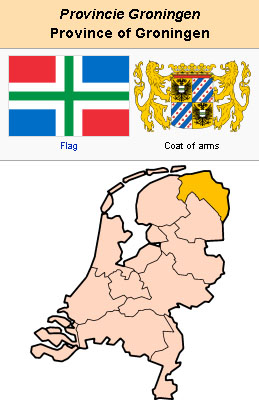

Groningen (Netherlands)

Groningen is a province in the northeastern part of the Netherlands, area 923 sq. mi., (1950 population, 459,819 with 4,375 Mennonites; 2006 population, 574,042). In the Middle Ages this province consisted of a number of different territories: in the north part along the North Sea the districts of Hunsingo and Fivelgo on fertile clay soil, where in early times numerous villages had been built on mounds to protect them from floods; the west part of the province, then called "Westerkwartier," was less fertile; the southeast part (Gorecht and Oldambt districts) was an arid, sandy soil, covered by a thick layer of peat-moor. Shortly after 1400 the city of Groningen became the governing and economical center of all surrounding territories, now forming the province of Groningen, from then on usually called Ommelanden. The north part was often struck by severe floods; this part, now protected from the sea by big dikes, in the mid-20th century was a center of agriculture at a high level (wheat, pulse, potatoes, sugar beets). Shortly after 1600 a start was made to break up the peat-moors in the southeast of the province, a number of canals were made, and after the peat (used for fuel) was dug out, agriculture was possible in this area (potatoes, rye, oats). Here since the 18th century too a growing industrialization developed, especially in the towns of Hoogezand-Sappemeer and Veendam-Wildervank (straw-board factories, distilleries of brandy and gin, iron works).

Besides in the city of Groningen Mennonites in the 16th century were especially found on the fertile grounds of the northern part of the province; they were nearly all farmers (agriculture). The congregations in the former peat-moor district (Sappemeer, Veendam, Pekela, Stadskanaal) are of considerably later date than those on the Hoogeland clay districts.

Concerning the history of the Mennonites, there are large periods with little information. Besides what Blaupot ten Cate gives, there is little material. Hence it is impossible to give a continuous account of its history; the following may, however, be regarded as fairly accurate. As Kühler shows (DB 1917, 1-8), four periods can be distinguished here as in the rest of the Netherlands: (1) from the beginning to about 1581; (2) 1581-1672; (3) 1672-1811 (for Groningen 1826 is more accurate); and (4) the modern period.

From the Beginning to 1581

In the beginning of the 16th century the province of Groningen was very favorably situated. It was a part of the territory of the dukes of Gelderland, who were represented by Stadholders (some of them quite competent). The government was very tolerant; the Reformation (still intra-church) was able to proceed without interruptions. The humanistic clergy (the influence of men. like Wessel Gansfort, was still felt) promoted it rather than the reverse. Gradually and almost unnoticed Anabaptism also arose alongside of the Reformed movement. Its first appearance can no longer be ascertained. In 1533 Viglius van Ayta, provost in Humsterland, wrote to Erasmus that the sect of the Anabaptists had made great progress in Oldehove and Nijehove and all of Groningen. Where did they come from? It is significant that Groningen forms a bridge between Friesland and East Friesland. It is therefore very likely that the influence of Melchior Hoffman was felt here, or at least that of Trijpmaker on his travel through the country en route from Emden to Amsterdam (1530). In 1534 Jacob van Campen and Obbe Philips stayed here for a time. The latter no doubt founded the congregations in Appingedam and 't Zandt and perhaps also the one in the city of Groningen. The presence of Anabaptists in the city is attested by a record of 3 May 1534, which forbids their presence there. On 8 May the Anabaptists were expelled from the province. But these edicts were indifferently enforced; the severest penalties were fines and temporary exile; only one was put to death in Groningen. Up to this time the movement seems to have been chiliastic, but entirely peaceful in character; even when the Münsterites gained the upper hand, the peaceful element was not submerged. "There were peaceful Anabaptists before, during, and after the Münster episode" (Kühler). The revolutionary movement was brief, but very powerful in Groningen. Twenty-eight emissaries were sent out from Münster in 1534. One of them, Claes van Alkmaer, reached the province of Groningen and found two believers ready to return with him to the New Jerusalem. They were Jacob Kremer of Winsum and Tonnis (Antonius) Kistemaecker of Appingedam. In December they returned to spread Rothmann's Van der Wrake, a work of propaganda. Kistemaecker now remained in Appingedam, where there was a considerable Obbenite congregation. He apparently became the originator of the Zandt revolutionary movement, which took place at "de Arcke," the farm of the wealthy Eppe Pieters. About the middle of January 1535 some 1,000 persons assembled here. Hans Schoenmaker proclaimed himself the Messiah; they should kill all priests and government authorities and inherit their kingdom. The local magistrate was powerless to counter the movement. In addition to Schoenmaker, Cornelis in't Kerckhof (Kershof) near Garsthuizen now appeared as "true" Messiah. Now the Stadholder took steps against them; the group itself also turned against Hans. Andries Droogscheerder, with the odd nickname of "Doctor Nenytken," openly expressed his doubt about this Messiah. Hans was imprisoned in Groningen and soon died there, having lost his mind. Cornelis was also seized, but released after giving a confession. The movement can therefore not have been a real threat to the state. Meetings of Anabaptists in Leermens and 't Zandt were dispersed—nothing more happened. In March 1535, when the Frisian revolutionaries stormed the Oldeklooster near Bolsward, the leaders in Groningen also wanted to go there. Seventy men were ready to go, but their wives would not let them go. It was therefore decided to storm the Johannine Commaderie at Warffum. The attack failed. Thirty were arrested; Jacob Kremer, the rabble-rouser, was beheaded at the end of April 1535 at Groningen. The rest were released. The influence of Münster in this coup is evident in the fact that on 25 March 1535, eleven boats were ready on the Ems to sail to Münster. Gradually this influence decreased, and the revolutionary character subsided. Batenburg, who spent the summer of 1535 in Groningen, soon disappeared. His following was slight.

Now the peaceful Anabaptists could come to the fore, especially Dirk Philips and Menno Simons. The former had been ordained as bishop by his brother Obbe in 1536 at Appingedam, but in the next year he moved to Germany (Emden and Danzig). Menno was ordained as bishop by Obbe at Groningen (January 1537) and there baptized a number of persons, including Quirin Pieters, who died as a martyr at Amsterdam in 1545. Menno lived in the province or perhaps in the city "at a quiet place." K. Vos has attempted to show that Menno found a refuge in the home of Christoffer van Ewsum in 1536-1543, who was married to Margareta van Dornum. The "quiet place" was located near Middelstum or Rasquert (near Baflo). (See Krahn, Menno Simons, 35 ft, 57 ff.)

In general, conditions became unfavorable for the Anabaptists when the strictly Catholic emperor Charles V also ruled over Groningen (1536), although he never dared to show himself quite as fanatical in matters of religion as in his hereditary lands. In consequence of a proclamation (1542) threatening him and his followers with death, Menno withdrew from Groningen to East Friesland. Two or three times he was in the province on journeys across it, as in 1549, perhaps in 1551 (1555) and 1557. A prosperous time dawned for the Anabaptists when Leenaert Bouwens began his work. In 1551-1582 he served 22 congregations in the province of Groningen, baptizing about 420 persons, 129 in Appingedam alone.

1581-1672

In the second period came the consolidation of the individual congregations, which took place very quietly. The congregations must soon have become numerous. At the conference at Haarlem in 1589, which was held to consider the affair of Thomas Bintgens, 23 congregations of Groningen were mentioned (East Friesland may have been included). Internally the current divisions also took place here at this time, even though they did not take quite so extreme a form as at some other places. Brixius Gerrits, the elder at Groningen, and Claes Ganglofs, an elder of Emden, played a role in the Bintgens affair (see Huiskoopers). Later Ganglofs took a strict position, with the result that most of the Groningen congregations sided with the Old Flemish. He also had a part in the failure of the union of the Vereenigde Broederschap (1601 united High Germans, Young Frisians, and Waterlanders) with the Flemish, which was promoted by Lubbert Gerrits. At the beginning of the 17th century there were in the province Old Flemish, who were most numerous (united in a conference since about 1635); Flemish, especially in the region bordering on Friesland (likewise united in a conference later on). Among the moderate (with respect to the ban and shunning) Waterlanders were a congregation in Groningen and one in Sappemeer; among the Danziger Old Flemish there was a congregation in Sappemeer and one in Pekela, which fell into a rapid decline about 1787.

A noted personality of this period was Jan Luies (for whom the Jan-Lukasvolk take tlieir name). In the conferences at Hoorn in 1622 (against P. J. Twisck) and at Middelstum in 1628 (against Claes Claesz of Blokzijl), he took a rigorous position among the Flemish in Groningen. In Middelstum he opposed the union of the Frisians and the Flemish (in Harlingen in 1610 and 1626) and rudely rejected the hand of peace extended to the Groningen congregations. In 1632, when most of the Flemish and Old Flemish congregations in Holland united, the churches in Groningen did not join this union.

A strict but pleasant personality, who had great influence in Groningen, was Uko Walles of Noordbroek, a pupil of Jan Luies. Like his teacher he held an unusual view of the benefit of Christ's atoning death for his opponents (see Uko Walles). He was therefore violently persecuted by the government, at the instigation of the intolerant Calvinist clergy. Even those who did not follow Walles suffered under this persecution. Although not all shared his theological views, he had a large following (conference in Groningen 23 February-7 March 1637). The relationship of his group with the Old Flemish is not entirely clear. In the rural congregations they are probably to be counted identical (all known as Groninger Old Flemish). In the city of Groningen they were for a time distinct, but by 1677 they were again united.

The Ukowallists maintained the strict views of Menno and Dirk Philips on the Incarnation. They baptized all that came to them, even though they had previously been baptized in a congregation in another branch. Baptism was usually by immersion. They exercised the ban in its severest form especially in cases of marriage with persons outside the congregation. Old customs that threatened to disappear (such as feetwashing) they conscientiously maintained. Also outside of Groningen Uko Walles had a following. The number of Ukowallists in Friesland is estimated at 600.

What was the attitude of the outside world to the Mennonites? In 1568 the War of Liberation against Spain began. Groningen was also severely oppressed by the Spaniards, whose troops were continuously marching through the province. In 1583 the Mennonites were again severely persecuted. In the country they were compelled to attend the Catholic Church and have their children baptized. In the same year Brixius Gerrits was expelled from the city. In 1594 the Catholics were expelled; the established church was now the Reformed. In 1601 an edict was passed that made the position of the Mennonites even more difficult although the magistrates did not execute it very rigorously. But it is clear that the Mennonites were not very favorably accepted, as the writings of the Groningen chronicler Ubbo Emmius (see his Rerum Frisicarum, historia 1616) show. In 1637-1661 the government repeatedly opposed Uko Walles, banishing him and creating many difficulties for all the Mennonites, not only for his followers. The congregation at Wildervank-Veendam, which came into being at this time, was thereby seriously hampered. In 1662 an edict permitted the Mennonites to hold their services "as of old." They were given complete toleration in 1672. In this year of distress when the army of the Bishop of Münster made raids upon this province, the Mennonites most convincingly proved their loyalty to the state, and henceforth they were left in peace.

1672-1826

The third period (1672-1826), especially in its latter part, is a period of decline. The differences between the old parties in the Netherlands were less sharp. But they were not entirely eliminated, for instance, in North Holland, where in place of the older divisions, the Zonists and Lamists were the opposing parties. In the 18th century there was in Groningen a clearly perceptible difference between the Old Flemish and the Flemish. The latter followed the Lamists. The Old Flemish Societeit was so strongly Zonist that it seriously considered uniting with die Zonist Sociëteit (the negotiations in 1766 proved abortive). But even the conservatives did not escape the spirit of the time, which favored softening of lines. Thus the ban was applied less and less, was omitted, or rather leniently enforced, usually only for a short period. Gradually marriage with persons outside the congregation was at least tolerated, if not exactly permitted. In 1743 the Old Flemish decided that members of other creeds who had married into the Mennonite Church should for a certain period be denied spiritual communion. Silent prayer was replaced by audible prayer. In 1749 it was left to the discretion of each individual preacher to decide this question. The authority of the elders decreased. Since 1749 baptism and communion have been in the hands of the congregation. Organs (previously shunned as a sign of worldliness) were introduced in Groningen in 1785, and in Sappemeer in 1808. In 1898 only seven of the 15 congregations had organs; now there is one in every church. Feetwashing— maintained longest by the Old Flemish—was dropped during the second half of the 18th century. Indeed, even the magistrate's office was no longer repudiated. Nonresistance was in danger of being lost, when many volunteers ranked themselves with the "Patriots." Nonresistance as a principle had, strictly speaking, been sacrificed in 1672, when the Mennonites participated at least indirectly in the war. With respect to their standards of moral conduct, they remained true to the faith of their fathers. Their virtues were acknowledged even by their worst enemies. Their dependability and reliability in business and honesty in dealing were proverbial.

Nevertheless the congregations declined rapidly in numbers. The Mennonites of this province— except those living in the city of Groningen—were almost exclusively farmers, engaged in agriculture or cattle raising. Conditions of agriculture were very bad in the early 18th century and many farmers became pauperized or moved away. Besides this, recurring floods caused tremendous losses to the congregations. A severe flood broke the dikes of the sea at a number of places on 11 November 1686; 80 Mennonites, including 55 children, were drowned, while more than 1,400 head of cattle owned by Mennonite farmers perished. The worst flood was that of 1717. In this year on Christmas day large areas were flooded; 9 brethren, 26 sisters, and 37 children perished; material losses were considerable; houses and barns were destroyed, and Mennonite farmers lost 909 cows, 192 horses, 703 sheep, and 68 pigs.

This meant severe loss for the churches. But there were other reasons why the congregations decreased. Their preachers were unable to compete with the trained ministers of the Reformed Church. Many members transferred their membership to the Reformed Church. The congregations of Bierum, Baflo, and Usquert disappeared altogether. Appingedam was dissolved about 1780; one part settled in adjacent Leermens (about 1700). Ulrum became extinct in 1794; it probably still had a considerable number of members, many of whom joined the Reformed Church. Other congregations, no longer able to maintain their independence, united. Thus the Pieterzijl congregation came into being about 1685, and the union of the Flemish and Old Flemish congregations in Humsterland (since 1838 called Noordhorn) occurred in 1775; Huizinge (now Middelstum), Sappemeer, where the six or more congregations gradually merged with the Old Flemish, Groningen, and finally Mensingeweer (1818) originated from several unifications. To be sure, there was an influx of Mennonites from the Palatinate and Switzerland. Some of the Palatine Mennonites, expelled from their homes in 1694, and the Swiss Mennonites, expelled from their country in 1710-1713, for the most part fled to the Netherlands, and settled principally in Groningen, in the city as well as in the vicinity and in Sappemeer. Money was collected throughout the country to buy farms for them, especially in Hoogkerk and Adorp. These foreigners, who were at first organized into congregations of their own, merged with the Dutch congregations in the first half of the 19th century. There are now among the Dutch Mennonites many descendants of the Swiss refugees, such as the Boer, Leutscher, and Meihuizen families.

Although the progressive Lamists and Socinians were never numerous in this province, there were from early times deviating opinions. This is indicated by the 12 questions (Geuzenfragen) drawn up by the state to counter forbidden opinions (used without success in 1660-1670). That such opinions also crept into the Mennonite Church is clear in the fact that there was a Collegiant congregation (in the late 17th and early 18th centuries), which, to be sure, had connections with the United Flemish and Waterlanders in Groningen (see Botterman). A government resolution of 6 December 1701 calls the Collegiants (erroneously, of course) a new sect of Mennonites. Since the resolutions referred only to the city, the rural area was apparently free of Collegiantism.

At the end of the 18th century the situation was deplorable. Some congregations had disintegrated, many were on the verge of doing so; their churches were dilapidated, their members impoverished, their numbers small; while on the other hand the number of unbaptized persons was uncommonly large. The credit for their ability to survive and even to achieve a revival is due in the first place to the endurance of the people of Groningen, but also to two other factors, viz., the acceptance of preachers trained by the Mennonite Seminary—one of the first in Groningen province was Gerrit Bakker in the Noordhorn congregation (1818-1871)— and the establishment of the Groningen Sociëteit (1826).

1826-Modern Period

Most of the congregations made a more rapid growth in 1815-1850. Thereafter the membership again suffered a gradual decline. The 13 congregations existing at the time of the founding of the Sociëteit (Groningen, Den Horn, Noordhorn, Middelstum, Leermens-Loppersum, Midwolda now Winschoten, Sappemeer, Mensingeweer, Noordbroek-Nieuw Scheemda, Pieterzijl or Grijpskerk, Zijldijk, Uithuizen, and Veendam-Pekela) are all still in existence, though some are very small. New congregations that have been added are Stadskanaal, which branched off from Veendam in 1850 and had a minister of its own (from 1917 to 1950 in combination with Assen), and Pekela, which became an independent congregation in 1852, but has always been combined with Veendam. More recently new congregations were founded in Haren and Roden.

Almost imperceptibly Modernism overtook the Groningen congregations in the 1870s and later. Only in the city of Groningen was there some difficulty. In the rural congregations many who remained orthodox and did not follow the pastors and the majority of the congregations united with the Doleerenden (members of the Reformed Church who had left the main body in 1886) or the Baptists. In the mid-20th century the Groningen congregations were without exception liberal.

There were capable men in the province of Groningen in the 19th century. One of the outstanding men was Simon Gorter, minister of Zijldijk 1813-1856, who saved and brought to new life not only his own congregation, but also the congregations of Uithuizen and Leermens-Loppersum. A. Winkler Prins, the minister of Veendam 1850-1882, a versatile scholar, and editor of a general encyclopedia, was another leader.

The first half of the 20th century was for many congregations a period of disintegration. Nearly half of them were without a pastor. In the 1950s nearly all the congregations had a pastor, but a number of congregations have merged.

Whereas the population of Groningen is increasing, the number of Mennonites has been declining. The total number of baptized members in this province in 1953 was 2,601; in 1834 it was 4,050. The percentages are as follows: 1733, 4.5 per cent of the population were Mennonite; 1775, 2.3 per cent; 1834, 1.6 per cent; 1900, 0.8 per cent; 1947, 0.6 per cent. This decrease is partly caused by the fact that many Mennonites moved from this province to other parts of the Netherlands.

The following congregations are found in the province of Groningen,

with the following memberships:

| Congregation | 1834 | 1900 | 1955 |

| Groningen | 230 | 1017 | 1021 |

| Grijpskerk | 42 | 87 | 48 |

| Den Horn | 95 | 67 | 44 |

| Leermens-Loppersum | 42 | 98 | 90 |

| Mensingeweer | 44 | 100 | 75 |

| Middelstum | 61 | 74 | 34 |

| Noordbroek | 85 | 82 | 28 |

| Noordhorn | 56 | 89 | 75 |

| Pekela | -- | 40 | 45 |

| Sappemeer | 255 | 494 | 270 |

| Stadskanaal | -- | 106 | 85 |

| Uithuizen | 30 | 98 | 98 |

| Veendam | 140 | 240 | 127 |

| Zijldijk | 61 | 83 | 69 |

| Grootsgast (Kring) | -- | -- | 13 |

| Haren (Kring) | -- | -- | 111 |

| Oldehove (Kring) | -- | -- | 10 |

| Total | 1141 | 2675 | 2243 |

Bibliography

Bos, P. G. "De Groningen Wederdooperswoelingen in 1534 en 1535." Nederlands Archief voor Kerkgeschiedenis, n.s., 6 (1906): 1-17.

Brucherus, Heino Hermannes. Geschiedenis van de opkomst der Kerkhervorming in de Provincie Groningen, tot aan het jaar 1594. Groningen: Oomkens, 1821.

Cate, Steven Blaupot ten. Geschiedenis der Doopsgezinden in Groningen, Overijssel en Oost-Friesland, 2 vols. Leeuwarden: W. Eekhoff en J. B. Wolters, 1842.

Cate, Steven Blaupot ten. Geschiedenis der Doopsgezinden in Friesland. Leeuwarden: W. Eekhoff, 1839.

Dassel, H., Sr. Menno's volk in Groningen: geschiedenis der Doopsgezinde Gemeenten binnen de stad Groningen. Groningen: Schut, 1952.

Doopsgezinde Bijdragen (1872): 2; (1879): 1-10; (1917): 105.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. II, 178-83.

Hofstede de Groot, C. P. Geschiedenis der Broederenkerk te Groningen: eene bijdrage tot de geschiedenis der Hervorming en der roomschgezinde gemeente in deze stad. Groningen: Oomkens, 1832.

Hoop Scheffer, Jacob Gijsbert de. Inventaris der Archiefstukken berustende bij de Vereenigde Doopsgezinde Gemeente to Amsterdam, 2 vols. Amsterdam: Uitgegeven en ten geschenke aangeboden door den Kerkeraad dier Gemeente, 1883-1884: I, Nos. 136, 164, 201, 223, 265, 374, 470, 473, 557, 558, I, II, V, 562-565, 571, 575-577, 579, 590, 594, 597, 600, 605 f., 1069, 1087-1091, 1093, 1096-1098, 1111-1114, 1189, 1608, 1610, 1627, 1636, 1638, 1645, 1664, 1730, 1732-1736, 1866 f., 1873-1880, 1886-1902.

Krahn, Cornelius. Menno Simons (1494-1561): ein Beitrag zur Geschichte und Theologie der Taufgesinnten. Karlsruhe, 1936.

De kroniek van Abel Eppens tho Equart. Amsterdam: Müller, 1911.

Pathuis, A. Inventaris van het Oud-Archief den Ver. Doopsgez. Gemeente te Groningen. Groningen, 1940.

Vox, Karel. Articles in various issues of the Groningsche Volksalmanak.

Vos, Karel. Het Honderdjarig bestaan der Societeit van Doopsgezinde Gemeenten in Groningen en Oost-Friesland. Groningen, 1926.

Wumkes, G. A. De Gereformeerde kerk in de Ommelanden tusschen Eems en Lauwers, (1595-1796). Groningen: Noordhoff, 1904: 30-34.

| Author(s) | Nanne van der Zijpp |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1956 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Zijpp, Nanne van der. "Groningen (Netherlands)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1956. Web. 1 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Groningen_(Netherlands)&oldid=170079.

APA style

Zijpp, Nanne van der. (1956). Groningen (Netherlands). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 1 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Groningen_(Netherlands)&oldid=170079.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, pp. 589-592. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.