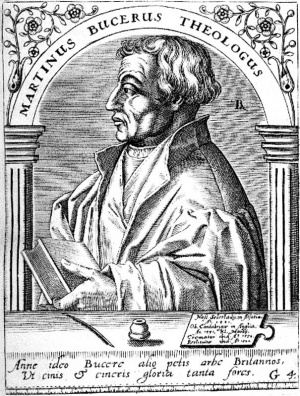

Bucer, Martin (1491-1551)

Martin Bucer (Butzer), the noted Strasbourg reformer, b. 10 November 1491 at Schlettstadt in Alsace, d. 28 February 1551 at Cambridge in England. At the age of 15 he entered the Dominican monastery as a student; in 1517 he matriculated at the university of Heidelberg, where he became acquainted with Luther and opened a correspondence with him. In 1520 he left the monastery cell and after a temporary stay in Speyer he found shelter on the Ebernburg of Franz von Sickingen. In 1521 he became chaplain at the court of the Elector Palatine Frederick, whom he followed to Worms and Nürnberg; in 1522, on the advice of his friend Ulrich von Hütten, he accepted the pastorate of Landstuhl in the Palatinate, the residence of Franz von Sickingen. Here he married a former nun. But in the same year because of the disturbances of war brought upon the town by the siege of the fortress of Sickingen by the Elector of Treves he was compelled to flee. He went to Weissenburg in Alsace and there founded a Lutheran congregation. In April 1523 he went to Strasbourg, where he worked with Wolfgang Capito, Caspar Hedio, and Matthias Zell, surpassing them all, an extraordinarily successful reformer. When the city council introduced the Interim in 1549 he emigrated to England, where he was received with great honor. After a brief but outstanding service on the faculty of Cambridge University he died.

Bucer's reformatory work was of wide significance. His influence extended throughout South Germany. Everywhere he strove zealously to bring about the unification of Protestants and to arbitrate between disputing parties. His warm love for the Protestant Church, his clear view, and his conciliatory attitude facilitated his role as intermediator.

He was particularly successful in dealing with the Anabaptists. He rejected the principle of the use of force and compulsion and tried to win them by means of private conversations and public persuasion at cross-examinations and disputations. His learning, his deep knowledge of the Scriptures, his judgment, his cleverness and ready wit stood him in good stead. Very wisely he always stressed the common, unifying points and toned down the divisive points. He was also very quick to detect his opponent's weakness and use it to his own end. Thus he succeeded in persuading many Anabaptists to return to the Reformed Church. When he could not accomplish it with words he called on the government to imprison or expel the Anabaptist; this happened in Strasbourg with increasing frequency; but he never sanctioned the death penalty. On 16 October 1532, Bucer and some of the preachers requested that the council order a disputation with the Anabaptists, of course only for the purpose of being able the better to suppress them after the hearing on pretended grounds. In 1533 Bucer published a Latin broadside in justification of infant baptism (What Is to Be Held of Infant Baptism According to the Holy Scriptures), but accomplished little thereby. The council was probably influenced by Capito's opposition to persecution. Capito's views were definitely expressed in a letter he wrote 17 April 1533 to the Zwinglian preacher Mäuschen (Musculus) in Augsburg, where he says: "Bucer is working for a government order to retain infant baptism. I do not want to stand in his way, but he must leave me out of the game, for I know well that the supports of infant baptism cannot be proved" (Thudichum). [Contrary to Neff's idea, Hege held the view that Bucer was of the opinion that the Anabaptists were deserving of death.] On 17 December 1546 he wrote to Philip IV of Hanau-Lichtenberg, that although on the basis of divine law the Anabaptists were deserving of death, this punishment should not be inflicted at the present time, because it was not being used against the vices of the Papists and the disregard of the Epicureans for religion (Hoffmann). Led by his experiences in combating the Anabaptists Bucer became the founder of confirmation.

Like Zwingli, Bucer also was at first very near the Anabaptist position in the matter of baptism. In December 1524 he wrote to Luther in the name of his co-preachers, "Baptism is an external matter. Baptizing those who have been taught to confess Christ would probably be more Scriptural and would destroy the error of the danger to salvation of the unbaptized. But they wanted to conform to the general custom: if only a time could be set for the instruction of those whom we, as far as we can remember, have baptized." In his book on the reason for the innovations in the congregation in Strasbourg on 26 December 1524, he wrote, "Mere water baptism does not save. Where anyone wishes to postpone baptism and is able to do this without destroying love and harmony among those with whom he lives, we will not quarrel with him or condemn him. Let each be sure of his opinion." On 26 September 1527 he said in a letter to Zwingli, that infant baptism is indeed Scriptural, but he was willing, where it was custom to baptize adults, to tolerate it for the present. But when the Anabaptists continued to increase in numbers he considered it necessary for the sake of the church that the government order the baptism of infants. In 1534 he finally brought it about that the magistrate of Strasbourg issued this order.

Another aid to Bucer in his winning of Anabaptists was his attitude to church discipline. With great determination he insisted on having stricter discipline introduced. "We absolutely need," he wrote 20 February 1531, "a certain church discipline because of the imperfect; as it is we are without any order. Through this very fact the Anabaptists, these arch-heretics, win their way to the simpler hearts with their blasphemies. For we have scarcely a sign of the old church to show wherein we have the discipline and service of the brotherhood in view" (Gerbert, 157). But the council would not listen to him.

At the beginning of the Reformation Strasbourg was an asylum for those persecuted and suppressed for their faith. Almost all the leading South German Anabaptist preachers came here. Thus a thriving congregation arose here. The first of these leaders who came to Strasbourg was Balthasar Hubmaier. In the summer of 1525 he came to Strasbourg from Waldshut to publish his book, Von der christlichen Taufe der Gläubigen. In March 1526 Wilhelm Reublin appeared. The congregation grew. Among its adherents were Jörg Ziegler and Hans Wolf of Benfeld. Of the latter Bucer gave the testimony "that he always conducted himself as a good man" (Bucer to Zwingli, 17 May 1526). Later, to be sure, he had some most unpleasant experiences with him when he without moderation attacked the Strasbourg clergy. Bucer apparently did not meet the first-named leaders. Soon afterward he began his task of converting the Anabaptists.

Bucer was asked to assist at the cross-examination of Jakob Gross from Waldshut and four other Anabaptists arrested in Strasbourg on 9 August 1526. The questions of infant baptism, government, and other points were to be discussed. Bucer did not consent to the first point, probably at that time not feeling able to prove it from Scripture. When Jakob Gross confessed that he had been expelled from Waldshut because he had not obeyed the order of the government to take up arms against the peasants in Zell, Bucer asked whether it is permissible to refuse to obey the government. Gross replied, that as far as he was concerned he would render obedience to the government, but that he would refuse to kill anyone, because it was not commanded by God. Then Bucer asked the catchy question whether he would call the government, which of course bears the sword, Christian. When Gross noticed that Bucer was about to entangle him in his own words he replied cautiously and evasively that he would leave the judgment to God; he acknowledged that the sword was given and commanded to temporal government to punish the wicked and edify the good. In general Gross did not seem favorably impressed by Bucer when he complained that "Bucer had commended him to the devil" (Cornelius, II, 268).

In the fall of 1526 Ludwig Haetzer came to Strasbourg and was hospitably received in Capito's home. Possibly early in November Hans Denck arrived. Michaei Sattler was also in the city at that time. It is very interesting to note the difference in the attitude of the reformers toward them. Sattler was most graciously and even fraternally received. But Haetzer and especially Denck were most violently opposed. In their booklet, Getreue Warnung der Prediger des Evangelii zu Strassburg über die Artikel, so Jakob Kautz, Prediger zu Worms kürzlich hat ausgehen lassen, die Frucht der Schrift und Gottes Worts, die Kindertaufe und Erlösung unseres Herrn samt anderem, darin Hans Denk, und andere Wiedertäufer schweren Irrtum erregen, betreffend, I. Joh. 4, 1, of 2 July 1527, prepared chiefly by Bucer, Michael Sattler is called "a dear friend of God," "a martyr of Christ," although he is a "leader of the Anabaptists." And in the touchingly beautiful letter of farewell written by Sattler to "his beloved brethren in God, Capito and Bucer" (spring of 1527), he says that he had conversed with them "in brotherly propriety and friendliness," and closes with the words, "The Lord be with all of you dear brethren in God" (Röhrich, 31).

Toward Hans Denck their attitude was different. When he had been there only a few weeks Bucer and Capito complained in letters to Zwingli and Blaurer that he had brought confusion to their churches. On 22 December 1526 a disputation was held between Bucer and Denck in the presence of 400 citizens. The council, not knowing of public participation in the disputation, had sent two delegates. Capito was also there, but did not take part. The discussion was based on Denck's book, Vom Gesetz Gottes; hence it must have dealt principally with the doctrines of reconciliation and salvation, though no details are known about the course of the debate. Evidently Bucer succeeded in convincing the councilors that it would be good for the city if Denck left. Two days later he was expelled from the city.

Bucer was probably aware of the superiority of the great Anabaptist leader, and feared that his influence would cause his congregation to crumble, hence his violent opposition. His verdict in the Getreuen Warnung on Denck was utterly unjust. He twisted Denck's statements, and gave them a false meaning. He called Denck's language so dark and confused that none of his adherents could understand Vom Gesetz Gottes; Denck used ambiguous phrases so that his statements could be twisted and turned to suit the required answer. This is of course a great exaggeration, even though it must be admitted that Denck's language is hard to understand. But Bucer also made the accusation that Denck "was unwilling to bind his spirit to the Scriptures" and "wanted to overthrow the Scriptures as of no avail." That this is not the case can be seen if one examines Denck's writings carefully and without prejudice.

Beyond this, Bucer declared, "Denck wished to make sin a vain delusion, i.e., nothing." Thus he misinterprets expressions in Denck's books as "Sin, as committed by man, is nothing against God," or "For sin is to be reckoned against God, and be it ever so great, God can and will and has overcome it." Bucer also went too far when in the detailed discussion of the last two statements of the seven theses of Kautz he called Denck's doctrine of the freedom of the will an obvious denial of salvation through Christ and asserted that he declared human nature, which is of course entirely corrupt, to be righteous. But he was altogether unreasonable in asserting, "Denck was unwilling to disapprove the deed committed in St. Gall, when one beheaded his brother." He evidently relied here on rumor. The fact that he credulously received it and made use of it shows clearly enough how incapable he was of judging the noble-minded Anabaptist leader.

Bucer's attitude to Martin Borrhaus was similar. Borrhaus had also come to Strasbourg in November 1526, and been received by Capito. Bucer celebrated him as a man of unusual greatness of spirit (Bucer's letter to Farel, 13 December 1526). But when Capito became more and more deeply influenced by Borrhaus and in warm words of recommendation wrote the foreword to his book, De operibus Dei, and finally in his commentary on Hosea openly advocated Anabaptist views, the friendship between the two reformers nearly came to a break. Bucer turned to Zwingli and Oecolampadius for help and urgently requested them to exert all their influence on changing Capito's mind. This was done. A complete break between Capito and Bucer was averted; the estrangement lasted until 1533. Bucer placed the blame on Borrhaus and heaped the bitterest reproaches upon him, calling him a man "completely ruined by Anabaptism," and warning his friends of him. He was obviously very unjust.

In his attitude toward the Anabaptists Bucer became increasingly severe. When he noticed that he accomplished little by persuasion and that the Anabaptist movement in the city continued to grow, he appealed to the council with his fellow preachers with the request that they undertake more energetic measures against the Anabaptists. As a result a severe mandate was issued on 27 July 1527, against the Anabaptists, commanding all the citizens, inhabitants, clergy, and laymen in city and country to guard against such erroneous, unscriptural misleading, to get rid of the Anabaptists or their adherents, and offer none of them shelter, food, drink, or concealment. The mandate was immediately put into effect. The Anabaptists wherever found were seized, tried, and in part expelled from the city. Many of the remaining took the oath of citizenship. On 8 February 1528, Bucer wrote to Ambrosius Blaurer that all the Anabaptists had sworn the oath, but he feared that they had done so merely to continue to live in the city and could do more harm than before.

Early in August 1528 the council managed to break up an Anabaptist meeting at "the Plow." On 15 August the prisoners were tried in the presence of Bucer and Capito. In his commentary on Zephaniah, Bucer stated that one of the Anabaptists asserted on the basis of 1 John 3: 8-9, that no one who sinned could be a Christian and denied that he sinned. He of course felt temptations to sin, but the Holy Spirit suppressed them. When Bucer called his attention to the petition in the Lord's Prayer, "forgive us our debts," the other was embarrassed; he observed that the prayer had been given to the apostles before they received the Holy Spirit; after Pentecost they no longer prayed thus. He could not do so either, for he was not aware of any sin. Judging from this, these Anabaptists belonged to the fanatical wing. Several days later they were tried again. The reformers had hopes of being able to lead them to better understanding. They succeeded in only one case. The others persevered in their conviction.

In the middle of August 1528 another meeting of Anabaptists, held in the house "aan de Kade," was surprised. This time the Anabaptist leaders Kautz, Reublin, and Pilgram Marpeck were among them, as well as prominent citizens like Friedolin Meyer and Lux Hackfurt. Bucer, who had already talked to Kautz in June 1528 (Bucer to Zwingli, 24 June 1528), wanted a public disputation with them; he said from the pulpit that he "was not afraid of the pride and fluency"; but the council decided that Kautz and Reublin should be privately instructed from the Scriptures, but agreed that it might be done in writing. Bucer and the other city preachers turned in a refutation of Anabaptist views; and Kautz and Reublin sent in a frank statement of their faith, especially on baptism (Röhrich, 44). Then the preachers were ordered to deal with them orally, but without result; for the Anabaptists wished to defend their faith before the congregation or at least before the magistracy. Thereupon the preachers again requested the council to permit a public disputation, "because these two are among the most important of those called Anabaptists, and have respect not alone here but also as far as the sect is scattered, and many adhere to them." But the council continued to refuse it. Then Kautz and Reublin compiled a detailed statement of their faith, which is unfortunately lost; only its rebuttal by the city preachers is preserved (City Archives at Strasbourg, AA Ladula, No. 399 (9); Hulshof, note, p. 89).

In this document (Hulshof, 93 ff.) Bucer sets forth: the fact that "many pious persons are unfortunately laden with the Anabaptist error, but otherwise conduct themselves well and do not seek division" is not so serious "if one baptizes only the aged; unity should be preserved with these in all charity; for no one on earth is without error and mistakes; but there is the poison, where separation, division, and contempt for true Christians is found, with which unfortunately a large part of the Anabaptists is laden."

Bucer's first concern was the preservation of the unity of the church. For this he struggled and labored. All his wrath was aroused by the separation of the Anabaptists from the church protected by the authority of the state, and their establishing their own brotherhood; this angered him to the point of boundless resistance, even to spreading false accusations. About two weeks before Easter in 1529 he together with Hedio and Zell sent a report to the council (Cornelius II, 274), expressing the suspicion that "some intend to make all things common property and compel everyone to accept their faith by means of the sword; besides they act contrary to Scripture with regard to marriage." In consequence the council had some of the outstanding prisoners tortured; but "none would confess that they had the women in common or were planning any revolt or anything of the sort."

Bucer had a "grim pleasure" in these tortures and other severe measures. In July 1529 he wrote to Zwingli, "The ruthlessness of the Anabaptists has compelled the council to proceed more severely against them. Then Satan fell miserably. They, the unyielding, were quite softened, partly by banishment and partly by confinement in a dungeon. Those who were made quite wild by the most friendly Scriptural opinions soon changed their conduct; the bailiff had only to say ‘he is expelled, or throw him into a deeper dungeon.'"

The growth of the Anabaptists in the city caused Bucer great concern. In a letter of 11 December 1531 he inquired of Blaurer how he managed to win so many Anabaptists over. The failure of his efforts made his attitude toward them more and more rude and biased. This attitude is reflected in his treatment of Pilgram Marpeck. He described the character of this highly gifted and estimable Anabaptist leader at great length in his letters to Blaurer and Blaurer's sister Margarethe, who was deeply interested in Marpeck's personality. He could not close his mind to the excellencies and virtues of this man. "He is of fine and irreproachable conduct;—but he has cleverly laid aside the coarser vices; the spiritual ones affect him so much the more grossly." He resented most of all Marpeck's refusal to yield his separation from the church. "Pilgram will not desist from his baptism and from persuading the people that swearing and bearing arms are wrong; therefore I fear that he will be expelled from the city. For this reason be on your guard if he comes to you, not to be deceived by appearances" (Bucer to Margarethe Blaurer, 23 October 1531).

Bucer had three discussions with Pilgram Marpeck, twice before the entire magistracy, and once before a committee appointed by them, chiefly on the attitude to government and infant baptism, but without result. In the course of the last conversation, 18 January 1532, Bucer violently attacked his opponent with the words, "The fact that you Anabaptists, who make us out to be the enemies of Christ, thieves, and murderers of souls, do not expel and slay us, is only due to your lack of power. If you had it, I do not doubt that the spirit which keeps producing new ideas in you would soon teach you to kill all of us." Finally Bucer summarized all his accusations against Marpeck in a document which he presented to the council, in consequence of which Marpeck was expelled from Strasbourg. Before leaving the city the latter wrote a detailed defense of his faith, refuting Bucer's statement (published inMennonite Quarterly Review 12, 1938, 167-202), and wrote a letter of farewell to the magistracy, which "by its simple sincere tone says not a little for the character of the man" (Gerbert, 105; Röhrich, 57; Monatshefte der Comenius-Gesellschaft, 1896, 311).

We shall omit an account of Bucer's relations with Sebastian Franck and Caspar Schwenckfeld, who were close to the Anabaptist brotherhood, and mention his attitude toward Melchior Hoffman. He came to Strasbourg in June 1529 and at once joined the Anabaptists. On 30 June 1529, Bucer announced his arrival to Zwingli. Although Hoffman's two visits to Strasbourg were brief, his influence must have been extraordinary. There were fanatical aberrations. Wonderful "visions" and "revelations" were reported. Bucer was alarmed by "revolting and impious idolatries" he saw in the city, causing him sometimes to despair of the future of his church (letter to Blaurer, 18 March or 18 April 1532, Hulshof, 121, 249). He lamented it in a letter to the council in October 1532. In the spring of 1533 Hofmann made his third appearance in Strasbourg, and was captured a few weeks later, in May. According to a letter written by Bucer to Bishop Christian in Augsburg (Cornelius II, 355), Hoffman offered himself to the magistracy for arrest in order to fulfill a prophecy of a glorious conclusion of the mission entrusted to him by God.

On 3-14 June 1533 the great synod of the Strasbourg church was held. Sixteen articles of faith drawn up by Bucer were discussed and accepted. Only a small "Epicurean" party, including Otto Brunfels, made some objection (Bucer's letter to Blaurer of 3 February 1534). Nearly all of the 16 articles referred to the Anabaptists. Their doctrines are often explicitly attacked in footnotes.

Without mentioning the Anabaptists, they refuted their position on the incarnation, baptism, communion, and the relation to government. This is evidence of the profound influence of the Anabaptists on the Protestant church in Strasbourg (Hulshof, 139 ff.).

The second part of the synod was devoted to the public disputation with the "sect leaders." The disputation with Melchior Hoffman was held on 11-13 June. Bucer's booklet, Handlung inn dem öffentliches Gespräch in Strassburg jüngst in der öffentlichen Synode gehalten gegen M. Hofmann durch die Prediger daselbst 1533 (copy in Mennonite Historical Library (Goshen, IN)), gives an exact account. Hoffman also published an open letter entitled Ein Sendbrief an alle gottesfürchtigen Liebhaber der ewigen Wahrheit, in welchem angezeigt sind die Artikel des Melchior Hofmann, derhalber ihn die Lehrer zu Strassburg als einen Ketzer verdammt und im Gefängnis mit Trübsal, Qual, Spott und Schande gekrönt und besoldet haben. It is not as exhaustive as Bucer's pamphlet, which seeks to refute Hoffman's teachings in detail (zur Linden, 329-36; Hulshof, 145-48).

Bucer was intellectually greatly superior to Hoffman. Mockingly he advised the Anabaptist to stop preaching and stick to his trade. His superior bearing in this disputation enhanced his prestige and strengthened his position in the city, and he was celebrated far and wide as the successful combatant of the heretics. This reputation induced Philip of Hesse to summon him to convert the Anabaptists imprisoned in Marburg.

But before this Bucer still had to undergo a difficult struggle with the Anabaptists in Strasbourg, who were holding frequent, well-attended meetings, in which visiting Anabaptists participated. They had connections all the way to Moravia. Kilian Aurbacher, a preacher in the Austerlitz congregation, wrote a letter to Bucer in 1534, violently accusing him of causing the lords of Strasbourg, who had formerly received and shown pity for the believing brethren of the Lord Christ, who were in all the German lands exiled, expelled, martyred, and killed, now to take such a hard attitude. "Who gave you, I ask, power and authority to forbid the teaching of Christ to those who fear the Lord, serve Him, and sincerely desire to follow Him, and want to obey the government as far as is reasonable and proper, and live in all deference, meekness, patience, and charity toward all men. . . . You poor, wretched, blind preachers, where you preach you see to it that you are girt on one side with the sword of the Lord and on the other with the sword of the government; while you have this at your side you are happy and can well speak of faith; but when you lose it, all is over and you run away as has often happened. . . . You have driven the poor lambs of Christ out of their poor huts into the cold winter. Can you not understand and see how Christian your conduct is and what evangelical fruit it bears? Is this sheltering or showing mercy to the poor, wretched exiles? Is this being conformed to the Gospel of Christ and His apostles?" (Hulshof, 165f.) Bucer dealt repeatedly with imprisoned Anabaptists in the period following; one of these was Cornelius Polterman, who thought that Bucer had the right name, "for he snuffed the lights of the people of Strasbourg and their eternal welfare and salvation, so that they now grope along a wall like the blind at noon" (Cornelius II, 74-85). Bucer apparently induced only a few to repudiate their convictions, but in Hesse he was so much the more successful.

In August 1538 Philip of Hesse invited Bucer to Hesse. Bucer accepted in a letter dated 20 September. On 29 October he arrived in Marburg from Cassel, where he first consulted the Landgrave. The disputation with the imprisoned Anabaptists took place on the next two days. He was completely successful (Hochhut, 627-644). He conducted the discussions with admirable skill. He stressed the need for the ban according to Matthew 18, 1 Corinthians 5, and 2 Thessalonians 3. "Where there is no discipline and ban there can be no church." In sharp words he lashed at their usury which offended the Anabaptists. Earnestly he impressed upon them their error in condemning infant baptism; just as one does not refuse communion to women because they are not mentioned at its institution, children should not be denied baptism. The church is right in baptizing infants; it follows the baptismal command in Matthew 28, "baptizing them and teaching them." Obedience should be given the government in all things not opposed to God's Word; where this is not obviously the case, the subject should be obedient to the advice of the government and not set himself up as a judge of the government and its command. But if a subject knows that the government commands him to do an open wrong, he shall not, like Saul's guards, seek to kill the priests.

In this manner he won the Anabaptists over. On 9 December 1538 nine Anabaptist prisoners drew up a confession of faith which almost entirely abandoned their former position (Hochhut, 612-622). Bucer and the Protestant clergy expressed their pleasure in a verbose document (Hochhut, 622-626): "Even though they do not completely confess their wrong and do not seem to understand that they have committed serious sin in rebaptizing, they [the clergy] after all praise God for aiding them to return to the church, in which may He preserve and strengthen them and us."

The most important of these converts was Peter Tasch, "the acknowledged head of the Anabaptists in all Hesse, whose widely ramified connections extended to England" (Wappler, 78). The Landgrave and the preachers were elated by the success of the Alsatian reformer. On his suggestion Tasch was used to convert the Hessian Anabaptists. According to Bucer, Tasch led about 200 persons from their Anabaptist views. Tasch and Eysenburg, also a former Anabaptist, were called to Strasbourg, probably in the hope that they might induce Melchior Hoffman to renounce his faith. Their conversation on 5 May 1539 with the Anabaptist leader, who was greatly weakened by his chains, lasted six hours; this was repeated five hours on four successive days. But they did not succeed, nor did the other Strasbourg reformers, in moving him.

After this nothing more is heard of Bucer's efforts to convert the Anabaptists. A mightier took his place—Calvin. Bucer was in Switzerland during the synod of the Strasbourg church in 1539, which was first of all concerned with opposing the Anabaptists. Calvin was the spokesman. Was Bucer perhaps in a gentler mood toward the Anabaptists because of his success? On 17 March 1540 he appealed briefly to Philip for Melchior Rinck, who had been condemned to perpetual prison, with the result that Rinck was transferred "to mild arrest in a room built especially for the purpose."

Bucer introduced confirmation into the Protestant church. He had already expressed this idea in 1534 in his book Ad monasteriensis. It was first recommended for adoption in the Ziegenhainer Zuchtordnung, 1538, which was principally his work. Consideration for the Anabaptists induced him to introduce confirmation as a sort of substitute for baptism on confession of faith. Thus confirmation seems to be a concession to the Anabaptists (Mennonitische Blätter, 1912, 91; 34 ff.).

Bucer's attack on the Anabaptists in his commentary on the Gospels, which is reflected in its various editions, is a chapter in itself. It is fully presented by A. Lang in Der Evangelienlkommentar Martin Butzers und die Grundzüge seiner Theologie. He says (45), "Bucer is most considerate to the powerful opposing party of Anabaptists, who are in the consciousness of the people often considered holier than the reformers themselves. He relates personal contacts and conversations with the Anabaptists.—Doubtless Bucer's commentaries offer the historian many a line to illustrate the Anabaptist movement."

On the whole Bucer was a severe, but moderate opponent of the Anabaptists. Although he finally also believed that he could not get along without government measures of force in combating them, he nevertheless protected them from the bloodiest persecution. He never spoke in favor of the death penalty. As far as is known, it was never applied in Strasbourg against the Anabaptists.

Bibliography

Anrich, Gustav. Martin Bucer. Strassburg: Karl J. Trübner, 1914.

Baum, J. W. Capito und Butzer, Strassburgs Reformatoren. Elberfeld: R.L. Friderichs, 1860. Reprinted Nieuwkoop: B. de Graaf, 1967.

Bellardi, Werner. Die Geschichte der "Christlichen Gemeinschaft" in Strassburg (1546/1550) : der Versuch einer "zweiten Reformation" ; ein Beitrag zur Reformationsgeschichte Straßburgs mit zwei Beilagen. Leipzig: Heinsius, 1934.

Bornkamm, Heinrich. Martin Bucers Bedeutung für die europäische Reformationsgeschichte. Schriften des Vereins für Reformationsgeschichte ; Nr. 169. Gütersloh: C. Bertelsmann, 1952. Contains a complete list of works by and about Bucer.

Cornelius, Carl Adolf. Geschichte des Münsterischen Aufruhrs in drei Büchern. Leipzig: T.O. Weigel, 1855-1860: II.

Diehl, Wilhelm. "M. Butzers Bedeutung für das kirchliche Leben in Hessen." Schriften des Vereins für Reformations-Geschichte, No. 83. Leipzig, 1904.

Eells, Hastings. Martin Bucer. New Haven: Yale university Press ; London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1931.

Gerbert, Camill. Geschichte der strassburger Sectenbewegung zur Zeit der Reformation 1524-1534. Strassburg: J. H. Ed. Heitz (Heitz & Möndel), 1889.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe; Schneider, 1913-1967: v. I, 307-313.

Herzog, J. J. and Albert Hauck, Realencyclopedie für Protestantische Theologie and Kirche. 24 vols. 3. ed. Leipzig: J. H. Hinrichs, 1896-1913: v. III, 603 ff.

Hochhut, K. "Mitteilungen aus der protestantischen Sektengeschichte in der hessischen Kirche." Zeitschrift für historische Theologie (1858): 538-644.

Hoffmann, Heinrich. Reformation und Gewissensfreiheit. Giessen: Töpelmann, 1932: 23, 37.

Hulshof, Abram. Geschiedenis van de Doopsgezinden te Straatsburg van 1525 tot 1557. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: J. Clausen, 1905.

Krohn, Barthold Nicolaus. Geschichte der fanatischen und enthusiastischen Wiedertäufer vornehmlich in Niederdeutschland: Melchoir Hofmann und die Secte der Hofmannianer. Leipzig: B. C. Breitkopf, 1758.

Lang, August. "Butzer in England." Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte (1941): 230 f.

Lang, August. "M. Butzer’s last letter." Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte

Pauck, Wilhelm. The Heritage of the Reformation. Boston, 1950.

Paulus, Nikolaus. Die Strassburger Reformatoren und die Gewissensfreiheit. Strassburg: Agentur von B. Herder ; St. Louis, Mo.: Herder, 1895. Catholic

Röhrich, T. W. "Zur Geschichte der Strassburger Wiedertäufer in den Jahren 1527-1543." Zeitschrift für historische Theologie (1860): 1-120.

Schultz, Rudolf Martin Butzers Anschauung von der christlichen Oberkeit dargestellt im Rahmen der reformatorischen Staats- und Kirchentheorien. Doct. diss. Freiburg, 1932.

Wappler, Paul. Die Stellung Kursachsens und des Landgrafen Philipp von Hessen zur Täuferbewegung. Münster: Aschendorff, 1910.

Wolf, Gustav. Quellenkunde der deutschen Reformationsgeschichte. Gotha: F. A. Perthes a.-g., 1915-23: II, Part 2.

Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte (1885): 473.

Zur Linden, Friedrich Otto. Melchior Hofmann: ein Prophet der Wiedertäufer: mit neun Beilagen Haarlem: De Erven F. Bohn, 1885.

| Author(s) | Christian Neff |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1953 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Neff, Christian. "Bucer, Martin (1491-1551)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1953. Web. 12 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Bucer,_Martin_(1491-1551)&oldid=85813.

APA style

Neff, Christian. (1953). Bucer, Martin (1491-1551). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 12 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Bucer,_Martin_(1491-1551)&oldid=85813.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, pp. 455-460. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.