Difference between revisions of "Virginia (USA)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m (Text replace - "</em><em>" to "") |

SusanHuebert (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

The [[Old Order Amish|Old Order Amish]] settlements in the Stuarts Draft ([[Augusta County (Virginia, USA)|Augusta County]]) and Catlett (Fauquier County) areas have disbanded. The Stuarts Draft settlement, begun in 1942, ended in 1981. Those families who did not become a part of the Beachy Amish Mennonites moved to Tennessee. By 1977, the Catlett settlement, which had begun in 1946, had also disappeared. Those who did not join the Beachy fellowship churches migrated to Kentucky. Loss of leadership seems to have been the main reason for the disbanding of these settlements. | The [[Old Order Amish|Old Order Amish]] settlements in the Stuarts Draft ([[Augusta County (Virginia, USA)|Augusta County]]) and Catlett (Fauquier County) areas have disbanded. The Stuarts Draft settlement, begun in 1942, ended in 1981. Those families who did not become a part of the Beachy Amish Mennonites moved to Tennessee. By 1977, the Catlett settlement, which had begun in 1946, had also disappeared. Those who did not join the Beachy fellowship churches migrated to Kentucky. Loss of leadership seems to have been the main reason for the disbanding of these settlements. | ||

| − | With the disappearance of the Old Order Amish from Virginia, the most conservative Mennonites were the Old Order Mennonites of Dayton in Rockingham County Like the Old Order Amish, they prohibited the use of automobiles and commercial electricity, and like them, they experienced external pressures. Scarcity and expensiveness of land made it increasingly difficult for parents to provide children with farms, and farm technology imposed standards which required the use of diesel generators for electricity. Old Order children received no more than an eighth-grade education, and after successfully defending this tradition in court in 1970, the leaders established their own schools. Teachers who lacked a high school education were drawn from within the church. However, consideration was being given to hiring certified teachers. Since the 1950s when a division occurred within the Old Order community, there have been two groups (Wenger and Showalter). They alternated between two of the three meetinghouses for their worship services. The Horning Mennonites in the same area were an offshoot of the Old Order groups. They broke away in 1957 and used automobiles, but they painted the bumpers black. Therefore, they are often called Black Bumper Mennonites. | + | With the disappearance of the Old Order Amish from Virginia, the most conservative Mennonites were the Old Order Mennonites of Dayton in Rockingham County. Like the Old Order Amish, they prohibited the use of automobiles and commercial electricity, and like them, they experienced external pressures. Scarcity and expensiveness of land made it increasingly difficult for parents to provide children with farms, and farm technology imposed standards which required the use of diesel generators for electricity. Old Order children received no more than an eighth-grade education, and after successfully defending this tradition in court in 1970, the leaders established their own schools. Teachers who lacked a high school education were drawn from within the church. However, consideration was being given to hiring certified teachers. Since the 1950s when a division occurred within the Old Order community, there have been two groups (Wenger and Showalter). They alternated between two of the three meetinghouses for their worship services. The Horning Mennonites in the same area were an offshoot of the Old Order groups. They broke away in 1957 and used automobiles, but they painted the bumpers black. Therefore, they are often called Black Bumper Mennonites. |

The seven [[Beachy Amish Mennonite Fellowship|Beachy Amish Mennonite]] Fellowship congregations were found at Catlett (Fauquier County), Stuarts Draft (Augusta County), Madison (Madison County), Farmville (Prince Edward County), and Kempsville in the Norfolk-Chesapeake area. Some were more conservative than others. For example, the Mt. Zion congregation in Stuarts Draft continued the use of the German language in its worship services until 1985, whereas the Faith Christian Fellowship at Catlett was a very outgoing congregation which held revival meetings and whose bishop was director of Choice Books of Northern Virginia, an extensive bookrack evangelism program begun in 1968. Faith Mission Home in Madison, founded in 1965, was a residential home and training center for children who were mentally retarded. In 1983 a lawsuit regarding the use of corporal punishment was filed against the home in an attempt to close it, but the judge granted a temporary stay which was based on appeals to a higher court. No verdict had yet been rendered by the summer of 1986. | The seven [[Beachy Amish Mennonite Fellowship|Beachy Amish Mennonite]] Fellowship congregations were found at Catlett (Fauquier County), Stuarts Draft (Augusta County), Madison (Madison County), Farmville (Prince Edward County), and Kempsville in the Norfolk-Chesapeake area. Some were more conservative than others. For example, the Mt. Zion congregation in Stuarts Draft continued the use of the German language in its worship services until 1985, whereas the Faith Christian Fellowship at Catlett was a very outgoing congregation which held revival meetings and whose bishop was director of Choice Books of Northern Virginia, an extensive bookrack evangelism program begun in 1968. Faith Mission Home in Madison, founded in 1965, was a residential home and training center for children who were mentally retarded. In 1983 a lawsuit regarding the use of corporal punishment was filed against the home in an attempt to close it, but the judge granted a temporary stay which was based on appeals to a higher court. No verdict had yet been rendered by the summer of 1986. | ||

| − | Until 1972, the only major division among Virginia Mennonites took place in 1900 when a group of Old Order Mennonites left the main Virginia Conference body. On 30 June 1972 the second division occurred when a number of congregations again left the Virginia Mennonite Conference to form the [[Southeastern Mennonite Conference|Southeastern Mennonite Conference]]. The main concerns were modern dress and education. Most of the Virginia churches affiliated with the Southeastern Conference were located in Rockingham County One congregation was at Stanardsville (Greene County), and another was located at South Boston (Halifax County). Other churches of the conference were scattered as widely as [[West Virginia (USA)|West Virginia]], [[South Carolina (USA)|South Carolina ]], [[Georgia (USA)|Georgia]], and [[Puerto Rico|Puerto Rico]]. Christian Light Publications, founded in 1969 in Harrisonburg, published the Southeastern Conference periodical <em>Life Lines </em>and other materials used by the conference. One of the pastors owned and operated Park View Press, which printed Southeastern Conference materials and also serves the wider community. The Southeasten Conference had two Christian day schools, one in West Virginia and one near Dayton, Virginia. Two groups, one at Mount Crawford and the other at Timberville, were offshoots of the Southeastern Conference. | + | Until 1972, the only major division among Virginia Mennonites took place in 1900 when a group of Old Order Mennonites left the main Virginia Conference body. On 30 June 1972 the second division occurred when a number of congregations again left the Virginia Mennonite Conference to form the [[Southeastern Mennonite Conference|Southeastern Mennonite Conference]]. The main concerns were modern dress and education. Most of the Virginia churches affiliated with the Southeastern Conference were located in Rockingham County. One congregation was at Stanardsville (Greene County), and another was located at South Boston (Halifax County). Other churches of the conference were scattered as widely as [[West Virginia (USA)|West Virginia]], [[South Carolina (USA)|South Carolina]], [[Georgia (USA)|Georgia]], and [[Puerto Rico|Puerto Rico]]. Christian Light Publications, founded in 1969 in Harrisonburg, published the Southeastern Conference periodical <em>Life Lines </em>and other materials used by the conference. One of the pastors owned and operated Park View Press, which printed Southeastern Conference materials and also serves the wider community. The Southeasten Conference had two Christian day schools, one in West Virginia and one near Dayton, Virginia. Two groups, one at Mount Crawford and the other at Timberville, were offshoots of the Southeastern Conference. |

The Virginia Mennonite Conference experienced much change after the 1950s. Most striking was the shift from agricultural to [[Business|business]] and [[Professions|professional]] [[Occupations|occupations]]. The best example was the [[Warwick River Mennonite Church (Newport News, Virginia, USA)|Warwick River congregation]] in [[Newport News (Virginia, USA)|Newport News]] which in 1987 had only one member who had retained his tract of farmland in what was once a colony of Mennonite farmers. Mennonites in the Newport News-Norfolk area were in the middle of a military-industrial complex. Some were employed in the naval shipyards and other military bases, but most were involved in the thriving building industry of the Tidewater area. Members of the larger congregations in the Shenandoah Valley also consisted mainly of business and professional persons. Change also came about through various types of expansion. New congregations were established in the cities of Roanoke, Christiansburg, Fredericksburg, Waynesboro, and Hampton. Attempts at church planting were made among the Spanish- and Vietnamese-speaking people of the [[Washington (District of Columbia, USA)|Washington, D.C.]], area. A group which had not yet become an established congregation in 1986 was developing in Woodstock. | The Virginia Mennonite Conference experienced much change after the 1950s. Most striking was the shift from agricultural to [[Business|business]] and [[Professions|professional]] [[Occupations|occupations]]. The best example was the [[Warwick River Mennonite Church (Newport News, Virginia, USA)|Warwick River congregation]] in [[Newport News (Virginia, USA)|Newport News]] which in 1987 had only one member who had retained his tract of farmland in what was once a colony of Mennonite farmers. Mennonites in the Newport News-Norfolk area were in the middle of a military-industrial complex. Some were employed in the naval shipyards and other military bases, but most were involved in the thriving building industry of the Tidewater area. Members of the larger congregations in the Shenandoah Valley also consisted mainly of business and professional persons. Change also came about through various types of expansion. New congregations were established in the cities of Roanoke, Christiansburg, Fredericksburg, Waynesboro, and Hampton. Attempts at church planting were made among the Spanish- and Vietnamese-speaking people of the [[Washington (District of Columbia, USA)|Washington, D.C.]], area. A group which had not yet become an established congregation in 1986 was developing in Woodstock. | ||

Revision as of 18:19, 24 February 2016

Introduction

The Commonwealth of Virginia is a state located in the South Atlantic region of the United States of America. Virginia is bordered by Maryland and Washington, D.C. to the north and east; by the Atlantic Ocean to the east; by North Carolina and Tennessee to the south; by Kentucky to the west; and by West Virginia to the north and west. The total area is 42,774.2 square miles (110,785.67 km2) and the estimated population in 2012 was 8,185,866.

The ethnic composition of Virginia was as follows in 2012: Non-Hispanic White 64.0%; Black or African American 19.7%; Hispanic or Latino (of any race) 8.4%; Asian 6.0%; and American Indian and Alaska Native 0.5%. In 2010, Virginians reported the following ancestry: 11.7% German, 10.7% English, 9.8% Irish, 9.7% American, and 1.7% Subsaharan African.

2008 statistics reported the following religious affiliations of Virginians: Christian 76% (Baptist 27%, Roman Catholic 11%, Methodist 8%, Presbyterian 3%, Lutheran 2%, and Other Christian 28%); Buddhism 1%; Hinduism 1%; Judaism 1%; Islam 0.5%; and Unaffiliated 18%.

1959 Article

Virginia, known since the adoption of the first state constitution in 1776 as the Commonwealth of Virginia, is the oldest of the 13 original colonies, founded in 1607. West Virginia was a part of the state until 1863. Geographically present-day Virginia is divided into three areas—the coastal plain or tidewater Virginia, the Piedmont Plateau, and the Great Valley area between the Blue Ridge Mountains on the east and the Alleghenies on the west. Distinction should be made between the Valley of Virginia and the Shenandoah Valley. The latter is only that part of the Valley which is drained by the Shenandoah rivers, tributaries of the Potomac, at Harpers Ferry. The Shenandoah Valley consists of about two thirds of the northern part of the Valley.

Not all the land of colonial Virginia was used for farming; much of it was used for grazing. Here the first roundups and corrals in American history took place. The plantation system did not come to Virginia until after the Revolution, when the price of tobacco was so low that the small farmer was unable to carry on and sold his land to the larger landowner. The result was the plantation system. The exception to the above rule was the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. This area was settled by the Pennsylvania Germans, who proved to be better farmers than the English, preserving and conserving the native fertility of soil. Even in the 1950s Pennsylvania German farms could be recognized.

In many respects local government and church organization in Virginia was a replica of the mother country of England. The county board or bench ruled the county and the vestry board organized on the same pattern was responsible for the religious life of the people. These agencies were self-perpetuating. On the state level, until 1787 Virginia had the state church, the Anglican Church. This meant that everyone in Virginia was expected to join this church. The sumptuary laws of early Virginia were almost as strict as those in Massachusetts. Quakers were banned in 1660; they were not to hold conventicles. In the 18th century dissenters were permitted in the Valley of Virginia. Their coming was the beginning of the breakdown in the state church system. Mennonites, Quakers, Lutherans, and other groups came, followed by the Baptists just before the American Revolution.

These groups in time became champions of religious freedom in the state. The Enlightenment of the 18th century had its influence too. Thomas Jefferson became one of the leaders of the movement. He became a champion for religious freedom and for the disestablishment of the state church in Virginia. Jefferson believed that there should be no compulsion in matters of religion. He was aided in his cause by the dissenters. Some of these, particularly the Baptists, had wholeheartedly participated in the American Revolution. Should they not be free to worship God as they pleased? They naturally thought so and used their participation in the war as a lever to obtain freedom in religion. The Pennsylvania Germans worked with and for Jefferson too. It is said that the Pennsylvania Germans came "down in shoals" to vote for Thomas Jefferson. It was in 1787 that the state church of Virginia was disestablished. Mr. Jefferson considered this as one of three outstanding achievements of his life.

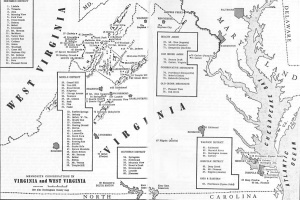

Of the 100 counties in Virginia, Mennonites lived in 15 by the 1950s; viz., Page, Frederick, Shenandoah, Rockingham, and Augusta in the Shenandoah Valley; Fauquier, Orange, Fairfax, Greene, Nelson, and Albemarle, just east of the Blue Ridge; Amelia and Halifax in the center; and Warwick, Norfolk, and Princess Anne on the Atlantic Coast. The most populous Mennonite settlements in the Valley were found in Rockingham and Augusta counties, and in the southeastern part of the state at Denbigh and Fentress in Warwick and Norfolk counties.

The original settlements made in Page, Frederick, and Shenandoah counties in 1728 were nearly wiped out by an Indian raid in 1758. Page County was also the scene of the Rhodes massacre when John Rhodes and members of his family were killed near Luray in 1764. The next two settlements were made in Rockingham County, the first and largest in the Linville Creek, Cedar Run, and Brock's Creek area extending from Edom and Broadway on the east to Turleytown and Cootes Store on the west. In 1773 this area was occupied by the Stovers, Shanks, Brennemans, Brunks, Coffmans, Beerys, and Geils. The above settlement in the northern part of the county soon overflowed to help establish a new and second settlement in the vicinity of Harrisonburg. A third settlement was made soon after the Revolution in Augusta County near Waynesboro.

Most of the Virginia Mennonites who came in 1773-1820 came from Montgomery, Lancaster, and York counties in Pennsylvania. The period 1820-1830 was the time of organization of the oldest existing continuous congregations in Rockingham and Augusta counties. A settlement made in Frederick County (Winchester) in the 1870s died out by 1900-1910. The coastal settlements in Warwick (Denbigh) and Norfolk (Fentress) counties were begun in 1897 and 1900 respectively of different stock, mostly from Allen County, Ohio. The small settlement in Halifax County, near South Boston, was started in 1900. In the first half of the 20th century Old Order Amish settlements were made in the Stuarts Draft (Augusta County) and Catlett (Fauquier County) areas. In both areas Beachy Amish congregations have emerged. Near Kempsville, in Princess Anne County on the coast, an Old Order Amish settlement was established in 1903. In the 1940s the Old Order Amish of Kempsville withdrew to reestablish themselves in the Shenandoah Valley at Stuarts Draft, Augusta County. In the 1950s a Beachy Amish Mennonite church and a Conservative Mennonite church were formed in the Kempsville area. The Conservative Mennonites had two other congregations in the state—one at Gladys, the other at Schuyler, Virginia.

The only division among the Virginia Mennonites occurred about 1900 when a small group of Old Order Mennonites separated from the main Virginia Conference body in Rockingham County. In the 1950s this group had two congregations near Dayton.

Virginia Mennonites by Branches, 1957

| Name | Congregations | Members |

|---|---|---|

| Mennonite Church (MC) | 47 | 3,660 |

| Ohio and Eastern | 1 | 31 |

| Conservative Mennonite | 3 | 115 |

| Virginia Conference | 43 | 3,514 |

| Old Order Amish | 2 | 160 |

| Old Order Mennonite | 2 | 350 |

| Beachy Amish Mennonite | 3 | 259 |

| Total | 54 | 4,429 |

Of this number the 31 congregations of the Virginia Mennonite Conference (MC) in the Shenandoah Valley with their 2,838 members constituted the heart of Virginia Mennonitism, with the Eastern Mennonite College at Harrisonburg as a strong asset. At Harrisonburg also was the headquarters of Mennonite Broadcasts and the Virginia Mennonite Home for the Aged. A second center was the Denbigh-Fentress area around Norfolk, where there were 9 congregations affiliated with the Mennonite General Conference, with 731 members. -- Harry A. Brunk

1990 Update

In 1987 Virginia was the 13th most populous state in the union, numbering 5,787,000, which was 2.4 percent of the total population of the United States. Between 1980 and 1986 Virginia's population increased by 8.2 percent compared with 6.4 percent growth for the nation. Mennonites in Virginia also increased in number. In 1957 there were six groups comprising a total membership of 4,429 in 54 congregations. Thirty years later there were nine conferences and groups, 94 congregations, and 7,332 members. When Brethren in Christ totals are added, the total membership of all Mennonite branches in Virginia and West Virginia was 8,017 distributed among 102 congregations as follows: Virginia Mennonite Conference (MC), 65 congregations, 5,501 members (not including 12 VMC congregations of 392 members in Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Ohio); Atlantic Coast Conference (MC) 1, 38; Southeastern Mennonite Conference, 12, 837; Old Order Mennonites, 3, 584; Beachy Amish Mennonites, 8, 460; Mennonite Christian Brotherhood, 1, 26; Horning Mennonites (Old Order Mennonites, Weaverland Conference), 1, 53; unaffiliated congregations 2, 93; Fellowship Churches, 1, 75; Brethren in Christ, 8, 350.

The Old Order Amish settlements in the Stuarts Draft (Augusta County) and Catlett (Fauquier County) areas have disbanded. The Stuarts Draft settlement, begun in 1942, ended in 1981. Those families who did not become a part of the Beachy Amish Mennonites moved to Tennessee. By 1977, the Catlett settlement, which had begun in 1946, had also disappeared. Those who did not join the Beachy fellowship churches migrated to Kentucky. Loss of leadership seems to have been the main reason for the disbanding of these settlements.

With the disappearance of the Old Order Amish from Virginia, the most conservative Mennonites were the Old Order Mennonites of Dayton in Rockingham County. Like the Old Order Amish, they prohibited the use of automobiles and commercial electricity, and like them, they experienced external pressures. Scarcity and expensiveness of land made it increasingly difficult for parents to provide children with farms, and farm technology imposed standards which required the use of diesel generators for electricity. Old Order children received no more than an eighth-grade education, and after successfully defending this tradition in court in 1970, the leaders established their own schools. Teachers who lacked a high school education were drawn from within the church. However, consideration was being given to hiring certified teachers. Since the 1950s when a division occurred within the Old Order community, there have been two groups (Wenger and Showalter). They alternated between two of the three meetinghouses for their worship services. The Horning Mennonites in the same area were an offshoot of the Old Order groups. They broke away in 1957 and used automobiles, but they painted the bumpers black. Therefore, they are often called Black Bumper Mennonites.

The seven Beachy Amish Mennonite Fellowship congregations were found at Catlett (Fauquier County), Stuarts Draft (Augusta County), Madison (Madison County), Farmville (Prince Edward County), and Kempsville in the Norfolk-Chesapeake area. Some were more conservative than others. For example, the Mt. Zion congregation in Stuarts Draft continued the use of the German language in its worship services until 1985, whereas the Faith Christian Fellowship at Catlett was a very outgoing congregation which held revival meetings and whose bishop was director of Choice Books of Northern Virginia, an extensive bookrack evangelism program begun in 1968. Faith Mission Home in Madison, founded in 1965, was a residential home and training center for children who were mentally retarded. In 1983 a lawsuit regarding the use of corporal punishment was filed against the home in an attempt to close it, but the judge granted a temporary stay which was based on appeals to a higher court. No verdict had yet been rendered by the summer of 1986.

Until 1972, the only major division among Virginia Mennonites took place in 1900 when a group of Old Order Mennonites left the main Virginia Conference body. On 30 June 1972 the second division occurred when a number of congregations again left the Virginia Mennonite Conference to form the Southeastern Mennonite Conference. The main concerns were modern dress and education. Most of the Virginia churches affiliated with the Southeastern Conference were located in Rockingham County. One congregation was at Stanardsville (Greene County), and another was located at South Boston (Halifax County). Other churches of the conference were scattered as widely as West Virginia, South Carolina, Georgia, and Puerto Rico. Christian Light Publications, founded in 1969 in Harrisonburg, published the Southeastern Conference periodical Life Lines and other materials used by the conference. One of the pastors owned and operated Park View Press, which printed Southeastern Conference materials and also serves the wider community. The Southeasten Conference had two Christian day schools, one in West Virginia and one near Dayton, Virginia. Two groups, one at Mount Crawford and the other at Timberville, were offshoots of the Southeastern Conference.

The Virginia Mennonite Conference experienced much change after the 1950s. Most striking was the shift from agricultural to business and professional occupations. The best example was the Warwick River congregation in Newport News which in 1987 had only one member who had retained his tract of farmland in what was once a colony of Mennonite farmers. Mennonites in the Newport News-Norfolk area were in the middle of a military-industrial complex. Some were employed in the naval shipyards and other military bases, but most were involved in the thriving building industry of the Tidewater area. Members of the larger congregations in the Shenandoah Valley also consisted mainly of business and professional persons. Change also came about through various types of expansion. New congregations were established in the cities of Roanoke, Christiansburg, Fredericksburg, Waynesboro, and Hampton. Attempts at church planting were made among the Spanish- and Vietnamese-speaking people of the Washington, D.C., area. A group which had not yet become an established congregation in 1986 was developing in Woodstock.

Institutions too have grown. In 1965 Eastern Mennonite Seminary was established, so that what was once Eastern Mennonite College was now Eastern Mennonite College and Seminary (later Eastern Mennonite University). The college added a science center in 1965, a library and archives in 1971, and a discipleship center in 1974. In 1975 a renovation of the chapel was completed. Four dormitories were added, and when the administration building burned down in 1984, a new campus center was erected two years later in its place. Eastern Mennonite High School (EMHS) became independent from the college and seminary and added cafeteria and industrial arts wings to its structure. Two other church schools were located in Newport News and Chesapeake. Retirement and nursing homes also increased in number and function. What was once the Virginia Mennonite Home for the Aged in Harrisonburg was now a part of the large Virginia Mennonite Retirement Community which included Heritage Haven, Woodland, and Park Village for senior adults, and Oak Lea Health Care Center. In Newport News the Warwick River congregation operated Menno Wood, a retirement home. Pleasant View Homes in Broadway, begun in 1970, had facilities for the handicapped and mentally retarded at that location as well as in Harrisonburg.

In 1958 Highland Retreat, a church camp was begun near Bergton. A retreat center, founded in 1984, was being developed near Williamsburg. A Ten Thousand Villages gift and thrift shop in Harrisonburg and the annual relief sale near Waynesboro help provided funds for Mennonite Central Committee. A voluntary service unit under Mennonite Board of Missions was located in Richmond. Harrisonburg was the headquarters of Mennonite Board of Missions (MC) Media Ministries, formerly known as Mennonite Broadcasts. In 1969 the Park View Federal Credit Union was founded to provide financial services to members of Mennonite organizations in Park View and members of Mennonite churches in Harrisonburg and Rockingham County -- Gerald R. Brunk

| Anabaptist/Mennonite Denominations in Virginia, 2000 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Denomination | Congregations | Adherents |

| Beachy Amish Mennonite Churches | 8 | 681 |

| Brethren In Christ Church | 8 | 429 |

| Church of the Brethren | 175 | 31,421 |

| Conservative Mennonite Conference | 2 | 107 |

| Mennonite Church USA | 59 | 11,517 |

| Mennonite; Other Groups | 23 | 2,978 |

| Old Order Amish Church | 5 | 247 |

| Old Order Mennonite | 6 | 1,030 |

| Total | 286 | 48,410 |

Source: The ARDA: The Association of Religion Data Archives. "Virginia Membership Report, 2000." http://www.thearda.com/mapsReports/reports/state/51_2000.asp (accessed 23 February 2009).

Bibliography

Brunk, Harry A. History of Mennonites in Virginia, 1727-1900. Staunton: McClure Printing Co., 1959.

Brunk, Harry A. History of Mennonites in Virginia, 1900-1960. Verona: McClure Printing Co., Inc., 1972.

Hertzler, Daniel. From Germantown to Steinbach. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1981: 41-53.

Horsch, James E., ed. Mennonite Yearbook and Directory. Scottdale: Mennonite Publishing House (1988-89): 42-43.

Luthy, David. Amish Settlements Across America. Aylmer, ON: Pathway, 1985: 1-2.

Minutes of the 109th [Seventh Biennial] General Conference, Brethren in Christ Church, July 5 - July 10, 1986. Nappanee, Evangel Press, 1986: 20-67, 236-39.

Nardi, Gail. "The Old Order." Richmond Times-Dispatch (9 November 1986): F 1-3.

Nardi, Gail. "The Changing Mennonites." Richmond Times-Dispatch (16 November 1986): F 1, 3, 4.

Wikipedia. "Virginia." Web. 23 December 2013. Web. 28 December 2013. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virginia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virginia.

Yoder, Elmer S. The Beachy Amish Mennonite Fellowship Churches. Hartville, Ohio: Diakonia Ministries, 1987: 253-254, 311-312, 360-367.

Wittlinger, Carlton O. Quest for Piety and Obedience: The Story of the Brethren in Christ. Nappanee, IN: Evangel Press, 1978: 146, 447-48.

| Author(s) | Harry A. Brunk |

|---|---|

| Gerald R. Brunk | |

| Date Published | December 2013 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Brunk, Harry A. and Gerald R. Brunk. "Virginia (USA)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. December 2013. Web. 16 Apr 2025. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Virginia_(USA)&oldid=133679.

APA style

Brunk, Harry A. and Gerald R. Brunk. (December 2013). Virginia (USA). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 16 April 2025, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Virginia_(USA)&oldid=133679.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 4, pp. 829-832; vol. 5, pp. 914-915. All rights reserved.

©1996-2025 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.