Difference between revisions of "Christology"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m |

m (→1990 Article: Resized images.) |

||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

Denck's Christology has been markedly less influential. As are other areas of his thought, [[Denck, Hans (ca. 1500-1527)|Denck's]] Christology is complex and difficult to categorize. Nonetheless, it had a mystical and universalizing tendency. It focused on the incarnate Word more than on the incarnate Christ. The eternal or inner Word suffered not only in the incarnate Lamb Jesus Christ, but had also suffered before and suffers since in the elect. Similarly, the eternal Logos which was victorious in Jesus Christ, has been victorious in the elect from the beginning and shall be so until the end. | Denck's Christology has been markedly less influential. As are other areas of his thought, [[Denck, Hans (ca. 1500-1527)|Denck's]] Christology is complex and difficult to categorize. Nonetheless, it had a mystical and universalizing tendency. It focused on the incarnate Word more than on the incarnate Christ. The eternal or inner Word suffered not only in the incarnate Lamb Jesus Christ, but had also suffered before and suffers since in the elect. Similarly, the eternal Logos which was victorious in Jesus Christ, has been victorious in the elect from the beginning and shall be so until the end. | ||

| + | [[File:WengerJC.jpg|200px|thumb|right|''J. C. Wenger'']] | ||

| + | [[File:YoderJohnH1.jpg|200px|thumb|right|''John Howard Yoder (1978)'']] | ||

| + | [[File:KaufmanGordon.jpg|200px|thumb|right|''Gordon Kaufman'']] | ||

| + | [[File:KrausCNorman.jpg|200px|thumb|right|''C. Norman Kraus'']] | ||

This Logos Christology provides the basis for the theology of the divine in every human. Although the humanity as well as the divinity of Jesus is important for [[Denck, Hans (ca. 1500-1527)|Denck]], the two natures seem to remain somewhat separated from each other. The historical Jesus or the [[Bible: Inner and Outer Word|outer Word]] is important primarily as the teacher and example, namely, as the witness to the inner Word, which provides the means of deification for the disciple. Denck emphasized the unity of Christ's will with God's will, and the freedom of the will to be one with God. Some of his followers found his synthesis difficult to maintain and seriously questioned orthodox Christological and trinitarian doctrines. | This Logos Christology provides the basis for the theology of the divine in every human. Although the humanity as well as the divinity of Jesus is important for [[Denck, Hans (ca. 1500-1527)|Denck]], the two natures seem to remain somewhat separated from each other. The historical Jesus or the [[Bible: Inner and Outer Word|outer Word]] is important primarily as the teacher and example, namely, as the witness to the inner Word, which provides the means of deification for the disciple. Denck emphasized the unity of Christ's will with God's will, and the freedom of the will to be one with God. Some of his followers found his synthesis difficult to maintain and seriously questioned orthodox Christological and trinitarian doctrines. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Another Anabaptist theologian and church leader during the 16th century was [[Marpeck, Pilgram (d. 1556)|Pilgram Marpeck]]. His influence at the time may have almost equaled that of Menno Simons. Although he shared an interest in relating Christology to the concepts of salvation and the church, he rejected the heavenly flesh Christology and articulated a distinctive view of Christ's humanity and its relation to his divinity. | Another Anabaptist theologian and church leader during the 16th century was [[Marpeck, Pilgram (d. 1556)|Pilgram Marpeck]]. His influence at the time may have almost equaled that of Menno Simons. Although he shared an interest in relating Christology to the concepts of salvation and the church, he rejected the heavenly flesh Christology and articulated a distinctive view of Christ's humanity and its relation to his divinity. | ||

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

See also [[Judaism and Jews|Judaism and Jews]]; [[Sciences, Natural|Sciences, Natural]] | See also [[Judaism and Jews|Judaism and Jews]]; [[Sciences, Natural|Sciences, Natural]] | ||

| + | |||

= Bibliography = | = Bibliography = | ||

Beachy, Alvin J. <em>The Concept of Grace in the Radical Reformation.</em> Nieuwkoop: B. de Graaf, 1977: 79-86, 178. | Beachy, Alvin J. <em>The Concept of Grace in the Radical Reformation.</em> Nieuwkoop: B. de Graaf, 1977: 79-86, 178. | ||

Revision as of 07:36, 15 May 2014

1955 Article

The Incarnation of Christ (Christology) is a doctrine which has been a subject of controversy at various times in church history. Those emphasizing the humanity of Christ at the cost of His deity are probably better known than those emphasizing the divinity more than the humanity. A large wing of the early Anabaptists emphasized the deity of Christ more than the regular Catholic and Protestant churches did, with their historic orthodox creeds. However, this emphasis did not originate with the Anabaptists, but had its roots in early Christendom. The Valentinians at the time of Tertullian emphasized the divinity of Christ and minimized His humanity to the point that they considered Christ born of the Virgin Mary as if He had been passing through her body "as through a pipe." taking none of her human flesh, in order to assure that the Saviour had "other flesh" than that of fallen man so that He would not have part in original sin. Even stronger is the emphasis placed on this by the Gnostic Marcion. Apollinaris and his followers continued this line of thought emphasizing that only thus humanity has a guarantee of salvation. "Our human nature was accepted by Him so that He became a perfect organ of God" (Schoeps, 13). During the Middle Ages this particular emphasis almost completely disappeared with the exception of such groups as the Bogomiles and Cathars. During the Reformation this concern reoccurs particularly among some of the "left-wing" reformers.

In a 1951 study devoted to this subject, H. J. Schoeps (Vom himmlischen Fleisch Christi) states that Caspar Schwenckfeld was the first of the reformers to emphasize the teaching of the "heavenly flesh" of Christ and that he was directly influenced by the Greek Fathers (26). Schwenckfeld believed in a sinless "glorified humanity" of Christ. "If Christ had the characteristics of a sinful creation, He could not represent us in the presence of God" (28). Schoeps states that Schwenckfeld's concern in this matter was that mankind can be "glorified" or become divine only if Christ was divine. His Christology was closely related to his views regarding the Lord's Supper. "Only through Christ's heavenly body is the spiritual influence from above guaranteed, because only through the glorified humanity of the risen Christ can believers be filled and fed with the Holy Spirit" (36). "Through His spiritualized, raised, and glorified (divine) flesh, Christ, as a second Adam, draws mankind toward Himself into spirituality" (36).Hoffman

Melchior Hoffman was the originator of this peculiar teaching regarding the incarnation of Christ, as far as the early Anabaptists are concerned. To what extent he was influenced by Schwenckfeld or Sebastian Franck, whom he met in Strasbourg, has not yet been conclusively established. Schwenckfeld says concerning his influence along these lines, "They have both (Hoffman and Franck) taken their errors from our truth, like spiders who suck poison out of a beautiful flower" (Corpus Schwenckfeldianorum V, 522 f.). Even though the above influences may have started Hoffman out on his way along these lines, he soon went his own way. It has been definitely established that Hoffman's ideas were taken over by Menno Simons, Dirk Philips, and other representatives of the early Dutch Anabaptists, who added hardly anything new.

This peculiar view regarding the Incarnation was widespread among the early Dutch Anabaptists. That it was also found among the followers of Melchior Hoffman in South Germany as late as 1555 is apparent in the introduction to the "Agreement of the brethren and elders congregated at Strasbourg regarding the question of the source of Christ's flesh," which stated that the ministers and elders had been approached to give an account along these lines by "the followers of Hofmann, as well as the Dutch brethren." This distinction between the two would indicate that some of them were located in South Germany or in the vicinity of Strasbourg (Brons, 97). At this Anabaptist conference it was emphasized that since the Bible states both that Christ had His flesh from heaven and that He received it from Mary we should "not attempt to know more than can be known," and "that reason should be subordinated to the obedience of Christ."

One of the basic differences between the early Dutch Anabaptist leaders and Schwenckfeld was the claim of the Dutch that Christ was born "in Mary" and not "of Mary," that Mary did not furnish the flesh of the Saviour, but merely His nourishment. Schwenckfeld does not go so far, stating that Christ received the "flesh and tabernacle of His body from Mary, the virgin," and emphasizes that he is not "Hoffmenisch," although he considers the flesh of Christ of "divine origin" (Corpus Schwenckfeldianorum VII, 304). Schwenckfeld's views are closely related to his peculiar view of the "deification" of the children of God, in which process he considered it necessary that the flesh of Christ be of divine origin. Hoffman's and Menno's views are closely related to their concept of the Christian church. The church of Christ, which is the body of Christ, can only be transformed into this fitting close relationship to Him if the sole cause of this act is Jesus Christ, her Saviour and head. The church, or the body of Christ, can be without wrinkle and blemish only if Christ was without sin and His human substance was of divine origin. Franck, who shared somewhat the Anabaptist emphasis on the divinity of Christ, did not have their concern regarding the establishment of a visible, pure church and he, therefore, did not agree with them along these lines.

It is here where an apparently speculative thought becomes a basic doctrine of salvation. It was because of this reasoning that the peculiar view regarding the incarnation of Christ became a very important doctrine for Menno and his followers. Although Menno asserts (Complete Writings, 430, 439) that he is not particularly teaching and preaching this view, but that he is constantly being lured to defend it, we must conclude that he would not have been so voluminous in writing about this subject and defending it if it had not been basic for him, and that he would not have been attacked by his opponents if he had kept this as a "secret" doctrine. At nearly all public discussions with opponents this matter was on the agenda and discussed in detail. For him and his followers this was an essential part of their doctrine. This is also evidenced by the fact that Adam Pastor was ousted because he stressed the humanity of Christ, and denied His essential deity because he thought God and man (Jesus) could not be of the same essence (Krahn, 67 ff.). In oral and written discussions, this doctrine was a matter of controversy between Menno and a Lasco, Micronius, and Faber, as well as at official religious debates at Leeuwarden and Emden. In the writings of Melchior Hoffman, Menno Simons, and Dirk Philips this subject matter is discussed, defended and elaborated on at length. They object seriously to speaking of two "persons" in Christ, the divine and the human, on the grounds that the divine act in the birth of Christ cannot be described in these terms.

At the great Anabaptist conference at Strasbourg in 1555 it was emphasized that since the Bible states both that Christ had His flesh from heaven and that He received it from Mary we should "not attempt to know more than can be known" and "that reason should be subordinated to the obedience of Christ." When pressed by the Reformed for answers along these lines at the Frankenthal disputation in 1571, the Anabaptists seem to have been intentionally unexplicit. The question posed was: "Concerning Christ. Whether Christ received the nature of His flesh from the substance of the flesh of the Virgin Mary or elsewhere." This question is definitely directed against the teaching of Melchior Hoffman along these lines. Diebold Winter finally said, "We request time to think it over. We are flooded with many words. If there is anything to them we cannot grasp it. We must fear God and cannot yet accept them in such manner."

In an undated edict against the Anabaptists Philipp of Hesse stated that "those who hold that Christ did not receive His humanity from the blood of Mary through the work of the Holy Spirit" (TA Hessen, 33) were not permitted to live in his realm. This would indicate that there were some followers of Hoffman in South Germany who shared his views on the incarnation. Also Caspar Schwenckfeld stated that "many Anabaptists, particularly in Alsace and the Netherlands," held this view and that he had "debated with many of them, also with M. Hofmann, and proven by Scripture that Christ had really taken His flesh from the Virgin Mary" (Schoeps, 28). This is a quotation from his book Vom Fleisch Christi ... (1561). Already around 1540 he had written a booklet Vom Fleische Christi ... in which he attacked Melchior Hofmann (Corpus Schwenckfeldianorum VII, 281 ff.). In his letter to W. Thalhäuser dated 1 February 1539 (Corpus Schwenckfeldianorum VI, 483), he states that he has succeeded in convincing some of the followers of Hoffman, including leaders, to accept the true teaching concerning the incarnation of Christ. How widespread Hoffman's views pertaining to this doctrine were in Middle and South Germany has not been studied. That they may have been present as late as 1577 is possible, since the Formula of Concord starts its condemnation of the Anabaptists under "Intolerable Articles Concerning the Church" with the statement: "That Christ did not receive His body and blood from the Virgin Mary, but brought them with Him from heaven." The body of Täuferakten, most of which have been published, must be examined to determine to what extent these views were actually represented among the Middle and South German Anabaptists if at all. There is no evidence of it among any of the numerous Hutterite documents.

The early Anabaptist confessions of faith and writings of the Low Countries emphasize this teaching strongly. The public debates between the Reformed and the Anabaptists of Emden (1578) and Leeuwarden (1596) cover it in great detail. During the 17th century some of the more liberal groups began to give up this doctrine and it thus became one of the first typical Dutch Mennonite characteristics to be dropped. However, the fact that the Catalogus (181-184) lists more than two dozen writings ou this subject printed during this century indicates that this was by no means a dead issue in the Dutch brotherhood at this time. When S. F. Rues visited the Dutch Mennonites during the first half of the 18th century, only the conservative groups such as the Old Flemish and the Danzigers were still adhering unitedly to this doctrine (Rues, Aufrichtige Nachrichten, 16), while the progressive Mennonites had given up Menno's view and agreed in this matter with the rest of Christendom (p. 97). The Lammerenkrijgh and other influences had overshadowed this teaching, and its significance in connection with the attempt to establish a true church "without spot or wrinkle" had been lost sight of. However, such books as the Old Flemish Onderwyzing des Christelyken Geloofs ... by Pieter Boudewyns of 1743, still strongly emphasized this view. This book was reprinted as late as 1825. By 1800 this peculiar view, with a few exceptions, had been forgotten as a "Mennonite doctrine." A complete study of this doctrine and its later development in Holland and other countries (such as Prussia) has not yet been made. -- Cornelius Krahn

See also Formula of Concord, Frankenthal Disputation

1990 Article

The responses to Jesus' question "Who do you say that I am" have been decisive for Christian faith and witness ever since Peter's first answer that Jesus is the Messiah (Matthew 16:16 and parallels). In many additional ways and with a rich variety of images and concepts, the New Testament recounts, testifies, describes, and teaches who Jesus is, what he has done, and what he shall yet do.

Since New Testament times, Christian churches have usually summarized this variety by speaking about both the divinity and the humanity of Jesus Christ (his person) and about what he has already done and will yet do for the salvation of human beings and the renewal of creation (his work). Christology addresses both major concerns. It thus seeks to articulate, in a disciplined way, a coherent and comprehensive account of the person and work of Jesus Christ for the church's life and witness, an account which is based on the Scriptures, learns from the church's teachings through the centuries, and meets the contemporary challenges to confessing him as Savior and Lord.

Because of its fundamental importance, Christology has been a focus of intense concern as well as controversy in church history. Especially from the 2nd through the 7th century, the churches hammered out basic formulations (dogmas) meant to establish guidelines for orthodox teaching and guard against heretical doctrines about the person of Jesus Christ. They sought to correct views which overemphasized his divinity at the expense of his humanity (sometimes called Docetism) or his humanity at the expense of his divinity (sometimes called adoptionism). Particularly the creeds of Nicaea (325) and Chalcedon (451) have been seen as foundational references for orthodox doctrine.

Throughout the centuries there has been less dogmatic unanimity about the work of Christ. Mainstream Western orthodox theology has generally adopted some form of the "satisfaction" view originally associated with Anselm of Canterbury (11th century). Other major views of the atonement have included the "moral influence" theory, originally elaborated by Peter Abelard (12th century), and the classical or "victory over the powers" motif, most popular in western Christianity from the 2nd through the 7th century, and revived more recently in revised forms.

Prior to the 19th century, Protestant theology generally adopted traditional Western Christian christological views. In addition, it placed great emphasis upon the Christian's appropriation of Christ's benefits through faith, rather than through a sacramental system (ordinances). And particularly in the Calvinist tradition, Protestant orthodoxy elaborated an understanding of Christ's work according to his threefold prophetic, priestly, and kingly "office."

Sixteenth-century Anabaptist and Mennonite Christologies were generally compatible with orthodox understandings in the sense that they affirmed both the divinity and humanity of Jesus Christ and salvation through his atoning death on the cross. However, they usually couched these affirmations in selected biblical categories and made little constructive use of the traditional dogmatic vocabulary. This preference for biblical terms has had both positive and problematic consequences for Mennonite theology and ethics since the 16th century.

On the positive side, this preference contributed to the Anabaptist and Mennonite teaching about Jesus as the model and example for believers. While affirming his divinity they also emphasized Jesus' humanity, teaching, and actions. While teaching his atoning work on the cross, they also emphasized Jesus' way of the cross as the model for Christian discipleship. These emphases had tended to recede into the shadows of orthodox Christology since the controversies of earlier centuries. To be sure, Protestants and Roman Catholics also found ways of considering Jesus Christ normative for Christian life. But these ways fit predominantly within the patterns of Constantinian Christendom. For the Anabaptists and Mennonites, following Jesus Christ and his teaching in life resulted in an alternative pattern of Christian and church life.

On the problematic side, this preference contributed to some deviations from traditional orthodoxy as well as from scriptural balance and most likely contradicted either one or both. These included the "heavenly flesh" teaching, adopted by Menno Simons and Dirk Philips largely from Melchior Hoffman's apocalypticism, and the Logos Christology represented especially by Hans Denck.

Menno and Dirk asserted that Jesus' humanity (flesh) was nourished in Mary, but that it originated in heaven and did not receive its substance from Mary. They based this position partly on John 6 and 1 Corinthians 15, and partly on the Aristotelian view that the mother's seed is entirely passive. By emphasizing that Jesus' humanity came down from heaven in the Incarnation as an entirely new creation, they intended to support their distinctive views on salvation and the church. Through faith in the new Adam descended from heaven, human beings can be born anew and recreated to a new state of obedience. And this new creation manifests itself in the church without spot and wrinkle, the new community of those who are reborn and separated from the sinful world, having cast aside the weapons of violence and war.

The heavenly flesh doctrine became a major point of controversy between Mennonites and Protestants as well as between several Mennonite and Anabaptist groups in the 16th and into the early 17th century. Some maintained it until the middle of the 18th century. But it may have influenced some Mennonite concepts of church, salvation, and Christian ethics considerably longer, perhaps even until the present. The concept of the pure church, linked originally with the heavenly flesh Christology, has most likely contributed to both perfectionism and divisions among Anabaptists and Mennonites throughout their history.

In terms of traditional dogma the celestial-flesh Christology emphasizes the divinity of Jesus Christ at the expense of his humanity. It has therefore been accused of being gnostic in the sense of assuming that matter and spirit are irreconcilable. It has also been considered docetic. Contemporary scholars differ in their assessments: the Melchiorite-Mennonite teaching is docetic (Klaassen in Classics of the Radical Reformation 3), has docetic tendencies (Beachy), cannot be adequately described as docetic (Voolstra), or is not docetic (Keeney). Judgments differ along a similar scale on whether it is basically gnostic, has gnostic tendencies, or does not fall into gnosticism.

Denck's Christology has been markedly less influential. As are other areas of his thought, Denck's Christology is complex and difficult to categorize. Nonetheless, it had a mystical and universalizing tendency. It focused on the incarnate Word more than on the incarnate Christ. The eternal or inner Word suffered not only in the incarnate Lamb Jesus Christ, but had also suffered before and suffers since in the elect. Similarly, the eternal Logos which was victorious in Jesus Christ, has been victorious in the elect from the beginning and shall be so until the end.

This Logos Christology provides the basis for the theology of the divine in every human. Although the humanity as well as the divinity of Jesus is important for Denck, the two natures seem to remain somewhat separated from each other. The historical Jesus or the outer Word is important primarily as the teacher and example, namely, as the witness to the inner Word, which provides the means of deification for the disciple. Denck emphasized the unity of Christ's will with God's will, and the freedom of the will to be one with God. Some of his followers found his synthesis difficult to maintain and seriously questioned orthodox Christological and trinitarian doctrines.

Another Anabaptist theologian and church leader during the 16th century was Pilgram Marpeck. His influence at the time may have almost equaled that of Menno Simons. Although he shared an interest in relating Christology to the concepts of salvation and the church, he rejected the heavenly flesh Christology and articulated a distinctive view of Christ's humanity and its relation to his divinity.

Marpeck developed his views on the humanity of Christ partly as correctives to Lutheran and spiritualist (Schwenckfeld) Christologies. At the heart of Marpeck's thought is his view of the unity between the divine and the human natures in Jesus Christ. The essence (wesen) of reality is the unity between its inner and the outer dimensions. In Jesus Christ, the human (outer) serves the divine (inner). Simultaneously, the human (outer) also makes the divine (inner) visible and corresponds to it. In parallel fashion, the church as the visible and nonglorified body of Christ is enabled and called to correspond to the glorified and reigning Christ, who is the head of the body. Marpeck also extended this structure of thought to Christian discipleship, the sacraments, Christian liberty, and anthropology.

Contemporary scholars have devoted little attention to christological developments among Mennonites from the 17th through the 19th centuries. During that time, Mennonite confessions of faith generally perpetuated non-dogmatic views of Christ's person and work, which they nevertheless gradually adapted to traditional orthodox and Protestant concepts. This tendency is most pronounced in the major 20th-century North American Mennonite confessions from the early 1920s through the mid-1970s. These confessions have also been influenced by Fundamentalist and conservative reactions to modernism, reactions that emphasized Christ's divinity and sacrificial atonement and tended toward doceticism. Simultaneously, Mennonites have continued to preach and teach that Jesus Christ exemplifies how Christians are called to live. This has both tempered the Fundamentalist and traditional orthodox influences and opened Mennonites to modern christological views which begin with the historical Jesus, emphasize his humanity and ethical significance, and frequently have adoptionist tendencies.

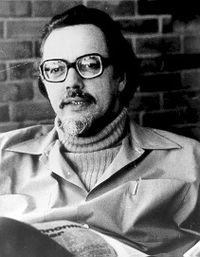

A representative voice for the conservative view tempered with a non-dogmatic biblicism and Jesus as the example for Christian discipleship was J. C. Wenger. He generally adopted traditional orthodox and Protestant views on Jesus Christ's humanity and divinity and his three-fold office as the framework for interpreting New Testament Christology. Wenger summarized several biblical concepts for the atonement rather than attempting to develop a comprehensive synthesis. He also accepted several affirmations of conservative Christologies, including the preexistence, the virgin birth, the sacrificial death, and the bodily return of Jesus Christ. Wenger assumed the bodily resurrection without mentioning it in his account of Christology. His concept of discipleship appeared not to imply any basic modifications of traditional christological assumptions, but belonged to an understanding of Christian life and holy living. This included an emphasis on nonresistance and nonconformity.

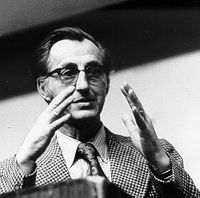

The most influential book related to Christology by a 20th-century Mennonite theologian to date is likely John Howard Yoder's The Politics of Jesus, which has been translated into several languages since the mid-1970s. In contrast to Wenger, it adopted current emphases on Jesus' humanity and his ethical significance. Yoder first put forth its major thesis in the context of conversations between the historic peace churches and mainstream Protestants in the late 1950s (Puidoux Conferences). It sought to correct traditional theological ways of avoiding the pacifist content of Scriptures and rejected modern systematic divisions between the Jesus of faith and the real Jesus.

For Yoder, Jesus' life, his calling of an alternative community, teaching, and crucifixion revealed and incarnated a qualitatively new possibility of human, social, and political relations. Jesus' life, calling of alternative community, teaching, and crucifixion therefore remain normative for Christian social ethics. Although Yoder did not attempt to construct a comprehensive Christology, he claimed to take Chalcedon's affirmation of Jesus' humanity more seriously than mainstream theologies which circumvent biblical pacifism and the way of the cross. In other writings, Yoder emphasized Jesus' lordship and affirmed that the ordinariness of Jesus' humanness and crucifixion, as well as his resurrection, demonstrates the general application of Jesus' work of reconciliation. Simultaneously, he criticized theological and ethical approaches which limit the distinctiveness of Jesus, discipleship, and the church entirely to modern historicist and moral categories.

More than any other Mennonite author, Gordon Kaufman has attempted to reformulate theology from an historicist perspective. Rather than beginning with a conservative framework for Mennonite concerns like Wenger or with the christological foundations for Christian pacifism in a biblical realist and Barthian vein like Yoder, Kaufman comes to Christology from modernist systematic and epistemological considerations and grounds Christology in an understanding of the humanness of Jesus compatible with critical New Testament scholarship and contemporary historicism (the view that all of reality is essentially historical rather than based on supernatural, transcendent reality).

Kaufman therefore fundamentally reformulates most christological concepts. Instead of focusing upon the person of Christ as the unity of divine and human natures, he speaks about Jesus as the Servant, the Word, and the Son understood in historical-personal terms. Instead of adopting any traditional view of the atonement, he interprets the Christ-event as having established a community of authentic love and thus inaugurating a historical process which is transforming human existence into God's kingdom. Instead of the resurrection referring to an experienced event, it is a theological interpretation of Christ's appearances and means that God is Lord of history regardless of what human beings may do. Instead of the virgin birth being a touchstone for the doctrine of the incarnation, it represents a crude attempt to express the belief that Jesus is God's Son.

The most recent (1980s) christological proposals from Mennonite theologians are being made by John Driver, Thomas Finger, and C. Norman Kraus. Finger reconstructs theology by adopting an eschatological orientation for the entire range of doctrine. Within this perspective, he understands Christ as the fulfillment of the promise of God's righteousness. He then develops a Christology around the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, rather than with traditional dogmatic categories.

Driver has focused on the work of Christ. His radical evangelical approach to the doctrine of atonement has arisen in the context of cross-cultural mission (in Spain and Latin America) seeking to disengage itself from the Constantinian assumptions of traditional theories and to do justice to the multiple biblical images of the atonement. Driver discovers even more biblical concepts for the atonement than Wenger and suggests that they reflect the contexts in which the early church carried out the missionary mandate of its Lord. Rather than reducing the multiple biblical images to one system, Driver recommends using them to enrich the understanding of the entire work of Christ. This pluralism of motifs also means that the saving work of Christ includes his ministry, his resurrection, and the actualizing power of the Spirit, its well as his death.

Kraus may be the first North American Mennonite theologian who attempts to construct, as an alternative to conservative as well as liberal Protestant approaches, a comprehensive Christology from a modern reinterpretation of Anabaptism. Like Driver, Kraus' approach has also been influenced by cross-cultural mission (in Japan). He contends that Christology in a historical and social-psychological mode best reflects the biblical and Anabaptist understandings of Jesus Christ and fits a missionary theology.

Kraus replaces the traditional metaphysical concepts of person and work of Jesus Christ with the identity and mission of Jesus, the Messiah. The identity of Jesus is described in terms of the man Jesus, the Son of the Father and the Self- Disclosure of God. Kraus's account of Jesus' mission focuses on how Jesus as Lord overcomes sin with love by having taken the way of the cross, on salvation as the renewal of the image of God, and on the appropriation of salvation through Jesus' identification with us and our solidarity with him. In contrast to Western theological emphases on salvation from guilt, Kraus argues that reconciliation to God through the cross of Christ deals with shame as well as with guilt.

Driver and Kraus thus contribute cross-cultural mission concerns to current christological discussions. In addition to such attempts to address Christology from a missionary stance, contemporary Mennonite teaching, preaching, and piety reflect both diverse motifs, and some common interests. The diversity ranges from classical orthodox views filtered through pietist and evangelical lenses to modern images seen in historical and social perspectives. The common interests focus on discipleship and the community which confesses Jesus as the Christ. Some 16th century Anabaptists couched these common interests in terms vulnerable to Docetism. Some contemporary Mennonites express them in categories vulnerable to adoptionism. Christology therefore remains at the center of both doctrinal and ethical, as well as soteriological and ecclesiological discussion and debate, both among Mennonites and between Mennonite and other Christians. -- Marlin E. Miller

See also Judaism and Jews; Sciences, Natural

Bibliography

Beachy, Alvin J. The Concept of Grace in the Radical Reformation. Nieuwkoop: B. de Graaf, 1977: 79-86, 178.

Blough, Neal. Christologie Anabaptiste: Pilgram Marpeck et l'humanite du Christ. Genève: Labor et Fides, 1984; cf. Mennonite Quarterly Review 61 (1987): 203-212.

Brons, A. Ursprung, Entwickelung und Schicksale der .. . Mennoniten. Amsterdam, 1912: 97 ff.

Brown, Mitchell. "Jesus: Messiah Not God." Conrad Grebel Review 5 (1987): 233-52, with responses Conrad Grebel Review (1988): 65-71.

Burkhart, I. E. "Menno Simons on the Incarnation." Mennonite Quarterly Review 4 (1930): 113-139, 178-207; 6 (1932): 122-123.

The Complete Writings of Menno Simons, c. 1496-1561, trans. Leonard Verduin, ed. J. C. Wenger. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1956.

Cramer, Samuel and Fredrik Pijper. Bibliotheca Reformatoria Neerlandica, 10 vols. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1903-1914: V, 125-170, 210-214. Vols. 1-6 available in full electronic text at http://www.archive.org/search.php?query=Bibliotheca%20Reformatoria%20Neerlandica.

Dorner, A. Entwicklungsgeschichte der Lehre von der Person Christi II. Berlin, 1853: 637-643.

Driver, John. Understanding the Atonement for the Mission of the Church. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 1986.

Finger, Thomas N. Christian Theology: an Eschatological Approach. Nashville: Thomas Nelson Sons, 1985; Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 1985.

Finger, Thomas N. "The Way to Nicea: Some Reflections From a Mennonite Perspective." Journal of Ecumenical Studies 24 (1987): 212-31; cf. Conrad Grebel Review 3 (1985): 231-249.

Hege, Christian. Die Täufer in der Kurpfalz. Frankfurt, 1908: 124 f.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. III, 113-115.

Hulshof, A. Geschiedenis van de Doopsgezinden te Straatsburg. Amsterdam, 1905.

Horsch, John. Menno Simons. Scottdale, PA, 1916.

Kaufman, Edmund G. Basic Christian Convictions. North Newton: Bethel College, 1972: 125-63.

Kaufman, Gordon D. Systematic Theology: a Historicist Perspective. New York: Scribner's, 1978.

Kawerau, Peter. Melchior Hoffman als religiöser Denker. Haarlem, 1954.

Keeney, William E. The Development of Dutch Anabaptist Thought and Practice From 1539-1564. Nieuwkoop: B. de Graaf, 1968: 89-113, 191-221.

Keeney, William E. "The Incarnation: a Central Theological Concept in A Legacy of Faith, ed. C. J. Dyck. Newton, KS: Faith and Life, 1962: 55-68

Klassen, Walter, ed. Anabaptism in Outline: Selected Primary Sources. Classics of the Radical Reformation, 3. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1981: 23-40.

Krahn, Cornelius. Menno Simons. Karlsruhe, 1936.

Kraus, C. Norman. Jesus Christ our Lord: Christology From a Disciple's Perspective. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1987.

Krebs, Manfred. Quellen zur Geschichte der Täufer. IV. Band, Baden and Pfalz. Gütersloh: C. Bertelsmann, 1951.

Leendertz, W. J. Melchior Hofmann. Haarlem, 1883.

Leith, John H. Leith, editor. Creeds of the Churches: a Reader in Christian Doctrine From the Bible to the Present. Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1977, with confessional and creedal statements, including New Testament, Protestant and Roman Catholic, Anabaptist and Mennonite.

Loewen, Howard John, ed. One Lord, One Church, One Hope, One God: Mennonite Confessions of Faith. Text-Reader Series, 2. Elkhart, IN: Institute of Mennonite Studies, 1985.

Oosterbaan, J. S. "Een doperse Christologies, Nederlands Theologisch Tijdschrift 35 (1981): 32-47.

Philips, Dirk. Bibliotheca Reformatoria Neerlandica, Cramer, Samuel and Fredrik Pijper, eds. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1903-1914: v. X, 135-153.

Schoeps, H. J. Vom himmlischen Fleisch Christi. Tübingen, 1951.

Schwenckfeld, Caspar. Corpus Schwenckfeldianorum. Leipzig : Breitkopf & Haertel, 1907-1961: vols. V, VI, VII.

Voolstra, Sjouke. Het woord is vlees geworden: de Mechioritisch-Menninste incarnatieleer. Kampen: Uit Geversinaatschaappij J. H. Kok, 1982; cf. idem, "The Word has become flesh, the Melchiorite-Mennonite teaching on the incarnation," Mennonite Quarterly Review 57 (1983): 155-60.

Weaver, J. Denny. "A Believers' Church Christology." Mennonite Quarterly Review 57 (April 1983): 112-31.

Weaver, J. Denny. "The Work of Christ: on the Difficulty of Identifying an Anabaptist Perspective." Mennonite Quarterly Review 59 (1995): 107-29.

Wenger, John C. Introduction to Theology. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 1954: 62-70, 193-211, 334-59.

Yoder, John Howard. The Politics of Jesus. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1972.

Yoder, John Howard. "But We Do See Jesus: the Particularity of Incarnation and the Universality of Truth." in The Priestly Kingdom. Notre Dame: U. of Notre Dame Press, 1984: 46-62.

Zur Linder, F. O. Melchior Hofmann. Leiden, 1885.

| Author(s) | Cornelius Krahn |

|---|---|

| Marlin E. Miller | |

| Date Published | 1989 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Krahn, Cornelius and Marlin E. Miller. "Christology." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1989. Web. 3 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Christology&oldid=122147.

APA style

Krahn, Cornelius and Marlin E. Miller. (1989). Christology. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 3 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Christology&oldid=122147.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 3, pp. 18-20; vol. 5, pp. 147-150. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.