Difference between revisions of "Ceramics"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

AlfRedekopp (talk | contribs) |

AlfRedekopp (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

Emanuel Suter (1833-1902) married Elizabeth Swope in 1855, and they settled on the Swope family farm three miles west of Harrisonburg. There he built a small kiln, which he apparently operated until 1866. In 1864, he fled northward, a refugee with his family from the Civil War. This brought to a close the early period of his pottery-making, during which he made both earthenware and stoneware. His few known pieces from this period are most highly decorated. Suter was exempt from military service because his potter skills were needed to make tableware. Heatwole had not applied for the exemption. As he fled northward, Suter began a daily account of his experiences. This ongoing practice resulted in a set of diaries reaching to 1902, constituting a unique record of the life of an American potter. | Emanuel Suter (1833-1902) married Elizabeth Swope in 1855, and they settled on the Swope family farm three miles west of Harrisonburg. There he built a small kiln, which he apparently operated until 1866. In 1864, he fled northward, a refugee with his family from the Civil War. This brought to a close the early period of his pottery-making, during which he made both earthenware and stoneware. His few known pieces from this period are most highly decorated. Suter was exempt from military service because his potter skills were needed to make tableware. Heatwole had not applied for the exemption. As he fled northward, Suter began a daily account of his experiences. This ongoing practice resulted in a set of diaries reaching to 1902, constituting a unique record of the life of an American potter. | ||

| − | [[File:Polingaysi%20Qoyawayma.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Polingaysi Qoyawayama, ca. 1970. | + | [[File:Polingaysi%20Qoyawayma.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Polingaysi Qoyawayama, ca. 1970. |

| + | |||

| + | Source: Mennonite Church USA Archives 2013-0142m'']] <tr> <td colspan="2"><span class="style1">''Polingaysi Qoyawayama, ca. 1970. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </span></td> </tr> | ||

While in [[Pennsylvania (USA)|Pennsylvania]], Suter worked for a few months for the large Cowden and Wilcox Pottery Company in Harrisburg. In 1866, back in [[Virginia (USA)|Virginia]], he began building a much larger kiln and pottery shop for his New Erection Pottery. The new shop was two stories high. This new operation was very successful for 25 years. It produced large quantities of utilitarian stoneware and earthenware, generally undecorated. More than 75 different kinds of ware are listed in his account books. The most common were crocks, flower pots and saucers, preserve jars, butter churns, milk pans, and spittoons. In 1890 Suter moved his operation to town near the railroad, where it was known as the Harrisonburg Steam Pottery Company. In preparation for building the new pottery, Suter had spent the summer of 1890 visiting potteries in Pennsylvania and [[Ohio (USA)|Ohio]] to learn the latest methods. The undecorated stoneware produced here was covered with gray or tan slip outside and Albany slip inside. By 1897, internal administrative problems prompted Suter to sell out. The operation failed soon after that. | While in [[Pennsylvania (USA)|Pennsylvania]], Suter worked for a few months for the large Cowden and Wilcox Pottery Company in Harrisburg. In 1866, back in [[Virginia (USA)|Virginia]], he began building a much larger kiln and pottery shop for his New Erection Pottery. The new shop was two stories high. This new operation was very successful for 25 years. It produced large quantities of utilitarian stoneware and earthenware, generally undecorated. More than 75 different kinds of ware are listed in his account books. The most common were crocks, flower pots and saucers, preserve jars, butter churns, milk pans, and spittoons. In 1890 Suter moved his operation to town near the railroad, where it was known as the Harrisonburg Steam Pottery Company. In preparation for building the new pottery, Suter had spent the summer of 1890 visiting potteries in Pennsylvania and [[Ohio (USA)|Ohio]] to learn the latest methods. The undecorated stoneware produced here was covered with gray or tan slip outside and Albany slip inside. By 1897, internal administrative problems prompted Suter to sell out. The operation failed soon after that. | ||

Revision as of 01:06, 14 February 2018

1953 Article

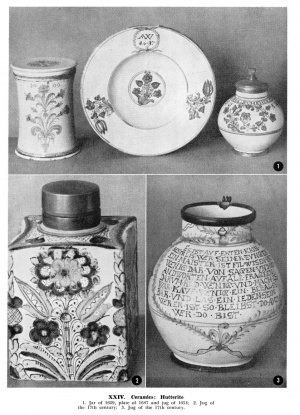

One of the crafts engaged in by the Hutterian Brethren in Moravia which attracted much attention was the art of ceramics or pottery. Their chronicles speak of it merely as the potter's trade (Hafnergewerbe), but the earthenware produced in their shops included more than is commonly understood by this term. There were all kinds of articles for domestic use, such as plates, bowls, vases, and pitchers, many of them having artistic value.

The importance of these products was not recognized until the 20th century. Items were found in several museums, but their source was unknown, and, though it has been definitely established that they were Hutterite products, they were incorrectly listed in the literature describing them. They were usually called Habaner faience; but they were produced before the Thirty Years' War, and the name Habaner is used only to designate those Hutterites in Hungary who under government pressure turned Catholic in the 18th century. The Habaner were still engaged in pottery, but the china which has aroused the interest of investigators is the Hutterite product of the earlier period. The Hutterite chinaware is worked out with delicate artistry, especially dinnerware, which was much used for gift purposes by the nobility. A letter written on 5 October 1612, stated that Johann Dionys von Zierotin at Seelowitz near Brno sent the wife of the Margrave of Brandenburg, Johann Georg, a large load, drawn by four horses, of "white earthen dishes of all sorts and several pairs of knives, such as the Anabaptists here regularly manufacture."

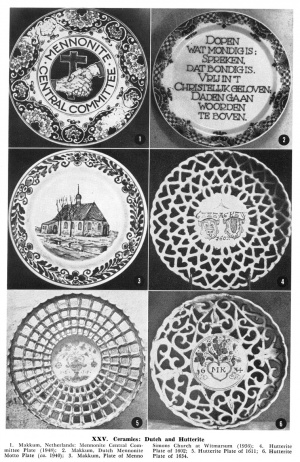

Dutch & Hutterite ceramics. Source: Mennonite Encyclopedia, v. 1, Photograph plates XXIV-XXV In the period preceding the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War it was common usage among the noble families in Moravia to have a large supply of chinaware from the Hutterite colonies. In the castles of Catholic noblemen, who were in many cases friendly toward the Hutterites, their products were used, usually expensive pieces. The inventories still in existence speak for the popularity of Hutterite faience. The inventory of 1615 of a room in the castle of Ladislaus Berka, the adviser of the Prag government under Rudolf II, lists besides valuable silver, also "41 white Anabaptist earthen dishes." The "confiscation commission" appointed in 1621 after the Bohemian revolt found in a series of drawers in the castle of Adam Schampach von Pottenstein in Weissenkirchen "eleven Anabaptist dishes," and in a green painted chest "much Anabaptist china and glass." Some of this confiscated ware was taken to Vienna in 1624 as a gift from Emperor Ferdinand II to Empress Eleonora. There is probably not an inventory of a Moravian castle which does not list some Hutterite faience. Hutterite art objects were also purchased by the Moravian barons for foreign noblemen. The correspondence of Johann Dionys (of the Zierotin family) shows that in 1611 he bought for the Margrave of Brandenburg a richly gilded carriage of their workmanship; in 1609 iron bedsteads were ordered for the Austrian nobleman, Wolf Sigmund von Losenstein, and in 1613 through the latter for the imperial vice chancellor. Hutterite knives and earthenware were delivered to friends in Silesia. An inventory of 26 May 1618, in the archives of the castle of Falkenberg in Upper Silesia, listing the estate left by Weighard von Promitz and Polyx, has as item 37, "a blue Anabaptist jug mounted in silver and gilded"; as item 194, "Anabaptist dishes, jugs, pitcher, basins, and bowls"; another lists "25 pairs of Anabaptist knives." Hutterite products were likewise popular in middle-class circles. The description of the home of Anna Zedlarin in Zlin, Moravia, 22 September 1622, lists in one room "not a little Anabaptist china and glass," in another room a cupboard containing "Anabaptist dishes," in a third, "a smaller painted cupboard full of various glass jugs and other Anabaptist dishes." The production of chinaware was very profitable to the Hutterite community. Their shops were the only ones in Moravia. The secret of its china manufacture was strictly guarded in all countries, and was known only to a few. Where the Hutterites learned it is not known. It is not unlikely that some of the refugees from Italy were ceramic craftsmen, as for instance those who escaped from Ferrara, which was at that time a pottery center, and which lies only 45 miles north of Faënza, then the center of majolica manufacture. They built their first faience potteries in Gostal in 1593, near Lundenburg, and in Neudorf near Hradisch. The Hutterite faience differs from the products of other countries in the choice of motif used in decoration. Pictures and figures that might be offensive to religious sensibilities they avoided. By principle they never pictured the human figure. Even animal figures are absent. Plant forms were the favorite motifs. The shapes were also limited by regulation: the Hafnerordnung of 11 December 1612 specified that jugs and cups must not be shaped like books, shoes, etc. When the Hutterites were expelled from Moravia in 1622, they took the secret of china manufacture with them. They used not only special kinds of yellow and white clay, some of which they had to get from distant places, but also definite dyes and mixtures for the ornamentation of the glaze. "They observed a process of their own in the manufacture, with a constantly growing feeling for good form, for lively but harmoniously shaded colors, which we still admire. It was actually impossible to find an equivalent substitute for their work." -- Christian Hege

1987 Article

Research on 19th-century North American Mennonite potters began in the 1970s. Four potters in Canada and two in the United States have been documented by the mid-1980s.

The earliest of these potters was Jacob Bock (1789-1867), who was born in Lancaster County, PA, and came to Waterloo County, Ontario, as a young boy. In 1832 he was elected township clerk, and in 1850 he helped found the Blenheim Mennonite Church, where he served as deacon from 1841 until his death. His 1865 will has been found, and his pottery shop is known to have been located in Waterloo. The three known pieces of his work, each dated 1825, are the earliest dated pieces of Ontario pottery known. They are covered earthenware tobacco jars, each decorated with four relief plaques of St. Ambrose (ca. 240-397).

Cyrus Eby (1844-1906) was a potter in Markham Township, York County, Ontario. He was producing ware in 1862. His grandfather was a Mennonite pioneer from Pennsylvania His father was known as "Potter Sam," and it was from him that he and his brother likely learned the trade. Cyrus's older brother, William K. Eby (1831-1905), was a potter in Conestogo, Waterloo County, ON. The pottery was located just south of Conestogo and east of St. Jacobs. Earlier, in 1855, he had operated a pottery in Markham for two years. He then bought an existing pottery from potter Burton Curtis. Eby was a part-time potter, also supporting himself with farming. An 1890s price list indicates that he produced crocks, pans, jugs, pitchers, flower pots, chamber pots, spittoons, stove tubes, and pie plates "of common earthenware." After 1900, he was assisted by his son, William, Jr. Twin-stemmed cherries are a distinguishing decoration on Eby's pie plates and tableware. His was the last Pennsylvania German pottery in Ontario.

Two potters operating in the United States at about the same time as the Ebys in Canada, were John D. Heatwole (1826-1907) and his cousin, Emanuel Suter (1833-1902). According to family tradition, Suter became an apprentice to Heatwole in 1851. Several pieces survive by each man, dated 1851. Both potteries were located in Rockingham County's Central District, near Harrisonburg, VA. In 1848, Heatwole was married to Elizabeth Coffman. In 1852, they became members of the Bank Mennonite Church, one mile from his pottery.

According to tradition, Heatwole learned the trade from his wife's brother-in-law, Lindsay Morris. Their common father-in-law was Andrew Coffman, another potter of Mennonite ancestry, who was not a member of the church himself. His son and grandson served together in the same regiment in the Civil War. Two signed pieces of Coffman's blue decorated stoneware have survived. His 1853 stoneware tombstone, apparently made by his son, John Coffman, is one of only two examples known. John Heatwole produced the other one.

Heatwole was already listed as a potter in the 1850 census. His pottery was a one-man operation, except for a brief partnership with Joseph Silber in 1866. Silber (d. 1890), a recent immigrant from Baden, Germany, also collaborated with Suter in the same year.

Heatwole 's shop was a small frame building resting on four cornerstones with a dirt floor, near a small two-story log house of four rooms and a mule stable. He produced both lead-glazed earthenware and stoneware. Many of his crocks are highly decorated individual creations; his operation never reached the large commercial proportions of Suter's.

Heatwole's avoidance of military service is legendary. After initially joining the militia in June 1861, he went into hiding after being allowed to return home for fall planting. While in what is now West Virginia, he sowed the seeds of the Mennonite faith there. He was finally able to return to his family in 1865. In the 1880 census he was still listed as a potter.

Emanuel Suter (1833-1902) married Elizabeth Swope in 1855, and they settled on the Swope family farm three miles west of Harrisonburg. There he built a small kiln, which he apparently operated until 1866. In 1864, he fled northward, a refugee with his family from the Civil War. This brought to a close the early period of his pottery-making, during which he made both earthenware and stoneware. His few known pieces from this period are most highly decorated. Suter was exempt from military service because his potter skills were needed to make tableware. Heatwole had not applied for the exemption. As he fled northward, Suter began a daily account of his experiences. This ongoing practice resulted in a set of diaries reaching to 1902, constituting a unique record of the life of an American potter.

Polingaysi Qoyawayama, ca. 1970. While in Pennsylvania, Suter worked for a few months for the large Cowden and Wilcox Pottery Company in Harrisburg. In 1866, back in Virginia, he began building a much larger kiln and pottery shop for his New Erection Pottery. The new shop was two stories high. This new operation was very successful for 25 years. It produced large quantities of utilitarian stoneware and earthenware, generally undecorated. More than 75 different kinds of ware are listed in his account books. The most common were crocks, flower pots and saucers, preserve jars, butter churns, milk pans, and spittoons. In 1890 Suter moved his operation to town near the railroad, where it was known as the Harrisonburg Steam Pottery Company. In preparation for building the new pottery, Suter had spent the summer of 1890 visiting potteries in Pennsylvania and Ohio to learn the latest methods. The undecorated stoneware produced here was covered with gray or tan slip outside and Albany slip inside. By 1897, internal administrative problems prompted Suter to sell out. The operation failed soon after that. Active in the church, Suter was secretary of the Virginia Mennonite Conference (MC) for many years and was influential in promoting Sunday schools. Suter 's 1902 obituary did not mention that he had been a potter. Two potters who came to the craft late in life are to be noted. Born in 1892 in Old Oraibi Hopi village on Third Mesa in Arizona, Polingaysi Qoyawayama, also known as Elizabeth Q. White, completed a distinguished career as a teacher before she retired in 1954 and became a potter. After taking course work at Northern Arizona University, she was known for developing new techniques and working with unusual clays. She produced corn maiden wind bells and decorated pots with raised ears of corn. Her work was highly prized; even broken pieces were saved. John P. Klassen, a Russian Mennonite, was instrumental in leading a group of Mennonite immigrants to Canada in 1923. He had had art training in Munich and Berlin. In 1924, he joined the Bluffton College faculty as a sculptor and painter. In the 1930s and 1940s, he introduced ceramic casting and thrown pottery to the curriculum. Klassen influenced many people to become potters, including American potters Darvin Luginbuhl, Jack Earl, and Paul Soldner. Soldner, of international reputation, is the son of Mennonite pastor G. T. Soldner of Bluffton. Pottery seemed to have special appeal for Mennonites in the 20th century. Ceramic work usually outsells the purely aesthetic media with Mennonite purchasers (painting and printmaking; sculpture); perhaps the functional aspect gives it an edge. But like many Mennonite artists of the past, those of the late 20th century still had to look beyond the church for most of their support. Ceramics classes at Mennonite colleges are popular, and at least 30 Mennonite potters were producing work in the United States alone. These express in their work diverse influences ranging from abstract expressionism to traditional folk art and from one-of-a-kind abstract sculptural forms to functional production ware. -- Stanley A. Kaufman

Bibliography

Specialized literature has given valuable clues in recent years. An interesting pictorial survey of Hutterite faience is given by Karl Layer, the director of the Hungarian museum for crafts in Budapest in Oberungarische Habaner-Fayencen ( Berlin, 1927). Seven other treatises in the Czech language by Karl Cernohorsky of the Silesian museum in Troppau, with the following titles (translated into German):

Beiträge zur Geschichte der mährischen Fayence. Troppau, 1928.

Die Erzeugung der Wischauer Fayence. Wischau, 1928.

Die Anfänge der Habaner-Fayence-Produktion, with 35 photographs illustrating the masterpieces of the Hutterian Brethren 1598-1634. Troppau, 1931; an excerpt in the German language is added, and was reprinted in "Festschrift zum 60. Geburtstage von E. W. Braun." Augsburg, 1932.

Der heutige Stand der Erforschung der sog. Habaner Fayencen. Prague, 1932.

Die Fayenceerzeugung in Wischau. Prag, 1932.

Wiedertäuferische Schale aus dem Jahre 1605 aus den Sammlungen des Städtischen Museums in Böhm. Budweis, 1932.

Die Fayenceerzeugung in Bucowic. Bucovic, 1933.

There is a catalog of an exposition of Hutterite ceramics displayed in Troppau in 1925.

Interesting information from Czech sources is given by Dr. Frantisek Hruby, director of Moravian archives in Brno, in Die Wiedertäufer in Mähren. Leipzig, 1935.

Robert Friedmann published a few pictures of these museum pieces in Mennonite Life (July 1946):, 42 f.

Bird, Michael and Terry Kobayashi. A Splendid Harvest; Germanic Folk and Decorative Arts in Canada. Toronto: Van Nostrand Reinhold Ltd., 1981: 76-79, 157-59, 161.

Good, Reginald. "I. Jacob Bock and his Folk Art." Mennonite Life 35 (December 1980): 20-23.

Kaufman, Stanley A. Heatwole and Suter Pottery. Harrisonburg, VA: Eastern Mennonite College, 1978.

Newlands, David L. Early Ontario Potters: Their Craft and Trade. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson Ltd., 1979: 106-108.

Unrau, Ruth. Encircled: Stories of Mennonite Women Newton, KS: Faith and Life, 1986: 163-75.

| Author(s) | Christian Hege |

|---|---|

| Stanley A. Kaufman | |

| Date Published | 1986 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Hege, Christian and Stanley A. Kaufman. "Ceramics." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1986. Web. 1 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Ceramics&oldid=156794.

APA style

Hege, Christian and Stanley A. Kaufman. (1986). Ceramics. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 1 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Ceramics&oldid=156794.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, pp. 543-544; vol. 5, pp. 131-132. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.