Difference between revisions of "North Holland (Netherlands)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m (Text replace - "date=1957|a1_last=van der Zijpp|a1_first=Nanne" to "date=1957|a1_last=Zijpp|a1_first=Nanne van der") |

m (Text replace - "<em>.</em>" to ".") |

||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

<hr/> | <hr/> | ||

= Bibliography = | = Bibliography = | ||

| − | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. <em>Mennonitisches Lexikon, </em>4 vols | + | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. <em>Mennonitisches Lexikon, </em>4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. III, 272-275. |

{{GAMEO_footer|hp=Vol. 3, pp. 918-920|date=1957|a1_last=Zijpp|a1_first=Nanne van der|a2_last= |a2_first= }} | {{GAMEO_footer|hp=Vol. 3, pp. 918-920|date=1957|a1_last=Zijpp|a1_first=Nanne van der|a2_last= |a2_first= }} | ||

Revision as of 20:40, 13 April 2014

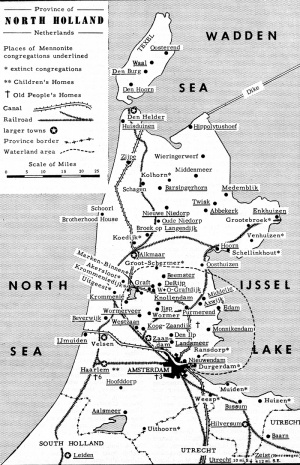

North Holland (Dutch, Noord-Holland) is a province of the Netherlands between the North Sea and IJssel Lake (formerly Zuiderzee). It has an area 1,016.4 square miles, and its population in 1947 was 774,273, with 28,492 Mennonites. In 2006 the population was 2.6 million. In the Reformation period the area was smaller, but much land has been reclaimed since 1564, including Beemster Lake under the direction of J. A. Leeghwater 1610-1614, Purmer 1622, Wormer 1626, Schermer 1632-1635, and Haarlem Lake 1848-52. Since the 16th century many fertile polder have been created; in 1597 Zijpe, 1610 Wieringerwaard, 1847 Anna Paulovnapolder, 1932 Wieringermeerpolder. Many Mennonites settled on these new lands as farmers. The province of North Holland in its present form dates from 1813. Formerly the boundary was formed by the IJ, and during the 17th and 18th centuries the southern part with the cities of Amsterdam and Haarlem belonged to South Holland rather than North Holland. In the following account the present status is understood.

The earliest traces of Anabaptists in North Holland are found about 1530; in that year Jan Volkertsz Trypmaker founded the congregation in Amsterdam; Melchior Hoffman baptized probably 50 persons here in 1531; and Anabaptists are also found in other places. Especially in 1533-1534 the number increased rapidly. In Amsterdam 100 baptisms were performed on some days. In Monnikendam two-thirds of the population was "contaminated," and in Westzaan about 200 persons were baptized in the winter of 1533-1534.

Now the government began its violent measures of suppression and put many to death. Nevertheless the movement grew in strength. In this province, where the Anabaptists were more numerous than in any other Dutch province, the spirit of Münster was evident, but not dominant. To be sure, about 3,000 persons crossed the Zuiderzee on the way to Münster on 24 March 1534, following the call of Jan van Leyden, but these people were not revolutionaries. They were seized at the Bergklooster in Overijssel. Among them were many wealthy persons. The Anabaptist preachers above all rejected violence, as is seen in a ministerial conference held in Spaarndam near Haarlem in late 1534 or early 1535. The small following of Münster in North Holland is seen in the fact that Jan van Geelen, the emissary from Münster, in his attempt to storm the Amsterdam city hall (10 May 1535), actually had only elements from other places at his disposal, and also from the fact that the procurator of the Court of Holland needed only a small number of soldiers for his ruthless persecution. The Anabaptist movement was not eradicated by his raids in 1534 nor by the severe edict of 10 June 1535, which was aimed principally at the Anabaptists.

The Anabaptists remained numerous in North Holland and began to organize congregations. Menno Simons also was influential here. Jan Claesz of Alkmaar, who had some of Menno's books printed in Antwerp, and had distributed 600 copies of them, was executed for this deed in 1544. In 1556 Menno again visited North Holland. The elder Leenaert Bouwens baptized many here. When the outstanding elders, Menno, Bouwens, and Dirk Philips, adopted a stricter application of the ban, many congregations of North Holland were unable to follow their lead and adhered to the more lenient application. These were then known as the Waterlanders because they lived in the area called Waterland (between the IJ River and Hoorn); they were always the most influential and largest Mennonite branch in the province. They differed from the other groups by their individual piety, not considering their own group to be the only true church; they were also less negative to the world and to culture. But the other groups were also found in the province; especially in Haarlem and Amsterdam there were important congregations of the Flemish branch. A considerable number of Frisians were found particularly at Hoorn and Alkmaar.

In North Holland many difficulties remained even after the Spanish had been expelled (about 1580) and the government was in Reformed hands, though there were not so many difficulties as in the other provinces.

Concerning the oath, the States-General decided that the Mennonites were to be excused from it in favor of a simple assertion. Regarding marriage it was decided in 1580 that Mennonites must report their marriages to the magistrate or the Reformed pastor. In 1606 marriage within one's own congregation was approved, provided the government was informed of the event. This regulation became the general practice but many difficulties arose in this connection. On the whole the Mennonites were excused from bearing arms, while on their part the Mennonites did all they could to support the government in other ways. Donations of money were repeatedly made. In 1673 the rural churches of North Holland alone raised 30,000 guilders besides clothing and bedding. The strict practice of nonresistance was abandoned. Especially among the Waterlanders it was repeatedly charged in the first half of the 17th century that their merchant ships were furnished with guns to protect them against pirates. Among the stricter branches, however, the principle was held throughout the century and well into the next, though it may have been more theory than practice.

In the early days there was opposition to holding government office, but by 1581 a change was becoming evident among the Waterlanders; in a conference held in that year it was decided that holding minor offices was permissible, provided there was no bloodshed connected with them. In the communities where the Mennonites were in the majority, when they were elected to the offices of bailiff or even mayor, they were permitted to withdraw from the office upon payment of a fine, which was, however, seldom paid. Nevertheless many Waterlanders held important administrative offices in the first half of the 17th century. Until the 18th century the Frisians retained their aversion toward holding government office.

The Mennonites were not recognized by the government; they were merely tolerated. This was the theory; the practice was different. Although there were occasional difficulties regarding marriage, inheritance, and the building of churches, the government protected these citizens, who were of such benefit to the welfare of the country. Thus the magistrate of Amsterdam took their part when the British government refused to give them money due them on the ground that they would not swear to their rights of possession. Again the Amsterdam government in 1642 took steps to aid the oppressed Mennonites in Switzerland. It was also the lenient attitude of the government that prevented the Reformed from undertaking suppressive steps. When the Reformed pastor in 1597 wanted to hold a public debate with Lubbert Gerritsz, the government forbade it. But when it was a question of Socinianism, the government sometimes interfered. In 1626 Jacques Outerman, preacher at Haarlem, and in 1663 Galenus Abrahamsz de Haan had to answer for their teachings at court. The testimony of both was accepted. No wonder that the Dutch Mennonites rejoiced in this privilege; Hans Vlamingh, a Mennonite merchant of Amsterdam, wrote to a friend in Switzerland in 1659, that the Mennonites there were permitted to meet freely, sometimes 2,000 at one time and place, that in Amsterdam and elsewhere they had orphanages and almshouses, free of taxation, that they could perform their ordinances free of molestation; the government accepted their word instead of the oath; they were citizens like anybody else, but exempt from war and military service, for which they paid a certain tax.

The Mennonites were important in the cultural life of North Holland. Famous poets and painters in the Golden Age were Mennonites or of Mennonite descent or were associated with Mennonites. Many were engaged in commerce, thus contributing greatly to the economic prosperity of Amsterdam and Haarlem. The Zaan River region, now an important industrial district, owes its prosperity largely to its Mennonite merchants and manufacturers. Also in shipping and deep sea fishing the Mennonites played a significant part.

The consequence of this was a great prosperity and increasing luxury; the dangers therein were pointed out on many occasions. Galenus Abrahamsz de Haan complained about the decline of the brotherhood. The complaint was certainly not unfounded. Not only in luxurious living did the changing spirit of the Mennonites express itself. The Mennonites no longer stood outside a world that they considered entirely evil; spiritually, too, contacts had been established with others. There was frequent connection with the Collegiants; yet there was also a large proportion of Mennonites who did not favor this connection, and this difference caused strife in many congregations, Waterlander as well as Flemish.

Another indication of the change in spirit was the fact that in many places the branches began to unite in the 18th century. It is therefore so much the more lamentable that a new division took place in 1664 at Amsterdam between the Lamists and the Zonists, which split the congregation into two camps.

The 18th century was a time of decay; many congregations declined rapidly in numbers, especially those around the Zuiderzee, which bloomed in the Baltic trade and nearly perished in its decline. Edam dropped from 80 to 12 members in the 18th century; in Hoorn, where there were four congregations, the total membership dropped from 450 to less than 100. But other congregations also showed a decrease; Amsterdam from more than 2,300 (about 1700) to 1,385 in 1832, Haarlem from 3,000 in 1708 to 485 in 1834.

Twenty small congregations in North Holland died out. Some were combined with others. Many had no preacher in the first half of the 18th century. The various conferences (Sociëteit) performed a good work: the Waterlander or Rijper Sociëteit, which must have been organized in the first half of the 17th century, though there is no record of it before 1694; the Frisian Sociëteit of North Holland, which was in existence in 1639 and merged with the Rijper Sociëëteit in 1844; the Zonist Sociëteit, which met from 1674 to 1796, and the South Holland or Lamist Sociëteit, which initiated the founding of the Mennonite seminary in Amsterdam, but soon disappeared from the scene. These conferences preserved many a congregation from extinction by looking after the preaching needs.

The organizing of the Algemene Doopsgezinde Sociëteit was also of great significance in North Holland. All the congregations could gradually be provided with educated preachers, and many received financial support. In the 19th century no congregations died out. Still the membership decreased here and there, and rarely did the membership keep pace with the increase in the population. Only in Amsterdam and Haarlem did the rate of increase exceed the rate of increase in the population. In the Gooi district a new congregation was organized at Bussum in 1915; in Hilversum the old Huizen congregation was revived. Also in Ifmuiden, a rapidly rising town on the locks of the North Sea canal, there has been a Mennonite congregation since 1909. The Haarlemmermeer congregation dates from 1950; and in the Wieringermeer, reclaimed from the former Zuiderzee, there is now also a congregation. According to the official Dutch census the number of Mennonites (including children) in the province of North Holland was 15,713 in 1849, 26,508 in 1900, and 28,492 in 1947. The baptized membership numbered 5,052 in 1771, 7,800 in 1847, 11,332 in 1900, and 17,722 in 1957.

For a view of the membership of the congregations in Holland, see the table in the article The Netherlands.

Bibliography

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. III, 272-275.

| Author(s) | Nanne van der Zijpp |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1957 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Zijpp, Nanne van der. "North Holland (Netherlands)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1957. Web. 22 Nov 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=North_Holland_(Netherlands)&oldid=120782.

APA style

Zijpp, Nanne van der. (1957). North Holland (Netherlands). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 22 November 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=North_Holland_(Netherlands)&oldid=120782.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 3, pp. 918-920. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.