Difference between revisions of "Dress"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

SamSteiner (talk | contribs) (added links) |

m (Text replace - "<em class="gameo_bibliography">Mennonite Quarterly Review</em>" to "''Mennonite Quarterly Review''") |

||

| Line 122: | Line 122: | ||

The past generation of dress transition in the Mennonite (MC) and Brethren in Christ churches merits further study, particularly focusing on the following issues: (1) for groups with dress requirements comparison of rules for men and women; (2) women's perceptions on dress issues; (3) case studies in shifting dress patterns in particular congregations and church districts--including the role of open candid discussion and silent behavioral change; (4) case studies of individuals experiencing changing restrictions in dress; (5) comparative dress restrictions in other groups, e.g., Free Methodists, <em>Aussiedler</em> (emigrants) from Russia. -- <em>Robert S. Kreider</em> | The past generation of dress transition in the Mennonite (MC) and Brethren in Christ churches merits further study, particularly focusing on the following issues: (1) for groups with dress requirements comparison of rules for men and women; (2) women's perceptions on dress issues; (3) case studies in shifting dress patterns in particular congregations and church districts--including the role of open candid discussion and silent behavioral change; (4) case studies of individuals experiencing changing restrictions in dress; (5) comparative dress restrictions in other groups, e.g., Free Methodists, <em>Aussiedler</em> (emigrants) from Russia. -- <em>Robert S. Kreider</em> | ||

= Bibliography = | = Bibliography = | ||

| − | Baehr, Karl. "Secularization Among the Mennonites of Elkhart County, Indiana." | + | Baehr, Karl. "Secularization Among the Mennonites of Elkhart County, Indiana." ''Mennonite Quarterly Review'' 16 (July 1942): 131-60. |

Bossert, G., Sr. and G. Bossert, Jr. <em class="gameo_bibliography">Herzogtum Württemberg. </em>Leipzig, 1930: 691, 741, 806, 881. | Bossert, G., Sr. and G. Bossert, Jr. <em class="gameo_bibliography">Herzogtum Württemberg. </em>Leipzig, 1930: 691, 741, 806, 881. | ||

Revision as of 22:59, 15 January 2017

[This is a combination of J. C. Wenger's comprehensive essay from the mid-1950s and Robert Kreider's 1989 update. Both articles focus primarily on Mennonites in the United States, though they describe a number of Mennonite groups in Ontario, and small Mennonite groups located elsewhere in Canada.]

1956 Article

Introduction

Distinctive religious costumes have been worn by custom or by requirement by many and varied groups in Christian history; for example, by religious and monastic orders (monks and nuns), clergy of various ranks, and Salvation Army workers. Special garments have been prescribed for certain important religious occasions such as baptism, confirmation, weddings, and funerals. However, none of these has been directly based on the Scriptures and none has had any bearing or influence on Mennonite distinctive costume or dress regulations.

It is difficult at times to determine, either in Europe or America, whether what seems to have been (and may still be) a distinctive Mennonite item of costume is the result of deliberate choice on religious grounds established and maintained by action of the church, or is purely a sociological phenomenon such as the retention of older forms of costume because of resistance to change. Much of the peculiarly Mennonite costume and clothing regulation is probably of the latter character. For most Mennonites, with the exception of Holland and the North German city congregations, have been rural, and rural people have been notorious for their resistance to change, particularly in earlier times before modern urban culture penetrated rural areas, as well as in current pockets of cultural isolation. Religious sanctions have, of course, often been imposed to maintain earlier costume forms, and at times even Biblical sanctions by specific verses have been claimed, sometimes with a faulty exegesis or application of quite irrelevant passages (e.g., "boots" from the German of Ephesians 6:15, "an den Beinen gestiefelt," or the beard requirement from Leviticus 19:27, "[not] mar the corners of thy beard," etc.). Actually, the customs or traditions originated first, to be reinforced later by church sanctions. In the most conservative American groups (Old Order Amish|Amish]] and Old Colony Mennonites) most of the clothing regulations have never been written out or specified. The power of custom suffices.

On the other hand, the doctrine of separation from the world, and the strong sense of the actual separation of the small group from the larger general society has worked powerfully (1) to produce distinctive non-worldly costume, and (2) to restrain the group from following the changes of costume and fashion in "the world" about them. This, reinforced by the instinctive spirit of withdrawal, humility, and even inferiority resulting from persecution, besides a very real poverty in many cases, and a strong teaching against pride and for simplicity, has often furnished deep religious motivation for distinctive (though not necessarily uniform) costume. Distinctive and plain garb has been characteristic of many earnest Christian groups past and present, not only of Mennonites, and many such have resisted the changing fashions of the society in which they lived, which fashions were often not only extreme or unhealthful, but also immodest or expensive. Designers and manufacturers of fashionable costume have themselves stated that fashions are deliberately changed to increase sales, and have even been designed to emphasize sex.

The strongly patriarchal character of the more conservative Mennonite groups may also contribute to the emphasis upon controlled costume. The elders and ministers may have such a strong sense of domination as shepherds over their flocks that they consciously or unconsciously seek for outward signs of submission which are most readily furnished by uniform, conservative, distinctive items of costume and drab and dark colors. The emphasis upon submission as one of the chief virtues desired in members may well be an index to the psychology of costume in such a patriarchal or near-patriarchal type of church life.

Another principle affecting some Mennonite costume has been that of sex distinction in attire. (Deuteronomy 22:5, "The woman shall not wear that which pertaineth unto a man, neither shall a man put on a woman's garment.") Although society in general has observed sex distinction in clothing, yet Mennonites have often been more conservative than the rest of society on this point, particularly in recent times when many women are wearing slacks or shorts.

In America plainness of attire was long characteristic of numerous "sects" in Eastern Pennsylvania and adjacent areas, who were often grouped together as "the plain people." This category, which once included Quakers, Moravians, Schwenckfelders, and Brethren or Dunkards as well, now includes only Mennonites, Amish, and Brethren in Christ (formerly called River Brethren or Tunkards in Canada).

It seems probable that the Quaker costume imported from England in the 17th century, when the Quakers were the governing class in Pennsylvania, and when they were a nonresistant, strict-living, nonworldly group, had considerable influence on the costume of the other "plain sects," who were all of German origin, and were all both nonresistant and strict-living. The later gradual but complete loss of plain attire by some of the "plain" people, and dilution in the practice by others, may be due in part to a loss of the sense of "separation from the world" accompanying cultural and religious assimilation. Sometimes the process of accommodation to prevailing styles was aided by the introduction of cheap factory-made clothing and the loss of the practice of weaving and clothing construction at home. On the other hand, the concomitant loss of distinctive doctrines such as nonresistance along with the loss of distinctive costume (nonconformity in dress) may point to spiritual decline or change as a significant factor in the change of costume.

Every item of men's and women's clothing has been involved at some time in Mennonite history, or in some Mennonite group, in the matter of a distinctive Mennonite costume, either as prohibited or prescribed in one form or pattern or another. A mere enumeration results in an enormous list. For most of these, special articles will eventually be found in this Encyclopedia. Only a few summary notes can be given here. Some of the costume prescriptions have been purely traditional or customary and unwritten, while others have been put into specific rules by congregations or conferences. Disciplinary action has usually followed violation of the regulations, whether written or not. On the other hand, slow changes have usually modified the traditional practices or rules without direct action.

The following is a summary list of costume traditions or regulations which have been applied at one time or another in history in one or another Mennonite group or area. This list is probably not exhaustive and refers primarily to practices among the most conservative North American groups such as Old Order Amish and Old Colony groups, but also in part to the large Mennonite Church (MC) group and related groups, as well as to the more conservative Russian Mennonite groups in Canada and Mexico. Details of costume prescriptions among the earlier European Mennonites, particularly in Holland and Switzerland, have not been available. Headdress: for women, kerchiefs or bonnets have been required, and hats forbidden or a specific type of broad beaver or straw hat required; for men requirements have been black hats, broad brim, without crease in crown, or with a flat crown, or caps instead of hats. Hairdressing: for women, bobbed hair has been forbidden, a center part required; for men, short cut hair has been forbidden. Overcoats: for women coats have been taboo in favor of shawls, or only half-length coats allowed; for men, long overcoats with capes have been required. Pants: for men knee breeches or broadfall type (sailor type) have been required. Dresses: a prescribed cut (cape dress) has been required, and Configured cloth of solid color with full-length sleeves, and the dress quite long. Aprons have been required for women, or for wives of ministers alone. Coats for men: collarless, divided tail or frock coat have been required. Fasteners: for men and women buttons have been forbidden, hooks and eyes required for men, pins for women. Corsets have been forbidden. Stockings for women: silk forbidden, black color required, anklets forbidden. Neckties for men forbidden, or required to be bow ties instead of four-in-hand. Suspenders for men have been forbidden in whole or in part. Shoes: buckle, lace, and button shoes have been required or forbidden, boots required for preachers. Shrouds: white has been required. Wedding dress: floor length and white color have been forbidden. Color: bright or light colors have been forbidden for all items of costume from hats to shoes, both men and women, and black or gray required. Clothing material: silk has been forbidden, and home-woven cloth required. Homemade clothes have been required rather than "store" clothes.

Interestingly often the minister (and his wife) has been required (by custom or regulation) to be more conservative than the group as a whole, as a result of which, unintentionally, a distinctive clerical garb has developed in a brotherhood which has strictly opposed clericalism. Sometimes this has meant for the minister a long black frock coat, in. other cases a clerical coat much like the state church Protestant or Roman Catholic attire. Sometimes (in Europe, in Holland and North Germany) ministers and members of church boards are required to wear high hats and frock coats to church services. Sometimes boots have been required. Among certain conservative Manitoba groups the preacher is even required to continue to wear the coat he was ordained in.

Wedding costumes have often been fixed. Among the most conservative Manitoba groups brides must wear black. In some groups the floor-length wedding gown is forbidden. In some groups (e.g., Franconia Conference of the Mennonite Church) the dead must still be buried in white shrouds, while black mourning garments are forbidden.

In the Old Testament only priests were required to wear a religious costume, although Jewish men were required to wear garments with a fringe or tassel of blue as a reminder that they belonged to the Lord (Numbers 15:37-40). The New Testament does not prescribe any form of garb or external dress symbol for Christians. But it gives a number of warnings against external adornment such as worldly styles of hairdressing, and the wearing of gold, pearls, and costly clothing (I Timothy 2:9, 10; I Peter 3:3, 4), and it indicates that Christian women are not to shear off their hair which was given them by God for a "covering" (I Corinthians 11:6, 15). It gives a few hints as to how not to dress, and warns about undue concern for providing food and clothing (in Matthew 5 a situation of poverty).

Anabaptist Costume

Many, though not all, of the early Anabaptists were drawn from the common people and evidently continued to wear the conventional clothing of the common people. There is no evidence to show that the early Anabaptists created any uniform garb for the members of the church. Neither the ministers nor the laity wore any distinguishable attire, as numerous incidents in the Martyrs' Mirror indicate. The Concept of Cologne of 1591 states that it is impossible to prescribe for each individual what he shall wear, but requires simplicity of attire. The Anabaptists took seriously the principle of simplicity of life and the avoidance of the ostentation, display, and luxury of the rich. Menno Simons made a vigorous protest against conformity to the world in attire (Complete Works 1, 144), but did not demand a special garb for the faithful.

In the course of time the Anabaptists became recognizable at sight by their refusal to carry any kind of arms, and by their plainness of dress: no jewellery, lace, etc., were worn. This plainness tended to develop into a sort of standard garb. For as new modes of dress appeared the Anabaptists clung to the older forms, sometimes adapting them over the years, and refusing to keep up with the ever-changing styles which T. J. van Braght likened to the changes of the phases of the moon (Martyrs Mirror E 10). Consequently the Anabaptists early began to make some specific regulations on clothing. For instance, the Strasbourg Discipline of 1568 included the following: "Tailors and seamstresses shall hold to the plain and simple style and shall make nothing at all for pride's sake. Brethren and sisters shall stay by the present form of our regulation concerning apparel and make nothing for pride's sake". This confirms the testimony of Johannes Kessler concerning the Swiss Brethren in 1525: "They shun costly clothing, and despise expensive food and drink, clothe themselves with coarse cloth, (and) cover their heads with broad felt hats. Their entire manner of life is completely humble. They bear no weapon, neither sword nor dagger, but only a short breadknife . . ." (Sabbata, 147 is). Sebastian Franck, perhaps in irony, wrote that the Anabaptists had a ruling on how many pleats the apron must have. By 1600 there were instances in South Germany of Anabaptists being recognized by their clothing (Bossert . . . Wurttemberg I, 691, 741, 806, 881). But the Swiss and South German Mennonites never seem to have developed any specific religious garb; they remained simple Christians avoiding the luxury and ostentation of the rich. When Jakob Amman attempted to introduce avoidance and stricter clothing regulations into the church, he caused the division of 1693, after which his followers (the Amish) practiced extensive regulation of attire, maintaining until the present, in America, specific rules about headdress, hooks and eyes (instead of buttons), cut and color for coats and dresses, homemade instead of factory-made clothing, etc.

European Mennonite Costume

The Dutch Mennonites, even more than the Swiss, did not adopt a special religious garb. When Dutch believers were apprehended it was not by means of identifiable peculiar clothing. As early as 1550 a Dutch Mennonite martyr told the bystanders at his execution that if he could name 20 fellow believers in the surrounding crowd, he would not do so: this would indicate that they wore no specific garb. In 1572 a brother pressed his way through a crowd to encourage a man who was to be martyred, and then merged again with the crowd before the authorities could seize him: this again points to the fact that the Mennonites of Holland at that time wore no distinctive garb. This was even true of the preachers, for in 1565 a minister and part of his congregation were caught by the authorities: the officers could not tell which one was the minister, so the latter voluntarily stepped forward and confessed his identity (these illustrations are taken from van Braght's Martyrs' Mirror; documentation in Wenger, Attire, 22).

By the late 17th century Heinrich Ludolf Bentheim could still say of the Dutch Mennonites: "Above all, they insist on modesty in respect to clothing" (Horsch, Mennonites, 251), though he also states that some of the Amsterdam Mennonites were beginning to wear wigs and other worldly articles. That there was some clothing regulation among the Dutch Mennonites in the 18th century is evident from the testimony of S. F. Rues, who visited the Netherlands specifically to study the Mennonites there, and whose Aufrichtige Nachrichten (Sincere Reports) about them was published in 1743. Rues divided the Dutch Mennonites of that day into two general classes-the stricter groups, which he called "Fine," and the more lenient and tolerant groups, which he called "Coarse." The former prescribed the cut of men's coats and women's dresses, required that clothing be black, prohibited the use of shoelaces or buttons, and required the men to wear beards. On the whole, the stricter rules were followed more closely by the country congregations than in the cities (see summary in Smith, 211-15). Rues also reports (48) a bishop pushing back the cap on the head of a woman candidate for baptism.

In the course of time, such dress regulations were discontinued by the Dutch Mennonites, although the Balk congregation retained some of them until the middle of the 19th century (Mennonitisches Lexikon I, 113). Although the rural congregations generally dress more plainly and simply than do those of urban character, no prescribed garb remains among any European Mennonites.

The history of the costume requirements and traditions in Northwest Germany (Emden, Hamburg), Danzig, and West and East Prussia, was much like that of Holland, since these groups had not only largely Dutch antecedents but also continuing cultural and religious ties with the Dutch Mennonites. The Mennonites who emigrated from the Danzig area to South Russia in turn continued the traditions of their homeland. As rural people the latter remained quite conservative in their costume, and retained much of the simplicity of earlier times. Until the 20th century somber colors and conservative cut characterized the costume of both men and women, and the women wore only kerchiefs on the head, or a special dark hood. No uniform costume was required although the power of tradition tended toward uniformity and resulted in an apparent uniform simplicity. The remoteness of the Russian Mennonite settlements from the major metropolitan centers of culture and commerce reduced the influence of changing fashions considerably.

The Mennonites of South Germany, Switzerland, and France, being largely rural and conservative, long retained the emphasis on simplicity in costume which characterized their earlier Anabaptist forebears, but in recent generations have adapted themselves generally to prevailing styles, though with a certain conservatism. No uniform dress regulations were ever developed, although the women, especially in Baden, wore a black fascinator-type veil instead of hats, both for general public wear and church wear until into the early 20th century.

American Mennonite Costume

It is reported that in 1727 "a large number of Germans, peculiar in their dress . . ." had settled on the Pequea, a Lancaster County stream (Rupp, 194). But in what the peculiarities consisted is not made clear. The earliest known description of the costume of the 18th century Mennonite immigrants to Pennsylvania (from the Palatinate), written by Redmond Conyngham in 1830 ("History of the Mennonites and Aymenists," ms.), but seemingly based upon earlier contemporary newspaper reports, whose authenticity cannot be checked, reads as follows: "The long beards of the men and the short petticoats of the females just covering the knee .... The men wore long red caps on their heads; the women had neither bonnets, hats, nor caps, but merely a string passing around the head to keep the hair from the face. The dress both of the female and the male was domestic, quite plain, and of coarse material, after an old fashion of their own." I. D. Rupp, a reliable historian of Lancaster County, Pa., says of the Mennonites in 1844, "They are distinguished above all others for their plainness of dress." L. J. Heatwole (b. 1852), a Mennonite bishop and historian in Virginia, describes the Mennonite costume of that area in earlier days (Christian Monitor, 1922, 592-93) as follows: "The early habits and customs of dress among pioneer Mennonites in Virginia were strictly in keeping with separation from the popular styles of their time. It is known that the men held to the universal color of drab for all their clothing. . . . The breeches however barely reached to the knees. ... The women wore the plain bodice, from which draped the linsey gown in comfortable folds to the feet, while the arms and shoulders were covered with a woolen home-made kerchief. The head was usually covered with a kerchief of homemade linen that was drawn close about the neck with corners tied under the chin."

It is evident that the American Mennonites of the colonial period (and on into the 19th century) dressed plainly, but there is no evidence that they then had a special uniform cut of coat for the men, or a peculiar form of headdress or costume for the women. Their difference from "the world" consisted of regulations proscribing luxuries and articles worn for display, such as lace collars, etc. Morgan Edwards (Baptists, 95) claimed in 1770 that the Mennonites were so strict in dress regulations that some had been expelled for wearing buckle shoes or outside coat pockets, but it is impossible to evaluate his report for accuracy. Since they lived in close proximity to the Quakers, who at this time had a distinctive garb for men and women which was very similar to that in time adopted by the Mennonites, it is quite possible that the Mennonites were influenced by them.

When long trousers for men came into general use, some of the older men, especially the ministers, clung to the old-fashioned knee breeches. The last minister of the Franconia Conference (MC) known to wear them died in 1834 (Wenger, Franconia, 286). Eventually all Pennsylvania Mennonites adopted long trousers, but they did not all adopt the modern sack coat with its short tail and lapels; the preachers and some of the laymen retained the use of the colonial plain-collared coat without turndown collar or lapels, and the ministers of the Mennonite Church (MC) in the Franconia, Lancaster, and Washington-Franklin conferences in the 1950s still wore the frock-tailed colonial coat.

Mennonite (MC) women in the Eastern United States and (some areas) elsewhere in the 1950s also wore a bonnet which used to be called a Quaker bonnet, the name being an indication of its probable origin. (The Pennsylvania Quakers adopted the bonnet around the year 1800; see Gummere, passim.) They also commonly wore what is called a "cape" over the shoulders, an article of dress which is probably an adaptation from the shawls which were current in the early decades of the 19th century. In the (MC) areas west of Pennsylvania fewer men wore the "plain coat," and the bonnet was no longer universally worn by 1955; in some areas only the older women retained its use. But the members as a whole opposed the use of jewelry, insisted on simplicity of attire, avoided the use of cosmetics, etc. The women generally wore their hair long. Furthermore, in worship the women wore a veil or cap, basing this on I Corinthians 11:2-16. In this group and related conservative groups the wedding ring was forbidden.

The position and practice of the Old Order Mennonites and of the Conservative Mennonite Church was similar to that of the Mennonite Church (MC), although more conservative and more uniform; there has been less deviation from practice in the 1950s.

The Old Order Amish and the Hutterian Brethren require beards of the men, a definite garb by both men and women, the use of hooks and eyes in place of buttons, the worship veil for the women, etc. In the East Amish men wear a flat, black, very broad-brimmed hat. The Hutterite women wear a black polka-dot kerchief as a worship veil, which they also wear at all times. The Old Order Amish women wear a white cap for a prayer veiling, which they also have their daughters wear from infancy, and wear shawls instead of coats, a holdover from the earlier universal women's costume.

The Church of God in Christ, Mennonite, requires the beard for men, not as a symbol of nonconformity (they have no garb), but because they believe this requirement to be a part of the permanent law of God. The women wear a black kerchief head-covering during worship.

The Evangelical Mennonites of Canada (Kleine Gemeinde) have no special garb, but stress general simplicity of dress, and in the 1950s the women wore a black kerchief headcovering during worship.

Other Mennonite bodies such as the General Conference Mennonite Church, the Evangelical Mennonite Brethren, the Evangelical Mennonite Church, the Mennonite Brethren, and the Missionary Church, have been traditionally conservative in dress and opposed to outward display in clothing, but in recent decades in America have tended more and more to follow the general conventions of society so that nonconformity in attire has largely become a dead letter; the members of these groups are not particularly distinguishable from non-Mennonites by their appearance. In these groups there are no specific church regulations proscribing the use of jewellery, requiring a worship veil, or forbidding the cutting of women's hair, and wedding rings are commonly worn.

The Old Colony, Sommerfelder, Rudnerweide, Bergthal, and Chortitz Mennonites of Manitoba and elsewhere are conservative groups in which the older traditions are strong, but in which there is little interpretation of cultural patterns in terms of specific Biblical teachings. The dress of members of the Old Colony, Sommerfelder, or Chortitz groups as worn to church services in the 1950s had the appearance somewhat of a prescribed uniform garb; the Chortitz men, for example, wore hooks and eyes. Some of the groups, Sommerfelder and Rudnerweide, e.g., permitted the wearing of the wedding ring. Short hair for women was frowned on in all these groups though it was not a test of membership in most of them. In many of the groups (such as Old Colony, Sommerfelder, and Chortitz) it is traditional for the women to wear a black kerchief (head shawl) during worship, but the average member would not associate this with any Biblical teaching on the veiling of women.

A review of the history of costume in the Mennonite congregations of Europe and America reveals that among the original Anabaptists and the stricter bodies of Mennonites in later centuries there was a strong sense of estrangement from "the world" which resulted in a deliberate nonconformity to the generally accepted cultural patterns of the current society. This involved the rejection of jewellery and anything worn for the display of wealth. In the course of time, especially among the Dutch Mennonites, this crystallized more or less into a garb in the stricter Mennonite groups. Eventually, however, much of the internal vigor of the European groups tended to disappear and the process of cultural accommodation continued until the whole concept of nonconformity to the world disappeared entirely and with it went usually not only nonconformity in dress but the practice of rejection of military service as well. In America the same processes have been at work, but some groups have withdrawn in reaction and settled into a formalism which tends to be devoid of spirituality; in these groups there is apt to be a feeling of contentment in being different in dress, etc., whether or not there is any inner spiritual life, evangelistic outreach, or program of missions and relief service to the needy of the world. Other groups have allowed the process of cultural accommodation to go on with little or no resistance, sincerely believing that Christianity does not consist in outward forms, but they have often tended to underestimate the power of the forces in contemporary society to mold the members of the brotherhood into the same types of character, belief, and practice, as are current in America in general. This has resulted in a loss of sense of unique mission as well as the partial surrender of basic Mennonite doctrines such as nonresistance. Groups of the first type, which lean toward formalism, have been labeled as "conservatives," and those of the second type, which tend to become more like American Protestants than the Mennonites have historically been, have been called "progressives." This leaves a third type (of which the largest group is the Mennonite Church (MC), the "moderates" (Smith, 744-46). These "moderates" constitute about two thirds of the entire Mennonite population of the Americas. They are attempting, though not always successfully, to maintain a vigorous inner sense of mission, and a voluntary simplicity of life which is applied even to their external appearance as described above. In this respect the "moderates" are seeking to have more of the type of spirituality which characterized their Anabaptist spiritual forebears with a truly Biblical separation unto God with its consequent nonconformity to the evil world about them, interpreting this nonconformity to apply to all areas of life. The Progressives have a similar concern for spirituality, but do not usually apply the principle of nonconformity to the dress area. Neither of these two groups today attempts to maintain a uniform garb, except in so far as the Eastern wing of the moderate group still strictly requires a uniform garb for women, though not consistently for men.

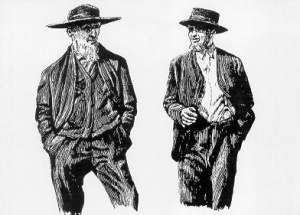

The special ministerial garb which in the 1950s was uniformly required in the Mennonite (MC) Church and the Conservative Amish in the 19th and 20th centuries, has no antecedent in earlier Mennonite Anabaptist history. It is probably a survival from earlier practice when all male members wore the distinctive garb. The origin of the special ministerial garb among the Old Colony Mennonites is obscure, but the garb has become stiffly fixed in tradition, ministers wearing a special coat and boots to the services. There is no connection between any of the special types of American Mennonite ministerial garb and the clerical garb of Roman priests or high-church Protestant clergymen of various denominations. Nor have Mennonite ministers any where in the world ever worn a gown in the pulpit, except in Danzig, where some of the pastors wore the clerical gown with the white neckbands; Jacob Mannhardt wore a special square cap (biretta). In certain North German churches (e.g., Hamburg, Emden, Danzig, Krefeld) and commonly in Dutch churches, the ministers wore (and in part still wear) special high black hats, gloves, and frock coat to the Sunday services. -- John C. Wenger

1990 Article

In the 1980s more than 120,000 people belonged to Anabaptist- and Mennonite-related groups in North and South America who require a distinctive style of dress for their members. There were also about 7,000 members of Brethren (i.e., Church of the Brethren, or Dunker) groups and a small remnant of Friends (Quakers) who wore plain garb. The Apostolic Christian Church continued to observe definite dress requirements both in North America and Europe.

Two distinctive dress features shared by most plain groups of Swiss Mennonite background are the plain coat and the cape dress. The plain coat has a standing collar and no lapels. The frock version of this coat has a split tail and usually no outside pockets. The cape on women's dresses covers the front and back of the bodice. The older style comes to a point in the back. This item is derived from the three-cornered kerchief.

By far the largest and most conservative group that maintains plain is the Old Order Amish church. Amish distinctives for men include: beards, hair cut off straight in the back and banged in front, wide-brimmed hats, suit coats and vest fastening with hooks and eyes, suspenders, and broadfall pants. Amish women customarily wear a headcovering with tie strings, uncut hair parted in the center and worn in a bun, a long dress with a pleated or gathered skirt, a cape, an apron, and black shoes and stockings. Bonnets and shawls are the approved outdoor garments. The Old Order Amish insist that all clothing be made of fabrics in solid colors and that there be no outside pockets on most clothing. Wrist watches are not allowed. There are many minor variations in dress among the different Amish communities. The "Nebraska" Amish of central Pennsylvania and the Swartzentruber Amish centered in Ohio are the most conservative.

The Beachy Amish Mennonite Fellowship continue to require beards for men and hooks and eyes for suit coats. Hats are seldom worn and broadfall pants and suspenders are no longer required in many congregations. Beachy Amish women wear tie strings on their head coverings and capes on their dresses but aprons are often omitted The Kauffman Amish Mennonites (Sleeping Preacher Amish) are similar to the Beachy Amish in dress although in some respects more conservative (the men wear longer beards) but in others more liberal (lapel coats with buttons are worn).

The Old Order Mennonites (buggy groups) have dress standards similar to those of the Amish. In contrast to the Amish the men have very short hair and do not grow beards, with a few exceptions in Ontario. Plain frock coats with buttons and vests with standing collars are standard for adult men in most churches. Women's dresses are typically made of printed fabric. The Pike or Stauffer Mennonite groups are the most conservative Old Order Mennonites. Men in these groups have longer hair and wider hat brims than other Old Order Mennonites.

Reformed Mennonite women traditionally dress in gray, including a large gray bonnet. The dress has a peplum on the bodice, a three-cornered cape, and an apron. Men are clean shaven, wear a plain frock coat, a plain hat, and a small black bow tie.

In reaction to the abandonment of plain dress in the Mennonite Church (MC) since the 1950s many groups have left the various Mennonite Church conferences to form independent groups and numerous unaffiliated churches. The Eastern Pennsylvania Mennonite Church, Fellowship Churches, Mid-West Mennonite Fellowship, Mid-Atlantic Mennonite Fellowship, the Southeastern Mennonite Conference, and the Washington- Franklin Mennonite Conference are the largest groups in this conservative Mennonite movement. The dress standards in these groups require plain coats for men and forbid neckties. Women are to wear cape dresses, headcoverings, uncut hair pinned up, and black stockings. Bonnets are frequently worn in some groups. Old Order Mennonites who permit automobiles dress similarly to the conservative Mennonites who withdrew from the Mennonite Church (MC) in the 1960s and 1970s.

Plain clothing has declined rapidly in the Mennonite Church (MC) since the 1950s, including Canadian congregations in Ontario and Alberta. West of the Allegheny Mountains dress regulations were abandoned earlier than in the East. In many congregations few, if any, women wear head coverings and no other distinctive dress is practiced. In the East the majority of Mennonite Church (MC) congregations dropped most dress regulations in the 1960s and 1970s. Many people born before the 1940s continue to observe the old standards. Some ministers in the Eastern United States still wear the plain coat although this is no longer mandatory.

A small minority of congregations in the Mennonite Church (MC) continue to prohibit women from cutting their hair and wearing slacks, shorts, and makeup. These churches also insist that the head covering (prayer veil) be worn consistently in public and that no jewellery be worn, including wedding bands. Plain coats and cape dresses are numerous but not obligatory. Some of the conservative congregations belonging to the Lancaster Conference (MC), where conservative congregations are most numerous within the Mennonite Church, organized the Keystone Mennonite Fellowship in 1987.

There has always been a diversity of dress practices in the Conservative Mennonite Conference. Since the 1950s nearly all the congregations that require the plain coat and cape dress have withdrawn from the Conservative Mennonite Conference. In the 1980s some churches that no longer require plain coats or cape dresses still do prohibit neckties and jewellery and do not allow women to cut their hair or go without a covering in public.

The Brethren in Christ had also emphasized plain dress for most of their history. During the first half of the 20th century men typically wore plain coats and hats and often beards. Women appeared in headcoverings, bonnets, and cape dresses. Plain clothing became part of the written discipline of the group in the 1930s. Beginning in the 1950s pressure to enter the evangelical mainstream caused rapid abandonment of plain clothing. By the 1970s very few Brethren in Christ wore distinctive garb. The same is true of the related United Zion Church.

The Old Order River Brethren continue to wear traditional garb. Men wear long beards and cut their hair straight off in back. Plain frock coats and wide brimmed hats are part of the attire. Women wear opaque white headcoverings, capes, aprons, and a peplum on the dress bodice.

Following World War II, but with increasing rapidity in the 1960s dress patterns changed in such groups as the Mennonite Church (MC) and Brethren in Christ which had had dress requirements. Many factors contributed to these developments: movement from rural to urban vocations; higher education; inroads of radio, television, and mass media, relaxing structures of traditional authority; and varied other forms of enveloping modernity.

In a time of transition and uneven resistance to change, dress regulations became a frequent and absorbing topic of discussion in family and congregational circles, evoking varying levels of concern and conflict. In the 1960s and 1970s a gradually increasing number of ministers and church leaders began appearing in public without the traditional ministerial garb.

The past generation of dress transition in the Mennonite (MC) and Brethren in Christ churches merits further study, particularly focusing on the following issues: (1) for groups with dress requirements comparison of rules for men and women; (2) women's perceptions on dress issues; (3) case studies in shifting dress patterns in particular congregations and church districts--including the role of open candid discussion and silent behavioral change; (4) case studies of individuals experiencing changing restrictions in dress; (5) comparative dress restrictions in other groups, e.g., Free Methodists, Aussiedler (emigrants) from Russia. -- Robert S. Kreider

Bibliography

Baehr, Karl. "Secularization Among the Mennonites of Elkhart County, Indiana." Mennonite Quarterly Review 16 (July 1942): 131-60.

Bossert, G., Sr. and G. Bossert, Jr. Herzogtum Württemberg. Leipzig, 1930: 691, 741, 806, 881.

Braght, Thieleman J. van. The Bloody Theater or Martyrs Mirror of the Defenseless Christians who Baptized Only Upon the Confession of Faith, and Who Suffered and Died for the Testimony of Jesus, their Saviour, from the Time of Christ to the year A.D. 1660. Scottdale, Pa. : Herald Press, 1950: 466, 495, 688, 789, 819, 841, 848, 898, 1001, 1061.

Brethren Encyclopedia. 1983: 399-404.

Complete Works of Menno Simons. Elkhart, IN: Mennonite Pub. Co., 1871: I, 21, 72, 97, 118, 175, 178, 185, 202, et passim.

Edwards, Morgan. Materials Toward a History of the American Baptists. Philadelphia, 1770.

Gingerich, Melvin. Mennonite Attire Through Four Centuries. Breinigsville, PA: Pennsylvania German Society, 1970.

Gummere, Amelia. The Quaker, a Study in Costume. Philadelphia, 1901.

Horsch, John Horsch. Mennonites in Europe. Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House, 1950: 251, 350, 368.

Horsch, John. Worldly Conformity in Dress. Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House, 1926.

Kessler, Johannes. Johannes Kesslers Sabbata. St. Gallen, 1902: 147 f.

Miller, E. Jane. "The Origin, Development, and Trends of the Dress of the Plain People of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania." M.S. Thesis, illustrated, Cornell University, 1943.

Rupp, I. Daniel. History of Lancaster County. Lancaster, 1844: 194.

Rupp, I. D. An Original History of the Religious Denominations . . . United States. Philadelphia, 1944.

Scott, Stephen. Why Do They Dress That Way? Intercourse, PA: Good Books, 1986.

Smith, C. Henry. The Story of the Mennonites. Newton, KS, 1950: 744-46.

Vincent, John M. Costume and Conduct in the Laws of Basel, Bern and Zurich, 1370-1800. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press, 1935: 19, 60, 85.

Wenger, J. C. Christianity and Dress. Scottdale, PA, 1943.

Wenger, J. C. Historical and Biblical Position of the Mennonite Church on Attire. Scottdale, PA, 1944.

Wenger, J. C. History of the Mennonites of the Franconia Conference. Telford, PA: 1938.

Wenger, J. C. Separated unto God. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1952: 139-51, 313-31.

Wittlinger, Carlton O. Piety and Obedience: The Story of the Brethren in Christ. Nappanee, IN: Evangel Press, 1978: 481-87.

| Author(s) | John C. Wenger |

|---|---|

| Robert S. Kreider | |

| Date Published | 1989 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Wenger, John C. and Robert S. Kreider. "Dress." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1989. Web. 3 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Dress&oldid=143395.

APA style

Wenger, John C. and Robert S. Kreider. (1989). Dress. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 3 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Dress&oldid=143395.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, pp. 99-104; vol. 5, pp. 246-247. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.