Difference between revisions of "Arnold, Gottfried (1666-1714)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m (Text replace - "<em>, </em>" to ", ") |

m (Text replace - "<strong> </strong>" to " ") |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

In 1696 Arnold published his first major work, <em>Die erste Liebe, das ist die wahre Abbildung der ersten Christen nach ihrem lebendigen Glauben und Leben, </em>an almost revolutionary book of the new trend that established his fame and brought him an appointment as professor at the University of Giessen in 1697, which he resigned a year later. This book gives a new picture of the primitive church as the ideal brotherhood to be emulated. Its appeal was tremendous throughout the 18th century (six editions appeared up to 1780, latest European edition 1845) and continued also its value as a favorite devotional reader among the Pennsylvania Germans (numerous editions in America). | In 1696 Arnold published his first major work, <em>Die erste Liebe, das ist die wahre Abbildung der ersten Christen nach ihrem lebendigen Glauben und Leben, </em>an almost revolutionary book of the new trend that established his fame and brought him an appointment as professor at the University of Giessen in 1697, which he resigned a year later. This book gives a new picture of the primitive church as the ideal brotherhood to be emulated. Its appeal was tremendous throughout the 18th century (six editions appeared up to 1780, latest European edition 1845) and continued also its value as a favorite devotional reader among the Pennsylvania Germans (numerous editions in America). | ||

| − | Three years later, Arnold published his | + | Three years later, Arnold published his <em>opus magnum, </em>the <em>Unpartheiische Kirchen- und Ketzer-Historie (</em>first edition at Frankfurt a. M., 1699-1700, second edition 1729, an enlarged third edition, edited by others, at [[Schaffhausen (Switzerland)|Schaffhausen]] 1740-1742 in three large folio volumes). In a sense it was an epoch-making work, being strictly in opposition to official Lutheran church historiography. Following the footsteps of [[Franck, Sebastian (1499-1543)|Sebastian Franck]] he arrived at a new and original appreciation of the free church movements that the established churches called "heretical" and stigmatized as "sects." To Arnold, just the opposite was true: "Those who make heretics are the heretics proper, and those who are called heretics are the real God-fearing people" <em>("Die Ketzermacher sind die eigentlichen Ketzer, und die Verketzerten sind die wahrhaft Frommen"). </em>In search for true representatives of an inward Christianity, Arnold found many original sources both of medieval sectarian movements and of [[Anabaptism|Anabaptism]] of the 16th century. For the latter he could use the recently published [[Annales Anabaptistici (Monograph)|<em>Annales Anabaptistici </em>]]by [[Ottius, Johann Heinrich (ca. 1617-1682)|J. H. Ottius]] (Basel, 1672), the <em>[[Geistliches Blumengärtlein|Geistliches Blumengärtlein]] </em>(Amsterdam, 1680), and similar volumes. His detailed presentation and appreciation of the Anabaptists and Mennonites fills no less than 250 pages of the 1740 edition (namely, I, 856-899, 1299-1310, 1313-1500; II, 159-167, 1059-1065). A large section was devoted also to reprints of the writings of [[David Joris (ca. 1501-1556)|David Joris]]<em>.</em> |

| − | Arnold manifests a fine knowledge and grasp of Anabaptism (including the [[Hutterian Brethren (Hutterische Brüder)|Hutterites]]) and Mennonitism, and his work did much to dispel false prejudices among the general public. In this sense Arnold's <em>Ketzer-Historie </em>might well be considered as a real continuation of Sebastian Franck's similar work, the [[Chronica, Zeytbuch vnd geschychtbibel|<em>Chronica </em>]]of 1531. In the 18th century this type of church historiography greatly expanded and helped to rehabilitate those despised groups (see [[Ketzer-Historie and Ketzer-Lexikon|Ketzer-Historie]]). The influence | + | Arnold manifests a fine knowledge and grasp of Anabaptism (including the [[Hutterian Brethren (Hutterische Brüder)|Hutterites]]) and Mennonitism, and his work did much to dispel false prejudices among the general public. In this sense Arnold's <em>Ketzer-Historie </em>might well be considered as a real continuation of Sebastian Franck's similar work, the [[Chronica, Zeytbuch vnd geschychtbibel|<em>Chronica </em>]]of 1531. In the 18th century this type of church historiography greatly expanded and helped to rehabilitate those despised groups (see [[Ketzer-Historie and Ketzer-Lexikon|Ketzer-Historie]]). The influence of Arnold's work upon official church historians toward a more impartial evaluation of independent groups cannot be doubted, though at first the book occasioned a vigorous controversy with orthodox Lutherans, for new editions of the work appeared long after his death, in 1729 and 1740-1742. |

All told, Arnold wrote about 50 books, mostly of a mystical-devotional character, some of which also found much response among German Mennonites. In 1700 he published <em>Das Geheimnis der göttlichen Sophia, </em>a book clearly following the line of the Christian theosophy of Jakob Boehme (died 1624). In 1704, another popular book was published, <em>Wahre Abbildung des inwendigen Christentums </em>(3rd edition, 1733), which found its way into many Mennonite homes of both continents. One of his latest books, <em>Theologia Experimentalis, oder Geistliche Erfahrungslehre, Erkenntnis und Erfahrung in den vornehmsten Stücken des lebendigen Christentums, </em>of 1714, was reprinted in Pennsylvania in 1855 by [[Oberholtzer, John H. (1809-1895)|John Oberholtzer]], the leader of the later [[General Conference Mennonite Church (GCM)|General Conference Mennonite]] group, and advertised in the latter's <em>Der Religiöse Beobachter </em>as a highly recommended devotional book. It represents again this type of semi-mystical and subjective inward Christianity, not bound to any ecclesiastical body but also not pressing toward radical commitments and witnessing in the world. It is a book of the <em>Stillen im Lande</em> | All told, Arnold wrote about 50 books, mostly of a mystical-devotional character, some of which also found much response among German Mennonites. In 1700 he published <em>Das Geheimnis der göttlichen Sophia, </em>a book clearly following the line of the Christian theosophy of Jakob Boehme (died 1624). In 1704, another popular book was published, <em>Wahre Abbildung des inwendigen Christentums </em>(3rd edition, 1733), which found its way into many Mennonite homes of both continents. One of his latest books, <em>Theologia Experimentalis, oder Geistliche Erfahrungslehre, Erkenntnis und Erfahrung in den vornehmsten Stücken des lebendigen Christentums, </em>of 1714, was reprinted in Pennsylvania in 1855 by [[Oberholtzer, John H. (1809-1895)|John Oberholtzer]], the leader of the later [[General Conference Mennonite Church (GCM)|General Conference Mennonite]] group, and advertised in the latter's <em>Der Religiöse Beobachter </em>as a highly recommended devotional book. It represents again this type of semi-mystical and subjective inward Christianity, not bound to any ecclesiastical body but also not pressing toward radical commitments and witnessing in the world. It is a book of the <em>Stillen im Lande</em> | ||

Revision as of 03:09, 13 April 2014

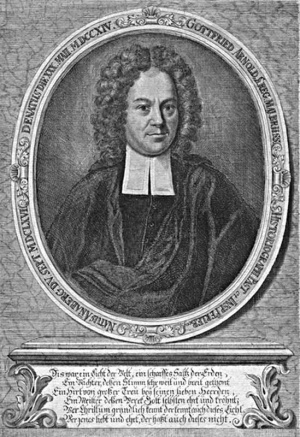

Gottfried Arnold was a German Pietist, church historian, independent author of devotional books, and from 1704 to his death pastor of a Lutheran church in Brandenburg. As the most prominent mediator between Anabaptism and German Pietism he was widely read among the Mennonites of the 18th and 19th centuries, and exerted a tangible influence upon the Mennonite church as a whole toward a more pietistic and "inward" Christianity. In studying Arnold, one must distinguish between the earlier independent author (1696-1704) who opposed the doctrinal and ecclesiastical orthodoxy of his time, and the later church man who found some reconciliation with the established Lutheran theology (1704-1714). The influence of J. P. Spener (died 1705) and rising Pietism is quite obvious in his writings, yet Arnold pursues his own ways and is in a strict sense not a follower of Spener. He might be better characterized as a pietistic separatist who distrusted dogma and ecclesiasticism altogether, and who sought a semi-mystical foundation of his faith in the subjectivity of religious experience, following somewhat the lead of Johann Arndt (died 1621) and Valentin Weigel (died 1588).

In 1696 Arnold published his first major work, Die erste Liebe, das ist die wahre Abbildung der ersten Christen nach ihrem lebendigen Glauben und Leben, an almost revolutionary book of the new trend that established his fame and brought him an appointment as professor at the University of Giessen in 1697, which he resigned a year later. This book gives a new picture of the primitive church as the ideal brotherhood to be emulated. Its appeal was tremendous throughout the 18th century (six editions appeared up to 1780, latest European edition 1845) and continued also its value as a favorite devotional reader among the Pennsylvania Germans (numerous editions in America).

Three years later, Arnold published his opus magnum, the Unpartheiische Kirchen- und Ketzer-Historie (first edition at Frankfurt a. M., 1699-1700, second edition 1729, an enlarged third edition, edited by others, at Schaffhausen 1740-1742 in three large folio volumes). In a sense it was an epoch-making work, being strictly in opposition to official Lutheran church historiography. Following the footsteps of Sebastian Franck he arrived at a new and original appreciation of the free church movements that the established churches called "heretical" and stigmatized as "sects." To Arnold, just the opposite was true: "Those who make heretics are the heretics proper, and those who are called heretics are the real God-fearing people" ("Die Ketzermacher sind die eigentlichen Ketzer, und die Verketzerten sind die wahrhaft Frommen"). In search for true representatives of an inward Christianity, Arnold found many original sources both of medieval sectarian movements and of Anabaptism of the 16th century. For the latter he could use the recently published Annales Anabaptistici by J. H. Ottius (Basel, 1672), the Geistliches Blumengärtlein (Amsterdam, 1680), and similar volumes. His detailed presentation and appreciation of the Anabaptists and Mennonites fills no less than 250 pages of the 1740 edition (namely, I, 856-899, 1299-1310, 1313-1500; II, 159-167, 1059-1065). A large section was devoted also to reprints of the writings of David Joris.

Arnold manifests a fine knowledge and grasp of Anabaptism (including the Hutterites) and Mennonitism, and his work did much to dispel false prejudices among the general public. In this sense Arnold's Ketzer-Historie might well be considered as a real continuation of Sebastian Franck's similar work, the Chronica of 1531. In the 18th century this type of church historiography greatly expanded and helped to rehabilitate those despised groups (see Ketzer-Historie). The influence of Arnold's work upon official church historians toward a more impartial evaluation of independent groups cannot be doubted, though at first the book occasioned a vigorous controversy with orthodox Lutherans, for new editions of the work appeared long after his death, in 1729 and 1740-1742.

All told, Arnold wrote about 50 books, mostly of a mystical-devotional character, some of which also found much response among German Mennonites. In 1700 he published Das Geheimnis der göttlichen Sophia, a book clearly following the line of the Christian theosophy of Jakob Boehme (died 1624). In 1704, another popular book was published, Wahre Abbildung des inwendigen Christentums (3rd edition, 1733), which found its way into many Mennonite homes of both continents. One of his latest books, Theologia Experimentalis, oder Geistliche Erfahrungslehre, Erkenntnis und Erfahrung in den vornehmsten Stücken des lebendigen Christentums, of 1714, was reprinted in Pennsylvania in 1855 by John Oberholtzer, the leader of the later General Conference Mennonite group, and advertised in the latter's Der Religiöse Beobachter as a highly recommended devotional book. It represents again this type of semi-mystical and subjective inward Christianity, not bound to any ecclesiastical body but also not pressing toward radical commitments and witnessing in the world. It is a book of the Stillen im Lande

Arnold was also a successful hymn writer. Some of his hymns such as "So führst Du doch recht selig," "O Durchbrecher aller Banden," "Frag deinen Gott," and several more have found a place in the hymnals of the German Mennonites.

Bibliography

Friedmann, Robert Mennonite Piety Through the Centuries: its Genius and its Literature. Goshen, Ind.: Mennonite Historical Society, 1949.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. I, 85.

Seeberg, Erich. Gottfried Arnold, die Wissenschaft und Mystik seiner Zeit, Studien zur Historiography und Mystik. Leipzig, 1923.

Seeberg, Erich. Gottfried Arnold in Auswahl herausgegeben. München, 1934. (This collection omits all passages concerning Anabaptists and Mennonites).

| Author(s) | Robert Friedmann |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1953 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Friedmann, Robert. "Arnold, Gottfried (1666-1714)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1953. Web. 25 Nov 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Arnold,_Gottfried_(1666-1714)&oldid=120056.

APA style

Friedmann, Robert. (1953). Arnold, Gottfried (1666-1714). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 25 November 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Arnold,_Gottfried_(1666-1714)&oldid=120056.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, pp. 164-165. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.