Canada

Introduction

Canada is located in the northern part of North America and extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west. On the south it borders the United States and to the north lies the Arctic Ocean and Alaska. Canada is the second largest country by area in the world, comprising 9,984,670 km2 (3,854,085 sq mi). In 2014 the estimated population was 35,540,419.

Canada is a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary form of government. English and French are the nation's two official languages. It is composed of 10 provinces and three territories. The country is rich in natural resources and has one of the highest standards of living in the world.

Aboriginal societies existed in what is now Canada for thousands of years. Europeans first settled in the area around the year 1000, when Norsemen settled for a brief time in Newfoundland. John Cabot explored the Atlantic coast for England in 1497, and Jacques Cartier explored the Saint Lawrence River for France in 1534. Samuel de Champlain established the first permanent settlements in 1605 and 1608 in what later became New France. The Treaty of Paris of 1763 ceded most of New France to Great Britain, and in that same year, the province of Quebec was established. The Quebec Act of 1774 re-established the French language, the Roman Catholic faith, and French civil law in the province. In 1791 Quebec was divided into French-speaking Lower Canada (later Quebec) and English-speaking Upper Canada (later Ontario).

In the Atlantic region, the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713 gave Nova Scotia to the British; most of Acadia, the remaining French colony, became part of Nova Scotia in 1763. In 1769, St. John's Island (now Prince Edward Island) became a separate colony. New Brunswick was formed out of Nova Scotia in 1784 as a result of the settlement of thousands of United Empire Loyalists from the United States. On the Pacific coast, several British colonies were eventually merged to form the the United Colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia in 1866.

Quebec and Ontario formed the province of Canada in 1840 and in 1867, the Atlantic Provinces of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick joined with them to form the Dominion of Canada. Canada assumed control of Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory to form the Northwest Territories in 1870. The province of Manitoba was created in 1870, British Columbia joined Canada in 1871, and Prince Edward Island joined Canada in 1873. The settlement of Europeans in the Northwest Territories led to the creation of the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan in 1905. in 1949, Newfoundland became the 10th Canadian province. Yukon Territory was created in 1898, while Nunavut became Canada's newest territory in 1999.

According to the 2006 census, the largest self-reported ethnic origin was Canadian (32%), followed by English (21%), French (15.8%), Scottish (15.1%), Irish (13.9%), German (10.2%), Italian (4.6%), Chinese (4.3%), First Nations (4.0%), Ukrainian (3.9%), and Dutch (3.3%). A major factor in the growth of Canada's population in recent years has been immigration, especially from Asia and the Middle East. In 1961, less than 2% of the country's population could be classified as belonging to a visible minority group. In 1996, 11.21% of the population belonged to a visible minority group, and in 2006 this number rose to 16.2%. Between 2001 and 2006, the visible minority population rose by 27.2 percent.

According to the 2001 census, 77.1% of Canadians identified as being Christians; of this, Catholics made up the largest group (43.6% of Canadians). The largest Protestant denomination was the United Church of Canada (9.5%), followed by the Anglicans (6.8%), Baptists (2.4%), Lutherans (2%), and other Christians (4.4%). About 16.5% of Canadians declared no religious affiliation, and the remaining 6.3% were affiliated with non-Christian religions, the largest of which was Islam (2.0%), followed by Judaism (1.1%).

1990 Article

Canada, once known as British North America, has been home to Mennonites since 1786. The first Canadian Mennonites came from Pennsylvania and were followed by an intermittent stream of immigrants which swelled on at least three other occasions into major movements of Mennonites to Canada.

The first group of Mennonites that came to Canada were pushed in part by hostility at home arising from their pacifism during the American Revolution. But they were also pulled by the promises and opportunities of a new western agricultural frontier where minority rights seemed better protected than in revolutionary America.

It is estimated that approximately 2,000 Mennonites came from Pennsylvania to Ontario between 1786 and 1825. A detailed Canadian census in 1841 enumerated 5,379 Mennonites, of whom 3,022 lived in the Niagara District, 933 in the Wellington (Waterloo) district, and 859 in the Home (Markham) district.

A second major migration of Mennonites to Canada occurred in the 1870s, when thousands of Mennonites living in Russia sought new homes on North American prairie frontiers. Both American and Canadian authorities were eager to recruit successful settlers and offered major religious, military, and educational concessions. Canada promised more concessions, but economic prospects seemed better on the American frontier. As a result, approximately 7,000 Russian Mennonites migrated to Manitoba in the 1870s, while about 10,000 went to Kansas and Nebraska.

In Manitoba two large land reserves were set aside for the Mennonites in the 1870s, and two more in what would become Saskatchewan in the 1890s. None of these reserves were ever completely filled by Mennonite settlers, and all were eventually thrown open to non-Mennonites. Many other Mennonites moving west from Manitoba, Ontario, the United States, Germany, and Russia chose to take up individual homesteads rather than to occupy land or establish traditional Mennonite villages in the reserved tracts. Mennonite land ownership in Canada therefore developed a rather diverse character.

The third major influx of Mennonites into Canada came as a direct result of the Russian Revolution and Civil War. Approximately 22,000 Russian Mennonites were able to emigrate to Canada between 1923 and 1929, thanks largely to the active support of Mennonites in Canada. Canadian Mennonites worked closely with the Canadian Pacific Railway, and with Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, who had learned to know the Mennonites while growing up in Waterloo, Ontario. The immigrants of the 1920s made no attempt to achieve a geographical separation from the rest of Canadian society and sought no exclusive land grants or reserves.

World War II set in motion the last major wave of Mennonite immigrants to Canada. These were Mennonite war refugees and displaced persons from eastern Europe, of whom about 7,000 came to Canada in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Few of these displaced persons took up farming in Canada on a permanent basis. Instead, they pursued new economic opportunities, usually in the cities, and played a key role in the urbanization of Canadian Mennonites and in their integration into Canadian economic, social, cultural, and educational life.

Canadian Mennonites are a rather divided and fragmented denomination. Major historical distinctions can be made between those who came from Swiss and south German Anabaptist stock, and those from Dutch and North German backgrounds. Most of the former came to Canada from Pennsylvania in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, while most of the latter came from Russia and eastern Europe after 1870. Theologically, these two main streams of Mennonitism have remained close, and after World War II historical and cultural differences have decreased.

Mennonites initially organized themselves into small, local, and relatively autonomous communities and congregations, but in 1825 the first Ontario Mennonite Conference was established. In western Canada some of the Mennonites who had arrived there from Russia and northern Germany after 1870 organized their own conference, the Conference of Mennonites in Central Canada, in 1903. The Mennonite Brethren, a group that had already organized separately in Russia in 1860, organized their own conference in the United States in 1879, with Canadian congregations included in a "Northern District" of the conference. The Mennonite Church (MC, sometimes also known as the "Old Mennonites"), the Conference of Mennonites in Canada (often referred to as "General Conference Mennonites") and the Mennonite Brethren are the three largest Canadian Mennonite groups. The other, smaller conferences and groups manifest much diversity.

Despite the schisms and differences among various Canadian Mennonite groups, they have all joined together to undertake joint relief, immigration, and economic assistance programs. They do so through the Mennonite Central Committee, which was first organized in North America in 1920 to extend economic assistance to Russian Mennonites then hard pressed by war, revolution and civil disorder. Mennonite Central Committee Canada was organized in 1963. Other joint ventures, such as the Conference of Historic Peace Churches, the Non-Resistant Relief Organization, and the Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization were organized for specific purposes and then disbanded.

While relief and economic assistance to those in need could be undertaken jointly, Canadian Mennonites have not been able to achieve a similar unity in their various foreign and home mission ventures. All major and many of the smaller Mennonite groups have committed considerable effort and resources to missionary activities, which have added many new members. Canadian Mennonites have, however, also suffered high attrition rates as various missionary and revival movements have drawn many persons of Mennonite background into other denominations.

Two unique circumstances have greatly influenced the Canadian Mennonite experience. Canada retained British values, emphasizing loyalty, conservatism, respect for parliamentary institutions, and tolerance of minorities. These were values that Mennonites shared, and many of the confrontations with civil authorities that mark the histories of Mennonites in other countries were muted or did not happen at all in Canada. If the Mennonites sought separation, the authorities, with only sporadic exceptions, did little to coerce them into the mainstream of Canadian life. However, when the Mennonites were ready to take a more active role, there were few major barriers or obstacles.

Canada was also the home of a substantial and politically powerful French Canadian minority. Mennonites and French Canadians rarely agreed on major policy issues, but they did reinforce one another, often inadvertently, on the two important issues of military conscription and public school policies.

The French Canadians were a conquered people, cut off militarily from their former homeland in 1759, and also philosophically and spiritually after the French Revolution (1789). They had little interest in remote imperialist conflicts, and strongly opposed any compulsory military service except that required to defend their own homes. Conscription for military service overseas was therefore a hot political issue in Canada. British parliamentary concerns about minority rights led to a search for acceptable alternatives. French Canadians were willing to serve in home defence units, Mennonites in a variety of restricted and alternative services.

Mennonites and French Canadians also shared a strong commitment to separate or private schools. Both had strong legal claims to such schools, the French Canadians and Ontario Mennonites on the basis of terms included in the British North America Act, and the Mennonites in western Canada on the basis of a federal Order in Council passed in 1873.

After 1890, and particularly during and immediately after World War I, some Canadian reformers hoped to eliminate all separate schools and to make the public schools major instruments of assimilation and Anglo-conformity. Educational legislation governing school curricula, patriotic exercises, teacher qualifications, and compulsory school attendance were passed in most Canadian provinces. This offended both Mennonites and French Canadians. The latter resorted to political measures, but at least 7,000 Saskatchewan and Manitoba Mennonites (Old Colony Mennonites) sold their farms and immigrated to Mexico and Paraguay. In this dispute the Mennonites found that the privileges and concessions they had obtained from the federal government in 1873 were of little value, since education in Canada is under provincial jurisdiction.

Canadian school legislation between 1890 and 1920 severely restricted what could be done in private or separate schools, but it did not abolish them entirely. The Canadian Mennonites who stayed accommodated themselves as best they could to the new state of affairs, accepting what could not be avoided while retaining and strengthening their own educational institutions within the changed Canadian context. In the years since the World War I hysteria, and particularly since World War II, Canadian Mennonites have built their own high schools and several colleges; these institutions have achieved high academic standards which are widely recognized by secular colleges and universities.

Early Canadian Mennonite immigrants sought isolation, religious freedom and economic security. In the early years almost all Canadian Mennonites were rural farmers. They have not, however, escaped the influences and events which have shaped Canadian society. Gradually, but at a rapidly accelerating rate after World War II, they have moved into the cities, where most have adopted a social, economic, and cultural lifestyle that is neither separatist nor distinctive. They have sought to redefine and refocus their distinctive beliefs in a manner which permits much greater accommodation but not complete assimilation into Canadian society. Some distinctive and colorful rural remnants remain, particularly in Ontario, but the Canadian census of 1981 showed that only 23 percent of Canadian Mennonites still lived on farms. Fifty-two percent were listed as living in urban centers with the remaining 25 percent being rural nonfarm people. For most Canadian Mennonites traditional separation, with its special life-encompassing value system, has given way to a more accommodating and integrated role in Canadian society. -- Ted. D. Regehr

2010 Update

Mennonites in Canada Census Figures

| Province | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1941 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | 39 | 45 | 90 | 30 | 10 |

| Prince Edward Island | - | - | 3 | 2 | - | 6 | 1 | 15 | 5 | 20 | 10 |

| Nova Scotia | 9 | 18 | 2 | 1 | 23 | 23 | 31 | 90 | 220 | 560 | 790 |

| New Brunswick | - | 1 | 4 | - | 5 | 30 | 5 | 90 | 180 | 240 | 155 |

| Quebec | 50 | 51 | 6 | 8 | 80 | 220 | 197 | 655 | 1,075 | 1,670 | 425 |

| Ontario | 12,257 | 12,861 | 13,665 | 17,683 | 22,256 | 25,796 | 30,948 | 40,115 | 46,485 | 52,645 | 60,595 |

| Manitoba | 15,289 | 15,709 | 21,321 | 30,375 | 39,395 | 44,667 | 56,823 | 59,555 | 63,490 | 73,450 | 51,540 |

| Saskatchewan | 3,787 | 14,586 | 20,568 | 31,372 | 32,553 | 26,270 | 28,174 | 26,315 | 26,265 | 29,190 | 19,570 |

| Alberta | 546 | 1,555 | 3,131 | 8,301 | 12,119 | 13,528 | 16,269 | 14,645 | 20,540 | 32,305 | 22,785 |

| British Columbia | 11 | 191 | 173 | 1,095 | 5,119 | 15,387 | 19,932 | 26,520 | 30,895 | 39,150 | 35,490 |

| Yukon, Northwest Territories & Nunavut | - | - | 1 | - | 4 | 8 | 33 | 100 | 125 | 190 | 100 |

| Totals | 31,949 | 44,972 | 58,874 | 88,837 | 111,554 | 125,938 | 152,452 | 168,150 | 189,370 | 229,460 | 191,470 |

Source: Census of Canada for each of the above years. In 1871, 1881, and 1891, no separate figures were given for Mennonites. In 1871 and 1881 they were included with Baptists, and in 1891 they were included with other denominations. These figures include Amish, Hutterites, and Brethren in Christ, to the degree that they identified themselves as Mennonite to census workers. Figures include children, i.e., are not limited to baptized church members. In the 2001 census 20,590 Canadians identified themselves as Brethren in Christ, a group related to Mennonites.

Anabaptist Groups In Canada, 2020

| Group | Members 2009 |

Congregations 2009 |

Members 2020 |

Congregations 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beachy Amish Mennonite Fellowship | 235 | 8 | 143 | 2 |

| Be in Christ Church of Canada | 3,490 | 43 | 9,187 | 92 |

| Bergthaler Mennonite Church Inc. | 798 | 5 | 870 | 6 |

| Canadian Conference of Mennonite Brethren Churches | 37,751 | 245 | 34,693 | 237 |

| Christian Mennonite Conference | 1,842 | 15 | 1,119 | 10 |

| Church of God in Christ, Mennonite (Holdeman) | 4,949 | 55 | 5,546 | 59 |

| Conservative Mennonite Church of Ontario | 689 | 11 | 838 | 13 |

| Eastern Pennsylvania Mennonite Church | 223 | 4 | 281 | 7 |

| Evangelical Bergthaler Mennonite Church | 1,076 | 7 | ||

| Evangelical Mennonite Conference (Canada) | 7,232 | 60 | 5,945 | 66 |

| Evangelical Mennonite Mission Conference | 4,205 | 23 | 3,500 | 25 |

| Fellowship of Evangelical Bible Churches | 1,606 | 22 | 24 | |

| Hutterian Brethren Church | 14,040 | 352 | 14,900 | 369 |

| Independent Old Order Mennonites | 800 | 6 | 1,000 | 7 |

| Kleine Gemeinde Mennonite Church | 660 | 12 | ||

| Maranatha Amish Mennonite Churches | 125 | 2 | ||

| Markham-Waterloo Mennonite Conference | 1,450 | 14 | 1,645 | 17 |

| Mennonite Church Canada | 32,000 | 221 | 26,000 | 203 |

| Midwest Mennonite Fellowship | 1,015 | 10 | 2,240 | 13 |

| Nationwide Fellowship Churches | 994 | 23 | 1,225 | 24 |

| New Reinland Mennonite Church of Ontario | 330 | 1 | ||

| Northeastern Mennonite Conference | 24 | 1 | ||

| Old Bergthaler Churches | 150 | 2 | ||

| Old Colony Mennonite Church | 9,336 | 25 | 13,778 | 29 |

| Old Order Amish | 2,100 | 35 | 2,100 | 46 |

| Old Order Mennonites - Ontario | 3,000 | 18 | 4,000 | 36 |

| Orthodox Mennonite Church | 4 | 409 | 5 | |

| Reformed Mennonite Church | 120 | 2 | 100 | 2 |

| Reinland Mennonite Church | 4,093 | 13 | 3,403 | 20 |

| Sommerfeld Mennonite Church | 2,300 | 13 | 2,300 | 13 |

| Unaffiliated Amish Mennonite Congregations | 40 | 1 | 118 | 3 |

| Unaffiliated Mennonite Congregations | 499 | 9 | 392 | 8 |

| Western Conservative Mennonite Fellowship | 59 | 1 | 122 | 2 |

Some numbers are estimates. The Be in Christ total in 2020 is for average attendance.

See also Amish; Bergthal Mennonites; Conservative Mennonite Church of Ontario; Conservative Mennonite Fellowship; Fellowship Churches; Mid-West Mennonite Fellowship; Northern Light Gospel Mission Conference; Old Colony Mennonites; Reformed Mennonites; Reinländer Mennoniten Gemeinden; Zion Mennonite Church; Alberta Provincial Conference of the Mennonite Brethren Church; British Columbia Conference of Mennonite Brethren Churches; Mennonite Church Alberta; Conference of Mennonites in British Columbia; Conference of Mennonites in Canada; Conference of Mennonites in Manitoba; Conference of Mennonites of Saskatchewan; Conference of the United Mennonite Churches of Ontario; Manitoba Conference of Mennonite Brethren Churches; Mennonite Conference of Eastern Canada; Mennonite Conference of Ontario and Quebec; Western Ontario Mennonite Conference; Northwest Mennonite Conference; Ontario Conference of Mennonite Brethren Churches; Quebec Conference of Mennonite Brethren Churches; Alberta; Atlantic Provinces; British Columbia; Manitoba; Ontario; Quebec; Saskatchewan.

Bibliography

Epp, Frank H. Mennonites in Canada, 1786-1920: The History of a Separate People. Toronto: Macmillan, 1974.

Epp, Frank H. Mennonites in Canada, 1920-1940: A People's Struggle for Survival. Toronto: Macmillan, 1982.

Kraybill, Paul N., ed. Mennonite World Handbook. Lombard, Ill.: Mennonite World Conference, 1978: 312-81.

Mennonite World Conference. "Global Map: Canada." Mennonite World Conference. Web. 29 March 2021. https://mwc-cmm.org/global-map.

Mennonite World Conference. "World Directory: Europe." Web. 13 June 2010. [broken link}.

Penner, Peter. No Longer at Arm's Length: A History of Mennonite Brethren Home Missions in Canada. Winnipeg: Kindred Press, 1986. Available in full electronic text at: https://archive.org/stream/NoLongerAtArmsLengthMBChurchPlantingInCanadaOCRopt?ref=ol#mode/2up.

Regehr, T.D. Mennonites in Canada, 1939-1970 : A People Transformed. Toronto: University of Toronto, 1996.

Reimer, Margaret Loewen, ed. One Quilt, Many Pieces. Waterloo, ON: Mennonite Publishing Service, 1983.

Reimer, Margaret Loewen. One Quilt Many Pieces: A Guide to Mennonite Groups in Canada, 4th ed. Waterloo, ON: Herald Press, 2008.

Sider, E. Morris. The Brethren in Christ in Canada: Two Hundred Years of Tradition and Change. Napanee, IN, 1988.

Wikipedia. "Canada." Web. 9 October 2011. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canada.

Original Mennonite Encyclopedia Article

By Cornelius F. Klassen. Copied by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, p. 502. All rights reserved.

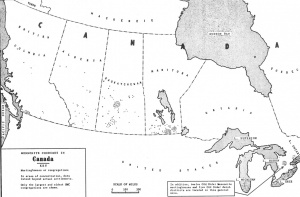

Canada covers the whole of the North American continent north of the United States, excepting Alaska. Her area of 3,847,597 square miles is greater than the whole of Europe. The physical characteristics and the extreme cold of the northern part make that section uninhabitable. More than 90 per cent of the nation's estimated more than 14,000,000 people live in the narrow belt bordering on the United States.

On the Atlantic seaboard are the four Maritime Provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland. The latter was Britain's first colonial possession, taken in 1583. The land is heavily forested with the exception of Prince Edward Island, and the cleared portions form excellent farming districts, except for northern Newfoundland, which is rocky, barren, and bleak. The region's 1,454,410 people gain their livelihood mainly from the products of the farm, the forest, and the sea. There are no Mennonites living in this area.

Next, the Laurentian Shield, as it is commonly known, is an area of low-lying, evergreen-clad hills, forming a huge basin centering on Hudson Bay in the north. The trapper, the miner, and the logger are its only inhabitants. There is a wealth of minerals in this remote territory. Canada leads the world in the production of nickel and asbestos. Gold, silver, copper, lead, and iron are among other minerals found here. The pulp and paper industry has gained tremendous proportions. The centers of population of this region lie just to the south of the Shield, in the valley of the St. Lawrence River and on the shores of the lower Great Lakes. The St. Lawrence Valley is the center of the French Canadian population, and contains Montreal, Canada's largest city, as well as Quebec, the oldest city. In the vicinity of the lower Great Lakes is found the center of the English-speaking community of Canada. These two areas combined contain the largest proportion of Canadian industrial establishments. Mennonites are to be found only in southern Ontario, having established the first Mennonite settlements in Canada here 1786 ff.

West of the Great Lakes lie the prairies, an ocean of wheat waving in the west winds, and stretching from the Red River to the Rockies, the "bread basket" of the world. Approximately one billion bushels of the several grains, wheat, oats, barley, are produced annually. On this land also are raised 10 million cattle, 8 million hogs, and 3.5 million sheep. Almost everywhere mixed farming is the rule. Nearly 2.5 million people live on the prairies. The three prairie provinces are Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. Large numbers of Mennonites are to be found here, the first having come from Russia to Manitoba in 1874.

Between the prairies and the Pacific Ocean lie the mountains. There are several parallel ranges, of which the Rockies are the best known, and the highest and most rugged. In this whole mountainous region there are only a very few valleys that are inhabited. The coast range of mountains everywhere drops abruptly to the sea. Only the few long-lying coastal valleys are habitable. The most important of these is the valley of the lower Fraser River. At the head of this valley is Canada's great Pacific seaport, Vancouver. In the valley, dairying, poultry farming, and berry and fruit growing are the important occupations. Large and growing Mennonite settlements were established here 1928 f1.

Canada's northland is inhabited only by a few trappers, traders, and Eskimos. The airplane has made this arctic north increasingly accessible. There are many mines in the far north whose only contact with civilization is by airplane.

Almost all the people of Canada are of European origin. The two basic stocks are French and British. The British total 5,716,000 and the French Canadians, living largely in the province of Quebec, number upwards of 3,483,000. There are large numbers of Germans, Scandinavians, Ukrainians, Jews, Dutch, Poles, Italians, and others representing almost every nation on the globe. Indians and Eskimos have dwindled to 125,000. Mennonites of all descriptions number about 120,000 souls. The Roman Catholic Church claims about 42 per cent of the population, and enjoys special privileges in the province of Quebec. The Protestants constitute 55 per cent of the population. The Anglican and Presbyterian churches are prominent. The urban dwellers have outnumbered the rural in Canada since 1921. At present, 54 per cent of Canada's population lives in cities and towns. Canada is no longer merely a producer of primary raw materials. Heavy industry today accounts for 45 per cent of gross production, agriculture 20 per cent.

Newfoundland was discovered in 1497 by John Cabot, who was sponsored by a group of Bristol merchants. Jacques Cartier took possession of the land around the Gulf of St. Lawrence for the King of France in 1534. In 1583 Newfoundland was claimed by the English. Britain defeated France in the Seven Years' War and, as a result, Canada came under British control in 1763. In the hundred years following 1763, the colony grew rapidly and kept up a continuous struggle for self-government, which was granted in 1867 when the provinces of Quebec, Ontario, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick entered into a confederation with Dominion status within the British Empire. The Canadian Pacific Railway linked British Columbia to the rest of the Dominion in 1885, and the other provinces joined soon. The Dominion of Canada is a democracy. It is ruled by a Parliament consisting of the King, represented by the Governor-General, the Senate, and the House of Commons. The Senate is appointed and the members of the Commons are elected by the people. The Prime Minister and his ministers are members of the Commons or the Senate. The Cabinet holds office only while it enjoys the confidence of the representatives of the people.

This democratic country has become a home for many Mennonites in their search for a land of religious freedom. The first group came from eastern Pennsylvania to the Niagara peninsula in 1786 to settle in Welland and Lincoln counties of what later became the province of Ontario. In the years immediately following, others came, locating principally in three centers: Waterloo County, the Markham district, and the Niagara district. They were among the pioneers of Canada. The little Mennonite village of Ebytown in Waterloo County, named Berlin in 1827, has become the present large city of Kitchener, the center of the largest compact Mennonite settlement in Canada. Between 1786 and 1825 about 2,000 Mennonites migrated from Pennsylvania to Ontario. The first congregation of Amish Mennonites was organized in Waterloo County in 1824, coming from Bavaria and Alsace-Lorraine.

A second influx of Mennonites began in 1874, this time from the steppes of faraway southern Russia. They settled on the virgin prairie of Manitoba. The government reserved two blocks of land for them, one on each side of the Red River —the East Reserve and West Reserve. They were among the first to attempt to live on the plains away from the rivers. After overcoming severe and prolonged hardships, this group succeeded in making of the two "reserves" one of the most substantial and desirable farming areas in the West. Jacob Y. Shantz, a layman of Waterloo County, played a great role in establishing these settlements.

The third and largest wave of Mennonite immigrants to Canada from Russia began in 1922, and continued through to 1930. This movement brought well over 20,000 Mennonites into Canada, the majority of whom settled on farms in the West. This settlement differed from the previous ones in that it was, in most cases, impossible to obtain large blocks of land, and the settlers had to be interspersed with the rest of the population. Frequently the new settlers went to the cities temporarily where money could be earned more directly and more easily. Some stayed in the cities, and thus the urbanization of the Mennonite population of western Canada began. At present both Kitchener-Waterloo and Winnipeg have five or more Mennonite congregations. Saskatoon and Vancouver are other larger Canadian cities containing relatively large Mennonite populations. The emigration of several thousand Manitoba and Saskatchewan Mennonites to Mexico and Paraguay (1921-1927) during this time should not be forgotten.

The fourth wave of immigration, 1947-1952, from Russia (via Germany) brought another group of more than 7,000, largely to the west. This time over 200 German Mennonites from the former Danzig area joined the migrants.

Internal westward migration movements should be noted. The first of these (1890 ff.) took Manitoba General Conference Mennonites to Saskatchewan, particularly around Rosthern and Herbert. From 1891 to 1903 several small groups of Ontario Mennonites, representing both the Mennonite Brethren in Christ and the Mennonites (MC), settled in Central Alberta, a small group of the latter also in Saskatchewan. The greatest movement of all, however, beginning in 1925 and still continuing, was from the prairie provinces to the Fraser Valley of British Columbia. According to the 1951 census the total Mennonite population of 125,938 was distributed over the Canadian provinces as follows: Manitoba, 44,667; Saskatchewan, 26,270; Ontario, 25,796; British Columbia, 15,387; Alberta, 13,529; Quebec, 220; Nova Scotia, 23; New Brunswick, 30; Prince Edward Island, 6; Newfoundland, 3. The largest city populations (in cities over 5,000) are as follows: Winnipeg, 3,460; Saskatoon, 1,663; Kitchener, 1,646; Vancouver, 1,624; Swift Current, 621; Waterloo, 527; St. Catherines, 510.

The education of their children has been of great concern to the Mennonites of Canada, the first Mennonite school, the Mennonite Collegiate Institute at Gretna, Man., having been established as early as 1891. Here the religious aspect has come first, as the many small Bible schools dotting the Mennonite settlements testify. The Mennonite Brethren, the General Conference Mennonites, the United Missionary Church, and the Mennonites (MC) each have a Bible college. The colleges or Bible institutes of the first two conferences are located in Winnipeg, Man., and the other two in Kitchener, Ont. Every province in which Mennonites reside now has a Mennonite high school: Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia have one each, and Manitoba and Ontario have two each. In these institutions the regular courses are taught, in addition to some religious instruction, some Mennonite history, and the German language. However, the majority of the Mennonite young people attend the public schools.

Organizationally the various Mennonite district or provincial conferences in Canada belong to the general conferences of their bodies, which represent both the United States and Canada, although the relation of the Canadian Conference of the G.C. Mennonite Church is somewhat different from the relationship in the case of the M.B. and the Mennonite (MC) conferences. The first conference organized in Canada was the Ontario Mennonite (MC), organized about 1825. The Canadian Mennonite Conference (GCM) was organized in 1903. The Canadian Mennonites generally support the church-wide boards and institutions of their denominational connections instead of organizing separately for the Canadian constituents. However, several intergroup Canadian Mennonite organizations have developed to serve exclusively Canadian Mennonite interests and needs, such as the Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization, the Non-Resistant Relief Organization (Ontario), the Conference of Historic Peace Churches (Ontario), the Western Canada Mennonite Central Relief Committee. And in Ontario the Brethren in Christ cooperate closely with the Mennonites in relief and peace work. All Canadian Mennonites cooperate with the Mennonite Central Committee, which has a Canadian headquarters in Waterloo, Ont. In a real sense the Canadian Mennonites and the Mennonites of the United States constitute a unified North American group, in which the political boundary between the two nations has little significance. The complete absence of any significant hindrance to a free crossing of the border, as well as the common Anglo-Saxon culture and English language, together with great similarity in political, social, and religious institutions, has made this genuine Mennonite unity possible. There is actually no distinctive Canadian Mennonitism, as contrasted to that of the United States, except that most of the Canadian Mennonites of Russian background still use the German language in their worship services, and have not come as much under the influence of North American Protestantism as their counterpart bodies in the United States.

The relation of the Canadian Mennonites to the state with reference to military service is discussed in detail elsewhere (see Military Participation). Suffice it to say here that the Canadian government has always been generous in dealing with conscientious objectors. There has never been compulsory military training or service in Canada except during wartime. In the war of 1812-1815 between England and the United States, some of the Mennonite settlers of the Waterloo County area were impressed with their horses and wagons to aid in military transport. Mennonites (and Quakers and Tunkers) were always excused from militia duty on payment of a nominal exemption fee. The immigrants from Russia 1874-1880 received special written assurances that they would be free from military service. In World War I Mennonites were exempt from all service although occasional difficulties arose. In World War II alternative civilian service was required (see Alternative Service Camps), and a generally satisfactory solution of the problems related to this question was found.

The Mennonites of Manitoba of the 1874-1880 immigration remained culturally and linguistically (as well as religiously) distinct from their Canadian Anglo-Saxon neighbors, maintaining the German language and even German schools. This cultural autonomy, expressly tolerated by the government at the beginning (the cultural autonomy of the French Canadians made this easy and natural), caused no difficulties until rising Canadian nationalism with its insistence on cultural uniformity brought pressure on the Mennonites for cultural assimilation. This came to a climax in World War I when the situation was complicated by the bitter Canadian anti-German feeling. When the Manitoba government prohibited German schools in 1914, the more conservative Mennonite groups felt their security threatened, and most of them sought and found homes elsewhere (1922-1927) in Mexico and Paraguay (see Old Colony Mennonites).

The conservative Manitoba Mennonites, often called Old Colony, but actually properly called Chortitza or Sommerfeld groups, present a strikingly different phenomenon in North American Mennonite history, similar in some ways, however, to the Old Order Amish and the Hutterian Brethren. Their attempt to maintain complete cultural autonomy on religious grounds failed, in contrast to the successful maintenance of such autonomy by the Mennonites in Russia from whence they came. Not only did they fail in their attempt—they suffered a tragic degree of cultural and religious deterioration, partly because they were too small a group, but partly also because they were completely cut off from all outside sources of cultural renewal. The removal to Mexico and Paraguay has only intensified their isolation and cultural introversion.

The older Mennonite group in Ontario, of Pennsylvania origin, early made a successful transition to Canadianization as an English-speaking, culturally progressive, but sturdily Mennonite body, although a fraction, the Old Order Mennonites, has continued a certain degree of cultural retardation. The large newer immigrant group from Russia (1922-1930), coming with a higher cultural and religious level to begin with, has not followed the pattern of the Old Colony Manitoba group but rather that of the Ontario group, although the first generation has strongly maintained the German language.

The Canadian government for its part has consistently evidenced a high regard for the Mennonites, no doubt largely because of their solid contribution to the national welfare through their community building and their agricultural achievements in both Ontario and the prairie provinces. The late and long-time Prime Minister W. L. Mackenzie King was a native of Waterloo County, Ont., and knew the Mennonites well. His influence was frequently brought to bear on their behalf in times of difficulty with the state and in connection with immigration policies.

Mennonite Membership in Canada by Conference Groups in 1951

| General Conference Mennonites | 15,500

|

| Mennonite Brethren | 9,579

|

| Mennonite Church (MC) | 6,335

|

| Sommerfelder Mennonites | 3,785

|

| United Missionary | 2,866

|

| Old Colony Mennonites | 2,049

|

| Evangelical Mennonites (Kleine Gemeinde) | 1,895

|

| Old Order (Wisler) Mennonites | 1,840

|

| Rudnerweide Mennonites | 1,800

|

| Chortitz Mennonites | 1,408

|

| Church of God in Christ, Mennonite | 1,292

|

| Evangelical Mennonite (former E.M.B.) | 630

|

| Old Order Amish Mennonites | 610

|

| Krimmer Mennonite Brethren | 310

|

| Reformed Mennonites | 221

|

| Total | 40,120

|

Bibliography

In 1953 there was little literature in English on the general history of the Mennonites in Canada. In the German language there was:

Schaefer, P. J. Die Mennoniten in Canada, which is Part 3 of Woher? Wohin? Mennoniten! Altona, MB, 1945.

Lehmann, H. Das Deutschtum in Westkanada. Berlin, 1939.

See also:

Erfahrungen der Mennoniten in Canada während des zweiten Weltkrieges. Steinbach, n.d.

Ewert, B., ed. Wichtige Dokumente betreffs der Wehrfreiheit der Mennoniten in Canada. Gretna, 1917.

Francis, E. K. "The Mennonite School Problem in Manitoba." Mennonite Quarterly Review 27 (1953): 204-236.

Francis, E. K."A Bibliography of the Mennonites in Manitoba." Mennonite Quarterly Review 27 (1953): 237-247.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. II, 456-458.

Smith, C. Henry. The coming of the Russian Mennonites: an episode in the settling of the last frontier, 1874-1884. Berne, IN, 1927.

Yoder, S. C. For Conscience Sake. Goshen, IN, 1940.

| Author(s) | Ted D. Regehr |

|---|---|

| Richard D. Thiessen | |

| Date Published | October 2011 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Regehr, Ted D. and Richard D. Thiessen. "Canada." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. October 2011. Web. 12 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Canada&oldid=179337.

APA style

Regehr, Ted D. and Richard D. Thiessen. (October 2011). Canada. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 12 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Canada&oldid=179337.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 5, pp. 121-124. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.