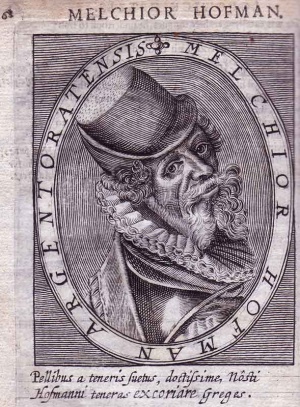

Hoffman, Melchior (ca. 1495-1544?)

Scan provided by the Mennonite Archives of Ontario.

1956 Article

Melchior Hoffman (Hofmann, Hofman), the noted early Anabaptist leader, was born about 1495 at Schwäbisch-Hall. He received a good elementary education and learned the furrier's trade. He was early interested in religious literature, especially the writings of the mystics, Tauler, Deutsche Theologie, etc. He also acquired a thorough knowledge of the Bible. The writings of Martin Luther moved him deeply and he became Luther's zealous follower.

In 1523 business took him to Livland; here he was soon drawn into the religious movement of the Reformation. In the shortage of Protestant preachers, Hoffman entered this service and preached at Wolmar until persecution caused his imprisonment and expulsion from the country. Nevertheless his influence here must have been lasting, for even from Sweden he wrote admonitions to his Wolmar friends. In the fall of 1524 he came to Dorpat where he preached against the use of images. This led to a fateful wave of iconoclasm (10 January 1525), in which he, however, did not participate (Leendertz, 26). The populace successfully opposed his arrest by the church authorities; this constituted a victory for the Protestant cause.

In the new state of affairs the city council was doubtful about permitting the furrier to continue his preaching, and demanded an approval of his doctrine by recognized theological authorities. He therefore betook himself to Riga where the Protestant preachers Knöpken and Tegetmeier gave him this approval. Hoffman then went on to Wittenberg to get Luther's confirmation of his preaching. He arrived there about the middle of June and was joyfully received by Luther. Luther and Bugenhagen together wrote to the churches in Livland Ein christlich Vermahnung von äusserlichem Gottesdienst und Eintracht an die in Liefland, durch Martinum Luther und Andere (Wittenberg, 1525), to which Hoffman added a letter of 22 June (Krohn, 51-57) with the title, "Jhesus Der christlichen gemey zu Derpten ynn Lieflandt wunschet Melchior Hoffman gnad und fride, sterkung des Glaubens von Gott dem vater und dem Hern Jhesu Christo. Amen." This is Hoffman's earliest known writing. In addition, to a strong emphasis on justification alone through faith, the author already stresses the sanctification of life, which must be shown in all the fruits of the Spirit. He opposes the "fanatical spirits" who make themselves illegal executors of God's judgment; for "he who takes the sword shall perish by the sword." In this letter Hoffman's allegorical interpretation of the Bible and his chiliastic ideas are already evident. (Leendertz considers it unlikely that Hoffman met Schwenckfeld and Andreas Karlstadt in Wittenberg, but believes that he became acquainted with Karlstadt's writings here, pp. 41 ff.)

With Luther's written recommendation Hoffman returned to Dorpat in the late summer of 1525. His self-esteem had risen considerably, making his relations with the Lutheran clergy intolerable. They refused to recognize Luther's authorization, whereas Hoffman accused them of self seeking and of denying by their life the faith they preached. He declared that they did not have the divine call to preach, and that they were incapable of understanding the simple word of Scripture. He considered himself a prophet called to testify to the imminence of the final judgment by a stirring cry for repentance. Again and again he referred to Enoch and Elijah, the two witnesses of Christ's return and with increasing strength the idea possessed him that he was one or the other of the two. His most violent opponent was Tegetmeier, who published a polemic against him, making his position in Dorpat untenable and compelling him to leave the town again.

From Dorpat, Hoffman went to Reval in the fall of 1525. Here the Reformation had been introduced and the preaching offices were filled. "There I was made the servant of the sick," he writes. Unselfishly he devoted himself to the service of the church. For his preaching service in Dorpat he accepted no salary, but supported himself with his own labor (Leendertz, 14 and 53). But before long the Lutheran clergy in Reval accused him of heresy because in addition to faith he insisted on the necessity of holy living. His views on communion also differed from Lutheran doctrine. On the other hand, the absence of the fruits of faith in the Lutheran brotherhood raised doubts in Hoffman's mind as to whether it was the true Christian church; the idea of separation from it seems to have occurred to him at this time. He was expelled from Livland.

The prospect of success in Hoffman's trade took him to Sweden. The German Lutheran Church in Stockholm conferred the office of preaching upon him early in 1526. He married and a son was born to him there. He perhaps hoped that his position would be permanent. But King Gustav Vasa, fearing that the stormy nature of the preacher might embarrass the young government, requested his resignation (letter of 13 January 1527), and Hoffman was compelled to move on.

Melchior Hoffman wrote three booklets in Stockholm. The one on the judgment day is lost. The second has the title, An de gelöfigen vorsambling inn Liflant ein korte formaninghe, van Melcher Hoffman sich tho wachten vor falscher lere de sich nu ertzeighen unde inrithen under der sthemme götliker worde (1526). The first part of this booklet is to reveal the "Hiddenness of God," and deals largely with the declaration of the last things, while the second practical part is an argument with his opponents in Livland. The other book offers an exposition of Daniel 12: Das XII. Capitel des propheten Danielis ausgelegt, und das Evangelion des andern sondages, gefallendt inn Advent, und von den zeychenn des jüngsten gerichtes, auch vom sacrament, beicht und der absolution, eyn schöne unterweisung an die in Lieflandt und eyn yden christen nutzlich zu wissen (1526). This important book falls into six parts; the first contains a complete exposition of Daniel 12, verse by verse; the second explains the Gospel for the second Sunday of advent; the third demonstrates that laymen should also be preachers; the fourth deals with communion, the fifth with the confessional, and the sixth with the office of the keys. Of special interest for us is Hoffman's teaching on communion. For him communion is a memorial of the death of Christ and at the same time a celebration of closest union with Christ, which is the product of faith. Conspicuous is this early agreement with the Anabaptists in their rejection of all force in matters of faith and the oath. The end of the world is to occur in 1533.

From Sweden, Hoffman returned to Germany, temporarily to Lubeck. It is possible that his ruthless, passionate defense of the Reformation here drew upon him persecution by the city council. Only by hasty flight was he able to avoid a tragic death. Early in 1527, with his wife and child, he arrived in Holstein territory, which was at that time Danish. At first he was unable to establish himself here. In May he made a second trip to Wittenberg, visiting en route at Magdeburg, Luther's friend Nicolas Amsdorf. He evidently wrote Amsdorf of his intention to visit him, for Amsdorf inquired of Luther how to receive this "prophet" and was advised to give him a cold reception and to advise him to return to his trade. Amsdorf consequently rudely showed him the door. In Wittenberg Hoffman was also rejected. Bitterly disappointed he started back; at Magdeburg en route he was jailed and robbed. He placed the blame for this on Amsdorf who had published a violent polemic against him. In Hamburg his poverty compelled him to accept alms from the pastor Zegenhagen.

But when Hoffman arrived in Holstein, great success awaited him. Frederik I, the Danish king, was pleased by his sermons and had him given a position as preacher at the Nicolaikirche at Kiel along with the pastor Wilhelm Pravest. But he lacked the qualifications needed to conduct a quiet and orderly pastorate. He continued his allegorical exegesis of Scripture, finding in every detail of the, Ark of the Covenant profound, divine meaning. His favorite topic was "the last things." Without moderation he attacked the senators of Kiel, calling them rogues and thieves from the pulpit.

With his colleague Pravest, who was not of the highest character, his relations were never entirely friendly. Pravest wrote to Luther for advice on the attitude he should take, and received the reply that M. Hoffman, the furrier, should be silenced, for he was neither competent nor called to preach. When Pravest made dishonorable use of this letter, Luther rebuked him in a second letter and to a certain extent defended Hoffman. In a letter to the mayor of Kiel Luther also remarked that Hoffman's intentions were good, but that his acts were hasty.

But Luther's favorable opinion was of short duration. When Hoffman was engaged in his ink-campaign against Amsdorf, Luther wrote to Duke Christian of Denmark, expressing the wish that Hoffman refrain from preaching until he should be better informed. Even more fraught with disaster for Hoffman was his conflict with the Lutheran clergy of Holstein concerning the communion. The bitterness was so deep that the king agreed to proclaim a public disputation.

This disputation was held in the spring of 1529 at Flensburg. Karlstadt, invited by Hoffman to help him, was unable to do so, for Hoffman was unable to secure a safe conduct for him. A stately audience of 400, including the nobility and clergy, met in the church of the monastery of the Barefoot Friars. On the preceding day Hoffman had handed Luther's Vom Missbrauch der Messe to the duke, as support for his concept of communion. On the same evening the duke pleaded with him to yield; when this proved vain he threatened Hofmann with banishment. Hoffman replied that all the scholars of Christendom could not justly do him any harm; but even if God should permit violence to be done to him, they could take from him only his old robe of flesh, which Christ would replace with a new one at the judgment. The duke expressed some surprise that Hoffman would dare to speak so boldly to him, whereupon Hoffman replied, "If all the emperors, kings, princes, popes, bishops, and cardinals should be together in one place, nevertheless the truth shall and must be known to the glory of God; may my Lord and God grant me this." On the next morning, when the duke asked Hoffman about his adherents, he answered, "I know of no adherents; I stand alone in the Word of God, let each do likewise."

Duke Christian presided. Bugenhagen, who was to function as referee without participating in the debate, spoke the opening prayer while the audience kneeled. On Hoffman's side Jan van Campen, Jakob Hegge of Danzig, and Johann Barse spoke; then the disputation was closed. The next day the king presided as the verdict was read, which was solemnly proclaimed in the Franciscan monastery three days later: Melchior Hoffman and those of like opinion must leave their home towns within two days after arriving there, and leave Danish territory within three additional days. Hofmann complained that he had been expelled with wife and child, his house plundered, and an estate of 100 guilders in books and printed matter taken; "even his life was in danger, but God helped him" (Leendertz, 119-35).

From Holstein, Hoffman went to East Friesland. En route he met Karlstadt, and the two arrived there in late April or early May. At this time Count Enno II was about to reinstate Lutheranism in the place of the Reformed faith. Karlstadt opposed this plan with passion, agitating against Luther "from fortress to fortress, from parsonage to parsonage." Hoffman was probably staying quietly at the castle of Ulrich von Dornum (Leendertz, 141), engaged in writing his Dialogus on the Flensburg disputation. He was kindly accepted as a colleague by the Reformed preachers. He was, however, unable to oppose Enno's plans actively, for he again found himself in embarrassing circumstances and left the country in haste.

Hoffman now betook himself to Strasbourg, where he was received with open arms at the end of June 1529 as a champion of Zwingli's teaching on the communion (letter by Bucer to Zwingli, 30 July 1529). At first he kept very quiet, staying in the house of Andreas Kleiber and his wife Katharina Leid, a gifted woman, who joined the Anabaptist brotherhood in 1532. He published his account of the Flensburg disputation under the title: Dialogus und grüntliche berichtung gehaltener disputation im land zu Holstein underm künig von Denmarck vom hochwirdigen sacrament oder nachtmal des Herren. In gagenwärtigkeit kü. ma. sun hertzog Kersten sampt kü. räten, vilen corn adel und grosser versamlung der priesterschaft. Jetzt kurtzlich geschehen den andern donderstag nach ostern im Jar Christi als man zalt 1529. He made his first contacts with Caspar Schwenckfeld, without, however, accepting his ideas. He continued to go his rather solitary way and to construct his own peculiar allegorical-spiritualistic doctrine. The theologically trained reformers of Strasbourg, unimpressed, advised him to return to his furrier's craft and stick to it. But Melchior Hoffman was convinced that the Holy Spirit fully compensated for any lack of education; book learning was a hindrance rather than a help. He therefore devoted himself to the publication of several booklets, which appeared early in 1530:

- Weissagung auss Heiliger Götlicher geschrift. Von den trübsalen diser letsten zeit. Von der schweren Hand und straff Gottes über alles gottlos wesen. Von der zukunfpt des Türkischen Thirannen und seines gantzen anhangs: Wie er sein reiss thun und vollbringen wird unns zu einer straff und rudten, wie er durch Gottes gevalt sein niderlegung unnd straff empfahen wird . . . (1530);

- Prophezey oder weissagung uss warer heiliger götlicher schrift. Von allen wundern und zeichen bis zu der zukunft Christi Jesu unsers heilands an dem jüngsten tag und DEr welt end. Diese prophecey wird sich anfahen am end der weissagung (kürtzlich von mir aussgegangen in eime andern büchlin von der schweren straf Gottes über alles gotloss wesen durch den Türkischen tirannen (1530);

- Auslegung der heimlichen Offenbarung Joannis des heyligen Apostels unnd Evangelisten (1530).

This last pamphlet was printed in Strasbourg by Balthassar Beck. (He was an Anabaptist according to zur Linden, p. 191, note 1, and was sentenced to prison for printing Hoffman's works without permission.) One of Hoffman's most significant works, this pamphlet had an especially disastrous effect through its glowing description of the return of the Lord. It was dedicated to the king of Denmark. The title page vignette is interesting, representing, as it does, Christ as judge of the world, with Elijah and Enoch as witnesses, and the sun-clad woman riding on the dragon (Revelation 12). In this book Hoffman divides church history into three periods, the first from apostolic times to the reign of the popes, the second the period of the unlimited power of the popes, and the third, already prepared by Hus, beginning with the Reformation, in which the pope is deprived of all power, and the office of the letter is turned into spirit. Then the two witnesses of the last day appear. To destroy them the adherents of the letter will combine with the papists; the two witnesses will suffer death, and the spiritual Jerusalem will be destroyed by the Turks. Prostration will last three and one-half years. Finally Christ will appear, hold judgment, and renew heaven and earth.

Meanwhile Hoffman had made contacts with the Anabaptist movement, and found what he was seeking. Their earnest piety, their simple Biblical faith, their religious mind, open to mystical and chiliastic ideas, attracted him. He became interested in Lienhard and Ursula Jost of Strasbourg, both of whom boasted of visions and revelations. He published their collected visions in two books; the first of these has the title, Prophetische Gesicht unn offenbarung, der göttlichen würkung zu diser letzten zeit, die . . . einer gottes liebhaberin durch den heiligen Geist geoffenbart seind. . .(1530). The other, proclaiming the prophecies of Lienhard Jost, has been lost. In spite of their confused ideas, these two books made a deep impression even in Holland (Hulshof, 118).

Hoffman had not actually joined the Anabaptists, when he took the unheard-of step of presenting a petition to the council (April 1530) demanding that a church be assigned to the Anabaptists. He demanded not only toleration for them, but also equal rights with the state church. He was obviously moved to this step by his warm sympathy for the suppressed brotherhood.

In 1530 Hoffman took the formal step of joining the Anabaptist brotherhood by baptism. But his residence in Strasbourg was of short duration. It is not likely that he became closely associated with Kautz and Reublin, who were living there at the time, for they were greatly superior to him in theological training. Nor was he the equal of Pilgram Marpeck. In clearness of spirit and depth of understanding of the Scriptures, Marpeck far outranked Hoffman. The city council issued an order of arrest against Hoffman because of his petition and on account of lesé-majesté in his exposition of the Revelation; he left the city hastily on 23 April 1530.

Hoffman now betook himself to East Friesland again, arriving there in May 1530. Luther, hearing of it, sent a letter warning the authorities in very sharp terms: Hoffman had long since been committed to Satan, and was filled solely with fanatical speculations, for the sake of which he let the cause of Christ perish. In June 1530 Hoffman appeared in Emden as a preacher. He gathered the elements dissatisfied with the established churches ("simple souls and the quiet in the land," Leendertz, 217) and through his eloquence acquired a large following. He can be considered the founder of the Anabaptist congregation at Emden, which is still in existence. In the city church of Emden, which the clergy had evidently given him, he is said to have baptized 300 persons. This created a great stir, and the council compelled Hoffman to leave the city. Hoffman left Jan Volkertszoon (Trijpmaker) in charge as preacher.

Hoffman now turned again to Strasbourg, impelled by worry concerning his wife and child (as zur Linden assumes). Along his route up the Rhine he won adherents for the new Bundesgemeinde. This term appears first in his most important and best work, the Ordonnanz Gottes, in which he presents his Anabaptist point of view for the first time. The title of this booklet is Die Ordonnantie Godts, De welche hy, door zijnen Soone Christum Jesum, inghestelt ende bevesticht heevt, op die waerachtighe Discipulen des eewigen woort Godts (1530). The term "ordinance of God" means to him Christ's baptismal command, Matthew 28:19. In opposition to justification he stresses sanctification, the "imitation of the life of Christ." As Jesus was tempted in the wilderness after His baptism, so all those who "in the end-times" are entrusted to Him in baptism by His true apostles, should follow Him in being led to the spiritual wilderness there to prove their steadfastness in the face of temptations. Here they must spend "forty days and forty nights in spiritual fasting"; not until they are complete in the favor, spirit, and will of Jesus Christ, and have fought to the end and have conquered, and in all the tests have remained faithful and unblamable, "is their justification perfected." Baptism, which should be the symbol of the covenant with God and the Lord Jesus Christ, shall be administered only to adults who can understand the Lord's teaching. But minor children, lifeless bells, churches, or altars shall not receive baptism; for not a single letter of the Old or New Testament can prove that infant baptism is commanded by God or was practiced by the apostles. After the presentation of his concept of communion, as it differed from that of Luther and Zwingli, he discusses the strict requirement of church discipline (BRN V, 127-170).

This time Hoffman remained in complete concealment in Strasbourg. The government was not aware of his presence there. He left the city with his family before the end of 1530.

In the course of 1531 he visited Holland; he stayed some time in Amsterdam, where he is said to have baptized 50 persons, and could move about unmolested. Though there is no information, he may also have visited other towns of Holland. Soon after his departure from Amsterdam conditions became much less favorable for Anabaptism. Volkertszoon and eight other followers of Hoffman (later called Melchiorites) were beheaded in The Hague on 5 December 1531. Nevertheless the brotherhood persisted, at first, of course, very quietly. Melchior Hoffman now decided to postpone baptism for two years and confine himself to preaching and admonishing; the construction of the Old Testament temple had also suffered an interruption of two years on account of resistance by the Samaritans (Ezra 4:24).

This order of delay Hoffman issued from Strasbourg; whither he had gone the third time in 1531. In this Strasbourg period he wrote a series of booklets:

- Verclaringe van den gevangenen ende vrien wil des menschen, wat ooc die waerachtige gehoorsaemheyt des gheloofs ende warachtighen eeuwighen Evangelions sy . . . (BRN V, 171-98). He takes a different position here from that in his exposition of Daniel 7 (1526), and skillfully blends Luther's idea with Denck's, taking a position between them. (Details in Leendertz, 239 ff.)

- Warhafftige erklerung aus heyliger Biblischer schrifft, das der Satan, Todt, Hell, Sünd, un dy ewige verdamnus im ursprung nit auss gott, sunder auss eygenem, will erwachsen sei . . . .

- Das freudenriche zeucknus vam worren friderichen ewigen evangelion (Revelation 14), welchs da ist ein kraft gottes, die da sallig macht alle die daran glauben, Romans 1, welchem worren und ewigen evangelion itzt zu disser letzten zeit so vil dausend ketzerischer irriger lugenhaftiger zeucknas gegenstandt. Nim war die postbotten seint draussen und schreien und die fridtbotten wynen bitterlich . . . (zur Linden reprints this pamphlet in his appendix, 429-432). Here is found the passage where Hofmann recognizes nobody as a preacher of the truth: "Alas, what a terrible time is this, that I do not yet see a true evangelist, nor know any writer among all the German people who witnesses to the true faith and the everlasting Gospel."

- Von der wahren hochprächtlichen einigen Maijestat Gottes, und von der wahrhaftigen Menschwerdung des Weigen worts und Sohns des allerhögsten, ein kurzes Zeugnis. Selig bistu Simon Jonas Sohn, dann Fleisch und Bluth hat dir das nicht offenbahrt, sondern mein Vatter im Himmel . . . . In this booklet Hoffman teaches the Triune God; he can therefore not be reckoned among the anti-Trinitarians, as Trechsel states in his Antitrinitarier (I, 34). He did, however, maintain that prayers should not be addressed especially to Christ or the Holy Spirit, but only to God (Leendertz, 142).

A new order of arrest by the city council again compelled Hoffman to leave the city. Whither he went is not definitely known. He traveled through Hesse, where Landgrave Philipp of Hesse heard him preach. He also stayed in the Netherlands in 1532, at least at Leeuwarden, the capital of the province of Friesland, where he had a number of adherents, including Obbe Philips.

In addition this man of inexhaustible energy had time for writing. He now published his exposition of the Epistle to the Romans: Die eedele hoghe enn trostlike sendebrief, den die heylige Apostel Paulus to den Romeren gescreven heeft, verclaert enn gans vlitich mit ernste van woort to woorde wtgelecht Tot eener costeliker nutticheyt enn troost alien godt-vruchtigen liefhebebbers er eewighen onentliken waerheyt . . . (1533). In this book, particularly in chapter XIII, Melchior Hoffman reveals himself as an advocate of quiet Anabaptism. He rejects the bearing of arms, and definitely demands unconditional obedience to the government for God's sake. The book concludes with these words: "By the mercies of God it is a small matter to me at this time to become a sacrifice to the All-High when God's work is completed through Christ. My rebukes and accusations are not made in fleshly envy and hate. God is my witness, that in .the depths of my heart I hate nobody. And if it were God's will that all be united in the truth, I would gladly serve them day and night as the lowliest servant; for their blindness grieves my heart, and day and night I sigh in my heart about it. In so far as any preacher is in the right I stand by him; but in the wrong no support does any good eternally; much rather would I lose my life a thousand times."

This willingness to die Hoffman was soon to prove in prison. His thoughts were centered on the imminent end of the world. He was firmly convinced that he was called to take a part as Elijah in the return of Christ. He was confirmed in this idea by the prophecy of an old Frisian Anabaptist that he would lie in prison half a year, and would then at the head of his adherents lead Anabaptism to victory over all the world.

In an exalted mood he entered upon his trip to Strasbourg. In the spring of 1533 he arrived there. Now he no longer remained in concealment. To be sure, he avoided appearing in public meetings, and he tried to avert the suspicion that he was fomenting insurrection; but in the house of the goldsmith Valtin Duft where he was staying his adherents streamed together. The city council maintained silence, and tolerated this activity. For two months he was unmolested; then he himself approached the council as if to have himself arrested. In May 1533 he sent a letter to the council, with a booklet, Vom Schwert, which has been lost, explaining that the kingdom of Christ would begin in Strasbourg, but it would be preceded by a terrible slaughter of (unbelieving) men; he awaited the fulfillment of these events here, and until that time would go about with bare head and bare feet, taking only bread and water.

The council met the prophet's desire, and in May 1533 had him arrested. Melchior Hoffman rejoiced. Now the awaited great time was at hand. Upon his imprisonment he thanked God (zur Linden, 322). Now his arrest was truly a mistake and a grave injustice, for insurrection and revolt were not to be feared from Melchior Hoffman. On the contrary, if anyone could have done so, he would have been able to direct the entire movement in Holland and Münster in peaceful paths.

The books Hoffman wrote during this time had in part a fantastic religious character:

- Der Leuchter des alten Testaments ussgelegt, welcher im heyligen stund der hütten Mose mit seinen siben lampen, blumen, knöpffen. . . . Und alles das such reicht uff die siben versamling des nuewen Testaments.

- The book on baptism: Erklerung des waren und hohen bunds des allerhöchsten has been lost. It was presented to the Strasbourg synod in 1533.

- Wahrhaftige Zeucknus gegen die Nachttoechter und Sternen das der Gott Mensch Jhesus cristus am Kreuzs und im Grab nit ein angnomen Fleisch und Blut aus Maria sey, sunder allein das vaure und ewige wortt und der unendliche Sun des Allerhöchsten.

- Eine rechte warhafftige hohe und götliche gruntliche underrichtung von der reinen forchte Gottes ann alle liebhaber der ewiger unentlicher warheit, aus Götlicher Schrifft angezeygt zum Preiss Gottes unnd heyll sines volcks in ewigkeyt . . . (1533).

The severity of Hoffman's position on disorderly conduct is shown by his attitude toward Claus Frey, whom he expelled from the brotherhood because of his fanatical conception of marriage which led him into polygamy.

Hoffman's confinement was at first mild. His friends were permitted to visit him and receive from him oral instruction and written information. In May 1533 he had to undergo two hearings. He defended himself successfully against the charge of having seditious plans. His defense was approximately as follows: He did not claim to be a prophet, but a witness of the supreme God and an apostolic teacher. This honorable title did not apply to the regular preachers, for all of them preached themselves rich. He did not oppose the office of preaching as a matter of principle; but pastors should be chosen from the oldest and most honest, and these should be permitted to own a home to shelter poor traveling brethren. But an apostle may own no property; he must always be ready to go wherever God may send him to proclaim the Word; his preaching would contribute only to his poverty; for he would have to leave all his possessions in exchange for a constant prospect of stocks and pillory.

Hoffman was also questioned (11-13 June) on the occasion of the General Synod of Strasbourg in June 1533. He clearly stated his faith. Bucer recorded these proceedings in his booklet, Handlung (1533), which was also translated into Dutch and distributed in the Netherlands, where it roused a storm of disappointment among the Anabaptists. For example, Cornelius Poldermann wrote a letter to the Strasbourg city council, asserting that he could produce 100 letters and books to prove that Bucer was in error in supposing that he had refuted Hoffman. Leendertz is of the opinion that he referred to two books that Hoffman had written in prison, and had sent to him through the warden's maid. These books are in the library of the University of Utrecht. Their titles are:

- Eine rechte warhaftige hohe und götliche gruntlicheunderrichtung von der reinen forcht Gottes an alle liebhaber der ewiger unentlicher warheit, auszz götlicher Schrift angezeigt zum preisz Gottes und seines volcks in ewigkeit. . . .

- Ein sendbrief an alle gotsförchtigen liebhaber der ewigen warheit, in welchem angezeigt seind die artickel des Melchior Hofmann, derhalben ihn die lerer zu Straszburg als ein ketzer verdampt . . . (1533). The foreword of this book is signed "Caspar Becker," Hoffman's pseudonym.

Bucer's book relates that Melchior Hoffman expected Strasbourg to be besieged about July 1533 before the return of Christ, whom he hoped to meet at the head of the 144,000. When Bucer called this to his attention, Hoffman postponed the date to a later time, but clung to the idea itself. Nor did an illness that struck him cause him to waver. The bitterness of his adherents, who were constantly increasing in number, was deep when they were denied the privilege of visiting and comforting their Elijah in his serious illness (Leendertz, 304).

Why the council did not release this harmless man, or in accord with custom banish him from the city as a foreigner at the close of the examination, is incomprehensible. Only the hope that he might eventually be converted saved him from execution. Even Bucer apparently counseled against releasing him, for a letter from Melanchthon, 10 October, expressly approves of the severe measures of the council against Hoffman (zur Linden, 344). Hofmann made the serious charge against the Strasbourg clergy (1536) that they had wanted to deliver him to the executioner. He reminded them that a court trial could be instituted against an elder, which he was in the eyes of God, only on the basis of two or three witnesses, and pointed to the example of Zwingli, who had to pay with his life for the blood of one man, that of the Anabaptist Felix Manz; they should lay aside all carnal hate and as soldiers of Christ fight only with spiritual weapons.

On 4 May 1534 Hoffman presented a petition to the magistrate, that he be cast into the dungeon, where, neither sun nor moon could shine, until God would have pity and bring the affair to an end, which would occur in 1534. In July of this year he wrote some pamphlets, which have been lost, under the pseudonyms of Caspar Becker and Michael Wächter; he was cross-examined about them on 9 September. His prison conditions were made more severe, but by bribing the wife of a guard he was able to maintain active communication with his group through books and letters.

In the spring of 1535 Hoffman thought there were indications that his redemption was near. On 15 April he requested the authorities to provide the city with food, for it would suffer hunger and want; in the third year of his imprisonment the Lord would come. During the siege the city need have no fear of its Anabaptists; only the masses, who lusted for the estates of the priests should be feared. The Anabaptists, who, like him, would not bear a sword, should be assigned to the walls. Great tribulation was to fall upon the imperial cities, and Strasbourg would be a seal for the rest, for, it would be the first to unfurl the banner of divine justice.

But this expectation also ended in disappointment. In April 1536 he complained about the severity of his jailers. He was in an unwholesome cell in the top story of the tower of Strasbourg, and had to live on inedible bread and water. He was completely isolated from the outside world. For lack of paper he filled the covers and blank parts of his books with writing. When these were removed he wrote his ideas down on 24 cloths, which were preserved in the Strasbourg archives until they were burned in the siege of the city in 1870. (For particulars about them see zur Linden, 380 ff., and Leendertz, 315 ff.) He requested alleviation of his difficult situation, a conversation with the Strasbourg preachers, some writing paper and ink. Nothing was granted.

On 5 May 1539, he had a talk with Peter Tasch and Johann Eysenburg, Anabaptist leaders who had left the brotherhood. In the spring, when he had suffered an attack of swellings on his face and legs, he had been moved into a more wholesome cell, and here the two men visited him in the hope of converting him; but the six-hour conversation was fruitless. Four additional conversations of five hours each followed. The rumor was spread among his adherents that he had recanted. (Hulshof discovered in Strasbourg a purported recantation by Hoffman in 1539, in which he sacrificed his rejection of infant baptism, and his teaching that sins committed after conversion could not be forgiven. See Hulshof, 180 f.)

Because of this rumor the Anabaptist Konrad v. Beyhel or Bühel risked his life to ask him whether he still held to the faith he had confessed eight years before, or had fallen from it as Tasch and Eysenburg claimed. Hoffman assured him that he was faithful to the truth as before, and warned Bühel to seek piety, live a quiet life, keep his marriage pure, and not cause any mobs, for he had no call to do so. Bühel should pass this admonition on to the brethren, warning them against holding secret meetings in the woods contrary to government orders, and holding up the Peasants' War, Zwingli, and the Münster revolt as warning examples. In general he should insist that they respect the government, especially in Strasbourg, for it was a pious government.

In June of 1539 the four Strasbourg preachers (Bucer, Capito, Hedio, and Zell) conferred with Melchior Hoffman, as they thought with success. But in November the prisoner informed the Ammeister of the city, on bits of paper cut from books, that the city should provide itself with food and munitions, for there would be great suffering in the coming siege; he had received high revelations, which he could give the council if they would furnish him paper and ink. These were refused, and his remaining books taken from him.

For two years (1540-1542) there is almost complete silence on Melchior Hoffman. He was said to have annoyed Hans Kunlin, a messenger of the council, by singing and shouting. Once again his hope for the future flickered up when, through bribery of the guards, his friends visited him and brought him good news of the Anabaptist movement. He thought his release was at hand; but the reverse happened. In January 1543 the council made his confinement still stricter. His cell was to be locked, the key kept in the chancery, and the door opened only in the presence of a member of the council. Food should be let down through the ceiling in a basket. Those who had accepted the bribe should be suitably punished.

On 16 April 1543, Hoffman asked the council to let him out into the air once more, and this request was granted. He also had temporary relief in June while repairs were made in his cell. In the autumn of 1543 he became so seriously ill that he was unable to receive his food. The council therefore had him transferred to the higher, better room, which the patient gratefully accepted. But Hoffman's health was broken and continued to deteriorate. On 19 November the council ordered that he be given the linens necessary to his care. Before the end of 1543 the sufferer died, a martyr to his faith.

Melchior Hoffman was an unusual person, a man of extraordinary gifts, of a consuming selfless zeal for the cause of the Lord Jesus, of a rare eloquence, combined with moral earnestness and a genuinely truthful character. This accounts for his mighty influence and great success with the masses. The amount of writing he could do in his unsettled life is amazing. Aside from his unbridled fantasy, his arbitrary interpretation of Scripture, and his fanatical view of the end-times, his writings also contain a wealth of sound Christian ideas and sober thoughts (see Samuel Cramer's article in BRN V, 127 ff.). His favorite ideas, (1) the hope of the imminent return of Christ and (2) his view of the Incarnation, that Jesus took His flesh not from Mary but out of her, were not generally accepted by the Anabaptists, although Menno Simons did adopt his view of the Incarnation. On the other hand, his determined insistence on freedom of religion, on evidence of the fruit of the Spirit, on sanctification of life, on believers' baptism, and on nonresistance, made essential contributions to the strengthening of Anabaptism. His teaching on the communion is still prevalent among the Mennonites of the Palatinate. The oath he at first rejected unconditionally, but later permitted it under certain circumstances, or even made use of it himself (zur Linden, 220). (If, however, Obbe Philips is the only authority for this statement, it is still open to question.) For the Münster affair Hoffman is no more responsible than Luther is for the Peasants' War. Granted that some of his teachings, such as the Incarnation and the imminent return of Christ, were carried into Münster by the "Wassenberg preachers" (Rembert, 299, 360 f.), nevertheless the fact remains that the social and moral aberrations in Münster find no source nor echo in either the life or teaching of Melchior Hoffman. His lasting significance lies in the fact that he transplanted the Anabaptist movement from the South to the North. Cramer calls him the father of Dutch Anabaptism.

Melchior Hoffman, even before his recantation, spoke of the Swiss Brethren in terms of disapproval and reproach. He sided with their opponents by holding them responsible for the well-known fratricide of Thomas Schugger in St. Gall, a man who was not an Anabaptist at all. Hoffman made the assertion that before the beginning of his labors no one had proclaimed the true Gospel. From his prison he sent word to the Swiss Brethren in Strasbourg, admonishing them to "stand still," and not to come together for worship without the consent of the authorities. As for the attitude of the Swiss Brethren toward Hoffman, they declared in the debate held in Bern in 1538 not only that he was not of their brotherhood but that his teaching was resisted by them "with all earnestness." -- Christian Neff

1990 Update

Melchior Hoffman was the most significant early propagator of Anabaptism in northern Germany. Christian Neff's excellent article based on the thorough scholarship of Leendertz, zur Linden, and Kawerau needs only minor revisions.

Biography

Hoffman came from a family of middle artisan status in Schwäbisch-Hall. He arrived in Livonia sometime during 1521 or 1522, earlier than previously thought. During his four- to five-year stay he mastered the Low German language spoken there. It was in Livonia that he experienced the coming of the Reformation, sided with Reformers and became involved in iconoclastic disturbances. Although Hoffman considered himself a Lutheran, Pater has suggested an early influence by Karlstadt. Hoffman's views on the Eucharist and on the church as a charismatic community of equal brothers and sisters thus differed from the view held by Luther. Hoffman's expulsion from Livonia, his ministry in Sweden and Schleswig-Holstein, and his break with Luther need no reiteration. Hoffman's conversion to Anabaptism presumably took place during his first stay at Strasbourg. Deppermann has suggested contact with the branch of Anabaptism that stood in continuity with a Denck-Kautz-Hut line. Given Hoffman's strong sense of prophetic calling, Deppermann speculates that he initiated adult baptism on his own, and that it would be wrong therefore to place him into any successio Anabaptistica, certainly not one originating in Zürich. In need of correction is the notion of a second visit by Hoffman to Strasbourg in the fall of 1530. His first stay extended from June 1529 to April 1530. The wrong dating of a document by Röhrich had led to the postulation of a return visit in the fall of 1530 (TA Elsaß I, 309-310).

Hoffman's so-called "recantation" remains controversial. The document, discovered by Hulshof, had been solicited from Hoffman by Peter Tasch in conjunction with the little known "second synod" of Strasbourg, 26-28 May 1539. According to this document and statements made later by Blesdijk, Hoffman eventually retracted all the positions for which he had been condemned at the first synod (1533). Needless to say this made him no less a martyr—a martyr of conscience, who suffered more than ten years imprisonment. Curiously, records indicate that shortly after the assumed death of Melchior Hoffman in Strasbourg (late 1543 or early 1544), an Anabaptist, also named Melchior Hoffman, appeared in Hoffman's home area of Schwäbisch-Hall (Packull, 1983).

Teaching

It is now recognized that Hoffman's pre-Anabaptist views were not simply derived from Luther or Karlstadt. It appears that his visionary apocalyptic spiritualism had roots reaching back to the Spiritual Franciscan tradition. His insistence on the superiority of the spirit over the letter was supported by a medieval allegorical hermeneutic, while the visions of Johns's Revelation served as the keyhole through which he scanned the rest of Scripture. In his "mature" phase, Hoffman combined these elements with a form of Anabaptism stamped by Denck and Hut. Although the resulting synthesis was Hoffman's own, it would be anachronistic to accuse him of "arbitrary interpretation of Scripture' and of "unbridled fantasy" as Neff, following others, had done. To be sure, Hoffman's ministry remained unique. Perhaps the strong anticlericalism of his message provides a partial explanation for his popularity. Even as an Anabaptist leader he attempted consistently to win the authorities for his reform program. His suspension of baptism for two years was equally unique. Unusual for an uneducated artisan were Hoffman's lengthy biblical commentaries as well as the many other publications.

Significance

It has been argued that Hoffman's ministry proved counterproductive (Deppermann). The social disorders that followed his preaching in Livonia helped frighten the landed nobility back into the old church, and hastened the triumph of conservative forms of Lutheranism in the cities. A similar case can be made for Schleswig-Holstein. The apocalyptic excitement aroused in Strasbourg led to reactionary measures that proved detrimental to all nonconformists. The disaster of Münster had far-reachng consequences for Anabaptists everywhere. Münster itself was recatholicized. However, assessments of Hoffman's historical significance must take account of the fact that his labors in the various territories coincided with the introduction of the Reformation in them. That his influence waxed and waned with popular initiative helps to explain why for a brief period the Melchiorite movement took on mass dimensions in The Netherlands. If Münster constituted an expression of that movement, so did the peaceful remnant gathered by Menno Simons. Hoffman remains of historical significance precisely because he introduced Anabaptism to the North.

Sources

To the 18 writings of Hoffman cited by Neff, 9 others originating with Hoffman or his closest collaborators can be added. Deppermann has listed all these documents as well as their present location. We provide in an abridged form only the titles not mentioned in Neff's article.

- Dat Nikolaus Amsdorff der Meydeborger Pastor/ nicht weth/ wat he setten/ schriuen edder swetzen schal/ darmede he syne logen bestedigen moge/ unde synen gruweliken anlop. Kiel: Hoffman, 1528. Reproduced by Gerhard Ficker under the title, "Melchior Hoffman gegen Nikolaus Amsdorff," in Schriften des Vereins für Schleswig-Holsteinische Kirchengeschichte 5 (1928).

- Das Niclas Amsdorff der Magdeburger Pastor ein lugenhafftiger falscher nasen geist sey/ offentlich hewiesen durch Melchior Hoffman. Kiel: Hoffman, 1828. Reproduced by Gerhard Ficker in Schriften des Vereins für Schleswig-Holsteinische Kirchengeschichte 4 (1926).

- (Das] Erste Capitel des Evangelisten St. Mattheus (1528), Vorrede. Reprinted by Johannes Melchior Krafft in Ein Zweyfaches Zwey-hundert-Jähriges Jubel-Gedächtnis. Hamburg, 1723: 440-445.

- Dat Boeck Cantica Canticorum odder dat hoge leedt Salomonis uthgelecht dorch Melchior Hoffman. Kiel: Hoffman, 1529.

- M. H. [Melchior Hoffman]. Das ware trostliche unnd freudenreiche Euangelion. Straßburg: Jakob Cammerlandere, 1531.

- M. H. [Melchior Hoffman]. Een waraftyghe tuchenisse under gruntlyke verclarynge wo die warden tho den Ro. IX Ca. van dem Esau und Jacob soldeen verstaen worden. Deventer: Albert Paffraet, 1532.

- [Hoffman, published by Poldermann], Die Epistel des Apostell Sanct Judas erklert unnd ... außgelegt. Hagenau: Valentin Kobian, 1534. Reproduced in Krebs, Manfred and Hans Georg Rott, eds. Quellen zur Geschichte der Täufer, vol. 8: Elsaß, vol. 2: Stadt Strasbourg, 1533-35, Quellen und Forschungen zur Reformationsgeschichte, 27. Gütersloh, 1960: no. 479: 241-245.

- Eisenburgk, Johannes [presumably with Hoffman]. Die Epistel deß Apostels S. Jacobs erklart/ und . . außgelegt. Straßburg: Jakob Cammerlander, 1534. Reproduced in part in Krebs, Manfred and Hans Georg Rott, eds. Quellen zur Geschichte der Täufer, vol. 8: Elsaß, vol. 2: Stadt Strasbourg, 1533-35, Quellen und Forschungen zur Reformationsgeschichte, 27. Gütersloh, 1960:no. 480: 245-248.

- Beck, Caspar [pseudonym]. Eyn sendbrieff an den achtbaren Michel wachter/ in welchem eroffnet würt/ die uberauß greuwliche mißhandlung/ die in vergangnen zeyten zu Jerusalem wider dye ewige worheit und der selbigen zeugen gehandlet ist/. Hagenau: Valentin Kobian, 1534. Reproduced in "Ein Sendbrief Melchior Hofmanns aus dem Jahre 1534," ed. b E. W. Kohls, Theologische Zeitschrift 17 (1961): 356-365.

- "Bekentnuss des Melchior Hofmanns vom kindertauf," published by Hulshof in Geschiednis van de Doopsgezinden to Straatburg: 180-181.

- "Summarium dess was Melchior Hoffman im Thurm uff 24 Tücher geschriben hat (1537)," ed. by T. W. Röhrich, Zeitschrift für die historische Theologie 30 (1860): 104-106.

It should be noted that Pater and others believe that the Dialogus was really Karlstadt's work based on Hoffman's account. Neff was mistaken when he believed that pamphlets written under the pseudonyms of Caspar Becker and Michael Wächter had been lost (see item 9 above). The name Caspar Beck, if it hides the same author as the pseudonym Caspar Becker, refers to Peter Tasch (Packull, "Peter Tasch," MQR, 1988). It should also be noted that Hoffman's Auslegung described by Neff as a pamphlet was Hoffman's major treatise consisting of more than 150 pages. Hutterite copyists transcribed and rewrote this commentary, in the process losing the author's name. "The Ordinance of God," was in part translated by G. Williams in Spiritual and Anabaptist Writers, 1957: 182-203. -- Werner O. Packull

Bibliography

Cornelius, C. A. Geschichte des Münsterischen Aufruhrs in drei Büchern. Leipzig, 1860: 75 ff., 282 ff.

Cramer, Samuel and Fredrik Pijper. Bibliotheca Reformatoria Neerlandica, 10 vols. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1903-1914: Volume 5.

Doopsgezinde Bijdragen (1919): 124 ff.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. II: 326-35.

Hulshof, A. Geschiedenis van de Doopsgezinden to Straatsburg van 1525 tot 1557. Amsterdam, 1905.

Kawerau, Peter. Melchior Hoffman als religiöser Denker. Haarlem, 1954.

Krohn, B. N. Geschichte der fanatischen und enthusiastischen Wiedertäufer vornehmlich in Niederdeutschland : Melchoir Hofmann und die Secte der Hofmannianer. Leipzig, 1785.

Kühler, Wilhelmus Johannes. Geschiedenis der Nederlandsche Doopsgezinden in de Zestiende Eeuw. Haarlem: H.D.Tjeenk Willink, 1932: 52-77.

Leendertz, W. L. Melchior Hofmann. Haarlem, 1883.

Rembert, Karl. Die "Wiedertäufer" im Herzogtum Jülich. Berlin: R. Gaertners Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1899.

Sax, E. B. Rise and Fall of the Anabaptists. London, 1903: 95 ff.

Schoeps, H. J. Vom himmlischen Fleisch Christi. Tubingen, 1951: 37 ff.

Visscher, H. and L. A. van Langeraad. Biographisch Woordenboek von Protestantsche Godgeleerden in Nederland, A-L. I, Utrecht. later by J. P. de Bie and J. Loosjes. The Hague 1903- :IV, 121-34

zur Linden, F. O. Melchior Hofmann, ein Prophet der Wiedertäufer. Haarlem, 1885.

Important primary sources related to Hoffman's life and theology include:

Amsdorf, Nikolous. "Eine Vermanung an die von Magdeburg, das sie Bich fur falsch propheten zu hüten wissen." Magdeburg, 1527.

Amsdorf, Nikolous. "Das Melchior Hoffman ein falscher Prophet und sein leer vom jüngsten Tag unrecht, falsch und wider Gott ist; an alle Heilige und Gläubige an J. Chr. zu Kiel und in ganzen Holstein." Magdeburg, 1528.

Amsdorf, Nikolous. "Das Melchior Hoffman nicht ein wort cuff mein Büchlein geantwort hat." Magdeburg, 1528.

Blesdijk, Nikolaas. Historia vitae, doctrinae, ac rerum gestarum Davidis Georgii haeresiarchae. Deventer, 1642.

Blesdijk, Nikolaas. "Van den Oorspronck ende anvanck des sectes welck men wederdoper noomt," a manuscript rediscovered by S. Zilstra in the Joris Lade at the University Library of Basel. described by Zilstra, see below.

Bugenhagen, J. Acta der Disputation zu Flensburg/ die sache des Hochwirdigen Sacraments betreffend, im 1529. Jar. Wittenberg, 1529.

Bugenhagen, J. Eynne rede yam sacramente. Dorch Joannem Bugenhagen Pomeren tho Flensborch nah Melchior Hoffmans dysputatien geredet. Hamburg, 1529.

Bucer, Martin. Handlung inn dem offentlichen gesprech zuStrasbourg jüngst im Synodo gehalten/ gegen Melchior Hoffman/ durch die Prediger daselbst. Strasbourg, 1533.

Schuldorp, M. Breef an die Glövigen der Stadt Kyll weder eeren Prediger Melchior Hoffman. Hamburg, 1528. The title as reconstructed by Pater.

Wydenszehe [Weidensee], E. Eyn underricht uth der hillighen schrufft/ Melchior Hoffmans sendebreff/ darynne he schryffy/ dat he nycht bekennen kone dat eyn stucke liiflikes brodes syn Godt sy/ belangende. 1529.

Secondary accounts related to Hoffman included the following:

Crous, Ernst. "Von Melchior Hofmann zu Menno Simons." Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter 19, N.F. 15. (1962): 2-14.

Deppermann, Klaus. "Hoffmans letzte Schriften aus dem Jahre 1534." Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte.63. (1972): 72-93.

Deppermann, Klaus. "Die Strassburger Reformatoren und die Krise des oberdeutschen Täufertums im Jahre 1527." Mennonitshce Geschichtsblätter. 30, N.F. 25. (1973): 24-41.

Deppermann, Klaus. "Melchior Hoffmans Weg von Luther zu den Täufern." Umstrittenes Taufertum. 1975: 173-205.

Deppermann, Klaus. "Melchior Hoffman and Strasbourg Anabaptism." The Origins and Characteristics of Anabaptism ed. by Marc Lienhard. Hague: Nijhoff, 1977: 216-19.

Deppermann, Klaus. "Melchior Hoffman: Widersprüche zwischen Lutherischer Obrigkeitstreue und apokalyptischen Traum." Radikale Reformatoren ed. H.J. Goertz. Münich, 1978: 155-66. (English translation in Profiles of Radical Reformers. Scottdale, 1982: 178-190).

Deppermann, Klaus. Melchior Hoffman: Soziale Unruhe und apokalyptische Visionen im Zeitalter der Reformation. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, 1979. English translation Edinburgh: T. and T. Clark, 1986.

Klaassen, Walter. "Eschatological Themes in Early Dutch Anabaptism." The Dutch Dissenters, ed. by I. B. Horst. Leiden: Brill, 1986: 15-21.

Noll, Mark A. "Luther Defends Melchior Hofmann." Sixteenth Century Journal 4 (1973): 47-60.

Packull, Werner O. "Hutterite Book of Medieval Origin Revisited. An Examination of the Hutterite Commentaries on the Book of Revelation and their Anabaptist Origin." Mennonite Quarterly Review 56 (1982): 147-168.

Packull, Werner O. "Melchior Hoffman-A Recanted Anabaptist in Schwäbisch Hall?" Mennonite Quarterly Review 57 (1983): 83-111.

Packull, Werner O. "Der Hutterische Kommentar der Offenbarung des Johannes: Eine Untersuchung seines Täuferischen Ursprungs." Die Hutterischen Taufer Geschichtlicher Hintergrund und handwerkliche Leistung. Munich, 1985: 29-37.

Packull, Werner O. "Melchior Hoffman's Experience in the Livonian Reformation: The Dynamics of Sect Formation." Mennonite Quarterly Review 59 (1985): 130-146.

Packull, Werner O. "A Reinterpretation of Melchior Hoffman's Exposition Against the Background of Spiritual Franciscan Eschatology with Special Reference to Peter John Olivi." The Dutch Dissenters, ed. by I. B. Horst. Leiden: Brill, 1986: 32-61.

Packull, Werner O. "Peter Tasch: From Melchiorite to Bankrupt Wine Merchant." Mennonite Quarterly Review 62 (1988): 276-295.

Packull, Werner O. "Sylvester Tegetmeier, Father of the Livonian Reformation: A Fragment of His Diary." Journal of Baltic Studies 16. (1986): 343-356.

Pater, Adrian. "A Study of Selected Doctrines in Melchior Hoffman." ThD dissertation: New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, 1978.

Pater, Calvin A. Karlstadt as the Father of the Baptist Movements: The Emergence of Lay Protestantism. U. of Toronto Press, 1984.

Pater, Calvin A. "Melchior Hoffman's Explication of the Songs [!] of Songs." Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte 67 (1977): 173-191.

Stayer, James M. Anabaptists and the Sword. Lawrence, KS: Coronado Press, 1972; revised ed. 1976.

Voolstra, Sjoue. Het woord is vlees geworden: De melchioritisch-menniste incarnatieleer. Kampen, 1982.

Wunder, G. "Uber die Verwandtsehaft des Wiedertäufers Melchior Hoffman." Der Hallquell: Blätter fur Heimatkunde des Haller Landes 23 (1971): 21-23.

Zijlstra, S. Nicolaas Meyndertsz van Blesdijk. Assen, 1983.

| Author(s) | Christian Neff |

|---|---|

| Werner O. Packull | |

| Date Published | 1987 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Neff, Christian and Werner O. Packull. "Hoffman, Melchior (ca. 1495-1544?)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1987. Web. 24 Nov 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Hoffman,_Melchior_(ca._1495-1544%3F)&oldid=146778.

APA style

Neff, Christian and Werner O. Packull. (1987). Hoffman, Melchior (ca. 1495-1544?). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 24 November 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Hoffman,_Melchior_(ca._1495-1544%3F)&oldid=146778.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, pp. 778-785; v. 5, pp. 384-386. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.