Difference between revisions of "Fraktur (Illuminated Drawing)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m (Text replace - "</em><em>" to "") |

m (Text replace - "<em>Mennonite Quarterly Review</em>" to "''Mennonite Quarterly Review''") |

||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

Froese, Leonhard. "Das Pädagogische Kultursystem der Mennonitischen Siedlunsgruppe in Russland." Diss., U. of Göttingen, 1949: 9-66. | Froese, Leonhard. "Das Pädagogische Kultursystem der Mennonitischen Siedlunsgruppe in Russland." Diss., U. of Göttingen, 1949: 9-66. | ||

| − | Hershey, Mary Jane Lederach and others. "Andreas Kolb, 1749-1811." | + | Hershey, Mary Jane Lederach and others. "Andreas Kolb, 1749-1811." ''Mennonite Quarterly Review'' 61 (1987): 121-201. |

Isaac, Franz. <em>Die Molotschnaer Mennoniten.</em> Halbstadt, Taurien: H. J. Braun, 1908: 274-275. | Isaac, Franz. <em>Die Molotschnaer Mennoniten.</em> Halbstadt, Taurien: H. J. Braun, 1908: 274-275. | ||

Revision as of 23:05, 15 January 2017

1956 Article

Illuminated Manuscripts among Russian Mennonites

The art of penmanship and the production of illuminated writings dates back to the Middle Ages. Particularly the initial letters in printing and writing were ornamental, sometimes using many colors. This was also known as Kanzleischrift, practiced in the offices of the royal courts, which was taken over by schools and survived, in some forms, until the 19th century. Among the Mennonites, the Hutterites practiced this art of penmanship in the writing of their chronicles, but the Pennsylvania-German Mennonites and the Prusso-German Mennonites have also used this art.

H. Görz reported that after the hardship of the pioneer days had been overcome, the elementary schools among the Mennonites of the Ukraine strongly emphasized this art of penmanship (Frakturen). Recognition cards were produced by the teacher and the older gifted pupils and distributed among the best pupils of the school. Particularly for Christmas and New Year's Eve they produced the traditional Weihnachtswunsch and Neujahrswunsch, which carried an appropriate poem pertaining to Christmas or New Year's Eve, which the children presented to their parents on the morning of these holidays, reciting the poetry before they received their presents. The art of penmanship and the production of illuminated manuscripts filled a considerable part of the curriculum of elementary training in Mennonite schools in Russia during the first half of the 19th century. When, through Cornies' effort, the educational level was raised, this art was discouraged as a waste of time, but it somehow survived and was practiced in some form until the Mennonite communities in Russia disintegrated under the Soviets. Some of the teachers belonging to the "old school," such as J. D. Rempel (in Germany in the 1950s), hardly ever wrote a letter which did not have a beautifully illuminated salutation. The practice of producing illuminated wall mottoes could still be found among the Mennonites of South America in the 1950s. Some of the teachers developed into artists in their own right (H. J. Janzen, Joh. H. Janzen, J. P. Klassen, and others). Numerous copies of illuminated manuscripts and Christmas and New Year's greetings have been preserved in Mennonite homes of the prairie states and provinces, and gradually reached the Mennonite Library and Archives at Bethel College, which in the 1950s possessed a collection of them, some of which were produced in the beginning of the 19th century. -- Cornelius Krahn

Illuminated Manuscripts among the Pennsylvania Mennonites

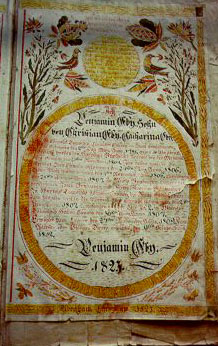

The art of fraktur or illuminative writing, as it was practiced by the Pennsylvania Germans in colonial times and down to 1840-1850, by which manuscript specimens were written in ornamental capital letters decorated in several colors, was clearly a descendant of the medieval art of manuscript illumination, but came possibly also directly from similar practices in the schools of Middle and South Germany from which the colonial immigrants to Pennsylvania came. It was a form of religious art, almost never applied to secular themes, usually including either Scripture verses or expressions of piety. The block letters were ornamented, and the entire drawing was often ornamented with illuminative borders, overhanging tulips or lotus flowers, birds, angels blowing trumpets, etc. In America it was chiefly perpetuated by deliberate instruction in German private schools by German schoolmasters, and the coming of the public schools in 1840-1850 meant its end.

Among the types of fraktur work to be noted were the illuminated manuscript songbooks of the Ephrata Cloister of the mid-18th century, small plain manuscript songbooks made in Mennonite schools in the early 19th century with illuminated title pages giving the owner's name and the writer's school, illuminated ownership pages to printed songbooks, rewards of merit, copyforms made for pupils in Mennonite schools, bookmarks, baptismal certificates for Lutherans and Reformed, marriage and death registers in Bibles.

The chief geographical area of the practice of fraktur was in central Bucks County; specimens of the art from certain neighboring counties have also been preserved, especially Lehigh. Although Mennonites apparently were among the leaders in the art, they were not the only practitioners. However, the last surviving masters were two Mennonites, Jacob Gross of New Britain, and John H. Detweiler of Perkasie, Bucks County, noted by Mercer (Survival, 432) as still alive at an advanced age in 1897. John D. Souder (1867-1944), a Mennonite of Telford, Bucks County, revived the art in his late years and is said to have produced nearly 1,000 specimens of fraktur, largely mottoes and anniversary certificates for his friends, though not of the quality of older specimens. Bucks County Mennonite emigrants carried the art of fraktur with them to their settlement near Vineland, Lincoln County, Ontario (ca. 1800), where a number of specimens have been preserved.

One of the noted early fraktur artists was Christopher Dock (d. 1771), the "pious schoolmaster of the Skippack," who had some 25 of his illuminated texts posted on the walls of his school. Abraham H. Cassel of Harleysville, Pa., whose father was a pupil in Dock's school, had a collection of Dock's illuminated texts, which he gave to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. The Goshen College Library in the 1950s had a collection of some 30 pieces of fraktur including five small manuscript Mennonite songbooks. Goshen's oldest piece was an illuminated text copyform made in the Deep Run Mennonite school in Bucks County in 1783.

In recent times fraktur art has been rediscovered as a part of the rediscovery of Pennsylvania-German folk art, and good specimens have become museum items. The most successful collector was Henry S. Borneman (d. 1953), who published Pennsylvania German Illuminated Manuscripts, A Classification of Fraktur-Schriften and an Inquiry into their History and Art (Pennsylvania German Society, Norristown, 1937) with splendid four-color reproductions of 32 specimens. Borneman listed the names of 107 fraktur artists whose work has survived. His Pennsylvania German Book Plates (Philadelphia, 1953) has 24 four-color reproductions. -- Harold S. Bender

1989 Update

Dutch-Prussian-Russian

Fraktur, the art of beautiful penmanship and illuminated drawings on paper, flourished from 1760-1860 as a teaching tool in Mennonite Prussian and Russian schools. Teachers would also produce Fraktur to decorate house blessings and to inscribe title pages of books.

Most examples were written in German and can be grouped as: Vorschriften (copybooks), Weihnachts and Neujahrswünsche (Christmas and New Year's greetings), Bücherzeichen (bookplates), Rechenbücher (arithmetic books), Belohnungen (certificates of award), Bilder (drawings), Haussegen (house blessings), Irrgarten (labyrinths), and Scherenschnitte (scissor or knife cuttings). The Vorschrift was used to teach children the alphabet; it was written in their best penmanship. The texts with illuminated letters and drawings were studies in Bible, nature, and geography. Weihnachts- und Neujahrswünsche were created by children as gifts to their parents. These reflected joys and hardships that the Mennonite people experienced. Bücherzeichen identified ownership of Bibles, catechism books, and hymn-books, and would often include genealogical information. Among the illuminated books, Rechenbucher were the most common. These books included many handwritten pages of arithmetic problems, colorful designs, and illustrations. For excellent work and conduct, children were given a Belohnung (reward) drawing executed by the teacher. Texts for Irrgarten were penned in a verbal maze as a religious admonition, game, or love note. Delicately cut Scherenschnitte included narration and colorful symbols similar to Irrgarten. Roses were the most common flower design; animals, angels, geometric patterns, and architectural settings were also used.

Rag paper and quills made from goose and turkey feathers were used prior to 1860. Pigments produced for water color drawings were derived from plants and trees.

Reference to Vorschriften first appear in a Dutch manuscript for the Mennonite church school in Altona, Germany; a later copy was translated into German about 1750. Some of the early Prussian educators adept in Frakturmalen (malen = painting, i.e., drawing) were Dirck Bergman (1789), Bernard Rempel (1831), and Peter Penner (1838). Fraktur instruction is noted in Russian Mennonite school manuals by Tobias Voth (1820), Jakob Braül (1830), and Heinrich Heese (1842). Many children and teachers continued Frakturmalen in later years. After 1870 some Fraktur works were written in Russian. -- Ethel Ewert Abrahams

Swiss-Pennsylvania-German

Among German-speaking immigrants bringing the practice of "Fraktur-Schriften" to Pennsylvania were Mennonites with roots in Switzerland and southern Germany. Christopher Dock, a Colonial Mennonite schoolmaster who taught at Germantown, Skippack, and Salford, describes in his Schul-ordnung (1750) his way of encouraging his students by rewarding them with small drawings of a flower or a bird. At other times the reward might be a certificate (Zeugniss) or a writing-sample (Vorschrift). The earliest known examples of Pennsylvania Fraktur are attributed to Dock.

A number of students who were taught by Dock in the Salford and Skippack meetinghouses later became schoolmasters in this intensely Mennonite area. The result was an extensive local flowering of folk art in Fraktur form. Two of Dock's students were Huppert Cassel (b. 1751), who taught at Salford and Skippack, and Andreas Kolb (1749-1811), who taught at Salford and Saucon. Both became prolific and skilled artists in Fraktur.

Contemporary with these teachers was the Lutheran, Herman M. Ache (d. 1815), a resident of lower Salford. Of notable influence as a Fraktur-artist, he taught Mennonite children sporadically from 1756 to the 1770s at Franconia, Salford, and Skippack.

This tradition continued into the mid-19th century in the Franconia Mennonite Conference, skillfully practiced by schoolmasters such as the following: Jacob Gottschall (1769-1845), a bishop at Franconia after 1813, who had been taught in a Bucks County Mennonite school by Lutheran Fraktur artist, Johan Adam Eyer (1755-1837); Jacob Hummel (d. 1822), a Mennonite who taught at Lower Salford and Limerick; Durs Rudy, a Lutheran who taught Mennonite children at Skippack 1804-06; Isaac Z. Hunsicker (1803-70) of Skippack, a Mennonite teacher and itinerant Fraktur-writer whose work includes a reward for Susan Alderfer at Salford in 1831 and who soon thereafter moved to Canada where he continued his art; Henry Johnson (1806-79), a Mennonite teacher for decades at the Skippack school; and the three sons of Bishop Jacob and Barbara (Kindig) Gottschall, Martin K. (1797-1870), William K. (1801-76), and Samuel K. (1808-98), whose colorful and imaginative work grandly culminated a century of Fraktur-production in the Franconia-Salford-Skippack Mennonite community.

In addition of Isaac Z. Hunsicker, major fraktur artists in Ontario included Samuel Moyer (1767-1844); Christian L. Hoover (1835-1918); Abraham Latschaw (1799-1870); Joseph Bauman (1815-1889) and Anna Weber (1814-1888).

Mennonite Fraktur was almost completely school related. The Vorschriften (writing samples) were used to teach the children penmanship and design, the Scriptures, hymns, and other spiritual truths. Other forms include small rewards, bookplates in manuscript singing school books and hymn books, and larger, illustrative "teaching pieces" used in the classroom to teach the alphabet and spiritual understandings. -- Mary Jane Lederach Hershey

Appreciation for the aesthetic, moral, devotional, genealogical, and sentimental values associated with Fraktur art has increased markedly in recent decades in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia as is evident from the development of personal and church-related collections, from occasional courses devoted to the subject, and from a minimal revival of the art, most notably among Mennonites in Bucks and Montgomery Counties, Pennsylvania.

In Lancaster County and surrounding areas, the Lancaster Mennonite Conference Board of Congregational Resources sponsors occasional adult education courses on Fraktur and on calligraphic styles derived from Fraktur, but they are usually taught by non-Mennonite practitioners. At the People's Place Museum, Intercourse, Pa., Michael S. L. Kriebel, an Old Order River Brethren artist, was devoting the majority of his time to Fraktur art in the late 1980s. Few Mennonites in central and western Pennsylvania, Maryland, or Virginia have achieved distinction as serious practitioners of Fraktur art.

Institutions that have collected Mennonite-related Fraktur of the eastern United States in the 1980s include the following in Pennsylvania: Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society, Lancaster; Muddy Creek Farm Library, Ephrata; People's Place, Intercourse; Juniata District Mennonite Historical Society, Richfield; Germantown Mennonite Historical Library, Philadelphia; Mifflin County Mennonite Historical Society, Belleville; the Pequea Bruderschaft Library, Gordonville; Allegheny Conference Archives, Johnstown; and the Mennonite Historical Association of the Cumberland Valley, State Line. In Grantsville, Maryland, is the Casselman River Area Amish and Mennonite Historians group, and in Ontario, Conrad Grebel University College, Waterloo, Ontario, and the Heritage Historical Library, Aylmer. Earlier established centers with Fraktur collections, include the Mennonite Historical Library, Goshen College, Goshen, Indiana; Eastern Mennonite University, Harrisonburg, Virginia; Messiah College, Grantham, Pennsylvania; and the Mennonite Historical Library of Eastern Pennsylvania, Lansdale, Pennsylvania. -- Carolyn C. Wenger

Bibliography

Abrahams, Ethel Ewert. "Anna's Wünsche." Mennonite Life 34, no. 2 (June 1979): 21-25.

Abrahams, Ethel Ewert. "Fraktur by Germans from Russia." American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, Work Paper 21 (Fall 1976): 12-16.

Abrahams, Ethel Ewert. Frakturmalen und Schönschreiben. North Newton, KS: Mennonite Press, 1980.

Abrahms, Ethel Ewert. "The Art of Fraktur-Schriften among the Dutch-German Mennonites." M.A. thesis, Wichita State U., 1975.

Bird, Michael S. Ontario Fraktur: a Pennsylvania-German Folk Tradition in Early Canada. Toronto: M.F. Feheley Pub., 1977.

Bornemen,; Henry S. Pennsylvania German Bookplates, Publications of Pennsylvania German Society, 54. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania German Society, 1953.

Bornemen, Henry S. Pennsylvania German Illuminated Manuscripts, rev. ed. New York: Dover Publications, 1973.

Brumbaugh, M. G. The Life and Works of Christopher Dock. Philadelphia, 1908.

Dock, Christopher. Schulordnung. Columbiana, Ohio: Jacob Nold, 1861.

Duerksen, Cornelius. "Regeln der Recht schreibung fur Kleinkinderschulen, 1851," and "Bechtschreibunglehre, 1878," Alexanderthal village, South Russia, handwritten in German, Raymond F. Wiebe collection (Hillsboro, Kansas, USA)

"Entwürfe und Aufzeichnungen über die Mennonitenschule in Altona-Hamburg." N.d., possibly 1700-1750, handwritten in German, Mennonite Library and Archives (North Newton, Kansas, USA).

Epp, D. H. Die Chortitzer Mennoniten. Odessa: A. Schultze, 1899: 122-124.

Görz, H. Die Molotschnaer Ansiedlung. Steinbach, MB, 1950: 92.

Good, E. Reginald. "Isaac Ziegler Hunsicker: Ontario schoolmaster and Fraktur artist." Pennsylvania Folklife 26, no. 4 (1977).

Good, E. Reginald. Anna's Art : the Fraktur Art of Anna Weber, a Waterloo County Mennonite Artist, 1814-1888. Kitchener, ON: Pochuana Publications, 1976.

Friesen, Peter M. Alt-Evangelische Mennonitische Brüderschaft in Rußland (1789-1910). Halbstadt: Raduga Verlag, 1911: 633.

Friesen, Peter M. The Mennonite Brotherhood in Russia (1789-1910), trans. J.B. Toews, et al. Fresno, CA. : Board of Christian Literature, 1980: 780.

Froese, Leonhard. "Das Pädagogische Kultursystem der Mennonitischen Siedlunsgruppe in Russland." Diss., U. of Göttingen, 1949: 9-66.

Hershey, Mary Jane Lederach and others. "Andreas Kolb, 1749-1811." Mennonite Quarterly Review 61 (1987): 121-201.

Isaac, Franz. Die Molotschnaer Mennoniten. Halbstadt, Taurien: H. J. Braun, 1908: 274-275.

Lichten, Frances. Folk Art Motifs of Pennsylvania. N.Y., 1954.

Lichten, Frances. "Fractur from the Hostetter Collection." The Dutchman 6 (1954).

Mercer, H. C. The Survival of the Medieval Art of Illuminative Writing Among Pennsylvania Germans. Reprint from Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 36 (1898): No. 156, 423-432.

Neufeld, A. Die Chortizer Centralschule, 1842-1892. Berdjansk: Druck von H. Ediger, 1893: 15.

"Ontwerp am een Gemeenteluijke School in Altona" (n.d., possibly 1650-1700), handwritten in Dutch, Mennonite Library and Archives (North Newton, Kansas, USA).

Riccardi, S. J. "Pennsylvania Dutch Folk Art and Architecture, A Selective Annotated Bibliography." Bulletin of the New York Public Library 46 (1942): 471-483.

Robacker, E. F. "Major and Minor in Fraktur." The Dutchman 7 (1956): 2-7.

Shelly, Donald A. The Fraktur Writings or Illuminated Manuscripts of the Pennsylvania-Germans. Allentown, Pa.: The Pennsylvania-German Folklore Society, 1958-59.

Stoudt, J. J. Consider the Lilies How They Grow. Pennsylvania German Folklore Society, II, 1937.

Stoudt, J. J. Pennsylvania Folk Art. Allentown, PA, 1948.

Studer, Gerald C. Christopher Dock, Colonial Schoolmaster. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1967.

Weiser, Frederick S. and Howell J. Heaney, comps., The Pennsylvania German Fraktur of the Free Library of Philadelphia, 2 vols. Breinigsville, Pa.: The Pennsylvania German Society, 1976.

Weiser, Frederick S. "IAE SD: the Story of Johann Adam Eyer (1755-1837), Schoolmaster and Fraktur Artist With a Translation of His Roster Book, 1779-1787," in Ebbes fer Alle-Ebber, Ebbes fer Dich (Something for Everyone, Something for You), ed. Albert F. Buffington and others. Breinigsville, Pa.: The Pennsylvania German Society, 1980.

Additional Information

Ervin Beck's Bibliography on Mennonite and Amish Folklore and Folk arts.

| Author(s) | Cornelius Krahn |

|---|---|

| Harold S. Bender | |

| Ethel Ewert Abrahams | |

| Mary Jane Lederach Hershey | |

| Carolyn C. Wenger | |

| Date Published | 1989 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Krahn, Cornelius, Harold S. Bender, Ethel Ewert Abrahams, Mary Jane Lederach Hershey and Carolyn C. Wenger. "Fraktur (Illuminated Drawing)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1989. Web. 1 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Fraktur_(Illuminated_Drawing)&oldid=143565.

APA style

Krahn, Cornelius, Harold S. Bender, Ethel Ewert Abrahams, Mary Jane Lederach Hershey and Carolyn C. Wenger. (1989). Fraktur (Illuminated Drawing). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 1 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Fraktur_(Illuminated_Drawing)&oldid=143565.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, pp. 10-12; vol. 5, pp. 308-310. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.