Furniture in Russia, Mennonite

Mennonites as a rule do not have furniture different from their neighbors, with exceptions from time to time when they were transplanted from country to country, and retained and developed patterns of their former home, just as they did in the realm of agricultural practices, architectural patterns, and other forms of culture. The fact that they usually came from a country with a higher culture into areas where they were pioneers necessitated their producing their own furniture, since markets were not accessible, or their pioneer conditions did not make it possible for them to buy expensive furniture. This must have been the case in Prussia when, during the 16th century, Dutch Mennonite settlers established themselves along the Vistula River, and again when their descendants began to move into Poland and Russia. In the prairie states of America, this tradition was soon given up for various reasons. In the early days in Manitoba, Mexico, and Paraguay, the Mennonites continued to make their own furniture after traditional patterns.

The furniture used in traditional Mennonite homes of the Prusso-Russian background was closely related to the pattern of the house. Each room served a special purpose and had its corresponding furniture, which was always the same. Only slight and gradual deviations occured depending on economic conditions and size of family. Some of the best descriptions of interior arrangements and furniture of this tradition can be found in Arnold Dyck's Verloren in der Steppe (English, Lost in the Steppe)and Peter Epp's Eine Mutter, as well as in the article by W. Schmiedehaus, "Mennonite Life in Mexico" (Mennonite Life, April 1947, 29).

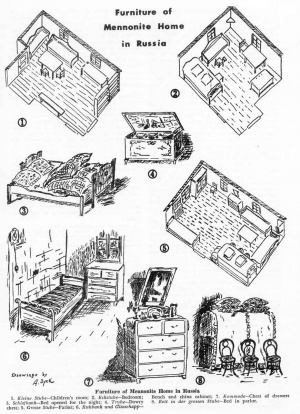

Entering a traditional Mennonite home of Prussia, Russia, Manitoba, Mexico, and Paraguay through the front door, one enters the front hall (Vorhaus), from which one proceeds to the back hall (Hinterhaus), which leads into the kitchen and into the Kleine Stube (see drawing No. 1). This room is usually occupied by day and night by the youngest children, has a table and two beds called the Schlafbank, which during the day are used as benches. At night the lid is opened and the benches are pulled out and serve as double beds (see drawing No. 3). The next room is the Eckstube (see drawing No. 2). This is the bedroom of the parents. It has a bed in which the bedding is kept, topped by the two pillows. For the night it is pulled out to make a double bed just like the Schlafbank (see drawing No. 3). In this room there is also a Ruhbank, a bench located under the window and used for sitting and resting, a large traditional dowry chest containing heirlooms, etc. (see drawing No. 4), a table, and some chairs. From this room one proceeds to the parlor or grosse Stube (see drawing No. 5), which is used only when exceptional guests come. It contains, right next to the brick stove which heats all three rooms, a bench called the Ofenbank which is used for resting. Right above the bench is a traditional Mennonite clock. At the other end next to the wall is the china closet, called Glausschaup (see drawing No. 6), containing traditional china inherited from the parents to which occasionally items are added as a birthday present. Between the windows toward the front yard stands a chest of drawers, above which hangs a large mirror (see drawing No. 7). Toward the inner wall stands a bed filled almost to the ceiling with bedding and topped with pillows (see drawing No. 8); in front of it are some chairs. This is used when guests come. This room also has a table. Next to it in the corner is the wardrobe, called Kleedaschaup, where the family's Sunday clothes are kept. The closet is made after patterns dating far back into the early history of the Mennonites in Prussia. Another door from here leads to the front hall. Next to the front hall on the opposite side is the room for the grown boys, called the Sommerstube, which contains a bed, table and chairs, and possibly some tools for carpenter work.

All this furniture was made in the home carpenter shops. Not every farmer was a carpenter but some who had the inclination, ability, and time made these pieces of furniture for themselves and also for their neighbors. In some communities there were carpenter shops which served the entire community. This is also the case in Manitoba, Mexico, and South America. Naturally, with economic progress, some families preferred to buy the furniture in use in their respective countries. This was the case to some extent in Russia, but particularly in the United States, and also in Canada. To what an extent the Mennonites of Prussia had retained these patterns or when they disappeared or where modified is still to be investigated.

See also Architecture

| Author(s) | Cornelius Krahn |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1956 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Krahn, Cornelius. "Furniture in Russia, Mennonite." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1956. Web. 12 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Furniture_in_Russia,_Mennonite&oldid=94782.

APA style

Krahn, Cornelius. (1956). Furniture in Russia, Mennonite. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 12 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Furniture_in_Russia,_Mennonite&oldid=94782.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, pp. 424-426. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.