Difference between revisions of "Westphalia (Germany)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m (Text replace - " <em>Martyrs' Mirror</em>" to " <em>Martyrs' Mirror</em>") |

SusanHuebert (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

=== Introduction === | === Introduction === | ||

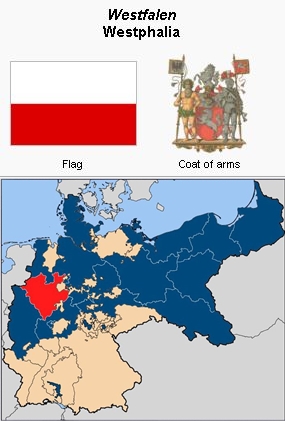

| − | Westphalia (<em>Westfalen</em>), a former province (area 7,806 sq. miles, 1939 pop. 5,200,000) of Prussia, [[Germany|Germany]], of which the chief cities are Münster, [[Bielefeld (Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)|Bielefeld]], Hamm, Bocholt, Paderborn, and those of the Ruhr Valley. The geographic boundaries of the territory called Westphalia have in the past been flexible and often changed according to the political and religious constellations of the day. [[Anabaptism|Anabaptism]] in Westphalia has primarily become known in connection with the radical [[Münster Anabaptists|Münsterite]] Anabaptism. Less known is the fact that after the end of the Münsterite movement in 1535 Anabaptism survived in various cities and communities in Westphalia. These Anabaptists, commonly known as "Mennisten" or "Tibben", had very little or nothing in common with the radical Münsterites. At the time of the [[Reformation, Protestant|Reformation]] Westphalia had three bishoprics, Münster, Minden, and Paderborn, and the abbeys Korvey and Herford, which were religious territories subject directly to the emperor. Secular entities were [[Cleves, Duchy of|Cleves]] and the Duchy of Westphalia. Many of the cities of the province enjoyed great freedom. These territorial conditions determined to a large extent the outcome of the denominational lines of the province, in accordance with the | + | Westphalia (<em>Westfalen</em>), a former province (area 7,806 sq. miles, 1939 pop. 5,200,000) of Prussia, [[Germany|Germany]], of which the chief cities are Münster, [[Bielefeld (Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)|Bielefeld]], Hamm, Bocholt, Paderborn, and those of the Ruhr Valley. The geographic boundaries of the territory called Westphalia have in the past been flexible and often changed according to the political and religious constellations of the day. [[Anabaptism|Anabaptism]] in Westphalia has primarily become known in connection with the radical [[Münster Anabaptists|Münsterite]] Anabaptism. Less known is the fact that after the end of the Münsterite movement in 1535 Anabaptism survived in various cities and communities in Westphalia. These Anabaptists, commonly known as "Mennisten" or "Tibben", had very little or nothing in common with the radical Münsterites. At the time of the [[Reformation, Protestant|Reformation]] Westphalia had three bishoprics, Münster, Minden, and Paderborn, and the abbeys Korvey and Herford, which were religious territories subject directly to the emperor. Secular entities were [[Cleves, Duchy of|Cleves]] and the Duchy of Westphalia. Many of the cities of the province enjoyed great freedom. These territorial conditions determined to a large extent the outcome of the denominational lines of the province, in accordance with the principle <em>cuius regio eius religio</em>. In 1947 the province of North Rhine-Westphalia (<em>Nordrhein-Westfalen</em>) was formed. |

The Lutheran reform movement reached Westphalia, particularly the eastern parts, in the early days of the Reformation. In the western part in places like Jülich and Cleves the Reformed influences became more noticeable. In the Duchy of Westphalia the Reformation came to a stop when Hermann von Wied, Bishop of Cologne, abdicated in 1547. [[Philipp I, Landgrave of Hesse (1504-1567)|Philipp of Hesse]] exerted considerable influence in some parts. In the city of Münster various forces paved the way for the Reformation, some coming from [[Luther, Martin (1483-1546)|Luther]], others from the Lower Rhine and the Netherlands until the city was converted into a radical Anabaptist "New Jerusalem" which was liquidated in 1535 by the Bishop of Münster, Franz von Waldeck. All Anabaptism, everywhere, even if it had nothing to do with the "New Jerusalem," had received a setback from which it never recuperated, particularly in Westphalia. Keller's three-volume work, <em>Die Gegenreformation in Westfalen und am Niederrhein</em>, is to a considerable extent a record of the heroic struggle for survival by peaceful Anabaptism in the province of Westphalia. The Reformed and the Lutheran churches were, of course, witnessing in a similar way. Yet in his presentation of <em>Der Kampf um eine evangelische Kirche im Münsterland 1520-1802,</em> Friedrich Brune finds the evangelical movement closely interwoven with Anabaptism, particularly in the beginning, and his book is therefore also to some extent a history of Anabaptism in the rural areas of Münster seen from a Lutheran point of view. | The Lutheran reform movement reached Westphalia, particularly the eastern parts, in the early days of the Reformation. In the western part in places like Jülich and Cleves the Reformed influences became more noticeable. In the Duchy of Westphalia the Reformation came to a stop when Hermann von Wied, Bishop of Cologne, abdicated in 1547. [[Philipp I, Landgrave of Hesse (1504-1567)|Philipp of Hesse]] exerted considerable influence in some parts. In the city of Münster various forces paved the way for the Reformation, some coming from [[Luther, Martin (1483-1546)|Luther]], others from the Lower Rhine and the Netherlands until the city was converted into a radical Anabaptist "New Jerusalem" which was liquidated in 1535 by the Bishop of Münster, Franz von Waldeck. All Anabaptism, everywhere, even if it had nothing to do with the "New Jerusalem," had received a setback from which it never recuperated, particularly in Westphalia. Keller's three-volume work, <em>Die Gegenreformation in Westfalen und am Niederrhein</em>, is to a considerable extent a record of the heroic struggle for survival by peaceful Anabaptism in the province of Westphalia. The Reformed and the Lutheran churches were, of course, witnessing in a similar way. Yet in his presentation of <em>Der Kampf um eine evangelische Kirche im Münsterland 1520-1802,</em> Friedrich Brune finds the evangelical movement closely interwoven with Anabaptism, particularly in the beginning, and his book is therefore also to some extent a history of Anabaptism in the rural areas of Münster seen from a Lutheran point of view. | ||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

=== After "Münster" === | === After "Münster" === | ||

| − | In the city of Münster, [[Roman Catholic Church|Catholicism]] was fully restored after 1535, but Philipp of Hesse insisted that at least one or two evangelical ministers be permitted to preach. Anabaptists, of course, were not permitted in the city. Münster, however, had lost the political, intellectual, and religious liberties it had enjoyed under the guilds that were now forbidden. In the surrounding towns and communities of | + | In the city of Münster, [[Roman Catholic Church|Catholicism]] was fully restored after 1535, but Philipp of Hesse insisted that at least one or two evangelical ministers be permitted to preach. Anabaptists, of course, were not permitted in the city. Münster, however, had lost the political, intellectual, and religious liberties it had enjoyed under the guilds that were now forbidden. In the surrounding towns and communities of Ahlen, Warendorf, Dolmen, [[Coesfeld (Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)|Coesfeld]], Ahaus, Vreden, Bocholt, Borken, and [[Freckenhorst (Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)|Freckenhorst]], not only Protestantism but also Anabaptist congregations survived at places for a century. |

In [[Warendorf (Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)|Warendorf]], where Anabaptism found entry in 1534, one of the Anabaptist preachers was [[Klopreis, Johann (d. 1535)|Johann Klopreis]]. More than fifty persons were baptized here. The city council was sympathetic toward Anabaptism until Franz von Waldeck interfered. The monastery Freckenhorst near Warendorf, which became Protestant in 1532, was an Anabaptist stronghold. In Coesfeld Anabaptism was established in 1534. Some followers went to Münster. In [[Dülmen (Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)|Dülmen]] the evangelical movement and Anabaptism were started through the preaching of [[Rothmann, Bernhard (ca. 1495- ca. 1535)|Bernhard Rothmann]]. Two ministers from Münster were invited to promote the preaching of the Gospel there but were stopped by the bishop. In Vreden there were "several sects" who met outside the city in the barns and groves and practiced "their unusual baptism" (Brune). | In [[Warendorf (Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)|Warendorf]], where Anabaptism found entry in 1534, one of the Anabaptist preachers was [[Klopreis, Johann (d. 1535)|Johann Klopreis]]. More than fifty persons were baptized here. The city council was sympathetic toward Anabaptism until Franz von Waldeck interfered. The monastery Freckenhorst near Warendorf, which became Protestant in 1532, was an Anabaptist stronghold. In Coesfeld Anabaptism was established in 1534. Some followers went to Münster. In [[Dülmen (Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)|Dülmen]] the evangelical movement and Anabaptism were started through the preaching of [[Rothmann, Bernhard (ca. 1495- ca. 1535)|Bernhard Rothmann]]. Two ministers from Münster were invited to promote the preaching of the Gospel there but were stopped by the bishop. In Vreden there were "several sects" who met outside the city in the barns and groves and practiced "their unusual baptism" (Brune). | ||

| − | Bocholt also had special significance for the Anabaptists: a meeting of the surviving groups took place in 1536 in which [[David Joris (ca. 1501-1556)|David Joris]] | + | Bocholt also had special significance for the Anabaptists: a meeting of the surviving groups took place in 1536 in which [[David Joris (ca. 1501-1556)|David Joris]] seems to have been dominant. [[Adam Pastor (d. 1560/70)|Adam Pastor]], for a while a co-worker of Menno Simons, came from "Dorpen" in Westphalia, evidently the village of Dörpen on the Ems in the northern part in the bishopric of Münster. On [[Menno Simons (1496-1561)|Menno Simons]]' journey from [[East Friesland (Niedersachsen, Germany)|East Friesland]] to Cologne in 1545 and also when he returned to Lübeck in 1546 he may have passed through Westphalia. |

=== Cleves-Mark === | === Cleves-Mark === | ||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

=== Later Period === | === Later Period === | ||

| − | To what an extent, if any, the membership of the [[Gronau Mennonite Church (Gronau, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)|Mennonite Church of Gronau]] is of old Westphalia Anabaptist stock is not known. In any event this is the oldest Mennonite church in Westphalia. It was organized 4 February 1888, in Gronau, 32 miles northwest of Münster, by about 20 Mennonite families living in Gronau and Ahaus, where a large Mennonite industrial center has since developed. After World War II a number of Mennonite refugees joined the congregation. It was also the gateway for thousands of others who went to [[Canada|Canada]]. After World War II numerous Mennonites from | + | To what an extent, if any, the membership of the [[Gronau Mennonite Church (Gronau, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)|Mennonite Church of Gronau]] is of old Westphalia Anabaptist stock is not known. In any event this is the oldest Mennonite church in Westphalia. It was organized 4 February 1888, in Gronau, 32 miles northwest of Münster, by about 20 Mennonite families living in Gronau and Ahaus, where a large Mennonite industrial center has since developed. After World War II a number of Mennonite refugees joined the congregation. It was also the gateway for thousands of others who went to [[Canada|Canada]]. After World War II numerous Mennonites from eastern Germany and some from [[Poland|Poland]] and [[Russia|Russia]] settled in Westphalia, and have organized churches in several places. The Bergisches Land congregation was organized in 1948 in Niederar-Ahe; it includes also the Sauerland area and has a baptized membership of 199. The elder of the church in the late 1950s was Fritz Marienfeld. The congregation at [[Espelkamp (Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)|Espelkamp]], organized in 1952, had its own meetinghouse and a baptized membership of 150 in the late 1950s. |

Another congregation, the Mennonite Church of Westphalia, met at various places during the late 1950s, such as [[Osnabrück (Niedersachsen, Germany)|Osnabrück]], Münster, Recklinghausen, [[Bielefeld (Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)|Bielefeld]], Brakel, and Detmold, and had a membership of 600. | Another congregation, the Mennonite Church of Westphalia, met at various places during the late 1950s, such as [[Osnabrück (Niedersachsen, Germany)|Osnabrück]], Münster, Recklinghausen, [[Bielefeld (Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)|Bielefeld]], Brakel, and Detmold, and had a membership of 600. | ||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

Crous, Ernst. "Die rechtliche Lage der Krefelder Mennonitengemeinde im 17. u. 18. Jh.," <em>Beitrage zur Gesch. rhein. Mennoniten. Weierhof</em>. 1939: 40. | Crous, Ernst. "Die rechtliche Lage der Krefelder Mennonitengemeinde im 17. u. 18. Jh.," <em>Beitrage zur Gesch. rhein. Mennoniten. Weierhof</em>. 1939: 40. | ||

| − | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. <em>Mennonitisches Lexikon</em>, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. IV. | + | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. <em>Mennonitisches Lexikon</em>, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. IV, 498-502. |

Keller, Ludwig. <em>Die Gegenreformation in Westfalen und am Niederrhein</em>, 3 vols. Leipzig, 1881-95. | Keller, Ludwig. <em>Die Gegenreformation in Westfalen und am Niederrhein</em>, 3 vols. Leipzig, 1881-95. | ||

Revision as of 16:35, 23 August 2016

Introduction

Westphalia (Westfalen), a former province (area 7,806 sq. miles, 1939 pop. 5,200,000) of Prussia, Germany, of which the chief cities are Münster, Bielefeld, Hamm, Bocholt, Paderborn, and those of the Ruhr Valley. The geographic boundaries of the territory called Westphalia have in the past been flexible and often changed according to the political and religious constellations of the day. Anabaptism in Westphalia has primarily become known in connection with the radical Münsterite Anabaptism. Less known is the fact that after the end of the Münsterite movement in 1535 Anabaptism survived in various cities and communities in Westphalia. These Anabaptists, commonly known as "Mennisten" or "Tibben", had very little or nothing in common with the radical Münsterites. At the time of the Reformation Westphalia had three bishoprics, Münster, Minden, and Paderborn, and the abbeys Korvey and Herford, which were religious territories subject directly to the emperor. Secular entities were Cleves and the Duchy of Westphalia. Many of the cities of the province enjoyed great freedom. These territorial conditions determined to a large extent the outcome of the denominational lines of the province, in accordance with the principle cuius regio eius religio. In 1947 the province of North Rhine-Westphalia (Nordrhein-Westfalen) was formed.

The Lutheran reform movement reached Westphalia, particularly the eastern parts, in the early days of the Reformation. In the western part in places like Jülich and Cleves the Reformed influences became more noticeable. In the Duchy of Westphalia the Reformation came to a stop when Hermann von Wied, Bishop of Cologne, abdicated in 1547. Philipp of Hesse exerted considerable influence in some parts. In the city of Münster various forces paved the way for the Reformation, some coming from Luther, others from the Lower Rhine and the Netherlands until the city was converted into a radical Anabaptist "New Jerusalem" which was liquidated in 1535 by the Bishop of Münster, Franz von Waldeck. All Anabaptism, everywhere, even if it had nothing to do with the "New Jerusalem," had received a setback from which it never recuperated, particularly in Westphalia. Keller's three-volume work, Die Gegenreformation in Westfalen und am Niederrhein, is to a considerable extent a record of the heroic struggle for survival by peaceful Anabaptism in the province of Westphalia. The Reformed and the Lutheran churches were, of course, witnessing in a similar way. Yet in his presentation of Der Kampf um eine evangelische Kirche im Münsterland 1520-1802, Friedrich Brune finds the evangelical movement closely interwoven with Anabaptism, particularly in the beginning, and his book is therefore also to some extent a history of Anabaptism in the rural areas of Münster seen from a Lutheran point of view.

After "Münster"

In the city of Münster, Catholicism was fully restored after 1535, but Philipp of Hesse insisted that at least one or two evangelical ministers be permitted to preach. Anabaptists, of course, were not permitted in the city. Münster, however, had lost the political, intellectual, and religious liberties it had enjoyed under the guilds that were now forbidden. In the surrounding towns and communities of Ahlen, Warendorf, Dolmen, Coesfeld, Ahaus, Vreden, Bocholt, Borken, and Freckenhorst, not only Protestantism but also Anabaptist congregations survived at places for a century.

In Warendorf, where Anabaptism found entry in 1534, one of the Anabaptist preachers was Johann Klopreis. More than fifty persons were baptized here. The city council was sympathetic toward Anabaptism until Franz von Waldeck interfered. The monastery Freckenhorst near Warendorf, which became Protestant in 1532, was an Anabaptist stronghold. In Coesfeld Anabaptism was established in 1534. Some followers went to Münster. In Dülmen the evangelical movement and Anabaptism were started through the preaching of Bernhard Rothmann. Two ministers from Münster were invited to promote the preaching of the Gospel there but were stopped by the bishop. In Vreden there were "several sects" who met outside the city in the barns and groves and practiced "their unusual baptism" (Brune).

Bocholt also had special significance for the Anabaptists: a meeting of the surviving groups took place in 1536 in which David Joris seems to have been dominant. Adam Pastor, for a while a co-worker of Menno Simons, came from "Dorpen" in Westphalia, evidently the village of Dörpen on the Ems in the northern part in the bishopric of Münster. On Menno Simons' journey from East Friesland to Cologne in 1545 and also when he returned to Lübeck in 1546 he may have passed through Westphalia.

Cleves-Mark

The persistence of the Anabaptists in Cleves and Mark is verified by the edicts issued by Count Wilhelm to his officers. On 9 March 1560, he gave detailed instructions as to the techniques to be used to win them back to the church. On 10 June 1560, the circulation of Anabaptist books was forbidden. On 23 January 1565, he addressed the mayor and the city council of Soest demanding that they proclaim non-tolerance of the Anabaptists. On 28 July 1576, he again issued an edict against the Anabaptists of Cleves-Mark, and on 16 August 1576, another for the city of Soest. Again on 24 September 1580, he decreed "that Anabaptists, Calvinists, and other sects" should be forbidden and that their ministers should be imprisoned; strangers were to carry passports. On 1 October 1585, he again issued an edict against "Corner-baptists and Anabaptists, Sacramentists," and other sects, calling attention to the previously published edicts.

The third synod of Berg, 3 January 1590, states that Anabaptists were forbidden in the city of Elberfeld. On 25 February 1619, it was reported that the city of Sittard had a number of citizens who were Anabaptists, and on 9 April 1619, it was reported that "the Anabaptists are increasing" in the country of Löwenberg (the only place that has thus far been fully investigated). (Keller I, 90, 92, 119, 245, 247, 259; 11,75, 102; III, 253 f.)

Bishopric of Münster

The minutes of the Cathedral Chapter of Münster of 1596-97 deal extensively with the Anabaptists at such places as Wüllen, Borken, and Vreden. Special attention was to be paid to the "Tibben" or Anabaptists who were penetrating cities here and there.

The Anabaptists of Bocholt, it was reported to the council of Münster on 18 December 1599, had not left the city on the specified date. On 6 June 1607, the council of Münster asked the officers of Bocholt, Ahaus, and other places to expel the Anabaptists immediately. On 18 July 1607, the Anabaptists writing "to the Council of Münster" referred to themselves as "All fellow believers, commonly known as Mennisten." They declared that they had nothing in common with the Münsterites of 1533; everybody could testify that they were quiet citizens; for this reason they requested that the edicts against them be annulled. A similar petition was sent to the Elector Ernst on 18 August 1607, and also on 12 September 1607, by citizens of Vreden. The negotiations concerning the exile of the Anabaptists at Ahaus, Bocholt, Vreden, and Borken continued.

In an edict of 20 October 1611, Anabaptists of Horstmar, Borkelo, Bevergern, Kloppenburg, Dülmen, Werne, Wolbeck, Sassenberg, and Stromberg are mentioned. From that date until 19 June 1612, numerous reports were issued on the subject. Places like Freckenhorst and Harsewinkel still had Anabaptists. A list of Anabaptists at Vreden and Ahaus was submitted on 6, 20, and 22 June 1612. On 2 September 1614, it was reported that the Anabaptists who had been exiled from Borken, Vreden, Bocholt, and Ahaus had returned. Negotiations concerning the Borken Anabaptists continued through 24 October 1622.

In 1612 Warendorf, Freckenhorst, Harsewinkel, Beelen, Bocholt, Ahaus, Ottenstein, Wessum, Wüllen, Vreden, and other places still had some Anabaptists, particularly Vreden. Gradually, however, they had to leave these places, moving to Gronau, Hamm, Emmerich, Emden, Winterswijk, and Zutphen. However, during the official Catholic Church inspection of 1613-16 numerous Anabaptists were still found in various places. Borken still had six or seven members who met regularly. (Keller II, 334 ft, 345, 354, 389, 407 ff.; Ill, 398, 404 ff., 429 ff, 491 ff., 512, 527,535, 570 ff., 581 ff.)

The various records give impressive information on the number and the steadfastness of the Anabaptists in Westphalia. However, they reveal little regarding their basic beliefs and practices. There is no trace of revolutionary activities. Brune, a Lutheran author, speaks very highly of them in his study of the Lutheran church, designating them as pious, industrious, and reliable citizens, highly honored by their neighbors. In Warendorf even a Catholic priest, Boethorn, is said to have sympathized with the Anabaptists in the early 17th century.

Other Areas

The Martyrs' Mirror reports under the year 1601 that Johann von Stein, Count of Wittgenstein, Lord of Homburg, executed four Anabaptists, Hybert op der Straaten, his wife Trynken, Pieter ten Hove, and Lysken van Linschoten. At the beginning of the 18th century there was a small Mennonite church in Hamm, gravure of Mark, and at the end of the century there was a small Amish Mennonite church at Petershagen near Minden.

Later Period

To what an extent, if any, the membership of the Mennonite Church of Gronau is of old Westphalia Anabaptist stock is not known. In any event this is the oldest Mennonite church in Westphalia. It was organized 4 February 1888, in Gronau, 32 miles northwest of Münster, by about 20 Mennonite families living in Gronau and Ahaus, where a large Mennonite industrial center has since developed. After World War II a number of Mennonite refugees joined the congregation. It was also the gateway for thousands of others who went to Canada. After World War II numerous Mennonites from eastern Germany and some from Poland and Russia settled in Westphalia, and have organized churches in several places. The Bergisches Land congregation was organized in 1948 in Niederar-Ahe; it includes also the Sauerland area and has a baptized membership of 199. The elder of the church in the late 1950s was Fritz Marienfeld. The congregation at Espelkamp, organized in 1952, had its own meetinghouse and a baptized membership of 150 in the late 1950s.

Another congregation, the Mennonite Church of Westphalia, met at various places during the late 1950s, such as Osnabrück, Münster, Recklinghausen, Bielefeld, Brakel, and Detmold, and had a membership of 600.

Bibliography

Brune, Friedrich. Der Kampf um eine evangelische Kirche im Münsterland 1520-1802. Witten, 1953.

Crous, Ernst. "Auf Mennos Spuren am Niederrhein." Der Mennonite VIII (1955): 187.

Crous, Ernst. "Die rechtliche Lage der Krefelder Mennonitengemeinde im 17. u. 18. Jh.," Beitrage zur Gesch. rhein. Mennoniten. Weierhof. 1939: 40.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. IV, 498-502.

Keller, Ludwig. Die Gegenreformation in Westfalen und am Niederrhein, 3 vols. Leipzig, 1881-95.

Mennonitischer Gemeinde-Kalender (formerly Christlicher Gemeinde-Kalender) (1892-1958): 82-85.

Risler, W. "Mennoniten in Duisburg," Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter (May 1951).

Risler, W. "Tauter im bergischen Amt Lowenburg, Siebengebirge." Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter (1955).

Stuperich, Robert. Das Münsterische Täufertum. Münster, 1958.

"Westfalen." Die Religion in Geschichte and Gegenwart, 5 vols. 2. ed. Tübingen: Mohr, 1927-1932.

| Author(s) | Cornelius Krahn |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1959 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Krahn, Cornelius. "Westphalia (Germany)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1959. Web. 19 Jan 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Westphalia_(Germany)&oldid=135749.

APA style

Krahn, Cornelius. (1959). Westphalia (Germany). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 19 January 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Westphalia_(Germany)&oldid=135749.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 4, pp. 935-937. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.