Menno Simons (1496-1561)

1957 Article

Scan provided by Mennonite Library and Archives.

MLA Photo 2006-0138

Menno Simons (ca. 1496-1561) was the most outstanding Anabaptist leader of the Low Countries during the 16th century. His followers became known as Mennonites (Mennisten). He was not, however, as is popularly assumed, the founder of the movement in the Netherlands. He became its leader after it had been in existence in that area for a number of years. His significance lies in the fact that he assumed the responsibilities of leadership at the crucial moment of the movement when it was in danger of losing its original identity under the influence of chiliastic and revolutionary leaders who succeeded in winning large followings. He maintained original peaceful Biblical Anabaptist concepts and won many who had been in danger of being swallowed up by the Münsterites.

Menno was born in 1496 (exact date unknown) in the little village of Witmarsum, Dutch province of Friesland. Little is known about his youth and parental home. His parents, who lived in Witmarsum, were very probably dairy farmers. His father's first name was Simon, hence the son's name Menno Simons(zoon). Since Menno did not enter the priesthood until the age of 28, it can be assumed that he made the decision for this career not so early in life. He may have received his training in a monastery of Friesland or in a neighboring province. Menno knew Latin, and Greek was not entirely foreign to him. During his study he acquainted himself with some of the Latin Church Fathers. He did not read the Bible as such before his second year as a priest. Naturally he knew large sections of it, e.g., through the Roman missal.

Albert Hardenberg used Menno Simons as an example of men who had "stupid teachers" and who without "learning and sound judgment ran away from monasteries." He also states that he met Menno as a rural priest. Hardenberg received his training at the Aduard Monastery near Groningen (1527-30) at the time when Menno was serving as a priest in Friesland. What occasion brought the two together? Was Menno also a graduate of Aduard? In that case Hardenberg did not speak very respectfully of his alma mater. In any event not too much significance can be attached to his statement regarding Menno's training since he was jealous of Menno's success and not inclined to give an objective evaluation. He says of Menno that he "took the Bible into his hands without formal training causing such great damage among Frisians, Belgians, the Dutch. . . . Saxons, . . . all of Germany, France, Britain, and all surrounding countries that posterity will not be able to shed sufficient tears because of it" (Spiegel, 117).

In 1524 at the age of 28, Menno was ordained priest at Utrecht. His first parish was Pingjum near Witmarsum, where he served as a vicar, with two colleagues. Judged by his reminiscences he was not deeply convinced of the sacredness of his duties, for he states that he joined his fellow priests in "playing cards, drinking. . . ." But during the first year he was suddenly frightened. While he was administering the Mass he began to doubt whether the bread and the wine were actually being changed into the flesh and blood of Christ. First he considered these thoughts the whisperings of Satan; but he was unable to free himself through "sighings, prayers, and confessings." We conclude, therefore, that Menno Simons was not entirely free of influences from a movement which had become quite strong at that time in the Netherlands and whose adherents were known as Sacramentists.

The Sacramentists denied the actual presence of Christ in the Lord's Supper, i.e., Transubstantiation. This thought was first advocated publicly by Cornelis Hoen. The Sacramentists were promoters of a reform movement in the Low Countries advocating the removal of abuses in the Catholic Church and a return to a Biblical Christianity, although they were not specifically "Lutheran" or "Reformed." This Sacramentist movement became the seedbed for the message proclaimed by Melchior Hoffman and his evangelists when they penetrated the Low Countries from Emden in 1530. Hoen's views regarding the Lord's Supper were published in Switzerland by Zwingli at the very time that Menno was entertaining doubts.

After Menno had been tormented for about two years by his doubts he finally turned to the Bible and searched it for help on his particular problem. "I did not get very far in it before I saw that we had been deceived," is Menno's summary of the result of his search. In the Scriptures he found certainty regarding the Lord's Supper. He found that the Sacramentist view, which interprets the meaning of the Lord's Supper as being symbolic, was the Biblical one. Now he was torn between two authorities: the Bible and the church. Thus far he had avoided the use of the Bible, for he saw that the Bible had taken Luther, Zwingli, and others out of the Catholic Church; now he was on the same path. Which of the two authorities would win? He wanted to be loyal to both. In the meantime Menno found help by reading certain writings of Luther, who taught him that the Scriptures should have the first place. Luther also taught him that if violations of the tradition of the Catholic Church have a Biblical basis they can not lead to eternal death. He may have read Luther's Von der Menschenlehre zu meiden . . . (Krahn, 43). Gradually the Scriptures became the authority for Menno, and the source of his sermons. Soon Menno became known as an "evangelical preacher," yet he complains that in those days "the world loved him and he the world." Thus Menno, influenced by the Sacramentists and Luther, began to place the Scriptures above the authority of the church.

Melchior Hoffman, a lay preacher and follower of Luther, had traveled on long journeys as far as Baltic regions. In Strasbourg he came into contact with the Anabaptists and was baptized there in 1530, apparently not by the Swiss Brethren nor by the group represented by Pilgram Marpeck. During the same year he introduced believers' baptism in Emden, East Friesland, where he found the soil well prepared by the Sacramentist movement. As the symbolic meaning of the Lord's Supper had become the center around which its followers gathered, so now believers' or adult baptism became the point around which many Sacramentists and sympathizers of the Reformation gathered. Jan Volkerts Trypmaker, a follower of Hoffman, who had been baptized by him, baptized Sicke Freerks Snijder in Emden. The latter then went to Leeuwarden, the capital of the Dutch province of Friesland, where he soon died a martyr's death, being executed because of his "re-baptism." Menno, who lived near Leeuwarden, heard about this event. "It sounded strange to me," says he, "to hear of a second baptism." This made a deep impression on him, although the idea as such was probably not entirely new to him (Krahn, 24). The thought of believers' baptism was now constantly in his mind. He "searched the Scriptures diligently and considered the question seriously but could find nothing about infant baptism." He also consulted his colleague, the Church Fathers, Luther, Bucer, and Bullinger. In their writings he found various reasons given for infant baptism, in which "each one followed only his own mind." He saw himself deceived by all on the question of baptism. The Scriptures, in which he found no definite reference to infant baptism, convinced him that believers' baptism was the true Christian practice. By 1531 he was thoroughly convinced that believers' baptism was Scriptural.

This, however, did not yet cause Menno's withdrawal from the Catholic Church. Instead he accepted a call to become the pastor of his home church at Witmarsum, where he remained until he joined the Anabaptists in 1536. This step may in part be explained by the course which the Anabaptist movement was taking at this time. Hoffman had placed great emphasis on prophetic visions and the Second Coming of the Lord, but under the pressure of persecution he ordered a cessation of baptism for two years (1531-33). After he had been imprisoned in Strasbourg in May 1533 the Anabaptist movement of the Low Countries came under the influence of persons who exploited the chiliastic aspect of the Hoffmanite teaching, and threw off Hoffman's restriction on baptizing. Jan Matthijsz van Haarlem, Jan van Leyden, and others like them became prominent leaders. Aided by the results of the severe persecution they transformed a part of the peaceful Biblical Anabaptist movement into a militant Old Testament "Israel," each citizen of which was expected to help Christ usher in the millennium, which Hoffman had prophesied would start in Strasbourg, and which they variously prophesied to come at Münster, Amsterdam, and other places. Particularly the attempt to establish a "New Jerusalem" at Münster in 1534-35 affected the course and future of Anabaptism. Menno Simons, although convinced that the Catholic Church was in need of a reformation, also realized that the Melchiorite movement, which had started well with a reformation program, had now accepted some very unchristian principles and practices. Publicly from the pulpit, and privately, he denounced its evils. As early as 1532 some people in the vicinity of Witmarsum had been baptized. Menno even had some discussions with leaders of the Münsterite movement early in 1534. It is possible that among the men with whom he debated was Jan van Geelen, who organized an armed defense at the Oldeklooster near Bolsward. On 7 April 1535, this group was defeated; among those who lost their lives were Peter Simons, who may have been Menno's brother, as well as some members of his congregation. This was a turning point in Menno's life. On 25 July 1535, the "New Jerusalem" at Münster came to a tragic end. Few escaped and the leaders were tortured to death.

All this made a great impression on Menno and brought his inner life to a crisis and final decision. Had he not received some valuable insight through the Anabaptist movement in its earlier and peaceful days? Did he not know that among the Anabaptists were many with a sincere desire to live a consecrated Christian life? What had he done to prevent this tragic development through which so many were misled, although it was said that he "could silence these persons beautifully"? He now states, "The blood of these people, although misled, fell so hot upon my heart that I could not stand it, nor find rest in my soul.... I saw that these zealous children, although in error, willingly gave their lives ... for their doctrine and their faith. And I was one of those who had disclosed to some of them the abominations of the papal system. But I continued in my comfortable life and acknowledged abominations simply in order that I might enjoy physical comfort and escape the Cross of Christ.

"Pondering these things my conscience tormented me so that I could no longer endure it.... If I continue this way and do not live agreeably to the Word of the Lord..., if I through bodily fear do not lay bare the foundations of truth, nor use all my powers to direct the wandering flock who would gladly do their duty if they knew it, to the true pastures of Christ -- Oh, how shall their shed blood, shed in the midst of transgression, rise against me at the judgment of the Almighty and pronounce sentence against my poor, miserable soul!"

Menno continues his account by stating that his "heart trembled within" him and that he "prayed to God with sighs and tears that He would give" him, "a sorrowing sinner, the gift of His grace" and create within him "a clean heart and graciously through the merits of the crimson blood of Christ forgive" his "unclean walk..." and bestow upon him "wisdom, Spirit, courage ... so that" he might "preach His exalted adorable name and holy Word in purity, and make known His truth to His glory."

Thus the gradual acceptance of the evangelical truth and the willingness to take upon him the "cross of Christ" came to Menno in the crucial days of the disastrous end and defeat of the radical Melchiorites at Bolsward and Münster. He was challenged and found the courage to become the shepherd of the flock without a leader. For some nine months after the defeat at Bolsward in April 1535, he preached "the word of true repentance" more openly from his pulpit, "pointing the people to the narrow path, reproving all sin and wickedness, adultery, and false worship," but he also presented "the true worship,... baptism and the Lord's Supper, according to the doctrine of Christ," to the extent that he had at that time received from God insight and grace (Writings, 670f.).

This Menno did, not only in preaching from his pulpit and in personal contact with the people, but also through a writing which was to be the first of many. Jan van Leyden, who had assumed the blasphemous role of a "Second David" of the "New Jerusalem" at Münster, was the reason for this writing entitled The Blasphemy of Jan van Leyden. The pamphlet, which was not printed until 1627, was written after the defeat at Bolsward but before the defeat of Münster, with the intention of publication. But Münster collapsed, and Menno left the Roman church; hence the urgency and possibility of having it published diminished (Writings, 33).

After nine months of the more dedicated and open presentation of his views, Menno's position must have become known. This endangered his life, and so he quietly renounced all "worldly reputation, name and fame," infant baptism, easy life, and "willingly submitted to stress and poverty under the heavy cross of Christ." He left his home community and parish, likely by night, to start an "underground" life. According to available information this was most likely in January 1536 (Krahn, 35). For a year he probably found shelter in the province of Groningen, at times crossing the border into East Friesland. He "sought out the pious" and found "some who were zealous and maintained the truth." He dealt with the erring and "reclaimed them from the snares of damnation and gained them to Christ." Thus we find Menno continuing his labors as a voluntary underground evangelist. In addition to this work he was also studying the Word of God and writing pamphlets to strengthen and guide those in need of spiritual help and to win those in danger of losing their evangelical faith. Some of his writings he probably had started in Witmarsum, such as "The Spiritual Resurrection" (Van de Geestlijke Verrijsenisse, published ca. 1536) which was soon followed by "The New Birth" (De nieuwe Creatuere, ca. 1537) and "The Meditations on the Twenty-Fifth Psalm" (Christelycke leringhen op den 25. Psalm, ca. 1538). One of the most important writings was the Foundation Book (Dat Fundament des Christelycken leers, published 1539-40). The contents of these writings reveal that Menno had found the foundation and salvation in Jesus Christ and that he was challenging his readers to accept Christ and become His disciples.

While Menno was seeking out the pious and studying and writing in seclusion, he soon became known among the Anabaptists as a capable and devoted leader. One day "some six, seven, or eight persons" came to him who were of "one heart and one soul" with him, "beyond reproach as far as man can judge in doctrine and life, separated from the world after the witness of Scriptures and under the cross, men who sincerely abhorred not only the sect of Münster but the cursed abomination of all other worldly sects." They prayerfully requested Menno in the name of "those pious souls who were of the same mind and spirit" that he should make "the great sufferings and need of the poor oppressed souls" his concern, since their hunger was so very great and the faithful stewards so few. They urged him to use the talents which he had received from God in His vineyard (Writings, 671).

When this request to become an elder or bishop of the scattered Anabaptists came to Menno he was again greatly troubled. He realized that his talents were limited, that on one hand he was weak by nature and timid by spirit, and that on the other hand the wickedness and tyranny of the world was great; yet he saw a great hunger and need among the God-fearing, pious souls who "erred as do harmless sheep which have no shepherd." The delegation and Menno agreed to pray about this matter for a season. When they came again Menno surrendered his "soul and body to the Lord ... and commenced in due time ... to teach and to baptize, to till the vineyard of the Lord,... to build up His holy city and temple and to repair the turnble-down walls" (Writings, 672).

This marks the call and the assuming of the office of an elder by Menno Simons. When his baptism took place is not known. It is possible that this occurred while he was still at Witmarsum during the time that he was publicly preaching "the true baptism and the Lord's Supper." But it is more likely that he was not baptized upon confession of his faith until he left Witmarsum. A Catholic priest preaching believers' baptism publicly and also receiving a second baptism could not remain unnoticed by the authorities even in a little village like Witmarsum. This consideration makes us inclined to believe that he was baptized soon after his withdrawal from the Catholic Church in January 1536.

Much effort has been made to determine where Menno Simons lived after he left the Catholic Church early in 1536 (see Frerichs, 1 ff.; Vos, 64 ff.; Krahn, 32 ff.). Menno himself wrote in 1544 that he "could not find in all the countries a cabin or hut in which my poor wife and our little children could be put up in safety for a year or even half a year" (Writings, 424). This was his fate from 1536 until 1554. During the first years Menno probably spent most of his time in the Dutch province of Groningen. However, he could hardly stay anywhere for any length of time. Tjaard Renicx of Kimswerd in the province of Friesland was executed at Leeuwarden in January 1539 because he had sheltered Menno. Syouck Haeyes confessed in 1542 that he had heard a sermon by Menno outside Leeuwarden. An official document of Leeuwarden of 19 May 1541, states that Menno, one of the principal leaders, made it a practice to come to the province of Friesland once or twice a year, winning many followers.

On 7 December 1542, one hundred guilders were offered by the authorities of Leeuwarden for the apprehension of Menno, who appeared by night at different places to preach and baptize. This indicates that Menno returned to his native province of Friesland at times in all secrecy but only for a short time. Menno found no permanent home during this time in any of the Dutch provinces.

Soon after his renunciation of Catholicism in 1536 Menno was also in the German province of East Friesland, where Ulrich von Dornum of Oldersum sheltered religious refugees, and according to tradition he found shelter here under Dornum's protection. However, Menno's statement must not be forgotten, that he and his family never found a place where they could live unmolested "for a year or even half a year." When and where Menno married his wife Geertruydt is not definitely known. In 1544 he spoke of their "little children." Peter Jansz confessed on 14 June 1540 that Menno had baptized him at Oldersum"about four years ago" (Vos, 243). This shows that Menno traveled early and extensively after his withdrawal. It will be shown later that he soon became well known in East Friesland. However, it is doubtful that he ever met Ulrich von Dornum or was a guest in his home during Dornum's lifetime, since the latter died early in the spring of 1536 (Ohling, 49). If this did occur, Menno had to proceed directly from Witmarsum to Oldersum. Ulrich was a staunch promoter of the Reformation, a friend of Karlstadt and Sebastian Franck, an admirer of Hans Denck, and a sympathizer with the Anabaptists. Two of his daughters married Anabaptists; one of them in 1551 married Christopher van Ewsum, who sheltered Menno in Groningen and whom Alba called a "principal Mennist" (Ohling, 24).

East Friesland, where Melchior Hoffman had baptized some 300 persons in the city of Emden, became a refuge for the Sacramentists of the Low Countries and other persecuted minorities. Even Karlstadt found shelter on the estate of Ulrich von Dornum. Menno, as has been said, also found his way to East Friesland soon after his withdrawal from Witmarsum. At this time John a Lasco was the superintendent of the East Friesland churches under the ruler, Countess Anna of Oldenburg.

In January 1544 Menno had a theological discussion with a Lasco. The objective of this discussion was to win Menno and his followers to the Reformed Church. That Menno was called upon to represent the Mennonites makes it clear that he was known in East Friesland as their spokesman. Anna, personally a tolerant ruler, was compelled by the emperor to do something about the numerous religious groups found in her domain. She consented to expel those which a Lasco would designate as "heretical." The latter's first objective was to win those who were spiritually closest to his own views. The discussion was held on 28-31 January 1544 when the articles pertaining to the Incarnation, baptism, original sin, justification, and the call of ministers were discussed. Although the two men did not agree concerning all articles, Menno and his followers were dismissed by a Lasco in a friendly manner. Menno had promised to present a written confession regarding the Incarnation, and he now wrote "in a secluded place" under the title, A brief and clear confession and scriptural declaration concerning the Incarnation.... A Lasco had it printed in 1544 without Menno's knowledge or consent and used it against him. The following decree of Countess Anna in 1545 announces that the followers of David Joris and Batenburg should be "corrected on their neck" (executed) if they would not leave the country. The "Mennisten," however, were to be examined by the superintendent, and if they did not surrender were to leave the country. The term "Mennisten" designating followers of Menno appeared for the first time in any official document in the 1545 decree. This again, as well as the fact that Menno left East Friesland before this announcement was published, indicates that he was well known in this area as an Anabaptist leader (Krahn, 59 ff.).

In May 1544 Menno went to the Lower Rhine region, to the area of Cologne and Bonn. A Lasco wrote to Hardenberg on 26 July 1544 that Menno was in the bishopric of Cologne, where he was "misleading" many. This area had long been a fertile ground for the evangelical and Sacramentist movement. Menno was also successful there, and associated with the Anabaptist leaders Zyllis and Lemke. Matthias Servaes, who died a martyr's death here, refused at any cost to "renounce" the principles for which Menno Simons stood. This indicates the degree of success of Menno's work in this area.

Menno's activities here coincide with the last years of the bishopric of Archbishop Hermann von Wied of Cologne, who had to give up his position in 1546 because he was promoting an evangelical reformation in the Catholic Church. Hardenberg, an active reformer of this area, influenced by a Lasco, interfered with Menno's activities. Menno was also in all probability active at the following places in the Maas River region: Vischersweert, Illekhoven, and Roermond. Several martyrs of this area testified that they had heard sermons by Menno in 1545. Under the rigid Catholic rule of the successor of Hermann von Wied in 1546, Menno had to leave this district. He now proceeded to the province of Schleswig-Holstein.

In the fall of 1546 Menno attended a discussion at a country place near Lübeck with the followers of David Joris, led by the latter's son-in-law Nicolaas Meyndertsz van Blesdijk. Joris himself had left Emden for Basel early in 1544. David Joris, an extreme left-wing Anabaptist of the Law Countries, who had been ordained elder by Obbe Philips in 1535, before Menno, had never been in full harmony with the peaceful Anabaptist representatives such as Dirk and Obbe Philips or Menno Simons. He placed too much emphasis on personal visions and "revelations" without checking them against the Scriptures. Menno and his followers opposed all revolutionary and mystical fanaticism. In addition to their spiritualistic conception of the Scriptures, Menno opposed the Jorists for considering it unnecessary to baptize or to organize churches during the time of persecution. Menno was supported in this discussion by the elders Dirk Philips, Leenaert Bouwens, Gillis van Aken, and Adam Pastor, and the group excommunicated Joris.

Another question arose when it became apparent that Adam Pastor, a former priest, who had been ordained ca. 1542 as an Anabaptist elder by Menno and Dirk, turned heretical in his Christological views. At a conference at Emden in 1547 no agreement could be reached. Meetings at Goch (1547), the Lower Rhine, and Lübeck (1552) followed. Since no agreement could be reached, Pastor was excommunicated at once. Pastor apparently deviated from the others on a number of other questions also, such as church discipline and relationship to government. He was more liberal than the group. His views regarding Christ differ considerably from those of Menno. Whereas Menno emphasized the deity of Christ, Pastor emphasized His humanity. Pastor believed that Jesus became the Saviour because God endowed Him and ordained Him for this task; but in essence He was not divine or equal with God. Menno on the other hand also deviated somewhat from the accepted orthodox creed, which sets forth the divine and the human nature as equally present in Christ, in stressing His divinity above His humanity. His peculiar conception of the Incarnation of Christ he had adopted from Melchior Hoffman. It became for him an essential part of his concept of the church. Christ in the Incarnation passed through Mary's womb like a ray of sunshine through a glass of water without taking on any of her "sinful flesh." Only thus, he claimed, could the Saviour be perfect, and only because of this can the work of His salvation, the church of Jesus Christ, be perfected.

Menno's traveling schedule indicates that he spent some time during the years after 1546 at Lübeck, Emden, the Lower Rhine, Leeuwarden, Danzig, etc. He still had no permanent home, although it is likely that his family did not accompany him on these trips of a shorter duration. In April 1549 Menno stayed overnight at the home of Klaas Jans, who was executed on this account at Leeuwarden on June 1. During the same summer he spent some weeks with the "Elected and Children of God in the Country of Prussia," as becomes apparent from a letter which he addressed to these believers on 7 October 1549. This indicates not only that the Anabaptists of the Low Countries had spread as far as Danzig, but also that Menno's guidance, counsel, and authority were needed to iron out some difficulties which had risen. His co-worker Dirk Philips became the first elder of the Danzig Mennonite Church. It is possible that Menno's visit to the Anabaptists in Danzig and Prussia was not limited to this one occasion, although definite information lacking.

In search of a field of labor and a refuge Menno had moved from the Low Countries to the province of East Friesland and was now on his way to Mecklenburg. He no doubt resided for some time in the Hanseatic city of Wismar. He was here during the winter of 1553-54 when a group from a Lasco's church arrived by boat from London as a refugee congregation. Since the Lutheran city of Wismar did not welcome this Reformed group, the Mennonites went out over the frozen ice of the harbor to the boat to meet them and to provide them with help and aid. This led to a religious discussion. On 6 February 1554, the a Lasco group met with Menno and his followers, having invited Marten Micronius of Emden to serve as their man. The Incarnation was again among the topics discussed. The discussion ended in hostility, with the Mennonites accusing the Reformed of publishing a list of the Mennonites located in Wismar which had speeded up their expulsion from the city. An exchange of writings between Menno and Marten Micronius resulted from this discussion.

Before this occurred Menno and certain other elders met in Wismar for a conference, at which they agreed on certain rules of church practice and discipline known as the Wismar Articles (1554). These articles deal primarily with the relationship between partners in a mixed marriage, i.e., believer and unbeliever, the matter of appealing to a court, and nonresistance. During this time Menno also wrote and published his book against the accusations of Gellius Faber, entitled Een Klare beantwoordinge ... (Reply to Gellius Faber) which was published in the Anabaptist print shop at Lübeck in 1554. In this, the longest book that Menno produced, can be found the account of his "Conversion" or the "Renunciation of the Church of Rome," which he presented in order to defend the calling of the Anabaptist ministers.

On 11 November 1554 the city council of Wismar decreed that all Anabaptists were to leave the city. Menno had already left during the summer and gone to Lübeck. He and his followers proceeded together to the town of Oldesloe in the province of Holstein. In the vicinity of this town Bartholomeus von Ahlefeldt had since 1543 been gathering oppressed Anabaptists on one of his large estates, called Wüstenfelde (desert field). Here at last Menno found shelter and protection. His printer began to print his books, and Menno took the opportunity to revise his early editions and write several new books. Although von Ahlefeldt was often challenged to expel the Mennonites he remained their protector, having learned to appreciate them when he was in Holland.

The Mennonites aimed at nothing less than the establishment of a true Christian and apostolic church. With Paul they were determined to present to Christ His bride without spot and wrinkle and to keep themselves pure and clean as far as the world around them was concerned and also to keep the world out of the church. They were doing this through church discipline, using the ban and avoidance. Questions regarding the application of church discipline led to controversies. Menno had meetings with his fellow workers in Emden, Francker, and Harlingen. Dirk Philips and Leenaert Bouwens favored a rigid application of church discipline. Others were lenient. Menno mediated between the two extremes. Menno made his last trip to his home province, Friesland, in 1557 to settle a dispute over this question. But in vain. This matter was to occupy the minds and hearts of the Dutch Mennonites for at least another century. After his return he wrote to a friend, "If the omnipotent God had not preserved me last year as well as now, I would already have gone mad. For there is nothing upon earth which my heart loves more than it does the church, and yet I must live to see this sad affliction upon her" (Writings, 1055). Certain reports indicate that Menno was won over by the more rigid church disciplinarians toward the end of his life.

Through Zyllis and Lemke, Menno's friends and co-workers of the Lower Rhine area, the question of church discipline was presented at a large conference of South German Anabaptists which met at Strasbourg in 1557. Some 50 representatives of congregations in various South German countries, such as Moravia, Switzerland, and Alsace, were present. The assembled elders sent an appeal to Menno and his co-workers not to go to extremes in the matter of ban and avoidance, through which even family life was disrupted. Menno and Dirk Philips responded in writing, defending the more rigid position. Menno now emphasized that the heavenly marriage between Christ and the soul is more important than the relationship of man and wife in the earthly marriage. This controversy saddened the last days of his life.

During his last years Menno was crippled. The earliest portraits show him with crutches. His wife preceded him in death, although it is not known when she died. The children included at least two daughters and a son Jan. The son probably also preceded the father in death. One of the daughters gave some information about Menno to the historian Pieter Jans Twisck. According to all available information Menno died at Wüstenfelde on 31 January 1561, 25 years after his withdrawal from the Catholic Church. He was buried in his own garden. The Thirty Years' War destroyed the estate on which the Anabaptists had settled, so that the exact location of the grave is no longer known. In 1906 a simple stone was erected at the approximate place, which was popularly known as the "Menno field." Not far from it the Menno Linden, supposedly planted by Menno himself, and the Menno House, in which his books were supposedly printed, still stand.

Menno Simons was a Biblicist in the truest and best meaning of the word. He turned away from tradition and became Bible-centered in all his beliefs and practices. Once he had turned to the Bible, he took it for the Word of God and made it the cornerstone of all his work. His writings are filled with Bible quotations. His approach to the Bible differs from that of the other reformers. It is above all Christ-centered. Every book and every little pamphlet he wrote have on the front page the motto, "For other foundation can no man lay than that is laid, which is Jesus Christ" (1 Corinthians 3:11). Christ-centeredness marks his theology and the practices he derived from the Bible. Discipleship (Nachfolge) or a fruitful Christian life were very strongly emphasized. But this emphasis on true Christian living does not take place in a vacuum or as a matter merely between the individual and his God, but rather within the congregation, the church of Christ. Menno's faith is therefore not only Christ-centered but also church-centered: his chief concern was the achievement of the true church of Jesus Christ or the body of Christ. Again and again he refers to 1 Corinthians 12:13, 25-27, and Colossians 1:18-24. The prerequisites for church membership according to Menno are regeneration and willingness to bear the cross of Christ. These two are inseparable. Discipline was as natural in the church of Menno Simons as any normal function of the healthy body.

Behind these views lie first of all Menno's personal experience in the Catholic Church, and the experience which he had with the Reformers and Münsterites. With Luther he rejected the Catholic Church, which did not preach justification by faith, but he also had to reject the Lutheran Church because of its one-sided emphasis on "faith alone." On the other hand he could not accept the radical movement which attempted to usher in the kingdom of God by force. Instead he developed a theology of martyrdom, of suffering for God.

Menno's significance lies in the fact that he prevented the collapse of the northern wing of the Anabaptist movement in the days of its greatest trial and built it up on the right Biblical foundation. He did this as its leader, speaker, and defender, through his preaching as he journeyed from place to place, and through his simple and searching writings. Particularly the Foundation-Book did much to restore the original Anabaptist concepts and principles, which were in grave danger of being lost. His writings were effective not so much because of their superior and logical qualities as a theological system, but because behind them stood a man formed according to the Scriptures who sincerely and honestly wanted to give all for the Christian church and the glory of God. Through Menno's courageous and devoted life a distinctive witness in the Reformation movement, representing a Christian brotherhood and a Christian way of life, was preserved, which have meanwhile become quite generally recognized as an integral part of Protestantism and include such basic principles as separation of church and state, freedom of conscience, voluntary church membership, democratic church government, holy living, and the Christian peace witness in a world of strife.

The questions pertaining to the linguistic peculiarities, the editions and printers of Menno's writings have found some interest among scholars; and a considerable amount of investigation has been made. G. E. Frerichs wrote a detailed article on "Menno's taal" (Menno's Language) (DB 1905). He concluded that Menno's first writings were linguistically colored by the language of the place in which he was living, and which he (Frerichs) thought to find in the province of Groningen, called "Ommelanden." Karel Vos calls the writings and the linguistic coloring of this period (1537-41) an Oosters gekleurd dialect, meaning with "an eastern coloring." The term Oosters (eastern) is, however, relative. "Eastern" is viewed from the standpoint of the province of Holland, which was the leading one in the economy and the culture of the Netherlands for a long time, and whose language became the standard. A slight deviation from its language under the influence of linguistic pecularities; of the regions east and northeast of the province of Holland is designated as an Oosters gekleurd dialect. Such peculiarities in the writings of Menno Simons, which are characteristic of the province of Groningen, are designated by Vos as Oosters gekleurd.

Later, when Menno Simons was living in East Friesland and Holstein, his language was necessarily adapted to the language of this country since he was printing primarily for the people of that territory. Vos refers to the language in which Menno wrote and printed his books in East Friesland and the Hanseatic cities as the Oosters language (not only an Oosters gekleurd dialect). Menno even revised his earlier Dutch writings and had them reprinted at Lubeck, Oldesloe, and Wüstenfelde in the Oosters language. The later writings printed first in Oosters were translated into the Dutch for use in the Netherlands proper. The question of the linguistic peculiarities in the various editions and writings of Menno Simons deserves a more thorough investigation and would be one of the most significant tasks in preparing a scholarly edition of Menno's writings. The following is merely a brief outline of Menno's printers and printing facilities as far as they can be determined at this time.

It is very difficult to determine where and when Menno's early writings were printed and who the printers were. Jan Claesz was beheaded 19 January 1544 because he had 600 copies of Menno Simons' books printed at Antwerp. He sold 200 of them in the province of Holland and sent the rest to Friesland. These books must have been some of Menno's earliest writings. A little information is, found in the copy of the Foundation-Book (1539-40) in the British Museum, which has an entry by Johan Enschede of Haarlem pertaining to the type used in the book. Nijhoff-Kronenberg (Ned. Bibliographie I, p. 540) states that this book and Menno's Voele goede leringhen op den 25. Psalm (ca. 1538) and Een corte vermaninghe . . . van de wedergeboorte (ca. 1537) were both printed in the same print shop. It should be possible to discover more details about the print shop by the type that was used (see also Vos, 296). It is likely that others of Menno's books were published in East Friesland during the time he was living there. To what an extent, if at all, Nicolaes Biestkens of Emden, who printed for the Mennonites, printed Menno's writings, should be investigated. Probably no writings of Menno appeared between 1542 and 1551. After 1551 Menno and the Anabaptists had a printer at Lübeck. When the underground print shop here was discovered, the authorities found ten tons of books. The printer then moved from Lubeck to Oldesloe, and in 1554 to Wüstenfelde, where he continued to function as Menno's printer. At this time an Oosters edition of the Foundation-Book appeared with a certain "B. L." as printer. All of Menno's writings, both new and revised editions, appeared now in Wüstenfelde in rapid succession. Von Ahlefeldt protected Menno and his printer, B. L., whose full name is not yet known, against all attacks. In 1558 a Dutch edition of the Foundation-Book appeared, probably in Wüstenfelde (BRN VII, 253). The printer must have continued his work even after Menno's death in 1561. In 1562 another Dutch edition of the Foundation-Book appeared. In 1616 an unchanged Dutch reprint of the 1539-40 edition was published.

The writings of Menno Simons have been published more often than the writings of any other Anabaptist leaders. The Foundation-Book was translated into German in 1575. The first large collection appeared in Dutch as Sommarie (1600-1) which was followed by the Opera ofte Groot Sommarie (1646) and the Opera Omnia Theologica (1681). In America the first complete edition of Menno Simons appeared in 1871 in English and in 1876 in German. In 1956 a new enlarged English edition, the first practically complete edition in any language, was published. An urgent task in Mennonite research would be to prepare a scholarly edition of Menno's writings, in which the various early and later editions and translations would be fully taken into consideration, similar to the edition of Dirk Philips' writings published in Volume X of the BRN.

Turning to the research pertaining to the life, work, and beliefs of Menno it must be said that no other Anabaptist leader has been the subject of as many biographies as Menno. All major aspects of his life, times, and activities, have been investigated, primarily by Dutch, but also by some German scholars. Much of the biographical information was published in the Doopsgezinde Bijdragen (1861-1919). A. M. Cramer wrote the first significant biography (1837). J. G. de Hoop Scheffer, Christiaan Sepp, and G. E. Frerichs published much biographical information in Doopsgezinde Bijdragen. The first most complete scholarly biography of Menno was produced by Karel Vos (1914) based on extensive archival research. W. J. Kühler published his findings along these lines in his history of the Dutch Mennonites during the 16th century (1932). In the German language early biographies appeared, written by C. Harder (1846) and B. C. Roosen (1848). A recent German biography, with a theological interpretation of the views of Menno and his followers, was written by Cornelius Krahn (1936). In America John Horsch presented the only full-length English biography (1916).

The Amsterdam Mennonite Library has an authentic letter written by Menno Simons himself; it is undated and is addressed (after 1554) to a widow. This letter is the only extant manuscript in Menno's handwriting. It was printed, with somewhat modified spelling, in Opera Omnia, page 336.

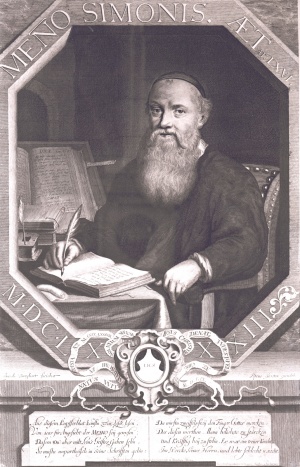

None of the portraits of Menno, circulating since the early 17th century, can be considered historically true. The most acceptable one is the engraving made about 1608 by Christoffel van Sichem. Recently the Dutch artist Arend Hendriks made a beautiful etching of Menno. -- Cornelius Krahn

1990 Article: Current Research

Research in the 20th century on Menno Simons is summarized in three basic articles: the article by Cornelius Krahn (above), the 1962 article "Menno Simons Research (1910-1960)," also by Krahn, in No other foundation (North Newton, 1962), 65-76, and in an article by Walter Klaassen, "Menno Simons research, 1937-1986," Mennonite quarterly review 60 (1986), 483-96. To these should be added the papers read in Amsterdam at the Menno Simons Colloquium in 1986, published in Dutch in Doopsgezinde Bijdragen, n.r. 12-13 (1986-1987), and in English in Mennonite quarterly review 62 (July 1988).

Scholars have long agreed that Menno was not the founder but the organizer of Dutch Mennonitism; beyond that almost every question about him has been a matter of debate from his own time to the late 20th century. His contemporaries, both supporters and opponents, debated vigorously with him. Only a small group, which soon died out, used his name, though it came into broader, and eventually global use. In the 1980s his writings are being studied with new respect, also by non-Mennonites, perhaps because the real Menno is emerging in place of the hero Mennonites wanted and needed.

It is now generally agreed that Menno initially was a Melchiorite, that is, a follower of Melchior Hoffman, and that he called the Münster Anabaptists "brothers" but broke decisively with them over the use of force to bring in the kingdom of God. Studies continue on his educational background and intellectual ability. On the former G. K. Epp reports Praemonstratensian roots in Mennonite images (1980), ed. Harry Loewen. Cornelis Augustijn is convinced that Menno had a "fair" education influenced by the spirit and thought of Erasmus, that be was a very formidable debater and that "the essential features of his theology may be traced to Erasmus" (MQR 60 [1986], 497-508). Irvin B. Horst had traced this influence earlier and came to a similar conclusion, but stated it less emphatically in Erasmus, the Anabaptists and the problem of religious unity (Haarlem, 1967). S. Voolstra and W. Bergsma, eds., and trans., Huyt Babel ghevloden, in Jeruzalem ghetogen: Menno Simons' verlichting, bekering en beroeping, Doperse Stemmen, 6 (Amsterdam: Doopsgezinde Historische Kring, 1986), and Voolstra in MQR 62 (July 1988) offer additional interpretation of Menno's biographical background and motivation. Older images of the simple Menno who was "slow moving... not easily stirred and changed... even his small corpus of writings is often boringly repetitious" are reaffirmed by John R. Loeschen in The divine community (1981), 67, even though the volume is a comparison of Luther, Menno, and Calvin on the doctrine of the Trinity and Menno received fair treatment.

No single organizing center of Menno's thought has been identified but there is general agreement that he moved from a stress upon conversion early in his career to a gradually increasing emphasis on the church which, in turn, led to greater emphasis on discipline. The vision of a pure church also led Menno to stress the heavenly origin of the human Christ, a doctrine which caused much controversy already in his time, but has more recently been affirmed as a vital part of Menno's understanding of salvation and the possibility of believers becoming Christlike (S. Voolstra, Het Woord Is Vlees Geworden (1982). Menno may, at times, sound like a docetist, but he was not one. So also Menno's stress upon a return to the spirit and norm of the church in the Bible (restitutionism) as a way to achieve a pure church has often been identified (Jaroslav Pelikan, The Christian tradition, 4 [1984), 313-22). In an earlier attempt to refute works-righteousness J. A. Oosterbaan identified Menno's understanding of grace with the doctrine of creation itself ("Grace in Dutch Mennonite theology," A legacy of faith, ed. C. J. Dyck [1962], 69-85). Work continues on Menno's political theory. As Menno grew older he came to reject capital punishment, but continued to defend the possibility of a Christian magistrate. Some scholars find a strong anticlericalism in his writings (e.g., H.-J. Goertz, "Der Fremde Menno Simons: Antiklerikale Argumentation im Werk eines melchioritischen Täufers," Menn. Geschbl., 42 [1985], 24-42).

Menno's original works are now available on microfiche. In 1988 work had begun in Amsterdam on a text-critical edition of all of Menno's writings. -- Cornelius J. Dyck

Bibliography

Sources

Menno Simons. The Complete Works. Elkhart, Ind, 1871.

Menno Simons, The Complete Writings of Menno Simons, c. 1496-1561, trans. Leonard Verduin, ed. J. C. Wenger. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1956.

Menno Simons. Opera Omnia Theologica. Amsterdam, 1681.

Menno Simons. Die vollstandigen Werke. Elkhart, IN, 1876.

Menno Simons. Die vollstandigen Werke. Baltic, Ohio, 1926.

Alenson, Hans. "Tegen-Bericht op de voor-Reden want groote Martelaer Boeck." 1630, in Bibliotheca Reformatoria Neerlandica VII. The Hague, 1910.

Goverts, E. F. "Archivstücke aus dem Reichsarchiv Hansborg." Ztscht d. Zentralstelle für Niedersächsische Familiengeschichte. Hamburg, 1923, No. 5.

Hoop Scheffer, J. G. de. Inventaris der Archiefstukken berustende bij de Vereenigde Doopsgezinde Gemeente te Amsterdam 1, Nos. 241 f., 257-60, 323, 343, 356, 367, 417, 463, 617, 619 f., 631, 640.

I. H. V. P. N. Het beginsel en voortganck der geschillen, scheuringen, en verdeeltheden onder de ... Doopsgesinden.

Obbe Philips. "Bekenntenisse . . ." Amsterdam, 1584 in Bibliotheca Reformatoria Neerlandica VII.

Biographies

Bastian, F. Essai sur la vie et les ecrits de Menno Simons. Strasbourg, 1857.

Bender, H. S. and J. Horsch. Menno Simons' Life and Writings. Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House, 1936.

Bornhäuser; Christoph. Leben und Lehre Menno Simons': ein Kampf um d. Fundament d. Glaubens (etws 1496-1561). Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1973.

Cramer, A. M. Het leven en de verrichtingen van Menno Simons. Amsterdam, 1837.

Cramer, S. "Menno Simons." In Realencyclopädie für Protestantische Theologie und Kirche, 3rd ed. Leipzig.

Cramer, S. "Menno's Leven." Doopsgezinde Bijdragen (1904).

Fleischer, F. C. Menno Simons (1492-1559). Amsterdam, 1892.

Harder, C. Das Leben Menno Symons. Konigsberg, 1846.

Hoop Scheffer, J. G. de. "Eenige opmerkingen en mededeelingen bar Menno Simons." Doopsgezinde Bijdragen (1864, 1865, 1872, 1881, 1889, 1890, 1892, 1894).

Horsch, John. Menno Simons, His Life, Labors and Teachings. Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House 1916.

Keeney, William Echard. The Development of Dutch Anabaptist Thought and Practice From 1539-1564. Nieuwkoop: B. de Graaf, 1968.

Krahn, Cornelius. "The Conversion of Menno Simons: a Quadricentennial Tribute." Mennonite Quarterly Review 9f. (1935-36).

Krahn, Cornelius. Menno Simons. Karlsruhe, 1936.

Kühler, Walther. Geschiedenis der Nederlandsche Doopsgezinden in de Zestiende Eeuw. Haarlem, 1932.

Limburg, Rob. "Menno Simons, de Herder der verstrooide Kudos. In Cultuurdragers in bewogen dagen. The Hague, n.d.-1941: 112-53.

Poettker, Henry. "The Hermeneutics of Menno Simons: an Investigation of the Principles of Interpretation Which Menno Brought to his Study of the Scriptures." Th.D. diss, Princeton U., 1961.

Reimer, Johannes. Menno Simons: ein Leben im Dienst. Lage: Logos Verlag, 1996.

Smith, C. Henry. Menno Simons, an Apostle of the Nonresistant Life. Berne, IN, ca. 1936.

Voolstra, Sjouke. Menno Simons : His Image and Message. North Newton, KS: Bethel College, 1997.

Vos, K. Menno Simons. Leiden, 1914.

Other Literature

Boekenoogen, G. J. "De portretten van Menno Simons." Doopsgezinde Bijdragen (1916).

Brune, Friedrich. Der Kampf um eine evangelische Kirche im Münsterland 1520-1802. Witten, 1953.

Catalogus der werken over de Doopsgezinden en hunne geschiedenis aawezig in de bibliotheek ver Vereenigde Doopsgezinde Gemeente te Amsterdam. Amsterdam, 1919.

Cornelis, C. A. Der Anteil Ostfrieslands an der Reformation bis zum Jahr 1535. Münster, 1852.

Crous, E. "Auf Mennos Spuren am Niederrhein." Der Mennonit 8 (1955), Nos. 10-12, and 9, Nos. 1-2.

Dalton, H. Johannes a Lasco. Utrecht, 1885.

Dollinger, R. Geschichte der Mennoniten in Schleswig-Holstein, Hamburg und Lübeck. Neumünster, 1930.

Doopsgezind Jaarboekje (1936): 40-69.

Frerichs, G. E. "Menno's taal." Doopsgezinde Bijdragen (1906).

Frerichs, G. E. "Menno's verblijf in de estate jaren na zijn uitgang." Doopsgezinde Bijdragen (1906).

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. III, 177-90.

Heins, Julian. Menno Simonis. Ein dramatisches Gedicht. Danzig, 1844.

Hoekstra, S. Beginselen en Leer der Oude Doopsgezinden, vergeleken met die van de overige Protestanten. Amsterdam, 1863.

Klaassen, Walter. "Menno Simons Research, 1937-1986." Mennonite Quarterly Review 60 (1986): 483-96.

Klaassen, Walter, et al. No Other Foundation: Commemorative Essays on Menno Simons. North Newton KS: Bethel College, 1962.

Kochs, E. "Die Anfänge der ostfr. Reformation." Jahrbuch der Geschichte für bild. Kunst und vaterl. Altertümer zu Emden 19 (1916-18): 109-273; 20 (1920): 1-125.

Mellink, A. F. De Wederdopers in de noordelijke Nederlanden 1531-1544. Groningen, 1954.

Müller, J. P. Die Mennoniten in Ostfriesland. Emden, 1887.

Müller, J. P. "Die Mennoniten in Ostfriesland." Jahrbuch ... Emden 4 (1881): 58-74, and 5 (1882): 46-79.

Ohling, G. Ulrich von Dornum ... Aurich, 1955.

Roosen, B. C. Menno Simons, den evens. Mennoniten-Gemeinden geschildert. Leipzig, 1848.

Smeding, Sibold S. "The Portraits of Menno Simons." Mennonite Life 3 (July 1948).

Smissen, H. van der. Mennostein und Mennolinde zu Fresenburg. N.p., n.d.

Unruh, B. H. Die niederländisch-niederdeutschen Hintergründe der mennonitischen Ostwanderungen. Karlsruhe, 1955.

Vos, K. "Menno Simons in Groningen." Groningsche Volksalmanak (1919): 139-46.

Wessel, J. H. De leerstellige strijd tusschen Nederlandsche Gereformeerden en Doopsgezinden in de zestiende eeuw. Assen, 1945.

Zijpp, N. van der. Geschiedenis der Doopsgezinden in Nederland. Arnhem, 1952.

Zijpp, N. van der. Menno Simonsz. Amsterdam, 1950.

Additional Information

Electronic Resources

The Complete Works of Menno Simons. Elkhart, Ind.: John F. Funk, 1871. Full Text.

Horsch, John. Menno Simons: His Life, Labors, and Teachings. Scottdale, PA: Published by the author, printed by Mennonite Publishing House, 1916. Full Text.

Menno Simons. A Foundation And Plain Instruction of the Saving Doctrine of Our Lord Jesus Christ ... Lancaster, Pa: [Boswell & M'Cleery], 1835. Full Text.

Opera omnia theologica, of, Alle de Godtgeleerde wercken, van Menno Symons... Full Text.

| Author(s) | Cornelius Krahn |

|---|---|

| Cornelius J. Dyck | |

| Date Published | 1990 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Krahn, Cornelius and Cornelius J. Dyck. "Menno Simons (1496-1561)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1990. Web. 30 Mar 2025. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Menno_Simons_(1496-1561)&oldid=160744.

APA style

Krahn, Cornelius and Cornelius J. Dyck. (1990). Menno Simons (1496-1561). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 30 March 2025, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Menno_Simons_(1496-1561)&oldid=160744.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 3, pp. 577-584; vol. 4, p. 1146; vol. 5, pp. 554-555. All rights reserved.

©1996-2025 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.