Great Trek, 1943-1945

The Great Trek was the period from 1943 to 1945 when thousands of Mennonite refugees left the Soviet Union in an attempt to escape to the west. With its retreat westward after the capitulation at Stalingrad, the German army was ordered to take with it the remaining population of Soviet Germans, numbering approximately 350,000; this number included 35,000 Mennonites.

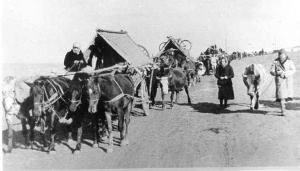

The initial phase of the Great Trek was relatively well organized and orderly. The first Mennonite settlement to evacuate was the Molotschna Mennonite settlement on 12 September 1943. As the front swept further westward, with the Red Army crossing the Dnieper River, the Chortitza Mennonite settlement was evacuated, some people traveling by railway, others joining the Molotschna wagon trains. By late October Zagradovka Mennonite settlement wagons also joined the long columns of evacuees. Eventually, with several stops along the way, the refugees reached the Warthegau area of Poland, where they remained in relative peace for almost a year.

The retreat of the German army from the Soviet Union began after its capitulation in Stalingrad in February 1943. That summer, the army was ordered to retreat, together with the Soviet German population of the area. On 9 and 10 September, the mayors of the Molotschna villages received word that they should obtain wagons for every family.

Over the next two days, a full-scale trek began from the Molotschna, with a caravan of wagons 10 kilometers long heading southwest. Refugees from the Chortiza Mennonite settlement joined in late September, and people from the Zagradovka Mennonite settlement at the end of October. Walking or riding in wagons or trains, the group arrived in the Warthegau area west of Warsaw in the middle of March 1944. There the refugees were distributed among many of the villages and farms in the area. They were offered Germany citizenship, which many accepted.

Of all the Mennonite migrations, the Great Trek was the most difficult and dangerous. Many people died of disease along the way or were killed by the Soviets or partisans. The Mennonites who went on this migration had already suffered many deprivations, and most of the able-bodied men had already been murdered or exiled. The families were therefore fragmented and consisted of a disproportionate number of women, old men, and children.

The Soviet advance continued, and by 17 and 18 January 1945 the front had reached Poland and East Prussia. The resulting evacuation, the "Flight," was a disorganized scramble for everyone to flee further westward. The Polish and Danzig Mennonites also joined the refugees, some trying to flee northward via the Baltic Sea. Some people fled on trains or wagons, but many left on foot. Many refugees were killed in the Soviet advance and the aircraft bombing and strafing of the refugee columns. Still, the survivors continued on, driven by their fear of what the Soviets could do to them.

When the surviving refugees did reach Germany, some had the misfortune of not having gone quite far enough. The Elbe River was the dividing line between east and west agreed on in Yalta, but no one communicated this to the refugees. Caught on the wrong side of the border, many people were sent back to the Soviet Union.

Even in the western zone, many people were caught and forcibly "repatriated" by the Soviets, often with the complicity of Allied forces. Of the 35,000 Mennonite refugees who started on the Trek, a total of about 12,000 escaped the Soviets and stayed in the western zone, while about 23,000 were captured and transported back to the Soviet Union, often to the far reaches of Siberia rather than to their homes. The 12,000 Mennonites who managed to escape the Soviets stayed in various areas in Germany, some in refugee camps. After long periods of waiting and many negotiations, approximately 6,000 refugees immigrated to Canada, and the other 6,000 moved to Paraguay, Uruguay, and Argentina.

The refugees who joined the Great Trek endured many hardships and struggles along the way, but for the ones who managed to escape to the west, it was a chance for a new life.

Bibliography

Dyck, Peter and Elfrieda Dyck. Up from the Rubble. Scottdale and Waterloo: Herald Press, 1991: 87-99.

Epp, Frank. Mennonite Exodus. Altona: Canadian Mennonite Relief and Immigration Council, 1962: 351-390.

Epp, Marlene. "Moving Forward, Looking Backward: The ‘Great Trek’ from the Soviet Union." Journal of Mennonite Studies (1998): 59-75.

Huebert, H. T. Events and People: Events in Russian Mennonite History and the PeopleThat Made Them Happen. Winnipeg: Springfield Publishers, 1999.

Huebert, H. T. Hierschau: An Example of Russian Mennonite Life. Winnipeg: Springfield Publishers,1986: 329-335.

Huebert, H. T. and William Schroeder. Mennonite Historical Atlas. Winnipeg: Springfield Publishers, 1990.

| Author(s) | Helmut T. Huebert |

|---|---|

| Susan Huebert | |

| Date Published | April 2009 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Huebert, Helmut T. and Susan Huebert. "Great Trek, 1943-1945." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. April 2009. Web. 12 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Great_Trek,_1943-1945&oldid=155816.

APA style

Huebert, Helmut T. and Susan Huebert. (April 2009). Great Trek, 1943-1945. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 12 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Great_Trek,_1943-1945&oldid=155816.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.