Difference between revisions of "Philipp I, Landgrave of Hesse (1504-1567)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m (Added hyperlinks.) |

m |

||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

Wappler, Paul. <em>Die Täuferbewegung in Thüringen von 1526-1584</em>. Jena: Gustav Fisher, 1913. | Wappler, Paul. <em>Die Täuferbewegung in Thüringen von 1526-1584</em>. Jena: Gustav Fisher, 1913. | ||

{{GAMEO_footer|hp=Vol. 4, pp. 163-166|date=April 2007|a1_last=Neff|a1_first=Christian|a2_last=Thiessen|a2_first=Richard D.}} | {{GAMEO_footer|hp=Vol. 4, pp. 163-166|date=April 2007|a1_last=Neff|a1_first=Christian|a2_last=Thiessen|a2_first=Richard D.}} | ||

| + | [[Category:Persons]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Rulers and Politicians]] | ||

Revision as of 04:34, 23 January 2014

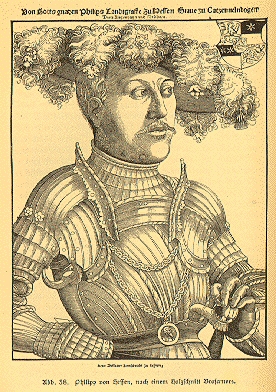

Philipp I der Großmütige (Philip the Magnanimous): Landgrave of Hesse (Landgraf von Hessen), 1509-1567; born 13 November 1504. He was the son of Landgrave Wilhelm II of Hesse (1469-1509), who died when Philipp was only five years old. Until 1518 Philipp was under the regency of his mother Anna of Mecklenburg (1485-1525). Philipp introduced the Reformation into Hesse in 1526, founded the University of Marburg in 1527, and was one of the most zealous promoters of the Reformation in Germany.

In his attitude toward the Anabaptists he showed extraordinary generosity and kindness. He saw in the Anabaptist movement a disorder in religious life, which had its roots in error and weakness in the faith rather than in moral error like sedition and revolt, and which must therefore be treated with lenience and consideration. Characteristic of his attitude are his words: "I see more improvement of conduct among those whom we call fanatics than among those who are Lutheran" (a letter to his sister, Duchess Elizabeth of Saxony, 18 February 1530). "On every hand there is no perfect faith in us, so that we must say: Lord, I believe; help Thou mine unbelief" (Heidenhain, 78). "Alas, how cold love is among us who call ourselves Christian and those who create such offense must give an account before God and bear a grievous judgment" (Corpus Reformatorum IX, 762). Above all, he said, one must try to lead them back to the church by persuasion and indoctrination. Expulsion from the country was the severest penalty he would permit; it too must be preceded by teaching. Bishop Franz of Münster asked his advice concerning the punishment of the Anabaptists (letter of 20 January 1534; Cornelius, p. 218), as did also Karl, Margrave of Baden (letter of 12 October 1566). Philipp replied, informing him of the decrees that had been issued against the Anabaptists: "not to follow them too strictly, but always deal according to the circumstances and persons, so that the poor people might be converted and brought to the truth" (Hochhut, 554; Franz, No. 150).

At first Philipp felt compelled to take steps against Melchior Rinck. In 1528 Philipp had a personal talk with him in the hunting castle Friedewald near Hersfeld (Wappler, II, 53). Then Philipp made repeated attempts, but vain, to have him converted by the pastor Balthasar Raidt and the theologians at the University of Marburg. Now Rinck was sentenced to church penance, but remained in the country. Therefore Johann, Elector of Saxony, sent Philipp the printed and manuscript writings of Rinck in order to induce him to take a more rigorous attitude. Soon afterward Rinck was seized on Hessian soil; but the efforts of the elector and his councillors to have a severe punishment inflicted were unavailing. Philipp repudiated all interference in this affair. Finally he made up his mind to banish Rinck from Hesse and Saxony, and to extract from him a vow never to return to either of the two principalities. This was done in May 1531 (Franz, No. 5, 13a, 14a).

On the part of Saxony and especially of the Lutheran divines no effort was spared to make Philipp, whom they suspected of an open inclination toward Anabaptism, change his opinion and to make clear to him the danger in his present position. Justus Menius dedicated to him his libelous booklet, Der Wiedertäufer Lehre und Geheimnis aus heiliger Schrift widerlegt. Mit einer schönen Vorrede von Dr. Martin Luther (Wittenberg, 1530). But Philipp was not influenced by the polemic. In the matter of the punishment of the Anabaptists living in Eisenach and in the Hausbreitenbach district, which were under the joint jurisdiction of the two rulers, a serious difference of opinion arose. Johann of Saxony demanded the death penalty; Philipp refused to give his consent. At the Schmalkaldic Bundestag at Nordhausen early in December 1531 the matter came up for discussion. The delegates of Saxony demanded the death sentence on the basis of the imperial decree (1529); the Hessian delegates countered that their prince had scruples against putting them to death. If they could not be deflected from their belief by indoctrination, they should be punished by having their hearth fire extinguished. They would then emigrate of their own accord. At most their homes should be barricaded (see the regulation of Philipp on the subject of the Anabaptists at the end of 1531 in Wappler, I, 154, Franz, No. 15). The Nordhausen Bundestag (Franz, No. 18) also discussed the case of Melchior Rinck, who had been rearrested on 11 November 1531. Again in vain. Again several of Rinck's writings were sent to Philipp, as well as a personal letter from Johann dated 21 December 1531, which expressed the hope that the old revolutionary be punished with the sword, a course justifiable before God and with a good conscience. Johann called attention to the fact that the Hessian authorities had agreed to the death penalty in sanctioning the edict of Speyer on 23 April 1529. But Philipp was unable to inflict the death sentence on the obstinate Anabaptist. On 3 January 1532, he informed Johann that he had sentenced the Anabaptist leader to life imprisonment and had taken him to Burbach in the district of Katzenellenbogen, Wiesbaden area. He added that that he would not be able to reconcile his conscience to executing anyone with the sword in a matter of faith, where there was no other ground for taking his life. Otherwise no Catholics or Jews could be tolerated, for they blaspheme Christ to the highest degree, and would have to be put to death in a like manner (Franz, No. 17, 18b).

Philipp likewise refused to consent to the severe penalty for the Anabaptists arrested in Hausbreitenbach. Finally they were divided between Saxony and Hesse; some of the former were executed, the latter were released. In no indefinite terms he also rejected the idea of executing Fritz Erbe, who was imprisoned in Eisenach. To Elector Johann Friedrich of Saxony, who had demanded the death sentence for Erbe on the basis of the opinion of the Leipzig court, he declared in a letter of 22 May 1533, that he had never yet had a man put to death solely on a matter of belief; he had merely banished such or commanded them to sell their goods and move out. Only the obstinate who refused to go had he arrested. Therefore in the case of Fritz Erbe he also favored exile. If Erbe should refuse to leave the country he should be kept in prison until he changed his mind. He could not persuade himself "to punish anyone with the sword because of an error of faith, which is a gift of God, and was adopted at the time, not from malice, but from ignorance." He maintained this position in spite of repeated efforts by the elector, who based his opinion on the imperial law of 1529 and the official opinion of the theologians. Fritz Erbe remained in prison until his death in 1548 (Franz, No. 25).

In July 1533, when 18 Anabaptists were again seized in Hausbreitenbach and the Elector of Saxony again demanded their execution, Philipp refused with the words, "Our Lord will give grace that they may be converted." This hope of Philipp's was fulfilled in several instances in September of that year when some Anabaptists imprisoned in Mühlhausen recanted. After the revolt of 1525 the protectorate over the city of Mühlhausen was held in turn for a period of one year each by the Elector of Saxony, Duke Georg of Saxony, and Philipp of Hesse. On 15 June 1533, the rule fell to Philipp. He had a difficult position to maintain against the other two rulers. But he did not yield, and sent the pastor Raidt to Mühlhausen to convert the Anabaptists imprisoned there; Raidt was surprisingly successful in persuading all to recant, whereupon they were re-released (Wappler, II, 101). The Anabaptists at Sorga near Hersfeld were expelled in September 1533. They immigrated to Moravia (Wappler, II, 102; Franz, No. 28).

Philipp's position was made more difficult by the events at Münster. From the beginning he gave his attention to developments there. He corresponded with Bishop Franz von Waldeck and the regent and the city council (Cornelius, II); in a letter of 6 March 1535, he requested that the Anabaptists be watched (Becker, 83; Franz, No. 37). He sent his divines Theodor Fabricius and Johann Lening to Münster to convert the Anabaptists and to settle the dispute. After the fall of the city and the capture and condemnation of the leaders of this unfortunate movement, upon his express wish an attempt was made to convert the leaders by the Protestant clergymen Antonius Corvinus and Johann Kymeus. With some malicious satisfaction the Elector of Saxony made use of the opportunity to influence Philipp to take stronger measures against the Anabaptists. Already on 25 April 1534, he had called attention to the revolt in Münster as an example of the dangers of lenience. Philipp did not reply. He was obviously embarrassed. Expulsions from the country did no good. The Anabaptists kept returning. There were instances where they promised three times not to return, but still kept appearing. "In order not to undertake some thing so very burdensome as concerning the life and body against the Anabaptists," he requested the opinion (24 May 1536) of the magistrates of the cities of Strasbourg, Ulm, the dukes Ulrich of Württemberg and Ernst of Brunswick-Lüneburg, as well as of the theological faculties of the universities of Marburg and Wittenberg (Franz, No. 47).

Four days later he issued to all the districts of his realm a new mandate against the Anabaptists (Hochhut, 554-57; Franz, No. 47d). It is again unusually lenient for the times. It stipulates that the Anabaptists be summoned and diligently instructed by the clergy. If they persisted in their error they should be commanded to sell all their possessions within two weeks and leave the country with wife and children. If they promised this in a credible manner, they should be given all aid and support in the sale of their goods, "for we desire neither their lives nor their goods." But the houses of the disobedient should be barricaded, and no smoke or fire be allowed in them. Their property should be given them; they should only not live in the realm. All who granted them any aid were threatened with the same punishment as the Anabaptists. But those who were converted and returned to the church should be kindly received and only admonished to avoid "harm and disadvantage" in the future.

To discuss the opinions that were sent to Philipp, Philipp summoned the most prominent of his councilors, the knights, and his theologians, in addition to several representatives from the cities of his land to Kassel on 7 August 1536 (Becker, 84; Franz, No. 47 P.Q.). This point of time was extremely unfavorable for the Anabaptists. Shortly before, a band of robbers and arsonists posing as Anabaptists was seized and some of its members executed. So it came about that the Hessian chancellor Feige also expressed himself in favor of greater severity toward the Anabaptists. He wanted to have the death penalty inflicted at least on the foreign Anabaptists who returned the third time after as many expulsions; for it was necessary to be on one's guard against them. The sharpest opinions were expressed by the Lutheran preachers Tilmann Schnabel and Justus Winter, who demanded a strict enforcement of the imperial edicts, whereas their colleague Johann Lening, who had been Philipp's emissary to Münster, gave this judgment: "One should pray God to correct the errors in his own life and to admonish the Anabaptists kindly and in a friendly spirit. Even if all that they carry on their shield were bad, it is necessary to use caution and not make use of the sword until all other means have been tried."

A new regulation against the Anabaptists was worked out, which was with Philipp's consent adopted verbatim in the Hessian church inspection regulations of 1537 (see Hesse; Franz, No. 47 R.S.). It sharply insists on the abolition of vices, because the Anabaptists were offended by them. In general it contains a sharpening of the previous regulation: "Foreign preachers of Anabaptists shall be beaten with rods, have a sign burned into their cheeks, and be threatened with death if they ever returned." Natives were ordered to sell all their goods. But if they did not do this within the time set, their houses should be closed up, the hearth fire extinguished, and their goods sold. The proceeds should be kept until they demanded it, and they were to be ordered on penalty of death to leave the country forever. If foreigners should nevertheless return, criminal proceedings should be inaugurated against them and the law take its course according to the imperial mandates. Natives should, on the other hand, in this case be beaten with rods and a sign burned on their faces; if they returned again after this, they should be racked and executed. The same methods should be used against those who were ordered to leave the country but refused to do so. "But no Anabaptist shall be put to death, even after the sentence has been passed, without previously notifying us."

But if someone had not previously baptized, preached, or held meetings, and had perhaps been misled through lack of misunderstanding, but refused to receive instruction, he should, in case he was a foreigner, be expelled from the country for all time, for the first offense. If he should, however, return, he should be beaten with rods and have a sign burned on his cheek; on the third offense he should be put to death. But if he in the face of death recanted, he should be taken back for further consultation and not killed. These severe measures were never put into effect; Philipp never confirmed a death sentence. In 1540 he was able to write that in his realm the death sentence had never been inflicted on an Anabaptist. The Anabaptists were given gentle treatment. This was also true of those imprisoned in Wolkersdorf, Georg Schnabel and others. On them was found a letter from Peter Tasch with the address: "To the elect and called in the Lord, Jörgen S., my dear brother together with his companions among the wild beasts in tribulation and misery." This letter Philipp sent to the Elector of Saxony and the Duke of Jülich, Tasch's sovereign, and recommended to them that they keep a watchful eye on the Anabaptists. Since this letter also mentioned the Anabaptist movement in England, Philipp drew up a letter with the Elector of Saxony to Henry VIII, and sent it through the council of Hamburg, notifying him of the presence of the Anabaptists in England (Franz, No. 62).

Philipp took pains to induce the Anabaptists imprisoned in Wolkersdorf to recant. He sent them a letter in his own hand (Hochhut, 612; Franz, No. 76), expressing his disapproval of the lenience of their imprisonment; he would therefore have reason to deal otherwise with them, but did not wish to do so, but once more wanted to deal with them graciously and kindly, and was therefore sending them a God-fearing man who wanted to discuss with them in a friendly way their error; they should listen to him, give him good information; they would have to be obstinate indeed and remain stubbornly by their adopted opinion (if they refused to listen to him); "he shall show you the right way, so that you may come to the true knowledge of divine truth, which we would most heartily like to see and would rather hear than to proceed against you with rigor, as is our right, since you refuse to desist from your unchristian sect." To this end he called Martin Bucer, the reformer of Strasbourg, to Hesse (Philipp's letter to the magistrate of Strasbourg, 9 August 1538). This led to complete success. Peter Tasch and his followers declared themselves willing to submit to the church. They presented their modified principles in a document called Bekenntnis oder Antwort einiger Fragestücke oder Artikeln der gefangenen Täufer und anderer im Land zu Hessen vom 11. Dezember 1538 (Hochhut, 612-22; Franz, No. 85); the statement was accepted by the Lutheran clergy, who then declared that they were "willing to pardon those Anabaptists and accept them in the church." Eagerly Philipp accepted the proposal of Bucer to have these converts win their brethren. He did not hesitate to deal with them in person, and to his great joy most of the Anabaptists of his realm returned to the established church.

In 1544 there were once more negotiations between Saxony and Hesse concerning Anabaptists in the Hausbreitenbach district. Again Johann Friedrich wrote to Philipp (28 July 1544; Franz, No. 121), demanding that the imperial edict be enforced against the obstinate Anabaptists, who had had ten years to consider. If Philipp hesitated to do this, he should at least not hold it against Johann Friedrich if he (Johann Friedrich) punished them in accord with the imperial edict, which had been confirmed at the last Reichstag at Speyer. Again Philipp withheld his reply; his conscience prevented his consenting to the request. To the extreme annoyance of Justus Menius, the superintendent, the Anabaptists in Hausbreitenbach remained unpunished. Philipp also protected the Anabaptists in Mühlhausen, whereas Georg of Saxony had them cruelly put to death and the Elector of Saxony demanded the death penalty for them. In a writing to Johann Friederich on 19 August 1545, Philipp cited his general reasons and also the passages of Scripture, Matthew 13: 24-30; Luke 9:52-56; and Romans 14:1-5 and Romans 12 ff., and said, "These quotations block our path to such an extent that we cannot find it in our conscience to proceed with such rigor against a person who errs somewhat in the faith; for the person might accept instruction over night and desist from his error. Now if such a one should straightway be put to death by one of us, we are truly concerned that we may not be innocent of his blood. For if one were to execute all those who are not of our faith, how would the Papists, likewise the Jews, fare, who in this matter err as deeply or even deeper than the Anabaptists? Therefore it pleased us once more, wherever these people are, that they be arrested and indoctrinated by skilled persons with the Word of God; and those who would not return to the church and desist from their error after being instructed should be expelled from the country; if they returned or if they were so completely obstinate that they might infect others they should be kept in prison; the expenses would not be so great" (Franz, No. 128).

This letter is indeed evidence of a generous mind and noble religious tolerance, in which Philipp far surpassed his contemporaries and also the reformers Martin Luther and Philipp Melanchthon; he represented a new era, they were still in the clutches of the Middle Ages. He maintained this position even during his imprisonment by Charles V after the unfortunate outcome of the Schmalkaldian War. In his opinion to Johann Friedrich the Middle of Saxony, on 7 March 1559, he says, "It is so, many Anabaptists have an unchristian evil sect, as was shown at Münster and elsewhere; but they are not alike. Some are simple, pious folk; they should be dealt with in moderation. Anabaptists who deal with the sword may rightly also be punished with the sword. But those who err in faith should be dealt with leniently, and shall be instructed in accord with the principle of love to one's neighbor, and no effort shall be spared, also they shall be heard, and if they will not accept the truth and scatter error like a harmful seed among Christians, they shall be expelled and their preaching abolished. But to punish them with death, as happens in some countries, when they have done nothing more than err in faith and have not acted seditiously, cannot be reconciled with the Gospel. Other Christian teachers like Augustine and Chrysostom also violently opposed it."

This attitude Philipp also impressed upon his sons in his will: "To kill people for the reason that they believed an error we have never done, and wish to admonish our sons not to do so, for we consider that it is contrary to God, as is clearly shown in the Gospel" (Franz, No. 148). Philipp's sons and descendants held to this attitude. His spirit of gentleness and reconciliation lived on among them. "And it was due to this lenience toward the Anabaptists to a great extent, that new life and wholesome recollection of nearly forgotten truths of salvation were brought to the church" (Wappler, I, 117).

In spite of his zeal in promoting the Reformation throughout his lands, Philipp’s personal life was marred by a licentious lifestyle and a bigamous marriage. Philipp married Christine of Saxony (1505-1549), a daughter of Duke Georg of Saxony, in 1523, and they had 10 children between the years 1527 and 1547. However, in 1540 Philipp married Margarethe von der Saale and they had 9 children together between 1541 and 1558. Philipp argued with various Reformation leaders that because Scripture allowed men such as the Old Testament patriarchs to have more than one wife, he was therefore entitled to have two marriages as well. This situation led to a weakening of his relationships with other German Protestant princes.

Before his death on 31 March 1567, Philipp divided his lands among his four sons, Wilhelm IV, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel (1532-1592), Ludwig IV, Landgrave of Hesse-Marburg (1537-1604), Philipp II, Landgrave of Hesse-Rheinfels (1541-1583), and Georg I, Landgrave of Hesse-Darmstadt (1547-1596).

Bibliography

Becker, E. "Zur Geschichte der Wiedertäufer in Oberhessen." Archiv für hessische Geschichte und Altertumskunde, new series (periodicals), X (Darmstadt, 1914).

Cornelius, C. A. Die Geschichts-quellen des Bistums Münster. Münster, 1853: 218.

Egelhaaf, G. Landgraf Philipp der Grossmütige. Halle, 1904.

Festschrift zum Gedächtnis Philipps des Grossmütigen. Kassel, 1904.

Franz, Günther. Urkundliche Quellen zur hessischen Reformationsgeschichte. Vierter Band, Wiedertäuferakten 1527-1626. Marburg: N.G. Elwert, 1951.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. III, 363 ff.

Heidenhain, A. Die Unionspolitik Landgraf Philipps von Hessen 1557-62. Halle, 1890.

Hochhuth, K. W. H. "Landgraf Philipp und die Wiedertäufer." Zeitschrift für die historische Theologie XXVIII (1858): 538-644.

Hochhuth, K. W. H. "Landgraf Philipp und die Wiedertäufer." Zeitschrift für die historische Theologie XXIX (1859): 167-234.

Köhler, Walther. Urkundliche Quellen zur hessischen Reformations Geschichte I: 1182 ff.

Philipp der Grossmütige (Festschrift des Historischen Vereins für das Grossherzogtum Hessen, 1904).

Die Stellung Kursachsens und des Landgrafen Philipp von Hessen zur Täuferbewegung. Münster, 1910.

Wappler, Paul. Die Täuferbewegung in Thüringen von 1526-1584. Jena: Gustav Fisher, 1913.

| Author(s) | Christian Neff |

|---|---|

| Richard D. Thiessen | |

| Date Published | April 2007 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Neff, Christian and Richard D. Thiessen. "Philipp I, Landgrave of Hesse (1504-1567)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. April 2007. Web. 2 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Philipp_I,_Landgrave_of_Hesse_(1504-1567)&oldid=111562.

APA style

Neff, Christian and Richard D. Thiessen. (April 2007). Philipp I, Landgrave of Hesse (1504-1567). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 2 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Philipp_I,_Landgrave_of_Hesse_(1504-1567)&oldid=111562.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 4, pp. 163-166. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.