Difference between revisions of "Bullinger, Heinrich (1504-1575)"

| [unchecked revision] | [checked revision] |

GameoAdmin (talk | contribs) (CSV import - 20130820) |

m (Text replace - "<em>Mennonitisches Lexikon</em>, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. I," to "''Mennonitisches Lexikon'', 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. I,") |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

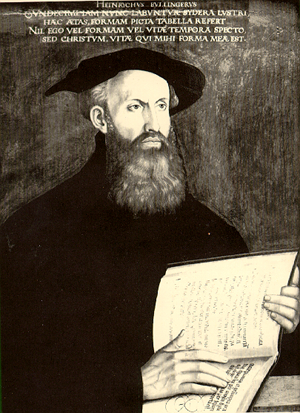

| − | [[File:Heinrich-Bullinger.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Heinrich Bullinger. Source: | + | [[File:Heinrich-Bullinger.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Heinrich Bullinger. <br /> |

| + | Source: [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Heinrich_Bullinger.jpg Wikipedia Commons]'']] | ||

| − | + | Heinrich Bullinger, chief pastor of the Reformed Church in [[Zürich (Switzerland)|Zürich]], [[Switzerland|Switzerland]], was born 18 July 1504, at Bremgarten in [[Aargau (Switzerland)|Aargau]]. He was educated under humanistic influence in [[Cologne (Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany)|Cologne]]. After serving his home church as pastor for two years, he withdrew from papal activities, on the urging of his friends, and fled to Zürich, where he was offered [[Zwingli, Ulrich (1484-1531)|Zwingli's]] position after his death in 1531. In his position of chief pastor of Zürich, which he held until his death in 1575, he developed the plans laid by Zwingli for the newly established Reformed Church into a firm structure. His influence extended far beyond Switzerland, over [[Italy|Italy]], [[Netherlands|Holland]], France, [[England|England]], [[Bohemia (Czech Republic)|Bohemia]], Transylvania, [[Hungary|Hungary]], and [[Poland|Poland]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

Bullinger's first contact with the [[Swiss Brethren|Swiss Brethren]], according to his diary, occurred at the disputation in Zürich on 17 January 1525. He says briefly, "Amazing is the impertinence of the [[Anabaptism|Anabaptists]]," but wrote a few tracts dealing with the topics under discussion. It was his especial mission to insure the existence of his church and secure it everywhere by a definite, systematic, and foresighted attack on the Swiss Brethren. His public attitude toward them is shown in the following writings: | Bullinger's first contact with the [[Swiss Brethren|Swiss Brethren]], according to his diary, occurred at the disputation in Zürich on 17 January 1525. He says briefly, "Amazing is the impertinence of the [[Anabaptism|Anabaptists]]," but wrote a few tracts dealing with the topics under discussion. It was his especial mission to insure the existence of his church and secure it everywhere by a definite, systematic, and foresighted attack on the Swiss Brethren. His public attitude toward them is shown in the following writings: | ||

| Line 47: | Line 46: | ||

Füssli, Johann Conrad. <em>Beyträge zur Erläuterung der Kirchen-Reformations-Geschichten des Schweitzerlandes ..., </em>5 vols. Zuerich: bey Conrad Orell und Comp., 1741-1753: v. III, 190-201 | Füssli, Johann Conrad. <em>Beyträge zur Erläuterung der Kirchen-Reformations-Geschichten des Schweitzerlandes ..., </em>5 vols. Zuerich: bey Conrad Orell und Comp., 1741-1753: v. III, 190-201 | ||

| − | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. | + | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. ''Mennonitisches Lexikon'', 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. I, 291-298. |

Paulus, N. "Heinrich Bullinger und seine Toleranzideen." <em>Historisches Jahrbuch </em>26 (1905): 576-587. | Paulus, N. "Heinrich Bullinger und seine Toleranzideen." <em>Historisches Jahrbuch </em>26 (1905): 576-587. | ||

Latest revision as of 00:03, 16 January 2017

Heinrich Bullinger, chief pastor of the Reformed Church in Zürich, Switzerland, was born 18 July 1504, at Bremgarten in Aargau. He was educated under humanistic influence in Cologne. After serving his home church as pastor for two years, he withdrew from papal activities, on the urging of his friends, and fled to Zürich, where he was offered Zwingli's position after his death in 1531. In his position of chief pastor of Zürich, which he held until his death in 1575, he developed the plans laid by Zwingli for the newly established Reformed Church into a firm structure. His influence extended far beyond Switzerland, over Italy, Holland, France, England, Bohemia, Transylvania, Hungary, and Poland.

Bullinger's first contact with the Swiss Brethren, according to his diary, occurred at the disputation in Zürich on 17 January 1525. He says briefly, "Amazing is the impertinence of the Anabaptists," but wrote a few tracts dealing with the topics under discussion. It was his especial mission to insure the existence of his church and secure it everywhere by a definite, systematic, and foresighted attack on the Swiss Brethren. His public attitude toward them is shown in the following writings:

- Von dem unverschampten fräfel, ergerlichem verwyrren unnd unwarhafftem leeren der selbsgesandten Widertöuffern, vier gespräch Bücher, zu verwarnenn den einfalten, Durch Heinrychen Bullinger geschriebenn. Een guter bericht vonn Zinsen. Ouch ein schöne underwysung von Zähenden (Zürich, 1531, 178 leaves).

- Bedenken der Herren Gelehrten zu Zürich, welches dieselbigen A. 1535, dem Rate daselbst der Wiedertäufer halben übergeben (1535, reprinted in Füsslin III, 190-201).

- Der Widertoufferen Vrsprung, fürgang, secten, wäsen, fürnemme vnd gemeine jrer leer artickel, ouch jre gründ und warumb sy sich absünderind, vnnd ein eigne kirchen anrichtind, mit widerlegung vnd antwort vff alle und yede jre gründ und artickel, sampt Christenlichem bericht vnd vermanen, dass sy jres irrthumbs und absünderens abstandind, und sich mit der kirchen Christi vereinigind, abgeteilt in VI Bücher, und beschriben durch Heynrichen Bullingern . . . (Zürich, 1560, 2d. ed. in 1561, title above).

- A long letter to Egli in Chur, of 13 October 1570. (State archives of Zürich, E. II, 342, 606; reprinted in Korrespondenz Bullingers mit den Graubündnern III, 221 ff.)

Von dem unverschampten frävel is an earnest effort to refute in a book intended for popular consumption the basic tenets of the Anabaptists. It was much in demand by those who had to deal with the "hazard" of Anabaptism. It provides us with a summary of what Bullinger considered to be the main doctrines and emphases of the Swiss Brethren, together with his attempted refutation. It appeared in a Dutch edition in 1569.

In the early 1530s the Anabaptist movement definitely receded, the government grew more lenient, and the Diet of the four cities in 1533 advised milder measures. But the Münster affair became the occasion for sharper procedure. In Bern a persecution broke out, so that many Anabaptists fled to Zürich territory and forced the council of Zürich to take a position. In this connection the "opinion of the scholars" of 1535 was drawn up under the influence of Bullinger (printed in full in Füssli, Beyträge III, 190-201). This document is a justification and a statement of reasons for the procedure of the authorities against the Anabaptists as a sect, and their Scriptural punishment. It is significant that this statement deals in detail with the question of faith as a gift of God, for as long as this question was not decided a remnant of doubt remained in the minds of not only the lower classes against the church, which might be of advantage to the Anabaptists. Their attitude toward Anabaptist doctrine was more or less determined by the nature of their conception of faith. Furthermore, it was important to protect the young church from the charge that in the persecution of dissenters they were no better than the Catholic Church, and the seriousness of the question may have caused many to be concerned with the content of faith—as is clearly seen in a letter from Haller to Bucer—rather than to harmonize it with the demands of the time through a historical or dogmatic interpretation. In the Bedenken the authors (namely, the Zürich clergy) limit themselves to refuting the Anabaptist concept by citing the Old Testament and delimiting the idea of faith as a "free" gift as they understood it. By demonstrating that Anabaptists were a sect, they also justified their punishment, without having been guilty of wrongdoing. A classification of the sects according to the enormity of their error, the distinctions between the various degrees, is for the most part written with the Anabaptists in mind, even though it speaks of sectarians in general and only at the end mentions the Anabaptists and condemns them on the basis of the well-known consequences of "common Anabaptist doctrine" (contempt for the sacraments, disturbance of the peace, refusal of obedience to the government, etc.). The only new point presented is the form of Anabaptist trials, since the question of infant baptism merely led to evasions and only an examination in all the Articles would lead to more definite results. Nevertheless the attitude toward the Anabaptists had changed in that each deviating opinion was no longer punished with death, but that "individuals should be punished according to the degree of deviation and the receptivity for the church concept, according to the state of the affair and divine, temporal, and imperial law," i.e., to the death penalty.

The Bedenken specified the directions for dealing with the Anabaptists and was strictly observed. The Anabaptists replied by mass emigrations to Moravia.

The 1540s and 1550s gave Bullinger little opportunity to express himself against the Anabaptists. Their activities only rarely extended beyond their own brotherhood. The development of church discipline and conformation of their manner of life to the requirements of the Sermon on the Mount remained their principal objective and were in the 1560s the nucleus to which the populace attached itself and called a new movement into being.

It would be possible to connect this new movement with Bullinger's history, Der Wiedertöufferen Ursprung, published in 1560, and explain it as the second refutation of the Anabaptists in his own country. But this is not actually the case, as is indicated in a letter to Fabricius. Bullinger writes on 8 December 1559 that he is fully occupied by a German book contra anabaptistarum sectas omnes, long requested by many North Germans, for the "Anabaptist pest" was particularly strong in those regions. He had to make a thorough revision of the four books he wrote 29 years before, and finished the first in two weeks, so that it could be publicized at the next market (Frankfurt Frühjahrsmesse). That the Wiedertöufferen Ursprung was in part based on his earlier polemic, Von dem unverschampten frävel (1531), and that it was a hasty revision, is of significance. It reveals once again Bullinger's impression of the Anabaptists over a three-decade span of time. In the eyes of Bullinger there were but two churches, Reformed and Catholic; the Anabaptists were not a church but a sect.

This point of view recognizing only two churches is even more obvious in Bullinger's practical work, as his letters to the Poles show, in which he recommends the suppression of the least expression of opinion contrary to the dogmas of the church.

The principle peculiar to the Anabaptists, viz., that the church does not have the authority to proceed with force against matters of conscience, found supporters even in the ranks of leading clergymen (Gantner in Chur; see letters of Bullinger to Egli in Korrespondenz mit den Graubündnern, pp. 1565-70 ff.). With all the means at his disposal Bullinger, through Egli, the parson in Chur, seeks to keep the Reformed Church pure and free of subjective expressions of opinion.

In a letter of 3 October 1570 to Egli, Bullinger for the last time carries on a theoretical argument with the Anabaptists; nothing essential is added to his previous views. He proceeds from the consequences of Anabaptist doctrine and even in questions of minor importance he looks for Anabaptist suggestions which he stamps as Areally seditious . . . articles"; even the mere charge that Gantner wants to treat the Anabaptists more leniently elicits the statement, "this article stinks of sedition."

Tolerance toward the Anabaptists can be spoken of only in a very limited sense, since Bullinger thinks that they as sectarians cannot demand it. His words to Faber, "We do not exercise force against those who do not adhere to our faith; for faith is a free gift of God, which cannot be forced; therefore faith can be neither bidden nor forbidden," obviously have reference only to divergencies within the evangelical church (and to the Catholic creed). He was able to avoid the attempt, resulting from the decline of the church at the end of the 16th century, to accept the Anabaptist principles of church order, for at this time church and state were still more closely connected, so that no further forms were required within the church to preserve order. Until the end he was a determined opponent of the Anabaptist movement.

He is largely responsible for the theory that the Zürich Anabaptists got their views from Thomas Müntzer, a view which H. S. Bender completely refuted in his Conrad Grebel, 110-119, where he traces the development of Bullinger's theory on this point.

Bibliography

Bender, Harold S. Conrad Grebel, c. 1498-1526: the founder of the Swiss Brethren sometimes called Anabaptists.Goshen, IN: Mennonite Historical Society, 1950.

Bergmann, Cornelius. Die Täuferbewegung im Kanton Zürich bis 1660. Leipzig: M. Heinsius Nachf., 1916.

Bullinger, Heinrich. Heinrich Bullingers Diarium (Annales vitae) der Jahre 1504-1574: zum 400. Geburtstag Bullingers am 18. Juli 1904. Hrsg. von Emil Egli. Basel: Basler Buch- und Antiquariats-Handlung, 1904.

Bullinger, Heinrich. Heinrich Bullingers Reformationsgeschichte. Frauenfeld: Beyel, 1838-1840.

Bullinger, Heinrich. Von demm unverschampten fraefel, ergerlichem verwyrren unnd unwarhafftem leeren der selbsgesandten widertöuffern vier gespräch Bücher ... Ein guter bericht vonn Zinsen ; Ouch ein schöne underwysung von Zähenden. Zürich, 1531.

Bullinger, Heinrich. Der Widertöufferen Ursprung, Fürgang, Secten, Wäsen, fürnemme und gemeine irer Leer Artickel ... Zürich: Froschower, 1560. Reprinted Leipzig : Zentralantiquartiat der DDR, 1975.

Egli, Emil. Die St. Galler Täufer: geschildert im Rahmen der städtischen Reformationsgeschichte. Zürich: Schulthess, 1887.

Egli, Emil. Die Züricher Wiedertäufer zur Refomationszeit: nach den Quellen des Staatsarchivs. Zürich: Friedrich Schulthess, 1878.

Egli, Emil and R. Schoch, Johannes Kesslers Sabbata mit kleineren Schriften und Briefen. St. Gallen: Fehr'sche Buchhandlung, 1902.

Füssli, Johann Conrad. Beyträge zur Erläuterung der Kirchen-Reformations-Geschichten des Schweitzerlandes ..., 5 vols. Zuerich: bey Conrad Orell und Comp., 1741-1753: v. III, 190-201

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. I, 291-298.

Paulus, N. "Heinrich Bullinger und seine Toleranzideen." Historisches Jahrbuch 26 (1905): 576-587.

Schiess, Traugott. Bullingers Korrespondenz mit den Graubündnern 1533-1575. Basel: Verlag der Basler Buch- und Antiquariatshandlung, 1904-1906.

Schulthess-Rechberg, Gustav von. Heinrich Bullinger, der Nachfolger Zwinglis. Halle: Verein für Reformationsgeschichte, 1904.

Wotschke, Theodor. Der Briefwechsel der Schweizer mit den Polen. Leipzig: M. Heinsius, 1908.

Wuhrmann, Willy. Register zu Heinrich Bullingers Reformationsgeschichte. Zürich, 1913.

| Author(s) | Cornelius Bergmann |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1953 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Bergmann, Cornelius. "Bullinger, Heinrich (1504-1575)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1953. Web. 21 Nov 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Bullinger,_Heinrich_(1504-1575)&oldid=144904.

APA style

Bergmann, Cornelius. (1953). Bullinger, Heinrich (1504-1575). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 21 November 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Bullinger,_Heinrich_(1504-1575)&oldid=144904.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, pp. 467-468. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.