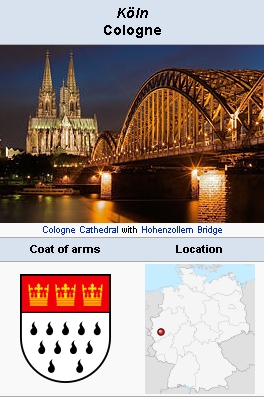

Cologne (Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)

Cologne (Köln), former capital of the Prussian Rhine province, (1950 population, 590,000; 2007 population, 991,395), was already in Reformation times a great, powerful city, an archiepiscopal see, had a highly regarded, well-attended university, was the center of an extensive trade, the fortress of Catholicism and at the same time the place of refuge of all the non-Catholic movements of the time, among which the Anabaptists played a prominent part. Numerous traces of pre-Reformation parties are also to be found here. Cologne can be called a center of the Waldensian groups, who held their meetings in secret basements and weavers' rooms. Wherever they came into the open or were discovered, they became victims of the Inquisition.

In the protocol of the Cologne council, 24 August 1531, an archbishop's letter is mentioned which states that there were Anabaptists in the city. For two years nothing more is heard of them. In 1533 the Anabaptists began a greater activity. Perhaps the first Anabaptists were burned at this time (Rembert, 381).

In the center of the movement was the native of Cologne, Gerhard Westerburg. He had gone to Münster early in 1534 and been baptized in Knipperdolling's house by Henric Rol. With his brother Arnold he baptized many in Cologne. The movement was violently suppressed.

Later a congregation of peaceful Anabaptists had also formed at Cologne. When and how it came into being is not known. Menno Simons may have found them there, and may have contributed much to strengthening and building them up in his two years in the city territory (1544-1546). Elder Theunis van Hastenrath baptized here about 1550 (Doopsgezinde Bijdragen 1909, 122). In 1551 a notice was issued by the Duke of Jülich to the city council of Cologne, that Schröder Nellis on the Domhof and the cobbler Heinrich on the Krummbüchel were Anabaptists. This unleashed a cruel persecution. By far most of those seized in the city were not natives, but had come from outside. To prevent further influx of strangers whose creed was not known, the council issued the order not to tolerate the "unchristian, damned sect of Anabaptists," who, expelled from other places, had come here to hold their conventicles. All outsiders must present an attest from their home town concerning their origin, creed, etc., before they may be lodged.

When Thomas von Imbroich came to Cologne in 1554, he was introduced to the preacher of the brotherhood there by Johann Schuhmacher, a citizen of Cologne. He found a large congregation, most of whom had probably not been baptized yet as adults. The council issued an edict in 1554 warning that the imperial laws would be strictly observed in all cases of adult baptism. On 10 July 1555 this announcement was repeated. Two years later Thomas von Imbroich was arrested and executed on 5 March 1558. In the foreword of his "confession" to the council he protests his innocence of any seditious intentions with warmth and. dignity.

In 1560 the city council was informed that the Anabaptist congregation there numbered 40 members, and that their leader and preacher was the capmaker, Heinrich Krufft, "a small squarely built man"; they met frequently in the Neuenahrer or Moersischen Hof. They had appointed a regular "caller" whose duty it was to notify members of the meetings (Zischt für hist. Theol., 1860, 165, where an invitation issued by the Strasbourg Anabaptists is given verbatim).

In 1561 three Anabaptists were executed by drowning at Cologne, one of them being Georg Friesen, and in 1562 two others were arrested. The church had increased to over 100 members. Faithfully they continued to meet in secret until they were betrayed by one of their own members in 1564. Thirty-three women and 24 men were thereupon seized and imprisoned in the various towers and gates of the city. Most of them were artisans, winedressers, washerwomen, and maids from other towns. Only two women belonged to the higher classes, the wife of the magistrate of Born and the Stiftsfräulein Margarete Werninckhofen. Among those arrested was Matthias (or Matthijs) Servaes of Ottenheim, who was put to death on 30 June 1565.

In August, September, and October 1565 a group of Anabaptists who "persisted stiff-necked in all their known errors" were expelled from the city; any who returned would be punished with death within 24 hours without mercy. About 1570 the well-known elder from Flanders, Hans Busschaert de Wever, lived in Cologne whither many Mennonites fled from Belgium in the next few years. Among those who had come from Antwerp were the parents of Joost van den Vondel, who was born at Cologne in 1587.

The numerous protocols of the cross-examinations shed some light on the nature and inner life of the congregation. At the head stood the "principal preacher," called elder; there were four of them; they had the oversight and rule over the church. Preachers were ordained by them. They served without fixed salary; they received only freewill gifts for their support. In 1609 a remarkable case is mentioned, where a preacher in Cologne received a daily income of six "albus" (Rembert, 509, note 3). The care of the poor was in charge of the deacons. In receiving members by baptism they acted with great caution. Scarcely one third of those who regularly attended their meetings were received in full membership. Anyone who maintained friendship with the Papists or other churches was regarded as a "sawed-off limb," and had to make confession before all the congregation.

Concerning communion services the following is known: "When communion was distributed the preacher took the bread and broke a piece of it for each, and as soon as it was given out and each had a piece in his hand, the preacher also took a piece for himself, put it into his mouth and ate it; and immediately, seeing this, the congregation did the same. The preacher, however, used no words, no ceremony, no blessing. As soon as the bread was eaten, the preacher took a bottle of wine or a cup, drank, and gave each of the members of it. On this wise they observed the breaking of bread."

In baptism the candidate knelt, the one administering baptism took water into his hand from a jug, poured it on the candidate's head with the words, "I baptize you on the faith you have confessed and accepted, in the name of the Father. . . ." "Baptism does not save, only obedience does," said their creed. They recognized each other by the greeting, "Peace be with you!" They rejected community of goods. "The more powerful and wealthy give according to their means to the preachers and the poor and needy, so that they do not starve."

The church in Cologne had connections with Anabaptists in Holland (Doopsgezinde Bijdragen 1898, 109), Switzerland, and South Germany. In 1576 Hendrik von Berg, a member of the Cologne congregation, corresponded with the Dutch Elder Hans de Ries. In the older books such as those by Burgmann, Hoornbeek, etc., a letter written by the Swiss Brethren to their brethren in Cologne is mentioned. In 1591 a conference of German and Dutch Mennonites met in Cologne to reach an agreement on several important points of church life. This took place in the Concept of Cologne (reprinted in Hege, Die Täufer in der Kurpfalz, 150-52). On the part of the congregation of Cologne the concept was signed by Ameldonck Leeuw, who is already mentioned as a preacher in 1569.

A church inspection made in 1597 in the archbishopric yielded a sad picture of conditions in the Catholic Church, which explains why Protestant preachers won large followings. There were also many Anabaptists in the city. Against them the mayors issued a stern warning on 30 April 1601, that they must leave the city within a week on penalty of death. The houses in which they held their services or whatever conventicles the heretics had, should be confiscated, the owners subject to the death penalty, the auditors be fined 100 guilders. Non-Catholic baptism should be fined with 50 instead of 25 guilders as hitherto. All Protestants who had come to Cologne after 1590 must give up their citizenship and the protection of the city. By the end of May 300 persons, probably most of them Mennonites, had left the city.

After this, little or nothing is heard of the Mennonite church in Cologne. In 1637 a member of the congregation of Cologne came to Amsterdam, bringing along an attestatie.

Bibliography

Ernst, Victor. Briefwechsel des Herzoges Christoph von Wirtemberg. Im Auftrag der Kommission für Landesgeschichte. Stuttgart, W. Kohlhammer, 1899-1907: v. III, 335.

Hege, Christian. Die Täufer in Der Kurpfalz: Ein Beitrag Zur Badisch-Pfälzischen Reformationsgeschichte. Frankfurt am Main: Kommissionsverlag von H. Minjon, 1908.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. II, 522-24.

Hoop Scheffer, Jacob Gijsbert de. Inventaris der Archiefstukken berustende bij de Vereenigde Doopsgezinde Gemeente to Amsterdam, 2 vols. Amsterdam: Uitgegeven en ten geschenke aangeboden door den Kerkeraad dier Gemeente, 1883-1884: I, 401, 404, 466, 468, 469.

Rembert, Karl. Die "Wiedertäufer" im Herzogtum Jülich. Berlin: R. Gaertners Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1899: 380 f.

Weiler, Peter. Die kirchliche Reform im Erzbistum Köln. Münster i.W : Aschendorff, 1931.

Maps

| Author(s) | Christian Neff |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1956 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Neff, Christian. "Cologne (Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1956. Web. 19 Jan 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Cologne_(Nordrhein-Westfalen,_Germany)&oldid=120969.

APA style

Neff, Christian. (1956). Cologne (Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 19 January 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Cologne_(Nordrhein-Westfalen,_Germany)&oldid=120969.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, pp. 642-643. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.