Java (Indonesia)

1959 Article

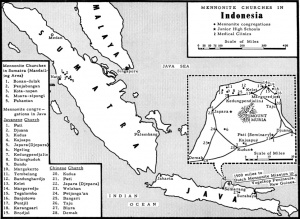

Java, the second largest island of Indonesia with 50,000 square miles and approximately 40 million inhabitants, in 1955 was the seat of a century-old Dutch Mennonite mission work and two organized Mennonite conferences. The island was divided into 23 districts, of which one of the smallest, Japara, lying on the north coast, was one of the most thickly populated, and was the center of the Mennonite work on the island. After June 1898 the Mennonite mission was the only mission in this territory since the Dutch Reformed mission turned over to the Mennonite board the stations of Pati and Kaju-Apu.

The Javanese people were almost exclusively Muslims. Originally they were Animists, but about the time of Christ they accepted Buddhism as their national religion. In the 13th century the first Muslim missionaries arrived and in a short time they had overthrown the Hindu religion. Though outwardly the Javanese people accepted Islam, in their real nature they remained Animists. In the mid-20th century they offered sacrifices to the spirits, whose number was reckoned at more than one thousand. The outward formality of Islam and its moral indifference correspond more with the Javanese character than the moral earnestness of Christianity. With their indifferent, somewhat dull character, and being given to the gross sins such as lying, stealing, and immorality, they were difficult to win for the Christian faith, which demanded a more earnest, moral manner of life. The missionaries had a hard task and secured fruits from their labors only slowly and after much difficult and sacrificial work.

After the Mennonite Mission Society in Amsterdam decided in 1847 to establish a mission in the Dutch East Indies, the first missionary, Pieter Jansz, sailed in August 1851 to Java. At first he located in Semarang, but in 1854 moved to Japara, a city which was not far from Semarang on the north coast. Jansz had earlier been prepared as a teacher and missionary by learning the Javanese and Malay languages and by studying the anthropology and culture of the Dutch East Indies. His work under the Mohammedan Javanese turned out to be very difficult. The first converts were baptized in 1854. In addition to preaching, he devoted himself to teaching the children of the natives. In 1856 a second missionary was sent out, H. C. Klinkert, who remained only a short time in Java. In 1857 Th. Doyer followed him, but died in 1861. Thereafter N. D. Schuurmans came out to the field in 1863 to work with Jansz. Schuurmans then took over the teaching work, while Jansz devoted himself to literary work, translating various writings into Javanese which were very useful in evangelization and teaching. In 1877, after 30 years of work, the church had only 39 members, and only 8 to 20 persons took part in the Sunday services. In 1875 the first stone school building was erected and five pupils of Schuurmans were at work as teachers in the neighborhood of Japara. In 1881 Jansz resigned from the mission field but remained in Java and translated the Bible into Javanese for the British and Foreign Bible Society. He died in 1904 at Kaju-Apu near Japara.

In 1878 P. A. Jansz, the son of Pieter Jansz, began a new epoch of work. He had come to the Netherlands in 1867, where he secured his license as a teacher in 1871, and was appointed missionary in 1878. He inaugurated new methods of work on the mission field, basing his work on the insight that the religious and economic life of the natives was very closely related. It was almost impossible for the Javanese to be Christians within the Muslim cultural pattern, so Jansz combined the development of new land for agriculture with evangelization. On 26 August 1881 he secured a tract of land in permanent possession (hereditary lease) for the yearly payment of 2 guilders per acre. This tract had 192 Javanese acres (one Javanese acre equals 1.9 American acres) and was later enlarged to 233 (433 U.S.) acres. The whole annual rental therefore was about 500 guilders. Jansz moved the congregation to this tract after he had established conditions which the settlers agreed to submit to. The chief requirements were the following: (1) only those who had good moral character would be accepted; (2) those who transgressed morally after acceptance would be expelled; (3) the smoking of opium as well as its ownership and sale were forbidden; (4) strong drink was also forbidden, both in use and in sale; (5) all idolatrous and superstitious practices had to be given up; (6) polygamy was forbidden, and gambling or similar practices would not be tolerated; (7) all inhabitants were obliged to attend the Sunday services faithfully, to send their children to school, and to observe Sunday as a rest day; (8) all inhabitants were to maintain their land, roads, bridges, and waterways themselves and pay regular contributions into the colony treasury; (9) the only requirement which they had to deliver to the government was a part of the rice harvest and a small annual cash payment for the land. Jansz had described these methods in a book entitled Evangelization Through Colonization in Java (Landontginning en Evangelisatie op Java, 1877). The first actual occupancy of the colony was in February 1881, which may be taken as the date of founding. The first colony (village) was given the name of Margaredjo, which means "the way to happiness." In 1901 a second colony was established with the name Margokerto, with 320 acres (608 U.S.). In 1910 a third colony was established with the name Bumiardjo, with 47 (89 U.S.) acres. And in 1925 another tract was secured with 197 (374 U.S.) acres, called Pakkies. These colonies became strong centers of Christianity in a Muslim land. They were the home base from which the neighboring villages could be evangelized.

Jansz devoted himself also with great consecration to teaching. When he began his work in 1878 the mission school had only 19 pupils. In 1932 the school program included a normal school, 5 intermediate schools, and 15 elementary schools, with a total of 1,264 pupils. In addition, there was established at Kudus a Chinese school with 151 pupils. A "seminary" for the training of native teachers was established at Margoredjo, which was given financial support by the government beginning in 1903, and in 1931 was designated as a normal school.

After 1878, additional missionaries were sent out to Java to work with Jansz. All of them, with the exception of a few Germans, were of Russian origin. Among them were Johann Fast who went out in 1888, Johann Hubert in 1893 (d. 1944), and Johann Klaassen in 1899 (died 1950), all from Russia. Daniel Amstutz from Switzerland served 1934-1946. Hermann Schmitt and Otto Stauffer, who served in 1929-1941, and Maria Klaassen, 1929-1950, were all from Germany. Schmitt and Stauffer died in 1942.

The Japara mission field was divided into four districts. (1) Kedung-Pendjalin, near Japara, was the location of the first congregation. To this district belonged the colonies of Margokerto and Pakkies. In 1932 the number of Christians in this territory was 627 adults with 649 children. (2) The second district was Margoredjo, together with Bumiardjo, with 1,203 Christians and 1,189 children in 1932. (3) The third was Kaju-Apu, a location which was taken over from the Rotterdam Reformed Missionary Society in 1899. In this district, with 159 Christians and 91 children in 1932, are also located the towns of Kudus (since 1929) and Pakkies. (4) The fourth district is Kelet, where the central hospital and the leper asylum of Donorodjo are located; it had 145 Christians and 94 children in 1932. The total of the four districts was 2,130 Christians and 2,023 children. The congregation of Margoredjo was made independent in 1928, with its own native preacher named Roebin.

A third new kind of mission work was medical missions. In 1894 a hospital was built at Margoredjo, and in 1902 another at Kedung-Pendjalin. Dr. H. Bervoets, who had been sent out in 1894 as the first missionary doctor in the service of the Dutch Missionary Society, was transferred to Java in 1908 and attached to the Mennonite Mission field. He was given by the government a tract of about 50 acres of oak forest lying between Margoredjo and Kedung-Pendjalin which he was allowed to use tax-free for the medical mission program. Kelet lies some 2,000 feet above the sea level and has a pleasant climate and much natural beauty. A hospital was built here which contained four halls and numerous apartments and side buildings including a school and a church. It also had a laboratory, a drug department, two operating rooms, and a darkroom. It had good equipment, including an X-ray. The hospital also served the leper colony of Donorodjo and maintained policlinics at Keling, Bangsri, Wedaridjaska, Taju, and Pati. The hospital itself had 50 beds and was normally staffed by 4 native helpers. In 1931 it had a total of 408 patients with 12,640 days of occupancy. At the Kedung-Pendjalin hospital there were 38 beds with 3 native helpers with a total in 1931 of 280 patients and 8,204 hospital occupancy days. In Kelet, the hospital had 367 beds, 2 European doctors, 2 European nurses, 64 native helpers, and in 1931 had 1,748 patients with 108,495 occupancy days.

The leper colony of Donorodjo was opened in 1916. It was established with the help of a considerable sum of money which had been collected in 1909 on the occasion of the birthday of Princess Juliana, from people living in the Dutch East Indies, and which was granted by the queen to be used for the leper work. The name Donorodjo actually means "gift of the princess." It was a leper village in which each leper had the free use of a piece of ground which he cultivated. The patients could establish their dwellings where they wished. They had their own coinage and a store in which everything could be purchased. They also had their own administration and their own organizations under their own leadership. There was here also a school and a church. The celebration of the Lord's Supper, in which many lepers were not able to take the bread in their own badly damaged hands, was a very impressive service. Donorodjo was always under the leadership of European directors.

The mission reached deep into the life of the natives. The appearance of a Christian village was very different from that of a Muslim village. An official report prepared under the direction of the Dutch Minister of Health and Welfare before 1931 reported five points in which the influence of the mission could be observed, and where it had reached very deeply into the life of the people. These were: housing and house furniture, clothing, cultivation of the fields, livestock, and payment of taxes and all financial obligations. In eleven other aspects of the life of the people various favorable results were noticed as the consequence of the influence of the mission, such as the establishment of permanent marriage relationships, the resistance to native fanatics, the elevation of womanhood, better teaching and attendance at the schools, more industriousness and economy, less spending of money for worthless purposes, less gambling and less use of opium, prostitution and polygamy, and more concern for the cultivation of gardens and fields. It was generally known that the native Christians had practically nothing to do with the police, that they always performed their obligations punctually whether financial or otherwise, that they remained in their locations permanently and therefore caused very little trouble to the authorities.

The financial support of the mission program included a subsidy from the government, which in 1928 amounted to approximately 35,000 guilders. The contributions to the mission treasury from the various Mennonite countries of Europe in that year were as follows: Holland 23,000 guilders, Germany 14,500 guilders, France and Switzerland together 2,000 guilders.

World War II led to catastrophe for the Dutch Mennonite Mission in Java. When the German army occupied the Netherlands in May 1940 contact with the congregations and missionaries in Java was broken. Two German missionaries, Hermann Schmitt and Otto Stauffer, were interned. After the Japanese attack on Indonesia in 1942 they were to be taken with other internees to Singapore. On the way the boat was torpedoed by a Japanese U-boat and both missionaries lost their lives. The remaining missionaries, Daniel Amstutz and Dr. K. P. C. A. Gramberg, reached an agreement with the Javanese Mennonite leaders that all the congregations should now become completely independent of the mission. In Kelet a union of Javanese Christian congregations in the Muria area was founded on 30 May 1940 with the name "Brotherhood of the Javanese Evangelical Christian Churches in the Vicinity of Pati, Kudus, and Japara," directed by a committee of five Javanese together with Amstutz and Gramberg. The eleven autonomous congregations later elected a synod for the general management of the church with Soehadiweka Djojodihardjo, the son of Sardjo Djojodihardjo, a former student at the University of Djahathas (Batavia) and pastor of the Pati congregation, as chairman. The church is founded on the Bible and the Apostles' Creed. Baptism upon confession of faith and the rejection of the oath, as well as congregational autonomy, were Mennonite characteristics. In November 1940 five competent Javanese preachers were ordained. Each congregation usually had an elder, several preachers, and several meeting places.

Supervision of the schools was made the responsibility of Sardjo Djojodihardjo, and the direction of the colonies was given over to Soemjar. In Donorodjo P. J. Bouwer was replaced as director by F. C. Heusdens, a missionary formerly in the Celebes. Since it was not possible to send money from the Netherlands, some financial support was given by Dutch Mennonites in Java and the Emergency Committee of the Reformed Mission in Batavia.

In 1942, when Java was occupied by Japan, terrible disorders broke out, especially in the Muria area. Fanatical Moslems waged a "holy war." They attempted to destroy all mission property and to compel all Christians to accept the Muslim religion. The mission hospital at Taju and the Gramberg home were completely destroyed, as were also the churches in Margoredjo and Tegalambo; several schools and churches were partly destroyed. The leper establishment at Donorodjo was plundered and the inmates fled, but Heusdens, refusing to become a Muslim, was bestially killed. Kelet was liberated after a sort of siege. Unfortunately several Javanese Christians in their distress became Muslims, but they later returned to the Christian church. Others, like Sardjo Djojodihardjo and Roebin, held unwaveringly to their Christian faith.

During the Japanese occupation there were many difficulties for the congregations. Europeans were no longer permitted to work with the Javanese. The Japanese took over responsibility for the Germans on the island, and in time transferred the Schmitt and Stauffer families to Tsingtao, China, from where after the war, with the help of the Mennonite Central Committee, they were taken to Reedley, CA. The church union took upon itself all the responsibility for as well as the possession of the former mission properties. The schools could again be opened on condition that the teachers swear an oath of loyalty. This the teachers refused to do, and the schools remained closed. Donorodjo and Kelet were supervised by the Japanese; the German Mennonite head nurse, Maria Klaassen, was allowed to remain. Without the assistance of a physician she managed the hospital with extraordinary skill until 1950. On a return trip to Germany in June 1950 her father Johann Klaassen died at Djakarta. Maria Klaassen later lived in California with the family of Hermann Schmitt. Gramberg tried to continue his work in Djuwana, but he was interned in Kudus. Amstutz worked for a time in secret, but he was then also interned in Kudus with his family. In 1943 the aged missionary Jansz died and in 1944 Hübert's wife died, all of whom had remained in Java. Fast had died in 1941.

The Christian churches worked on under difficult circumstances, especially because the Japanese favored the Muslims. Famine resulted when the Japanese confiscated all the supplies of rice. In August 1945 came fortunately the Japanese surrender and liberation. Meanwhile Indonesian nationalism awakened, and after the revolution and the declaration of independence from Holland all contacts with Europeans became impossible. The Muslims considered themselves the true nationalists; they did not trust the Christians because they belonged to a "western religion." Therefore the Javanese Christians organized a Christian political party, which declared itself in favor of an independent state of Indonesia.

Because of the political confusion in Java and two military missions of the Netherlands, there was for a long time not a single contact with the Dutch Mission Society. To be sure, the Amstutz and Gramberg families returned (1946) to their home countries from the concentration camps. Mrs. Gramberg had died in the internment camp after long suffering. Not until 1949 was it possible to reestablish contact.

Meanwhile a group of workers of the Mennonite Central Committee appeared in Java in 1949, which did much relief work "in the Name of Christ," first in Djakarta, and soon also in Pati and vicinity, with headquarters later in Kelet. Amstutz was sent back to Java as an MCC worker 1949-1950. Beside direct relief the MCC program included a medical clinic, financial aid to the Bible school, and to the local churches. It became clear that the congregations had well survived the emergency. The congregation in the Muria area had endorsed a resolution which had been proposed at a Kwitang conference in Djakarta in 1947. The larger Javanese congregations had all declared themselves independent, and had said that the proclamation of the Gospel in Indonesia was in the first place the task of the national congregations; foreign churches including the Dutch could carry on missions in co-operation with the Indonesian churches; since the national churches were not yet in a position to assume all the responsibilities for the work they had to ask the foreign churches to assist them with workers and with money; but these churches were to understand that the situation in the new state was entirely changed: the missionaries were no longer as formerly to be the leaders of the congregations and of the work, but should rather work in more specialized vocations as needed by the Javanese congregations. In this manner the Muria congregation also asked for help. It had established in Pati a secondary theological school in 1950 to train its preachers. This school was to be the center of spiritual work, for example, for the training of church workers and for the Sunday schools and the spread of Christian literature. For this purpose they asked for three workers. In 1951 Jan F. Matthijssen and his wife went from Holland to Java, Matthijssen becoming a teacher in the theological school and an adviser of the synod. Mrs. Matthijssen organized Sunday-school work. At a synod held at Kelet in December 1951 the foundation was established for medical work, with the hope that it would receive from the Indonesian government the right to administer one or more hospitals. A missionary council was also appointed, with Matthijssen as secretary. In 1952 a second missionary, R. Kuitse, was called by the Pati congregation as a teacher in the theological school. The director of the school is Pastor S. Djojodihardjo. It has now been decided to combine the Pati school with the theological school of the Reformed Church of East Java in Malang in 1955 under a combined board and with Reformed and Mennonite (Kuitse) teachers. For the medical work the Muria church appointed the French Mennonite physician Dr. Marthe Ropp, who with a German Mennonite nurse, Liesel Hege, has already worked in Java for several years under the MCC. Daniel Amstutz was engaged as an itinerant preacher in Europe in the interest of the mission.

The theological school at Pati proved to be a real center for evangelization, for example, through contact with Javanese intellectual circles and library work. An evangelistic periodical, Kabar Baik, was published in the Javanese and Indonesian languages. The Muria church was a member of the ecumenical council of Indonesia.

Since 1951 the Dutch Missionary Society and the Mennonite conferences of France, Germany, and Switzerland have been working together in support of the work in Java in the organization known as the European Mennonite Evangelization Committee (EMEK). In 1953 EMEK spent 30,887.79 guilders for the work in Java. For the work in New Guinea in co-operation with the Dutch Reformed Church the Dutch Mission Association contributed an additional 34,525.06 guilders. The chairmen of the mission association, now called the Doopsgezinde Vereniging tot Evangelie-verbreiding, since the death of Pastor Nijdam (1946) have been Mrs. A. J. Meerdink van den Ban until 1952, W. F. Golterman 1952-1954, and after 1954 Pastor H. Bremer. The secretary in 1955 was C. M. Roggeveen, and the treasurer S. J. Keyzer.

In 1953 the Malay Mennonite Church had 11 congregations, 2,410 members (plus 2,850 children), and 19 ministers, of whom 11 were elders. Following are the statistics by congregations:

| Names | Membership

Baptized Children | |

| Pati | 176 | 122 |

| Margoredjo | 970 | 1144 |

| Kelet | 167 | 262 |

| Bandungardjo | 100 | 91 |

| Margokerto | 132 | 229 |

| Bondo | 103 | 172 |

| Kedung-Pandjalin | 451 | 469 |

| Japara | 27 | 72 |

| Petjanga'an Ngeling | 84 | 100 |

| Kudus | 124 | 132 |

| Kaju-Apu | 76 | 107 |

The Chinese Mennonite Church in Java, which in 1954 had approximately 1,500 members in 9 congregations, arose independently from the Dutch mission program and the Malay church, but as a result of the influence of the mission. It was organized in 1921 and has always been independent. Its center has always been Kudus. Whereas the Malay churches were composed of 95 per cent of small farmers and laborers, relatively poor, the Chinese church was composed more of urban people who are relatively well-to-do.

Both Malay and Chinese churches were represented at the Fifth Mennonite World Conference in August 1952 at Basel, Switzerland, by their respective presidents, S. W. Djojodihardjo for the Malay church, and Tan King Ten for the Chinese church. Both men toured the Mennonite churches in Europe and North America before and after the World Conference. Herman Tan, Jr., and his wife of the Chinese church spent three years in theological study at North American Mennonite institutions in 1952-1955. -- CN, WFG

1987 Update

Politically, economically and culturally Java is the most important island of the island nation of Indonesia. Having 96,892,900 people (in 1987) and 127 million people (in 2005) with a land area the size of England or New York State gives Java a population density of about 864 people per sq. km. The majority of the work force is involved in agriculture.

The Javanese people comprise about 60 percent of the population of Java and inhabit roughly the eastern two-thirds of the island. The Sundanese are the dominant ethnic group on the western third of the island, with a large mixed population from all parts of the archipelago living in the metropolitan area of Jakarta, the nation's capital.

Java's religious, cultural, and political history goes back more than a millennium, with unwritten traditions reaching back much further. Java has been the seat of a series of kingdoms and empires, the most expansive one, Mojopahit, exercising hegemony over a broad sweep of southeast Asia in the 14th century. The aboriginal religion of Java, various forms of Hinduism, Buddhism, Hinduism and Buddhism together, and Islam have been the official religions of successive Javanese kingdoms. Islam became the religion of the majority of the Javanese people under the 350-year rule of The Netherland East India Company and the Dutch Colonial government.

Christianity was introduced among the Javanese little more than 100 years before the end of Dutch colonial rule in 1942. The first Javanese Christian communities took shape in East Java in the second quarter of the 19th century. They were the outgrowth of the work of lay people, e.g., the Indo-European planter Coolen, in the Christian plantation community he established in Ngoro, and the Dutch watchmaker Emde, who worked in Surabaya.

The first Mennonite to be sent overseas as a missionary was sent to the island of Java in 1851. Pieter Jansz was sent out from The Netherlands by the newly formed Dutch Mennonite Missionary Society (the Doopsgezinde Zendingsvereeniging ...) and began to work among the Javanese in the ancient coastal town of Jepara in 1852.

This Mennonite mission work resulted, directly or indirectly, in the formation of the two Mennonite-related conferences on Java. The Gereja Injili di Tanah Jawa (Evangelical Church of Java), has a distinctly Javanese ethnic identity and uses the Javanese language as its primary language of worship. Its city congregations also have Indonesian language services, and most of its conference and organizational activity is conducted in the Indonesian language. The Persatuan Gereja-Gereja Kristen Muria Indonesia (Muria Christian Church of Indonesia), sprang up as an indigenous movement under the leadership of Tee Siem Tat in the midst of the Chinese communities of the towns of the Muria area beginning in the 1920s. The Muria church deliberately branched beyond the Chinese community beginning about 1960 and by 1987 had established mission churches in southern Sumatra, West Kalimantan, and in various areas of Java among several other ethnic groups. -- LMY

See also Indonesia.

Bibliography

Annual reports of the Dutch Mennonite Mission Board, called Jaarsverslag (1848) ff.

Amstutz, Daniel. "Dutch Mennonite Missions During the War." Mennonite Life 3 (January 1948): 16-19.

Amstutz, Daniel. Verslagen van het Doopsgezind zendingsveld op Java over de jaren 1940-1947. Amsterdam: Offsetdruk Erla, [1947?].

Coolsma, Sierk. De zendingseeuw voor Nederlandsch Oost-Indië. Utrecht : Breijer, 1901.

Hein, Gerhard. "Johann Klaassen, Das Lebensbild eines Missionars." Mennonitischer Gemeinde-Kalender (1952): 19-40.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon., 4 v. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe; Schneider, 1913-1967: v. II, 395-97.

Jensma, Th. Doopsgezinde Zending in Indonesia. The Hague: Boekcentrum 1968.

Klaassen, Joh. De Doopsgezinde Zending op Java. Wolvega: Taconis, c1922.

Kuiper, T. Doopsgezinde Bijdragen. (1885): 54-67; (1886): 73-87; (1887): 32-48; (1889): 54-63; (1890): 39-52; (1891): 30-41; (1892): 30-45; (1893): 106-120.

Miller, Robert. "Mennonite Churches in Java." Christian Living 3 (August 1956): 16 ff.

Mulder, A. "A Century of Mennonite Missions." Mennonite Life 3 (January 1948): 12-15.

Nijdam, C. De Doopsgezinde Zending. Wolvega, 1931.

Uit Verleden en heden van de Doopsgezinde Zending 1847-1917 n.p.. n.d)

Yoder, Lawrence M. and Sigit Hem Soekotjo. "Sejarah Gereja Injili di Tanah Jawa" [History of the Evangelical Church of Java]. Unpublished manuscript.

Yoder, Lawrence M. Tunas Kecil: Sejarah Gereja Kristen Muria Indonesia. [Little Shoot: History of the Muria Christian Church of Indonesia]. Semarang: Komisi Literatur Sinode GKMI, no date indicated [1985]. Also available in English translation under the title "The Church of the Muria: A History of the Muria Christian Church of Indonesia." ThM thesis, Fuller Theological Seminary, 1981.

| Author(s) | C., W. F. Golterman Nijdam |

|---|---|

| Lawrence M. Yoder | |

| Date Published | 1987 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Nijdam, C., W. F. Golterman and Lawrence M. Yoder. "Java (Indonesia)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1987. Web. 25 Nov 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Java_(Indonesia)&oldid=88293.

APA style

Nijdam, C., W. F. Golterman and Lawrence M. Yoder. (1987). Java (Indonesia). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 25 November 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Java_(Indonesia)&oldid=88293.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 3, pp. 99-103; v. 5, pp. 465-466. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.