Conservative Mennonites (Dutch-Prussian-Russian)

The Anabaptist reform movements of the 16th century exhibited in the subsequent centuries an amazing capacity to divide and reunite. This article will survey the dividing and the reuniting of one stream of the Mennonite family, namely, the Dutch Mennonites who migrated to Poland (Prussia), Russia, Canada, and Latin America.

The parallel term "Old Orders" is used principally to refer to North American Swiss-High German-Pennsylvania Mennonites and Amish. It refers to the dividing processes among Amish and Mennonites in which some groups separated in order to conserve or maintain the old ways or the old order (Ordnung). Although the term "Old Orders" was not normally used in the stream of Mennonitism being discussed in this article, the process is present. It is this process which will be described here, under the label "conserving" or "conservative Mennonites."

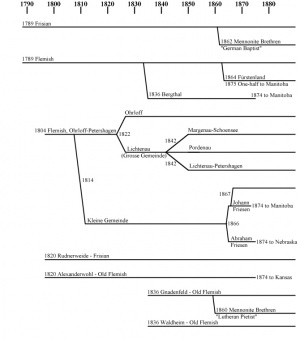

Early Dutch Anabaptists and Mennonites both united and divided. During the time of Menno Simons, the Dutch united into two groups, the Menists or Mennonites, and the Waterlanders. The principal issue dividing these two groups was church discipline. Waterlanders were more lenient and the Menists stricter in exercising church discipline. How church discipline was administered affected their expression of pacifism (nonresistance), relationships to the surrounding culture, intermarriage with non-Mennonites, lifestyle, etc. In 1567, shortly after these two groups had formed, the Menists divided into the Frisian and Flemish factions. Again, the main issue was church discipline, with the Frisians more lenient and the Flemish somewhat stricter. Not long after the division, both groups began to divide into factions, again shaped largely by the stance on church discipline. The Old Flemish attempted to retain the stricter views of the past, whereas the "Soft" Flemish moved closer to the less strict Frisians. The Old Frisians, in trying to retain the old ways, moved closer to the Flemish, and the New Frisians moved closer to the more lenient Waterlanders and High Germans. The people who were the strictest separated from the Old Flemish and formed the Borstentasters, Bankroetiers, and Jan-Lucasvolk factions. Under the influence of the Socinians and the Remonstrants, the focus of issues in the Netherlands shifted from church discipline to doctrine. In 1664 practically all the Dutch groups realigned into two groups, one (the Zonists) which emphasized the necessity of correct doctrine, and another (the Lamists) which emphasized inner personal faith and downplayed the necessity of correct doctrine. These two groupings remained separate until the Napoleonic era, when the central issue shifted to the necessity to educate leaders. Because of serious membership losses by both groups, neither was able to finance the operation of a seminary. Therefore, in 1811 the two groups joined to form the Algemeene Doopsgezinde Sociëteit and jointly provided the finances for the Amsterdam Mennonite Theological Seminary in Amsterdam. The Dutch church had no subsequent divisions.

The Frisian-Flemish division was imported into Poland by 1569, and this division remained in effect when the churches came under Prussian rule in 1772, and even after the immigration to New Russia in 1788. The same issue, church discipline, was the issue which separated the two. As in the Netherlands, the Frisians were more lenient and the Flemish stricter in the use of church discipline. These two groups remained opposed to each other until after the Napoleonic wars when, due to the influence of Pietism and Prussian nationalism, the antagonism gradually disappeared.

When the Chortitza and Molotschna settlements were established in New Russia, the Frisian and Flemish division was still strong enough to result in the formation of separate churches. However, in both settlements, fraternal relationships developed almost immediately so that this division did not have a major impact upon Mennonite life in Russia. In New Russia the central issue which caused divisions was the role that civil Mennonite organizations should play within Mennonite communities. This problem arose because the Russian government insisted that Mennonites, like all other foreign colonists, establish local civil organizations which were to be responsible to the Department of the Interior. The local Mennonite civil organizations were responsible for roads, bridges, and other municipal affairs, as well as local administration of justice. During the days of Johann Cornies, the civil organizations took control of education from church leaders.

Out of this context, two key issues emerged, namely: who was responsible for administering church discipline; and who controlled education the church or civil organizations. The conservers of the "old order" believed that the church should administer church discipline with the traditional patterns of admonition, ban, and reacceptance upon confession. They also believed that the church should control the education of children, and that education should prepare them for membership in the church and local village community. The progressives, or innovators, were willing to see the civil administation take over control of the schools, so that in their view the quality of the schools could be upgraded, and the curriculum could be broadened to include studies far beyond what was necessary for life in a Mennonite village and church. In brief, the innovators were willing to allow the civil administrations to play an increasingly important role in shaping the character of Russian Mennonitism.

In the Chortitza settlement many of the conservers were able to separate themselves from the innovators by moving to the new settlements of Bergthal, founded in 1836, and Fürstenland, founded from 1864 to 1870 (Bergthal Mennonites). In the 1860s the Frisian church in the Chortitza settlement divided, with the formation of a Mennonite Brethren Church under German Baptist influence. The Mennonite Brethren asserted church control over discipline and argued that the old church (Kirchen Gemeinden), from which they were separating, was lax, since, they asserted, everyone was considered a member in good standing, and no test of authentic faith, no discipline was exercised.

The Molotschna settlement suffered more separations than the Chortitza settlement over the issues of how to relate to the civil Mennonite organizations. The first church in the Molotschna colony (founded 1804) was Flemish. Its leaders accommodated to the establishment of civil Mennonite organizations. In 1812 some Mennonites under the leadership of Klaas Reimer objected to this situation in which the civil authorities were taking over the discipline of Mennonite people through the exercise of civil punishments. They argued that the church should exercise discipline through a process which would lead to forgiveness. When the leaders continued to support the civil organizations, the Kleine Gemeinde was formed.

Most members of the Molotschna Flemish Church, even though they did not join the Kleine Gemeinde, nevertheless disagreed with the stance of the leadership, which was accommodating to the civil organizations. Consequently, in 1822 the majority of the Flemish left to form the Lichtenau-Petershagen church. The smaller group which remained with the accommodating leadership was the Ohrloff Church. This group became the center for most innovations in the Molotschna school settlement. It established the first secondary schools, with their new curriculum, and introduced new farming methods. Through Johann Cornies it attempted to impose its innovations upon the rest of the Russian Mennonites.

The Lichtenau-Petershagen Church, also known as the Grosse (large) church, seriously attempted to retain the old ways of administering discipline through the church. They ran into direct conflict with the Russian government, which supported the civil Mennonite organizations. The result was that in 1842 the Russian government broke up the Lichtenau-Petershagen Church into three smaller factions which could be controlled more easily, and forced the elder (Ältester) to abdicate his position.

Four additional churches were formed in the Molotschna settlement as a result of immigration from Prussia. One, the Rudnerweider (1820), was Frisian, and the other three were Flemish, namely Alexanderwohl (1820), Gnadenfeld (1836), and Waldheim (1836). These four accommodated themselves to the prevailing pattern in which the civil organizations had control of discipline and education.

The Mennonite Brethren Church originated in 1860 in the Molotschna settlement. The movement began largely in the context of the Gnadenfeld Flemish congregation, a congregation which had immigrated in 1836. The Mennonite Brethren movement soon drew adherents from throughout the Molotschna settlement. The Mennonites who formed the Mennonite Brethren movement especially criticized the Mennonite churches for being unwilling to exercise the necessary discipline. The problems that the Mennonite Brethren pointed out were largely caused by the influence of the civil Mennonite organizations, which had on the one hand caused the church to relax discipline, and on the other had created a civil Mennonite community in which the churches were not free to exclude anyone from the church. The Mennonite Brethren leaders were thus, in a sense, also conservers, calling the church back to express the discipline of its former days. This critique of the Mennonite churches was, however, not shaped solely by the attempt to restore the old ways. Mennonite Brethren leaders also wanted to implement new ideas learned from Lutheran Pietists or from German Baptists.

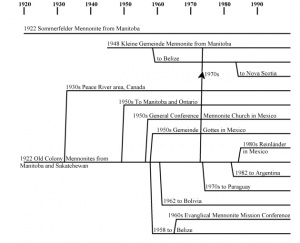

Mennonites who migrated to Manitoba, Canada, in the 1870s came primarily from two sources. One group consisted of one-half of the Kleine Gemeinde (the other half of the Kleine Gemeinde settled in Nebraska). The other group consisted of people from the Bergthal and Fürstenland settlements in Russia which, when they were first formed, had drawn conservers from Chortitza. The Bergthal and Fürstenland people were joined in their trek to Manitoba by conservers from their mother colony, Chortitza. They all hoped to establish settlements in Canada in which the church would have control over education and discipline, and in which civil authority would be subordinate to religious authority. In Canada, however, the situation was quite different from that in Russia. The Mennonite civil organizations, e.g., the village Vorsteher (mayor's office) and regional Obervorsteher, were not supported by the government. These organizations were purely voluntary. Instead of supporting the Mennonite civil organizations, governments proceeded to impose their own civil organizations upon Mennonite settlements. Governments first took over municipal matters and then gradually the education system. Mennonite churches in Manitoba and Saskatchewan found the spheres of community life over which they had authority gradually shrinking. It thus became clear that the policy of the provincial governments was to integrate Mennonites into the Canadian way of life. In Canada, acculturation thus became the issue around which divisions occurred.

Acculturation involved not only questions of authority over schools and community organizations, it involved also faith and beliefs. Those who accommodated usually felt that their earlier theology was inadequate to express their new outlook. In Manitoba two patterns developed for formulating new theologies. Within what became known as the (Manitoba) Bergthal Mennonites, a new theology was shaped through higher education with the establishment of a secondary school at Gretna in 1889. More than three-quarters of the Bergthal-Fürstenland-Chortitza immigrants rejected this option, chose to retain the old ways, and formed in 1893 what became the Sommerfeld Mennonites.

The other pattern the acculturating group used was to shape a new theology on the basis of a revivalist movement. The revivalist movements were rooted in North America and seemed to give better theological expression to a North American way of life. As a result of revivalist influence, half of the Kleine Gemeinde followed its elder into the Church of God in Christ, Mennonite. The other half of the Kleine Gemeinde followed the older ways, eventually becoming the Evangelical Mennonite Conference. In 1888 a small group of Reinländer Mennonites (Old Colonists) left to form the first Mennonite Brethren Church in Canada. The large Reinländer Church continued to follow the old ways (Old Colony Mennonites). In 1898 some Kleine Gemeinde members formed the first Bruderthaler Mennonite Church in Canada. The Kleine Gemeinde followed the old ways.

The conservers feared that by accommodating to the new ways they would jeopardize their faith in God, which included community and peace witness. By the 1920s many of the conservers felt that they could no longer follow the old ways adequately in Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Many conservers immigrated to Mexico and Paraguay, while other conservers, for various reasons, remained in Canada. By the 1930s the Canadian conserving groups consisted of Chortitzer (Conference), Sommerfelder, Old Colony, and Kleine Gemeinde (Evangelical Mennonite Conference) in Manitoba; and Sommerfelder, Bergthaler, and Old Colony in Saskatchewan.

The dividing over the issues of acculturation, accommodation, and revivalism continued. In 1936 a group of more accommodating Sommerfelder Mennonites split to form the Rudnerweider Mennonites (later becoming the Evangelical Mennonite Mission Conference). In 1948, because of the new acculturating pressures caused by World War II, a number of groups of conservers moved to Latin America some Bergthaler, Sommerfelder, and Chortitzer to Paraguay; some Kleine Gemeinde to Mexico. In the 1960s some conservers immigrated to Bolivia.

In 1959 a group of Sommerfelder Mennonites felt that their church had become too accommodating, and left to form the Reinländer Mennoniten Gemeinde. In 1983 a group of Old Colonists who wanted slightly more accommodation left the Old Colony church in Manitoba to form the Zion Mennonite Church. In 1986 a group of Reinländer felt the church had become too accommodating and left to found a new group, the Friedensfelder Mennoniten Gemeinde.

The churches which moved to Latin America were not immune to divisions. Not all the people who emigrated were of one mind about how to relate to the surrounding cultures. In Latin America, in contrast to Canada, the churches usually had much stronger control over the affairs of the whole Mennonite community. The greater autonomy of the Mennonite settlements gave the Mennonite churches greater authority over settlement life. For Mennonite churches in Latin America, the role of church leadership became the central issue around which church divisions tended to develop.

The settlements in Paraguay generally were able to evolve leadership patterns which were representative of the wishes of the people. Thus in Paraguay none of the original settlements from Canada experienced divisions.

The situation was quite different in Mexico. In Mexico the leaders in the Mennonite settlements tended to become increasingly authoritarian and were perceived by some to exercise their authority arbitrarily. Thus the divisions frequently represented revolts against the authority of the church leaders. The formation of mission churches, decisions by some of the Old Colonists to join the Kleine Gemeinde, and by others to join the Reinländer, tended to represent a revolt or rejection of the authority of the church leaders. These revolts usually involved not only theological changes, but were accompanied by changed lifestyle, different clothing styles, changed modes of transportation, and often by the development of better schools. Divisions also happened in the more conserving direction by those who thought that the authority of the church leaders had been eroded too much and that people had gone their own ways too far. These conservers tended to separate by moving to another location to found a new settlement either in Mexico or in another Latin American country.

Conservers have played an important role in the history of the Mennonite people. They have often intuitively sensed the close interrelationship and interdependence between cultural forms and religious values. They have realized that cultural forms become the carriers and communal symbols for theological values. They have seen that values are not free-floating, but rather are incarnated in cultural forms, and that the values and their cultural incarnations cannot easily be separated without destroying the values themselves.

Conservers have frequently been the pioneers in Mennonite migrations. They had the vision and the motivation to move because they valued their beliefs highly enough to give up financial security for an uncertain future. Consequently, they have frequently been the pioneers in new regions in Russia, Canada, and Latin America. Often after they struggled through the pioneer years to build more comfortable settings, their more progressive fellow Mennonites joined them and built on the foundation they had established. Then the progressives frequently, in a mood of ungratefulness, either reviled the conservers for being too conservative, or tried to convert them because they seemed to the progressives to be lacking in spiritual, expressive faith.

From the point of view of the progressives, the conservers have frequently seemed too strongly inward-looking, too closed, and lacking a vision to relate to the larger society. From the conservers' own perspective, they have attempted to emphasize the pre-eminence of faith for all of life, have tried to maintain the structures of community, have sensed the potentially destructive force of individualism, and have been tenacious in maintaining pacifism. They have played an important role within the larger Mennonite community in continuing to witness to Christian values, beliefs, and practices.

| Author(s) | John J Friesen |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1989 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Friesen, John J. "Conservative Mennonites (Dutch-Prussian-Russian)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1989. Web. 27 Apr 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Conservative_Mennonites_(Dutch-Prussian-Russian)&oldid=141076.

APA style

Friesen, John J. (1989). Conservative Mennonites (Dutch-Prussian-Russian). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 27 April 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Conservative_Mennonites_(Dutch-Prussian-Russian)&oldid=141076.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 5, pp. 193-199. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.