Difference between revisions of "Alternative Service Work Camps (Canada)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

SamSteiner (talk | contribs) (wikified table) |

AlfRedekopp (talk | contribs) ("the Indians" replaced by "the Indigenous") |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

The increasing problem of dependency had also been a factor in bringing about the new program of gradual withdrawal of the men from the camps and their individual assignments to farms and factories. Under the new arrangement, farmers paid conscientious objectors $25 per month plus room and board. The rest of the wages were turned over to the Canadian Red Cross. Those working in factories or where the employers could not supply maintenance were given $38 a month in addition and the balance was given to the Red Cross. Up to June 1944 over $300,000 had been contributed to the Red Cross under this plan. In addition, a varying scale of $10 to $20 a month was provided for dependents. Compensation laws covered all men. If the Alternative Service officer approved, the cost of medical emergencies could be subtracted from the Red Cross contributions. The men in the camps, however, continued receiving only 50 cents a day plus board, lodging, compensation insurance, and medical and dental care. Dependents of men in camp, however, could receive help from the provinces or municipalities in which they resided. If such help was given, the Ministry of Labour reimbursed the government unit making the payment. | The increasing problem of dependency had also been a factor in bringing about the new program of gradual withdrawal of the men from the camps and their individual assignments to farms and factories. Under the new arrangement, farmers paid conscientious objectors $25 per month plus room and board. The rest of the wages were turned over to the Canadian Red Cross. Those working in factories or where the employers could not supply maintenance were given $38 a month in addition and the balance was given to the Red Cross. Up to June 1944 over $300,000 had been contributed to the Red Cross under this plan. In addition, a varying scale of $10 to $20 a month was provided for dependents. Compensation laws covered all men. If the Alternative Service officer approved, the cost of medical emergencies could be subtracted from the Red Cross contributions. The men in the camps, however, continued receiving only 50 cents a day plus board, lodging, compensation insurance, and medical and dental care. Dependents of men in camp, however, could receive help from the provinces or municipalities in which they resided. If such help was given, the Ministry of Labour reimbursed the government unit making the payment. | ||

| − | The men who were assigned to their own farms were under the control of the Alternative Service officer regarding working conditions, assignments, transfers, dismissals, and wages. In theory men could have been assigned to defence plants or also to foreign service, teaching, or social service. The government, although interested in placing each man where he could contribute most to the nation, took his preference into account. Only a few were placed in teaching positions among the | + | The men who were assigned to their own farms were under the control of the Alternative Service officer regarding working conditions, assignments, transfers, dismissals, and wages. In theory men could have been assigned to defence plants or also to foreign service, teaching, or social service. The government, although interested in placing each man where he could contribute most to the nation, took his preference into account. Only a few were placed in teaching positions among the Indigenous, Japanese, and Eskimos, where public sentiment did not prevent them from serving. |

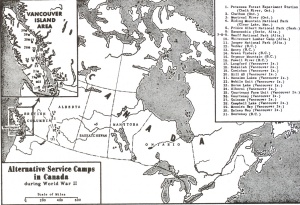

[[File:ME1_606_large.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Alternative Service Work Camps | [[File:ME1_606_large.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Alternative Service Work Camps | ||

Latest revision as of 16:43, 26 January 2023

In June 1941 the Canadian government informed the Committee on Military Problems of the Conference of Historic Peace Churches (Ontario) that alternative service was to be provided for conscientious objectors (COs) to war. The conscientious objectors were to serve for four months in Alternative Service camps operated by the Department of Mines and Resources. Later the time of service was extended for the duration of the war. The government agreed to provide maintenance and traveling expenses to and from camp, and to pay the men 50 cents a day. The churches were also allowed to appoint religious advisers.

The first camp was located at Montreal River, 625 miles northwest of Toronto and 83 miles northwest of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, at the point where the Montreal River empties into Lake Superior. The place had formerly been a lumber camp. The first campers arrived there in July 1941, and during the first summer there were as many as 165 there at one time. J. Harold Sherk served as the religious adviser of the camp, but during the winter Harold D. Groh substituted for a three-month period. The Department of Highways employed the men to construct the joining link of the Trans-Canada route. Most of the men worked in the gravel pits or at clearing the bushlands.

In May 1942 the British Columbia Forest Service concluded an agreement with the Dominion Government to give alternative service work to hundreds of conscientious objectors. Their work was to consist of snag falling, road building, erecting telephone lines, fire fighting, and reforestation. Under the arrangement the Dominion Government paid the Forest Service $2.50 per day per man. Of this amount, the camper was paid 50 cents and the rest was used to take care of his board, lodging, and medical attention. The lease expired with the end of the government year but it was renewed for a twelve-month period, as the military authorities feared a bombing of the West Coast that might produce a forest fire hazard.

In the spring of 1942, forestry camps were opened in British Columbia, and during the summer the men from Camp Montreal River were transferred west to the new camps. The Beacon, which was the mimeographed publication carrying news from the British Columbia camps, listed 19 camps for the province in July 1943. Fourteen of these were on Vancouver Island and five on the mainland in western British Columbia. They were designated by such terms as C-1, Q-3, and GT-5 but also carried names such as Hill 60 camp, Campbell Lake camp, and Seymour Mountain camp. A camp engaged in road building was located in Saskatchewan.

By April 1943, 17 of the British Columbia camps were working on forest protection and two on national park projects. Five national park camps were operated in Alberta, one in Saskatchewan, and one in Manitoba. The national park camps were under the Department of Mines and Resources. Two camps in Ontario under this department, the Montreal River camp and the Chalk River camp, were, however, engaged in highway construction.

At the same time, a shortage of farm labor developed in Canada. The Beacon reported in April 1943 that in the previous autumn a sizable portion of the Alberta harvest had remained in the fields because of the shortage of farm labor. An Order in Council effective 1 May 1943 transferred the Alternative Service System from the Canadian Selective Service System and military control to the Ministry of Labor, a civilian agency, and opened the way for the use of conscientious objectors on farms and in factories.

The increasing problem of dependency had also been a factor in bringing about the new program of gradual withdrawal of the men from the camps and their individual assignments to farms and factories. Under the new arrangement, farmers paid conscientious objectors $25 per month plus room and board. The rest of the wages were turned over to the Canadian Red Cross. Those working in factories or where the employers could not supply maintenance were given $38 a month in addition and the balance was given to the Red Cross. Up to June 1944 over $300,000 had been contributed to the Red Cross under this plan. In addition, a varying scale of $10 to $20 a month was provided for dependents. Compensation laws covered all men. If the Alternative Service officer approved, the cost of medical emergencies could be subtracted from the Red Cross contributions. The men in the camps, however, continued receiving only 50 cents a day plus board, lodging, compensation insurance, and medical and dental care. Dependents of men in camp, however, could receive help from the provinces or municipalities in which they resided. If such help was given, the Ministry of Labour reimbursed the government unit making the payment.

The men who were assigned to their own farms were under the control of the Alternative Service officer regarding working conditions, assignments, transfers, dismissals, and wages. In theory men could have been assigned to defence plants or also to foreign service, teaching, or social service. The government, although interested in placing each man where he could contribute most to the nation, took his preference into account. Only a few were placed in teaching positions among the Indigenous, Japanese, and Eskimos, where public sentiment did not prevent them from serving.

Whenever men were placed on farms or in industry, a contract was made. When the first contracts expired in 1944, the chairman and secretary of the Mennonite Military Problems Committee in Ontario were asked to spend eleven days sitting with the Alternative Service officials in Division A reviewing and renewing the contracts. Later the two men attended eight regional meetings in Division B. In both areas they brought up problems and grievances that might have received no consideration had they not been present. In spite of these safeguards the contracts differed in many details, as seemed necessary in the judgment of the Alternative Service officers. This lack of equality among conscientious objectors often led to dissatisfaction, but an attempt was made by the Mennonite Military Problems Committee in Ontario to explain the differing contracts and to show the people how difficult it was to obtain perfect justice for everyone in a war period.

A chief Alternative Service officer administered the Alternative Service program, with headquarters in Ottawa. There were 13 mobilization districts in the Dominion, each with an Alternative Service officer and a staff of eight or more persons. In 1944 and 1945 those men between the ages of 18 and 38 were registered, but men were not called up until they had reached 18.5 years of age.

When a medical notice was received from the Mobilization Board, the man reported to a doctor for a physical examination. Within eight days after the notice for a physical examination was received, the man filled in an application signed by his pastor, requesting a conscientious objector status. This was sent to the Mobilization Board. Mennonites of the 1874-80 migration and Dukhobors were given automatic postponement as conscientious objectors upon certification by their pastors or leaders. After the Mobilization Board declared a man to be a conscientious objector, they presented the name to the district Alternative Service officer, who then placed the man in a camp, in a factory, or on a farm. The officer, after investigating the needs of the man and the job he was to be given, used his discretion in drawing up a suitable contract, which provided for the wages and other compensations mentioned above as well as the regular payments to the Canadian Red Cross.

After the Ministry of Labour took charge of the conscientious objectors, a decreasing number were sent to the camps. In March 1944 the British Columbia Forest Service camps were closed and the men sent back to their home provinces where they were placed in agriculture or industry. Other camps were closed, too, so that by June 1944 only seven remained. These were Chalk River, Ontario; Riding Mountain, Manitoba; Banff and Seebe, Alberta; Radium Hot Springs, British Columbia; a small road camp in Saskatchewan; and the Montreal River camp.

Most of the men in camps at the late date were those who had refused the work assigned them or had refused work of any kind. They were sentenced to the camps in a Magistrate's Court and taken to the camps by police escort. There was possibility of appealing the decision of any of the 13 Mobilization Boards. The boards had the privilege of calling upon the justice of the peace of a man's home community to interview him when they questioned his sincerity, but when they denied him his conscientious objector status there was nothing he could do. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police escorted these men to the military barracks, where the army attempted to persuade them to accept military service. When they refused, they were given one, two, or three fourteen-day courts-martial in the guardhouse. "In the majority of these cases, the military authorities recommend to the Mobilization Boards that these men be given the status of postponed Conscientious Objectors. Official figures indicate that about 300 men have been involved in this group during the five years that Canada has been at war." Most these 300 were Jehovah's Witnesses.

In the early spring of 1945, there were approximately 6,000 conscientious objectors under contract in Canada. A report as of 31 March 1944, stated that there were 8,932 conscientious objectors that were given postponement of military service in Canada. "Of these, 245 have offered their services in the armed forces and 122 have volunteered as noncombatants in the medical and dental corps. Of the others, 3,188 were placed in agriculture and 1,295 in other employment."

A table in Erfahrungen der Mennoniten in Canada während des zweiten Weltkrieges lists the following number of conscientious objectors for all of Canada during the entire war:

Prince Edward Island |

3

|

Nova Scotia |

29

|

New Brunswick |

2

|

Quebec |

28

|

Ontario |

2,602

|

Manitoba |

2,948

|

Saskatchewan |

2,320

|

Alberta |

1,157

|

British Columbia |

1,611

|

Total |

10,700

|

Of the approximately 9,000 in March 1944, about 2,000 were Dukhobors. Of the total, approximately 63 per cent were Mennonites, 20 per cent Dukhobors, 10 per cent Plymouth Brethren, Christadelphians, and Pentecostal groups, and three per cent Jehovah's Witnesses. A partial list of churches represented in the camps included 30 denominations. Manitoba, the home of thousands of Russian Mennonites and Dukhobors, furnished the largest number of objectors of all of the Canadian provinces.

On 15 August 1946 the government of Canada revoked the Order in Council P.C. 3030 and all COs returned to civilian life. Up to that date over 5,000 young Mennonite men of Canada had been classed as conscientious objectors and had served in camps or in other areas under a system of conscription. What effect had this experience upon them? J. W. Nickel, a young Canadian Mennonite minister who preached in many of their camps, declared that camp life among other results "taught those, who because of previous isolated church life held the members of another denomination in narrow esteem, to respect and love their brother."

Bibliography

Dyck, John M. Faith under test: alternative service during World War II in the U.S. and Canada. Mountridge, KS: Gospel Publishers ; Ste. Anne, MB: Gospel Publishers, 1997.

Gingerich, Melvin. Service for Peace: A History of Mennonite Civilian Public Service. Akron, Pa.: Mennonite Central Committee, 1949.

Klassen, A. J., ed. Alternative service for peace: in Canada during World War II 1941- 1946. Abbotsford, B.C.: MCC (B.C.) Seniors for Peace, 1998.

Klassen, John C. Alternative service memoirs. Morden, MB: John C. Klassen, Jake Krueger, 1995.

Nickel, J. W. "The Canadian Conscientious Objector." Mennonite Life (Jan. 1948): 24-28.

Reimer, David P. Erfahrungen der Mennoniten in Canada während des zweiten Weltkrieges, 1939-1945. Steinbach, Man., 1948.

Storms, P. L. "Forest Service in B. C. Service Work Camps." Christian Monitor (Oct. 1943).

Toews, John A. Alternative service in Canada during World War II. Canadian Conference of the Mennonite Brethren Church, [1959].

Additional Information

Web site: Alternative Service in the Second World War: Conscientious Objectors in Canada 1939-1945.

| Author(s) | Melvin Gingerich |

|---|---|

| Date Published | March 2009 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Gingerich, Melvin. "Alternative Service Work Camps (Canada)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. March 2009. Web. 3 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Alternative_Service_Work_Camps_(Canada)&oldid=174673.

APA style

Gingerich, Melvin. (March 2009). Alternative Service Work Camps (Canada). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 3 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Alternative_Service_Work_Camps_(Canada)&oldid=174673.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, pp. 76-78. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.