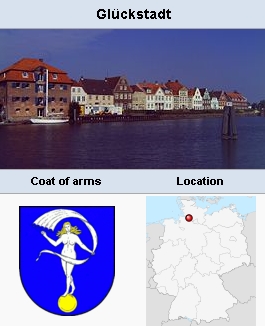

Glückstadt (Schleswig-Holstein, Germany)

Glückstadt, a town on the right bank of the lower Elbe (coordinates: 53° 47′ 30″ N, 9° 25′ 19″ E) near Hamburg (now Germany), was founded in 1616 by Christian IV of Denmark to compete with ambitious and thriving Hamburg, which then no longer belonged to his realm. To attract desirable settlers he gave the city a charter of religious freedom.

The citizenry were divided into three nationalities, which brought about some friction; there were Germans (Lutherans and Catholics), Dutch (Remonstrants, Reformed, and Mennonites), and Portuguese (Jews). Glückstadt was then, besides Friedrichstadt a.d. Eider, Altona, and Rendsburg, the only place in North Germany and Denmark with religious liberty, with the exception of several German settlements in Polish territory, like Danzig.

The Dutch and Portuguese enjoyed complete civil and religious liberty, as well as freedom from all military obligations; they had their own judges in civil and commercial matters, and their own arrangements for weddings, baptism, burial, and costume. They could carry on commerce and trade, and exercise any vocation without joining the guilds, which was generally compulsory at that time; and what was most important, they could practice thieir religious convictions without hindrance.

Very little is known about the Mennonites in Glückstadt, for there are no church records. It is thus not known when the first Mennonites moved into the city; but it is recorded that in March 1623 citizens were accepted without requiring an oath of them. These must have been Mennonites. In the new charter of 1631 the "Mennonists" are specifically mentioned; "They shall live their religion and conscience freely, and not be burdened with any oath, use of arms, or the baptism of their children." For release from military service they had to pay "a suitable annual fee," the amount of which is not known; and at the same time the Mennonites, Calvinists, and Remonstrants together received two acres of land outside the city for burial sites for 50 talers. (The former Mennonite cemetery is now a Catholic cemetery, with no reminders of former times.) The Calvinists and Remonstrants had a church, preacher, and a school in common. There probably never was a Mennonite school; according to a regulation of 1692 they were to send their children to the (Lutheran) city school. The Mennonites of course also bore their share of the common civic expenses, such as in building the city hall in 1642-1643. They had to request the renewal of their charter "every 10 or 20 years until 1700.

The Mennonites of Glückstadt were considered part of the Friedrichstadt congregation, as is shown in the archives of the Friedrichstadt congregation. Gert Henriks, the elder at "Frederikstad," was repeatedly in Glückstadt in 1633-1639, to receive new members by baptism. In this connection names like the following are recorded: Albrantz, Ariens, Clasen, Cornils, Hardelop, Jacobs, Jansen, Müllienz, Peters, Siletz; and Christian names like Clas, Dirk, Gerrit, Jan, Jakob, Altje, Gritje, Maartje, Trien—all of them Dutch Frisian names. Discipline was apparently strict; for example, in 1633 a member was excommunicated for misconduct, and in 1645 a woman was expelled for marrying a non-Mennonite. On 12 May 1639 a resolution was passed at a conference in Hamburg to separate Glückstadt from Friedrichstadt; from now on it was a part of the Hamburg (Altona) congregation, which was much nearer to them, and where Mennonitism could now develop much more freely than formerly. But Glückstadt had its own minister at least at times. In 1641 the Mennonites requested for their preacher freedom from the burden of quartering troops, and refer to a former royal mandate granting this freedom to "one who serves religion." Through visiting preachers connections were maintained with the homeland for a long time; for example, in 1663 Bastiaan van Weenigem, the minister of the Rotterdam congregation, stayed there for a short time when he visited several Low German churches.

The contribution of the Mennonites to the city's progress was probably not slight. In 1635 a Jakob Berentz of Hamburg settled here, whose "people and workers belonged to the Mennonite religion." He was probably a factory owner or a shipper and himself a Mennonite. In 1643 Gysbert van der Smissen II (b. 1620 in Haarlem in Holland, and had been a journeyman baker in Friedrichstadt) moved from Friedrichstadt to Glückstadt with his mother, the widow of Daniel Gysbert van der Smissen. He is said to have organized the guild of cake bakers there. But his chief importance to the city lay in his commercial activities. His ships went to Norway and France; in favorable seasons they penetrated to Greenland to catch seals and whales, an industry which he founded with other wealthy citizens. In the middle of the 17th century Glückstadt was probably at the peak of its importance as the trade, center of the lower Elbe, largely through the activities of the van der Smissens. But soon thereafter a rapid decline set in, in consequence of the disturbances of war involving the city (Spanish trade was, for example, constantly disturbed by the outriggers of Dunkirk), for in spite of the urgent advice of die colonists to the contrary, the Danish king had made a fortress of the city.

Gysbert van der Smissen II and probably many others immigrated to Altona, where the family continued to prosper, especially in his son Hinrich, called "founder of cities" because of his activities in construction and building in Altona. In 1678 Gysebrecht Daniel van der Schmissen (probably Gysbert Daniel) sold his farm at the Kremper Tor. The desire of the colonists to emigrate was strengthened by repeated disregard for their charter, which declared them free for all time from military burdens in the time of war; they sent several complaints and appeals to the king. (In petitions for release from these obligations, they pointed to the beautiful "liberty" in Hamburg and Altona, as a threat of emigration.) These conditions also led to differences between the "privileged" persons and the city government (president, mayor, and council), who belonged to the "unprivileged" German population. To look after their interests the several nationalities or confessions had appointed deputies; it is not known when this was begun. The deputy appointed by the Mennonites in 1685 was Daniel van der Smissen. He also represented the brotherhood in the conflict with the guild of silk and cloth dealers, who were naturally interested in limiting the free trade of nonmembers. The relations of the Mennonites with other religious groups were probably, on the whole, good; only one exception is known. In the winter of 1684-1685 the relations were disturbed by a dispute with the Reformed about the cemetery keys, for the income from the cemetery was connected with the possession of the keys. The keys had hitherto been in die possession of the deputies of the nation, who were for a long time two members of the Reformed Church. When, after the death of one of these deputies, Daniel van der Smissen was appointed co-deputy, the Reformed claimed that the keys belonged to them. The president and council sided with the Reformed, but the chancellery, to whom van der Smissen and Lambert Gerts as leader of the Mennonites appealed, decided essentially in favor of the Mennonites. (After the Mennonites died out the cemetery was left in the hands of the Reformed.)

The Mennonites in Glückstadt also took the usual Mennonite position of tolerance toward other faiths. In 1660-1661, when many English dissenters fled the Anglican reaction of Charles II and sought protection on the shores of the North Sea, Frederick III issued mandates for his entire realm, forbidding the reception of "banished Quakers or fanatics." The Mennonites were especially mentioned, and were threatened with loss of their privileges if they disregarded the mandates.

Emigration and the dying out of families reduced the number of Mennonites more and more. About 1740 the last one died. The chapel passed into the possession of the Altona congregation; it was remodeled into a dwelling and rented out. In 1792, when royal permission was granted to sell the house, it was already quite dilapidated. Although the charter remained in force in Glückstadt, there were no more Mennonites there afterward.

Bibliography

Cate, Steven Blaupot ten. Geschiedenis der Doopsgezinden in Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht en Gelderland, 2 vols. Amsterdam: P.N. van Kampen, 1847: I.

Detlefsen, Detlef. "Die städtische Entwicklung Glückstadts unter König Christian IV." Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Schleswig-Holsteinische Geschichte 36: 196 ff.

Dollinger, Robert. Geschichte der Mennoniten in Schleswig-Holstein, Hamburg und Lübeck. Neumünster: Wachholtz, 1930.

Doopsgezinde Bijdragen (1891): 94.

Familienchronik der Familie van der Smissen. Danzig, 1875.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. II, 124-126.

Mennonitische Blätter (1858): 35 ff.

Roosen, Berend Carl. Geschichte der Mennoniten-Gemeinde zu Hamburg und Altona. Hamburg: [B.C. Roosen], 1886-1887: I-II

Maps

Map:Glückstadt (Schleswig-Holstein, Germany)

| Author(s) | Robert Dollinger |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1956 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Dollinger, Robert. "Glückstadt (Schleswig-Holstein, Germany)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1956. Web. 24 Nov 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Gl%C3%BCckstadt_(Schleswig-Holstein,_Germany)&oldid=125037.

APA style

Dollinger, Robert. (1956). Glückstadt (Schleswig-Holstein, Germany). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 24 November 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Gl%C3%BCckstadt_(Schleswig-Holstein,_Germany)&oldid=125037.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, pp. 526-528. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.