Apologetics

The Anabaptists did not see themselves as theologians, certainly not as formal theological apologists. They looked with great suspicion on learned theologians who could give erudite arguments on doctrine, but whose lives were not in harmony with the spirit of Christ. They did, however, engage in polemics and in apologetic discourse for several significant reasons. (1) They were forced to do so by their opponents who brought charges of heresy against them. (2) They were enjoined by Scriptures (1 Peter 3:15) to give an answer for their faith to anyone who asked. (3) They made universal claims for the gospel they preached. They engaged freely in normative discourse and sought to confront all people with the claims of the gospel. (4) They felt a sense of mission to all who named the name of Jesus and were free to engage any and all Christians in mutual discussion, study, exhortation, warning, and action on the basis of the Word of God. (5) Such exhortation, discussion and mutual exhortation was seen as necessary in arriving at an understanding of God's will. (6) They tried, often in vain, to answer gross misunderstandings and misrepresentations about themselves, and (7) they sought to answer such false charges so that they could convince people of their biblical orthodoxy and thus avoid being executed for sound biblical faith and life.

The Anabaptists did not try to explicate a rationally coherent body of propositional truths. They sought rather to understand and proclaim God's work in the world; to proclaim the way of salvation as they understood it and to live as disciples of Jesus Christ. They tried in all simplicity to give a reason for their faith (1 Peter 3:15).

Scan provided by the Mennonite Archives of Ontario.

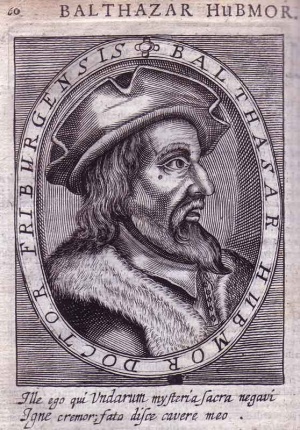

From the beginning and throughout the 16th century, the Anabaptists had to defend themselves against polemical attacks from four different directions -- Roman Catholics, Lutherans, Reformed, and from within. Though the Catholics saw them as one with all Protestants, adult baptism was the central issue in the Roman Catholic debate with the Anabaptists. Johannes Faber challenged Balthasar Hubmaier who yielded to Faber on many of the issues raised, but not on baptism and communion. Other exchanges were between Martinus Duncanus and the Anabaptists; Christoph Erhard against the Hutterites, to which Klaus Braidl replied; Franciscus Casterns against Jacob P. van der Meulen, who also replied. The Hutterites were particularly hard pressed by the Catholics because of the strength of the Counter Reformation in Moravia during the 1600s. Leonhard Dax, a Hutterite, wrote Noble Lessons and Instructions in the 1560s in answer to Catholic charges. Menno Simons devoted a section to the refutation of Roman Catholic doctrine in his Foundations of Christian Doctrine (1539, Writings, 142-90).

A second line of defense was against Lutheran attacks. Though Martin Luther himself had little to do with the Anabaptists, and was not at all well informed about them, he nevertheless advised two pastors on how to answer the Anabaptists' teaching on baptism (1528). Philipp Melanchthon also wrote against the Anabaptists in 1528 and 1535 on topics of baptism, the Lord's Supper and community of goods. In 1557 the Lutherans and Catholics consulted together at Worms on how to answer the Anabaptist threat. Their findings were given in a document signed by Melanchthon, Johannes Brenz, Jakob Andreae, and others. Anabaptists responded to it through Leonhard Dax's Refutations, a 107 page booklet that systematically refuted each of the charges.

The main line of defense of the Anabaptists was against the Reformed, since they were the dominant group in Switzerland and The Netherlands. Two of Calvin's books were directed against the Anabaptists: Psychopannychia (1542), in which Calvin wrote against the doctrine of soul sleep, widely held among the French Anabaptists; and Brieve Instruction.... (1544), which sought to refute the seven articles of the Schleitheim Confession, soul sleep, and the Anabaptists' view of the incarnation. The Anabaptists, on their part, spoke against infant baptism, oaths, hearing of arms, service in government office, and in favor of avoidance, or the ban. Taking part on the Reformed side were Ulrich Zwingli especially on baptism; Heinrich Bullinger; Gellius Faber; John à Lasco; and Martinus Micronius. Anabaptists who answered were Menno Simons, Balthasar Hubmaier, Pilgram Marpeck and Leonhard Dax.

A further line of defense was directed against error from within their own ranks and from other "sectarian" groups. Pilgram Marpeck wrote Verantwortung as a reply to Caspar von Schwenckfeld, a spiritualist, emphasizing the humanity of Christ which Schwenckfeld neglected; Balthasar Hubmaier wrote On the Sword to differentiate his views from the Stabler groups in Nikolsburg; Menno Simons' Confessions of the Triune God (1550, Writings, 489-498) was directed against Adam Pastor's views of Christ, and Menno's Reply to Sylis and Lemke (1560, Writings, 1001-15) was directed against those south German Mennonites who disagreed with Menno on the ban, and especially on marital avoidance.

Beyond this, the Anabaptists had to defend themselves against other common accusations and misrepresentations: that they were revolutionaries, like the Münster Anabaptists; that they practiced polygamy, held things in common, were too severe in church discipline; that they were schismatic; and that they were legalists. These and other accusations were dealt with in Menno Simons' Reply to False Accusations (1552, Writings, 541-78).

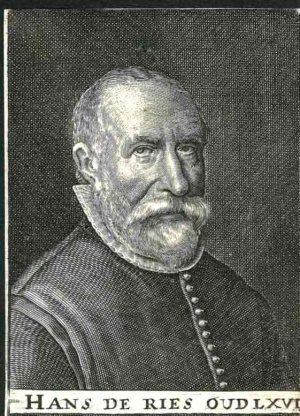

During the 17th century the main apologetic activity was centered in The Netherlands, where Anabaptists still needed to defend themselves against Calvinism. Calvinist books against Anabaptists were published from 1565 to 1671 and as late as 1757. Anabaptism was defended by Claes Claesz, Anthoni Jacobsz Roscius, E. A. van Dooresgeest, and Galenus Abrahamsz. Hans de Ries wrote his Apologia in 1626 and earlier published 40 articles of faith together with Lubbert Gerritsz (1618). He had already helped to draw up articles of faith (38 articles), which were published in 1561. The period from 1615 to 1665 was immensely productive of confessions of faith by the Dutch Mennonites. They were attempts to heal schisms among them and to unite the fellowship. At the same time, they were meant to differentiate the Mennonite understanding of faith from the predominant Calvinist view. Of special note is T. T. van Sittert's apology for the Anabaptist-Mennonite tradition in 1664. He made a strong defense for adult baptism, nonresistance, the refusal to swear oaths, subjection to the state, and a plea for tolerance.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, there is very little that could be called apologetic writing or discussion by Mennonites. With increasing toleration and the shifting of concern for the faith to questions of the Enlightenment, the parties that earlier debated against each other, now had to defend themselves against a totally new front, and were, in a sense, allies rather than opponents.

So also the Martyrs' Mirror of 1660 was designed to inspire the Mennonite Christians to consider their own faith, probably because that faith was no longer sustained by overt persecution. Theological disputations were no longer held, Calvinist books against Anabaptists were few, and complaints to the government decreased. The most frequent charge against Mennonites was that they were Socinians. The Mennonites in the 18th-19th centuries did not concern themselves with the challenges to orthodoxy coming from the universities of that time: historical-critical interpretation, the relation of science and Scripture, and other issues arising out of the Enlightenment.

At the turn of the 19th-20th centuries, during the Modernist-Fundamentalist controversy, Mennonite scholars were forced to differentiate themselves both from Liberal theology and from Fundamentalist dispensationalist theology, both of which bad made some inroads into Mennonite thought and practice. John Horsch wrote The Failure of Modernism, and Daniel Kauffman wrote Doctrines of the Bible to affirm an evangelical faith and yet state clearly Mennonite teachings on adult baptism, nonresistance, the non-swearing of oaths, and other doctrines not emphasized by the Fundamentalists.

In the 20th century the main polemical and apologetic writings came from John Howard Yoder. He offered a strong emphasis on peace and nonresistance as the heart and center of a true understanding of the saving work of Christ. His apologetics for a new understanding of the faith, in harmony with the Anabaptist and Mennonite tradition, addressed the entire spectrum of theological positions in North America and abroad.

The disputes or apologies were inevitable. Disputants came with their own presuppositions, biblical principles, and approach to the Scriptures. The Anabaptists began with a set of presuppositions not shared by the Protestant Reformers or the Catholic theologians. Basic to their apologetics were the following: (1) Jesus Christ is the full and final revelation of God. Jesus is Lord and is to be followed in life. (2) An important distinction is to be made between the Old Testament and the New Testament. They relate as promise and fulfillment, shadow and reality, preparation and actualization. (3) The church is the body of Christ; i.e., the visible embodiment of Christ in the world. Thus Christians must live a Christ-like life, and follow the Lord in his obedience, suffering and, if necessary, death. (4) The church is the community in which the will of God is discerned -- a hermeneutic community. The word of God is not established by papal decree, or by theologians, but by the corporate community directed by the Holy Spirit of God. (5) The Scriptures best interpret the sense of Scripture and no extra-biblical appeals to nature, philosophy, or the state can be made. (6) The end of the age is at hand, when the works of all humans will be rewarded according to their faith and works.

The Anabaptists insisted on certain prerequisites in understanding the Bible and the will of God. (1) Apart from regeneration by the Holy Spirit, the new birth, no one can rightly understand and interpret the Scriptures. This new birth was seen as a commitment to Christ made by adults, on the basis of repentance and faith, and, therefore, could not be made by an infant. (2) People have to come to the Scriptures in a proper spirit in order to understand its message and call. Only those who truly wish to know the will of God, and open themselves to the leading of the Spirit will hear the word of God. (3) Only those who are obedient to Christ and follow him in newness of life will be led by the Spirit into all truth. (4) The church must be willing to preach the word of God and to exhort on the basis of that word if the Spirit is to work in the fellowship. Only as the church is willing to actually loose and bind (discipline) its members, can it fully know the truth of God.

Specific principles of interpretation also set the Anabaptists apart front their contemporaries. (1) Christocentrism in interpretation was not new, but it was applied differently by the Anabaptists. They did not ask "What promotes Christ" (was Christum treibet) so as to make judgments about which Scriptures promoted Christ, but rather evaluated all of Scripture through the revelation received in Christ. The controlling principle of biblical interpretation was the proper understanding of the life and ministry of Jesus. (2) A clear distinction had to be made between the Old and the New Testaments. The Old Testament history and revelation was preparatory and culminated in Jesus, who was the fulfillment of the Old Testament prophecies and of God's actions in Israel's history. A new reality came into being through Christ. The Anabaptists acknowledged that there was a progressive understanding of the work of God culminating in God's revelation in Jesus Christ. (3) The word of God was not restricted to or confined to the Bible. The Bible was God's chief way of sharing the word of God with humankind, but the Spirit could speak directly to people, and the word of God could be proclaimed by others in preaching and admonition. Nevertheless, all such revelations remained subject to and had to be judged by the revelation of Christ as given in the Scripture. (4) This necessitated making a distinction between the "inner" and "outer" word; to distinguish letter and spirit. The Anabaptists were accused of being literalists (for they insisted that the simplicity and clarity of the text did not require professional interpreters) and of relying too much on the Spirit (because of the insistence that all interpretation must be guided by the Holy Spirit). The interpretation of Scripture without the personal appropriation of its message and truth, would result in a dead letter. There had to be an inner response to the message. (5) The Anabaptists insisted on corporate discerning of the will of God. Each person had to be encouraged and supported to follow Christ in life. Each person's spirit, insight, and life had to be tested to see if it conformed to the Spirit of Christ. The details of what it meant to follow Christ were discerned in the fellowship of believers. The loosing (freeing from bondage) and binding (binding to the will of God) function of the church was seen as part of being the church of Christ.

Bibliography

Balke, Willem. Calvin and the Anabaptist Radicals. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1981.

Bender, H.S. "The Discipline Adopted by the Strasburg Conference of 1568." Mennonite Quarterly Review 1 (1927): 61-90.

Burkholder, J. R. and Calvin Redekop, eds., Kingdom Cross and Community. Scottdale, 1976.

Dyck, C. J. "The Suffering Church in Anabaptism." Mennonite Quarterly Review 59 (1985): 5-23.

Ewert, Wilhelm. "A Defense of the Ancient Mennonite Principle of Nonresistance by a Leading Russian Mennonite Elder in 1873." Mennonite Quarterly Review 11 (1937): 284-90.

Fischer, Hans Georg. "Lutheranism and the Vindication of the Anabaptist Way." Mennonite Quarterly Review 28 (1954): 27-38.

Friedmann, Robert. "Claus Felsinger Confession of 1560." Mennonite Quarterly Review 29 (1955): 141-61.

Gross, Leonard. The Golden Years of the Hutterites. Scottdale, 1980.

John Calvin: Treaties against the Anabaptists and against Libertines, trans. B.W. Farley. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1982.

Hershberger, Guy F., ed. Recovery of the Anabaptist Vision. Scottdale, 1959.

Hillerbrand, Hans J. "Thomas Müntzer's Last Tract Against Martin Luther." Mennonite Quarterly Review 38 (1964): 20-36.

Horsch, John. The Failure of Modernism: a Reply to Harry Emerson Fosdick. Chicago, 1925.

Klaassen, Walter, ed. Sixteenth Century Anabaptism Defences, Confessions, Refutations, trans. Frank Friesen. Waterloo, Ont. : Conrad Grebel College, 1982.

Klaassen, Walter. Anabaptism: Neither Catholic nor Protestant. Waterloo: Conrad Press, 1973.

Klaassen, Walter. "Speaking in Simplicity: Balthasar Hubmaier." Mennonite Quarterly Review 40 (1966): 139-47.

Klaassen, Walter. "The Berne Debate of 1538: Christ the Center of Scripture." Mennonite Quarterly Review 40 (1966): 148-56.

Klassen, William and Walter Klaassen, eds. and trans. The Writings of Pilgram Marpeck. Scottdale, Pa., 1978.

Klassen, William. "The Hermeneutics of Pilgram Marpeck." Diss., Princeton Theological Seminary, 1960.

Klassen, William. Covenant and Community: the Life, Writings and Hermeneutics of Pilgram Marpeck. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1968.

Klassen, William. "The Limits of Political Authority, as Seen by Pilgram Marpeck." Mennonite Quarterly Review 56 (1982): 342-64.

Koontz, Gayle Gerber. "Confessional Theology in a Pluralistic Age: a Study of the Theological Ethics of H. Richard Niebuhr and John Howard Yoder. PhD diss., Boston U. 1985.

Krahn, Cornelius. Dutch Anabaptism. Scottdale, 1981.

Krahn, Cornelius. "The Emden Disputations." Mennonite Quarterly Review 30 (1956): 2,56-58.

Krebs, M. and H.G. Rott, eds. Quellen zur Geschichte der Täufer, vol. 7-8. Elsaß 1-2, Stadt Straßburg. Gütersloh, 1959-1960.

Krebs, M., ed. Quellen zur Geschichter der Täufer, vol. 4: Baden und Pfalz. Gütersloh, 1951.

Littell, Franklin Hamlin. The Anabaptist View of the Church. American Society of Church History, 1952.

Loserth, J. Quellen und Forschungen zur Geschichte der oberdeutchen Taufgesinnten im 16. Jahrhundert. Leipzig, 1929.

Matthijssen, Jan P. "The Bern Disputation of 1538." Mennonite Quarterly Review 22 (1948): 19-33.

Menno Simons, The Complete Writings of Menno Simons, c. 1496-1561, trans. Leonard Verduin, ed. J.C. Wenger. Scottdale, 1956.

Oyer, John S. Lutheran Reformers Against Anabaptists. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1964.

Peachy, Paul, ed. "Answer of Some Who are Called (Ana) Baptists; Why They do not Attend the Churches; a Swiss Brethren Tract." Mennonite Quarterly Review 45 (1971): 5-32.

Philips, Dirk (Dietrich). Regeneration and the New Creature, Spiritual Restitution and the Church of God. Berne: Light and Hope, 1958.

"Pilgram Marpeck's Confession of Faith, 1531." Mennonite Quarterly Review 12 (1938):167-202.

Poettcker, Henry. "The Hermeneutics of Menno Simons." ThD diss., Princeton Theological Seminary, 1961.

Riedemann, Peter. Account of Our Religion, Doctrine and Faith, trans. Kathleen E. Hasenberg. London: Hodder and Stoughton, and Plough Publishing House, 1938, 1950, 1970.

Stupperich, Robert, ed., Die Schriften Bernhard Rothmanns. Münster in W. : Aschendorff, 1970.

Swartley, Willard, ed., Essays on Biblical Interpretation. Elkhart, Ind.: Institute of Mennonite Studies, 1984.

Wenger, John C., trans. and ed. "T. T. Van Sittert's Apology for the Anabaptist-Mennonite Tradition, 1664." Mennonite Quarterly Review 49 (1975): 521.

Wenger, John C. "The Schleitheim Confession of Faith." Mennonite Quarterly Review 19 (1945): 243-53.

Wenger, John C. "Martin Weninger's Vindication of Anabaptism, 1535." Mennonite Quarterly Review 22 (1948): 180-87.

Westin, G. and Torsten Bergsten, eds. Balthasar Hubmaier Schriften. Gütersloh, 1962.

Wiswedel, Wilhelm. "The Anabaptists Answer Melanchthon." Mennonite Quarterly Review 29 (1955): 212-23.

Yoder, Jessie. "The Frankenthal Debate with the Anabaptists in 1571: Purpose, Procedure, Participants." Mennonite Quarterly Review 36 (1962): 14-35, 116-46.

Yoder, John H., ed. and trans. The Legacy of Michael Sattler. Scottdale, Pa., 1973.

Yoder, John H. The Priestly Kingdom. U. of Notre Dame Press, 1984.

Yoder, John H. The Christian Witness to the State. Newton, 1964.

Yoder, John H. The Politics of Jesus. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1972.

Zijpp, N. van der. "The Confessions of Faith of the Dutch Mennonites." Mennonite Quarterly Review 29 (1955): 171-87.

| Author(s) | David Schroeder |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1989 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Schroeder, David. "Apologetics." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1989. Web. 18 Dec 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Apologetics&oldid=117895.

APA style

Schroeder, David. (1989). Apologetics. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 18 December 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Apologetics&oldid=117895.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 5, pp. 30-33. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.