill, 2007: 83-117.

Strübind, Andrea. Eifriger als Zwingli. Die frühe Täuferbewegung in der Schweiz. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 2003.

Yoder, John Howard. Die Gespräche zwischen Täufer und Reformatoren, 1523-1538. Karlsruhe: Mennonit. Geschichtsverein e.V., 1962.

_____. "Der Kristallisationspunkt des Täufertums." Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter (1972): 35-47.

_____. Christian Attitudes to War, Peace, and Revolution. Elkhart, 1983.

Original Mennonite Encyclopedia Articles

1990 Update

By C. Arnold Snyder. Copied by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 5, p. 797-798. All rights reserved.

The Schleitheim Confession (also known as the Brüderliche Vereinigung or the Schleitheim Brotherly Union) has come to be recognized as a watershed articulation of certain Swiss Anabaptist distinctives. Michael Sattler is now accepted as being the primary author of the seven articles. These were ratified on 24 February 1527 during an assembly of Anabaptists in the northern Swiss village of Schleitheim.

The significance of the Brotherly Union was evident immediately: The articles were copied and circulated quickly and extensively in the Swiss and South German Anabaptist communities. Reaction within those communities was not exclusively positive. Some of the articles were contested within Anabaptist circles (e.g., article 6 by Balthasar Hubmaier); Ulrich Zwingli and John Calvin wrote refutations of the confession as a whole.

While Schleitheim's immediate influence on the Anabaptism of the Swiss and South German areas is undeniable, the historical connections linking Schleitheim to the later confessional tradition have yet to be clarified. Schleitheim's teaching on the sword and the oath (articles 6 and 7) became increasingly normative in the Mennonite and Hutterite traditions, but the articles themselves seem not to have been preserved in a confessional sense: there is no obvious direct line of descent from Schleitheim to the later Mennonite confessions such as Dordrecht. The Schleitheim Confession has received significant denominational attention again only following its recovery in the modern period, with particular attention paid to Schleitheim's teaching on the sword.

Some scholarly difference of opinion exists concerning Schleitheim's historical status as a confessional delineator: was it directed primarily against the Protestant reformers, and that only after Bucer and Capito rejected the ecumenical overtures of Michael Sattler? Or was Schleitheim a further development of prior sectarian impulses, and directed primarily to the Anabaptist community? Some historians have noted further that although Schleitheim explicitly rejects social rebellion, it also preserves important demands first enunciated in the Peasants' War of 1525. -- C. Arnold Snyder

1954 Article

By John C. Wenger. Copied by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, p. 447-448. All rights reserved.

The first known Swiss Brethren or Anabaptist confession of faith was entitled Brüderlich Vereinigung etzlicher Kinder Gottes sieben Artikel betreffend ...("Brotherly Union of a Number of Children of God Concerning Seven Articles"). It was drawn up at Schlatten (dialect for Schleitheim), canton of Schaffhausen, Switzerland, on St. Matthias Day, 24 February 1527. The author was almost certainly Michael Sattler; this is evident from the reference to "our assembly, and . . . that which was resolved on therein" in a pastoral letter of Sattler, as well as from a reference in a letter from 50 Swiss Brethren elders to Menno Simons which mentions a brother in whose house the "verdragh (agreement) of Michael Sattler" had been made.

The confession treats of seven topics: baptism, excommunication, the Lord's Supper, separation from the world, shepherds, nonresistance, and the oath. Each of these subjects is discussed briefly and clearly, and is based on the Word of God. Baptism is made a symbol of Christian faith and of one's intention to live a life united with Christ in His death and resurrection. Those who twice refuse private admonition shall on the third occasion be excommunicated from the brotherhood because of their life of sin. Only those can be admitted to the Lord's table who have been united beforehand by Christian baptism and by a common separation from sin. The child of God is called upon by Christ to withdraw from every institution and person which is not truly Christian. Only one church officer is mentioned, the Hirt (shepherd, pastor) whose duties were to read, admonish, teach, warn, discipline, excommunicate, to lead in prayer, to administer the Lord's Supper, and to undertake the general oversight of the congregation. The child of God is to follow absolutely the law of love as taught by the New Testament, and leave the worldly sword to the officers of the state as ordained by God. Oaths are held to be inconsistent for finite creatures, and forbidden for the Christian by the express commands of Scripture. The Schleitheim confession does not give a complete summary of Christian faith, but treats only of the unique emphases of the evangelical Anabaptists of that era or perhaps of the points which were particularly challenged, either by the opponents or by erring brethren within.

The following four editions were known in the 1950s: 1533 (reprinted by Walther Köhler in 1908 as Heft 3 of Band 2, Flugschriften aus den ersten Jahren der Reformation together with valuable introduction); a contemporary but undated edition (reprinted by Heinrich Böhmer in Urkunden zur Geschichte des Bauernkrieges und der Wiedertäufer, Bonn, 1910, 2d and 3d ed. in 1921 and 1933) ; a later undated edition of the mid-16th century, unique copy in Mennonite Historical Library at Goshen College; and an edition of 1686 bound with Christliches Glaubensbekantnus. An English translation of the 1533 edition by J. C. Wenger in Mennonite Quarterly Review, 1945, 247-253. Each of the German prints appears together with other items in a single booklet. John Horsch published an English translation in Gospel Herald (1938) and the German text in the Menn. Rundschau (1912). The English text given by W. J. McGlothlin in Baptist Confessions of Faith (Philadelphia, 1911) 3-9 is a translation of the inadequate Latin form of the articles as given by Zwingli in the Elenchus of 1527, which is a translation from a German manuscript copy. Contemporary manuscript copies are in the Heidelberg University Library, Bern Staatsarchiv, and three formerly in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia. Dutch editions appeared in 1560 and 1565 (reprinted by Samuel Cramer in BRN V (1909) 585-613. Beck had published one of the Bratislava copies in his Geschichts-Bücher (1883). Ernst Müller published the Bern copy in his Berner Täufer (1895), and Beatrice Jenny published it (1951) in full in a critical edition. A lost French translation was used by Calvin in his attack against the Anabaptists of 1544 (Brieve Instruction), in which he specifically refutes the confession point by point. -- J. C. Wenger

See also Full text of the Schleitheim Confession

Bibliography of 1990 article

Critical edition of the Brüderliche Vereinigung in Heinold Fast, ed., Quellen zur Geschichte der Täufer in der Schweiz, vol. 2: Ostschweiz (1974): 26-36.

Earliest known Dutch edition Broederlicke vereeninge sommighe kinderen Gods... Item eenen Sendbrief van Michael Sattler. . . . (1560).

Deppermann, Klaus. "Die Strassburger Reformatoren und die Krise des oberdeutschen Täufertums im Jahre 1527." Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter, Jg. 30, n.F. 25 (1973): 24-41.

Goertz, Hans J. Die Täufer: Geschichte und Deutung. Munich: C.H. Beck, 1980: 20-23.

Gospel Herald (Feb. 22, 1977), sp. issue.

Haas, Martin. "Der Weg der Taufer in die Absonderung," in Umstrittenes Täufertum, ed. H.J. Goertz. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, 1977: 50-78.

Harder, Leland. "Zwingli's Reaction to the Schleitheim Confession of Faith of the Anabaptists." Sixteenth Century Journal 11 (1980): 51-66.

Hostetler, Beulah Stauffer. American Mennonites and Protestant Movements. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1987.

Hubmaier, Balthasar. "Von dem Schwert," in G. Westin, Torsten Bergsten, eds., Balthasar Hubmaier Schriften. Gütersloh: Gerd Mohn, 1962: 434-57.

Jenny, Beatrice. Das Schleitheimer Täuferbekenntnis 1527. Thayngen, 1951.

Loewen, Howard John. One Lord, One Church, One Hope, One God: Mennonite Confessions of Faith, Text-Reader Series 2. Elkhart: Institute of Mennonite Studies.

Meihuizen, H. W., J.A. Oosterbaan and H.B. Kossen. Broederlijke Vereniging. Amsterdam: Doopsgezinde Historische Kring, 1974.

Meihuizen, H. W. "Who were the 'False Brethren' mentioned in the Schleitheim Articles?" Mennonite Quarterly Review 41 (1967), 200-222.

Miller, John W. Miller. "Schleitheim Pacifism and Modernity." Conrad Grebel Review 3 (1985): 155-63.

Quiring, Hans. "Das Schleitheimer Täuferbekenntnis von 1527." Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter, Jg. 15, n.F. 9 (1957): 34-40.

Snyder, C. Arnold Snyder. The Life and Thought of Michael Sattler. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1984.

Snyder, C. Arnold. "The Schleitheim Articles in Light of the Revolution of the Common Man: Continuation or Departure?" Sixteenth Century Journal 16 (1985): 419-430.

Stauffer, Richard. "Zwingli et Calvin, Critiques de la Confession de Schleitheim," in The Origins and Characteristics of Anabaptism, ed. Marc Lienhard. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1977: 126-47.

Stayer, James M. Anabaptists and the Sword. Lawrence, Ks.: Coronado Press, 1972, 1976.

Stricker, Hans. "Michael Sattler als Verfasser der Schleitheimer Artikel." Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter, Jg. 21, n.F. 16 (1964): 15-18.

Wenger, J. C. "The Schleitheim Confession of Faith." Mennonite Quarterly Review 19 (October 1945) 243-253, and the literature cited there, particularly Robert Friedmann, "The Schleitheim Confession (1527) and Other Doctrinal Writings of the Swiss Brethren in a Hitherto Unknown Edition." Mennonite Quarterly Review 16 (Jan. 1942): 82-98, and Fritz Blanke, "Beobachtungen zum ältesten Täuferbekenntnis."Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte 37I (1940): 240-249.

Yoder, John H. "'Anabaptists and the Sword' Revisited: Systematic Historiography and Undogmatic Nonresistants." Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschicte 85 (1974): 126-139.

Yoder, John H. Yoder. "Der Kristallisationspunkt des Täufertums." Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter, Jg. 29, n.F. 24 (1972): 35-47.

Yoder, John H., ed. and trans. The Legacy of Michael Sattler, Classics of the Radical Reformation, vol. 1. Scottdale, 1973: 27-43.

Link to English Text of Schleitheim Confession

Text of the Schleitheim Confession

| Author(s) | James M Stayer |

|---|---|

| Date Published | August 2022 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Stayer, James M. "Schleitheim Confession." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. August 2022. Web. 2 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Schleitheim_Confession&oldid=174144.

APA style

Stayer, James M. (August 2022). Schleitheim Confession. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 2 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Schleitheim_Confession&oldid=174144.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.