France

Introduction

France extends from the Mediterranean Sea to the English Channel and the North Sea, and from the Rhine River to the Atlantic Ocean. It is bordered by Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Monaco, Andorra, and Spain. France is the second largest country in Europe, comprising 674,843 km2 (260,558 sq mi).

The total estimated population of France in 2009, not including its overseas territories, is 62,448,977. In 2007 51% of France's population identified as being Roman Catholic, 31% identified as being agnostics or atheists, 10% identified as being from other religions or being without opinion, 4% identified as Muslim, 3% identified as Protestant, and 1% identified as Jewish.

1956 Article

Throughout the late Middle Ages France was the major center of "pre-evangelical" heretical movements; these movements, parallel in certain of their aims and principles, of whose relations with one another and with Anabaptism so little is known, from Martin of Tours to the Waldenses, embodied in varying degrees the concern for Scriptural reformation which the Anabaptists were later to apply consistently. Since, however, the debate on the relation of these movements to Anabaptism has not yet been closed, their history does not fall within the scope of this article;

The greatest centralization of royal and ecclesiastical authority in France prevented any real beginning of Anabaptism in the 16th century. Protestants themselves being a persecuted minority, the issues on which focused the break between Zwingli and the Anabaptists never came to the same degree of clarity in the French-speaking Reformation. Flanders and Alsace were both centers of Anabaptism, but were at that time not part of France, and little if anything of the original 16th-century movement existed in either of these two provinces at the time of their acquisition by France.

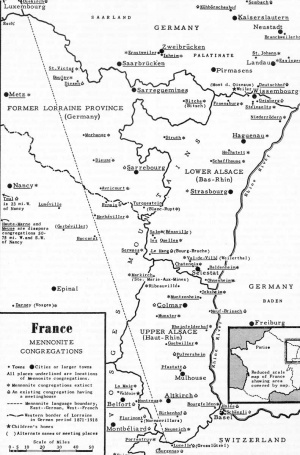

During and after the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), at the end of which Alsace became French, the movement of Mennonites into Alsace from Switzerland became important. Some went on to the Palatinate, and others remained to reclaim lands laid waste by the wars. They settled both on the plains around Colmar, where on 4 February 1660 a group of elders and ministers adopted the Dordrecht Confession of 1632, and in the valley of Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines (Markirch), where they were given citizenship and exemption from military service, against payment of a special tax. Although already in this area by 1640, they seem to have come in force especially after 1670, when a new wave of persecution broke over the Bernese Mennonites.

It is in this latter area (Markirch) that we encounter in 1696 the name of Jakob Ammann, who represented a newly arrived group of Swiss Mennonites before the Prevost of the valley with the aim of reminding the government of the privileges previously granted concerning military service. The Amish division in France seems probably to have grown from the triangular tension between the newer elements of the Markirch settlement, its parent congregations in the canton of Bern, and the older congregations of the Alsatian Rhine plain, which alone are known to have adopted the Dordrecht Confession, whose eleventh and twelfth articles do not represent Swiss Mennonite tradition. The final result of this division was that all surviving (as of 1954) congregations in France, with the exceptions of Geisberg and Florimont, and including Binningen-Holee and Courgenay-Lucelle across the Swiss border, were of the Amish branch.

For some time Mennonites in Alsace enjoyed relative liberty, being able to avoid the requirements of military service and the oath. Gradually, however, their nonconformist position, their privileges, and their general prosperity attracted the ill will of their neighbors and of the Church, and with the tightening of France's hold in Alsace there came also, in February of 1712, the order to expel all Anabaptists from Alsace, since—so ran the argument—the Peace of Westphalia (1648) had promised religious freedom only to Calvinists and Lutherans. Migration began in all directions; east and especially north into Germany, south into the principality of Montbéliard, and west through the Vosges Mountains into Lorraine. Lorraine was at that time independent under a Polish duke, and Montbéliard belonged to Württemberg and thus to Austria. The movement into Lorraine was chiefly infiltration, profiting from the relative isolation of the mountainous headlands of the Muerthe and Sarre basins. The movement to Montbéliard was, on the other hand, massive and intentionally encouraged by Count Leopold Eberhard, who sought honest farmers to manage the lands which he had acquired from his people by oppressive means. Though the state church in Montbéliard was Lutheran, this tolerance on the part of the count was purely commercial and had no basis in his Protestantism or in any ideas of religious liberty. Mennonites had no right to meet openly for worship, to intermarry with the local Lutheran population, or to acquire new members.

Their status as a "foreign body" being thus underlined, and their presence in the region being a result of Leopold Eberhard's confiscation of private lands, Mennonites were naturally not popular among the natives of the principality. Whereas the count continued to invite the Mennonites, even sending representatives to Bern to ask them to come, both the neighboring provinces, such as Burgundy, and the local populations remained opposed to the "Swiss."

Only with the Revolution of 1789 and following did Montbéliard become a part of France. The first effect of "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity" for the Mennonites was not religious liberty, but rather the opportunity given the local populations, through local revolutionary committees, to express their accumulated resentments. Both the loyalty oath and obligatory militia service became means of applying pressure. (There were even attempts in both Montbéliard and the Haut-Rhin to forbid the wearing of beards in the name of equality.) Fortunately, the higher revolutionary authorities were more understanding than the local hotheads, and the right to perform alternative service with the supply or hospital troops was generally granted, as was apparently the right to replace the oath by a pledge sealed with a handshake. Their critics raised the question whether such people could be considered as citizens. On this point the departmental government of Doubs (Montbéliard) appealed to the National Assembly, and the Comite du Salut Publique, apparently in response to this request, though not answering the question, confirmed on 19 August 1793 the right to noncombatant service. Napoleon, institutionalizing the principle of military service, allowed no exceptions for reasons of belief, in spite of delegations sent by the Mennonites of Montbéliard, Alsace, and Lorraine, but apparently continued to permit assignment to noncombatant units. Also the Mennonites' objections to the oath were honored, and as early as 1810 the French supreme court (Cour de Cassation) accepted a simple promise as alternative.

Very little is known as yet of Mennonites in the entire period 1712-1870 outside of the principality of Montbéliard, except for the joint project just mentioned of sending a delegation to Napoleon (see Alsace). A few generalizations may nevertheless be hazarded. (1) Parallel to the movement to Montbéliard, a smaller group of Amish from Markirch settled in the south of the Sundgau (present congregations of Birkenhof and Holee). (2) In the latter half of the 18th century a fresh Swiss (non-Amish) settlement was formed in the wooded area of Normanvillars (present congregation of Florimont— see Gratz article, Mennonite Quarterly Review, April 1952). (3) The expulsion from Alsace, ordered in 1712, was never fully carried out. The Count Palatine of Birkenfeld, on whose territory of Ribeaupierre the Ste-Marie-aux-Mines settlement was located, and who had lost 70 families and thereby a third of his income, requested from Louis XV and finally received in 1728 the authorization to tolerate those who remained, on condition that they should not increase in numbers. Those who did remain were frequently annoyed but never driven out. (4) The infiltration into Lorraine from the Vosges but also from the Palatinate continued uneventfully, reaching Nancy by 1850 and Bar-le-Duc and Chaumont by the end of the century. Widely scattered, the Mennonites of Lorraine had great difficulty in maintaining any sort of church life, and held on largely through the force of tradition, family links, and continuing relations with the stronger centers at Montbéliard and in Germany beyond Zweibrücken. Meetings were monthly or even less frequent; congregational leaders were devoted but frequently lacking in vision and occasionally even illiterate. Sermons and prayers were read or repeated by rote (see Pierre Sommer's reminiscences in Almanack Mennonite du Cinquantenaire, 1951). (5) From all these areas migration to America continued intermittently through the entire period from 1820 to 1900, making up the major part of the Amish settlements from western Pennsylvania to Iowa. The increasing difficulty of obtaining assignment with the noncombatant service, and perhaps also a dissatisfaction even with the non-combatant privilege, was one of the continuing reasons for emigration, with the result that by the end of the 19th century there was no longer any objection raised against full military service by Mennonites remaining in France.

The annexation of Alsace and a part of Lorraine by Germany in 1871 cut off both the weak congregations of Lorraine and the strong center of Montbéliard from their brethren in German-speaking territory. The next quarter-century was the transition to the French language in both home and church, but not without difficulties which weakened the hold of traditional religion on the younger generations. In the 1890s young people who knew only French were obliged to memorize in German the 18 articles of the Dordrecht Confession, and to pronounce in German the formula, "My desire is . . . ," whose original intent was to guarantee the principle of baptism on confession of faith, but which could mean no more to them than if it had been in Latin. This language problem, coupled with the wide dispersion of Mennonite families, the end of discrimination against them, the growth of French nationalism and centralism, continuing emigration, and mixed marriages, led to the disappearance of a number of congregations between the Alsatian border and the Moselle (Blanc Rupt, Bitscherland, "Welschland," Dieuze, Morhange, Nancy, Herbeviller, Repaix, Vosges, "Lothringer"; see articles on these congregations). This evolution has continued up to the present, taking in as well most of the congregations of the Vosges (Ste-Marie-aux-Mines, Chatenois, Quelles, Benaville, Salm, Senones, Struth, of which only the reconstituted congregation of the Hang remains). The general spiritual tone of Mennonitism in France and Alsace was at its lowest point toward the end of the 19th century.

Beginning around 1900 several factors combined to initiate a degree of renewal. (1) The Alsatian churches began to hold regular conferences and entered into contact with the Conference of South German Mennonites. After the return of Alsace-Lorraine to France (1918) the Alsatian conference united the German-speaking Mennonites in France (see Association des Eglises and Conference of Mennonites in France). (2) A new immigration of Swiss Mennonites into Upper Alsace brought fresh leadership into the Alsace-Lorraine Conference, and led to the formation of two new (chiefly Swiss) congregations (see Pfastatt and Altkirch). This brought the end of conservatism in matters of dress as well as the observance of feetwashing, although the latter still survived in five French congregations. (3) Outside influences, such as the Salvation Army, and revivalists like Ruben Saillens in France, St. Chrischona, and, later, Pentecostalism in Alsace, brought both renewal of spiritual concern and a certain lack of respect for peculiarly Mennonite traditions. Surprisingly, the Pentecostal influence produced more interest in nonresistance and in a critical attitude toward nationalism than did the types of spirituality more favored by Mennonite leadership. (4) A revitalization of the Mennonite heritage, involving a renewed interest in personal spiritual life, in missions, in Mennonite history, in international Mennonite contacts, and in nonresistance, was undertaken by Pierre Sommer (minister of the Repaix congregation, later at Montbéliard) and Valentin Pelsy of Sarrebourg. Their efforts brought into being the French-language conference beginning in 1906, a ministers' manual, and the supported post of a traveling pastor to visit scattered families. This development expanded further after World War II to bring about the naming of a second traveling pastor (under the German-language conference), and the formation of a mission committee, a youth commission, and a charitable organization (Association Fraternelle Mennonite), all of which served both language groups. Christ Seul began its appearance as a monthly journal in 1907.

The Amish origin of the French Mennonites is now scarcely visible; though only a generation ago there remained a conscious conservatism in matters of dress. Only the congregations of Diesen, Hautearne, Meuse, Birkenhof, and Montbéliard retained the practice of feetwashing. Each congregation was autonomous, choosing its own ministers and elder (or elders—Montbeéiard had four elders in 1954). The conferences had a purely consultative character. The ministers and elders of both conference groups met conjointly semiannually in Valdoie after 1951 for study and discussion, but this meeting had no administrative authority. The Dordrecht Confession was still the official expression of belief and its study (and in some cases memorization) a prerequisite to baptism, though Articles XIV, XVI, and XVII were no longer literally applied. Most congregations met biweekly. Sunday schools (for unbaptized children) were the exception, but their importance was rapidly growing in the 1950s. Children of Mennonite families were generally baptized by aspersion at 14-15 years; adhesion of members of non-Mennonite ancestry was rare.

Mennonite Central Committee work in France began in February 1940 as an extension of the work in Spain, and continued under the direction of Ernest Bennett, J. N. Byler, and Henry Buller until 26 January 1943 when the remaining workers, Lois Gunden and Henry Buller, were interned by the Germans. The work was first of all directed toward Spanish refugees at Cerbere on the Spanish border, and grew also to include child-feeding programs, such as the one at Lyons. The child work was carried on through the war during the absence of Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) workers by Augustin Coma, a Spanish refugee, and Roger Georges, a French citizen, partly with funds left by MCC and partly with subsidies from French government welfare agencies. Work was again begun in early 1945, both with children's homes and with more general food and clothing distributions. By the end of the year 14 MCC workers were directing at least seven children's homes besides the clothing distribution. In 1946 contact was for the first time established with the French Mennonites, and late in the same year a reconstruction unit was established in Wissembourg, Alsace. Increasing contacts with French Mennonites led to the formation of a Youth Commission in the French churches (1948), the beginning of summer Bible camps (1949), the foundation of the Association Fraternelle Mennonite (1950), and the purchase of two properties for the continuation of the MCC's children's work in collaboration with the French at Valdoie near Belfort and at Mont des Oiseaux near Wissembourg. The Mennonite Church began a mission in Paris in 1953.

Congregations existing in France in the early 1950s were Altkirch, Belfort, Birkenhof, Colmar, Diesen, Florimont, Geisberg, Le Hang, Haute-Marne, Luneville-Baccarat, Meuse, Montbéliard, Neuf-Brisach, Pfastatt, Pulversheim, Sarrebourg, and Toul. (See articles on all these congregations as well as the extinct ones listed earlier.) A monthly meeting began in Paris in 1954, but at that time was without congregational organization. Mennonites in France were mostly engaged in agricultural pursuits, although a movement toward all levels of urban employment had been marked in the preceding half-century.

2010 Update

Between 2000 and 2009 the following Anabaptist group was active in France:

| Denominations | Congregations in 2000 | Membership in 2000 | Congregations in 2003 | Membership in 2003 | Congregations in 2006 | Membership in 2006 | Congregations in 2009 | Membership in 2009 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Association des Églises Évangéliques Mennonites de France | 30 | 2,046 | 30 | 2,050 | 32 | 2,100 | 32 | 2,100 |

See Farming and Business. For more detailed local history see the provincial articles Alsace and Lorraine

Bibliography

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. I, 681-85.

Mathiot, Ch. Recherches historiques sur les Anabaptistes de l' ancienne Principaute de Montbeliard, d' Alsace et des regions voisines. Belfort, 1922.

Mennonite World Conference. "2000 Europe Mennonite & Brethren in Christ Churches." Web. 27 February 2011. http://www.mwc-cmm.org/Directory/2000europe.html.

Mennonite World Conference. "2003 Europe Mennonite & Brethren in Christ Churches." Web. 27 February 2011. http://www.mwc-cmm.org/Directory/2003europe.html.

Mennonite World Conference. "Europe." Web. 27 February 2011. http://www.mwc-cmm.org/Directory/2006europe.pdf.

Mennonite World Conference. "World Directory: Europe." Web. 13 June 2010. http://www.mwc-cmm.org/en15/files/Members2009/EuropeSummary.doc.

Michiels, Alfred. Les Anabaptistes des Vosges. Paris, 1860.

Pelsy, V. and P. Sommer. Précis d'Histoire des Eglises Mennonites. Montbeliard, 1914 and reprint 1937.

Les Soirees Helvetiennes, Alsaciennes, et Fran-Comtoises. Amsterdam and Paris, 1772.

| Author(s) | John Howard Yoder |

|---|---|

| Date Published | February 2011 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Yoder, John Howard. "France." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. February 2011. Web. 2 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=France&oldid=121959.

APA style

Yoder, John Howard. (February 2011). France. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 2 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=France&oldid=121959.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, pp. 359-362. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.