Difference between revisions of "Makhno, Nestor (1888-1934)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

AlfRedekopp (talk | contribs) |

AlfRedekopp (talk | contribs) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

Smith, C. Henry. <em>The Story of the Mennonites. </em>Newton, KS, 1950. | Smith, C. Henry. <em>The Story of the Mennonites. </em>Newton, KS, 1950. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sysyn, Frank. "Nestor Makhno and the Ukrainian Revolution" in ''The Ukraine: 1917-1921, a study in revolution.'' Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1977: 271-304. | ||

Toews, Heinrich. <em>Eichenfeld-Dubowka: ein Tatsachenbericht aus der Tragödie des Deutschtums in der Ukraine. </em>Karlsruhe I.B. :H. Schneider, [1938]. | Toews, Heinrich. <em>Eichenfeld-Dubowka: ein Tatsachenbericht aus der Tragödie des Deutschtums in der Ukraine. </em>Karlsruhe I.B. :H. Schneider, [1938]. | ||

| − | {{GAMEO_footer|hp=Vol. 3, pp. 430-431|date=1957|a1_last=Rempel|a1_first=John G|a2_last= |a2_first= }} | + | {{GAMEO_footer|hp=Vol. 3, pp. 430-431|date=1957; 2024|a1_last=Rempel|a1_first=John G|a2_last= |a2_first= }} |

Latest revision as of 12:03, 18 June 2024

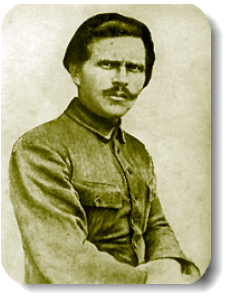

Nestor Makhno (26 October 1888 - 25 July 1934), commander of an army of anarchists in South Russia during the Revolution of 1918-1921, at a time when various Russian armies of divers political inclinations were contending for the possession of the Ukraine. Since this movement rejected every form of government (on their flags, was the inscription: anarchy is the mother of all order), their hostility was directed not only toward the rightist parties, but also against the communists, who were not sufficiently radical. This army that at one time is supposed to have numbered 100,000 men was recruited chiefly from the ranks of the poor Ukrainian peasantry. Every estate holder, industrialist, in short every owner of property, was considered an enemy of the working masses. This army recognized only one verdict—execution.

A great gulf existed between Makhno army and the generally well-to-do Mennonite population, who had sympathized with the Germans during the occupation after 1917. This accounts for the severe suffering endured at the hands of the bandits by this group. When in the late summer of 1919 Batyko Makhno (Little Father Makhno, as his devoted adherents called him) broke through the army front of the loyalists with General Denikin near Umany in the Western Ukraine, he stormed with his horses back into the Ukraine. From Gulyay-Pole, his home, he directed the reign of terror as long as it was safe for him there. In this region there were wealthy Mennonite landowners on whose estates Makhno in his youth had been a cattle herder. The Makhno troops preferred to stay in the Mennonite villages, and stole great quantities of horses, wagons, produce, clothes, and whatever they could carry with them. Local bandits united with this army to take their share in the loot of furniture, agricultural machinery, etc. What they could not take away they simply destroyed.

All the Mennonite colonies which had the misfortune of being under the temporary yoke of Makhno had very difficult experiences. The greatest sufferings, however, were experienced by the settlements Borzenkovo, Zagradovka, and Chortitza with its daughter settlement of Nikolaipol. Two hundred forty names appear on a list of November 1919 of those murdered in Zagradovka. In Borzenkovo in the village of Ebenfeld alone 63 persons were murdered, and in Steinbach of the same settlement 58 persons. The army stationed in the Chortitza settlement 21 September-22 December 1919 (the Mennonites had already left the island of Chortitza at this time), inflicted great suffering. There was hardly a village that was not mourning at least several who had been murdered by the band (see Chortitza). In the village of Eichendorf in the Nikolaipol settlement 81 men and 4 women were murdered during the night of 26 November 1919. With the other villages, such as Hochfeld, Petersdorf, and Nikolaipol, the number murdered exceeds 100. It must be added, however, that the murders in the Nicolaipol settlement were committed mostly by local bands rather than the Makhno army. The Self-Defense Corps (Selbstschutz), which had been organized and drilled by German occupation army officers before the withdrawal of the German troops, was ineffectual in a military sense and only provoked worse reprisals.

In addition to the violence committed by the Makhno troops, an epidemic of typhus broke out among them affecting over half of the troops, including Makhno himself. Since these troops were lodging in the Mennonite homes, scattering a vast amount of vermin, practically the entire adult population of the Chortitza settlement contracted the disease. As many as 11-15 per cent of the colony's population died. These were with few exceptions all adults.

The ideal Anarchists (the Russian noble Peter Kropotkin may be considered the father of Russian Anarchism) remained aloof from this movement and therefore it had no foundation upon which to build its future. The result was that it deteriorated into banditry such as Russian history had experienced in adventurers like Pugachev or Stenka Razin. Makhno was frequently wounded in battle and finally fled to Rumania and from there to Poland and finally to Paris. He died in Paris in 1934.

Bibliography

Arshinov, Petr. History of the Makhnovist movement, 1918-1921. Detroit: Black & Red, 1974.

Lohrenz, Gerhard. Sagradowka: die Geschichte einer mennonitischen Ansiedlung im Süden Russlands. Rosthem, SK: Echo, 1947.

Lohrenz, Gerhard. Zagradovka: history of a Mennonite settlement in southern Russia. Winnipeg : CMBC Publications, 2000.

Nestor Makhno and the Eichenfeld Massacre: A Civil War Tragedy in a Ukrainian Mennonite Village, compiled, edited, translated and with an introduction and analysis by Harvey L. Dyck, John R. Staples and John B. Toews. Kitchener, ON: Pandora Press, 2004.

Neufeld, Dietrich. A Russian dance of death: revolution and civil war in the Ukraine. Winnipeg : Hyperion Press, 1980.

Patterson, Sean. Makhno and Memory: Anarchist and Mennonite Narratives of Ukraine's Civil War, 1917-1921. Winnipeg, Manitoba: University of Manitoba Press, 2020.

Peters, Victor. Nestor Makhno: The Life of an Anarchist." Winnipeg, MB: Echo Books, 1970.

Smith, C. Henry. The Story of the Mennonites. Newton, KS, 1950.

Sysyn, Frank. "Nestor Makhno and the Ukrainian Revolution" in The Ukraine: 1917-1921, a study in revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1977: 271-304.

Toews, Heinrich. Eichenfeld-Dubowka: ein Tatsachenbericht aus der Tragödie des Deutschtums in der Ukraine. Karlsruhe I.B. :H. Schneider, [1938].

| Author(s) | John G Rempel |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1957; 2024 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Rempel, John G. "Makhno, Nestor (1888-1934)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1957; 2024. Web. 22 Nov 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Makhno,_Nestor_(1888-1934)&oldid=179177.

APA style

Rempel, John G. (1957; 2024). Makhno, Nestor (1888-1934). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 22 November 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Makhno,_Nestor_(1888-1934)&oldid=179177.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 3, pp. 430-431. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.