Difference between revisions of "Jost, Ursula (d. 1532/39)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

SamSteiner (talk | contribs) |

SamSteiner (talk | contribs) m (Text replace - "Harrisonburg, Virginia, and Kitchener, Ontario," to "Harrisonburg, Virginia,") |

||

| (8 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

__TOC__ | __TOC__ | ||

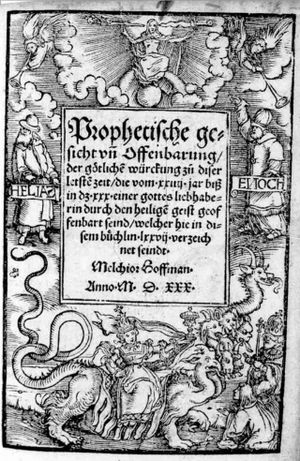

| + | [[File:Jost Ursula.jpg|300px|thumbnail|''Title page of Prophetische Gesicht unn Offenbarung. Source: [http://www.bsb-muenchen.de/ Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München], Rar. 4109#Beibd.6 , titlepage'']] | ||

Ursula Jost (active c. 1524-1532, died between 1532 and 1539) was a [[Melchiorites|Melchiorite]] prophet and visionary who lived in [[Strasbourg (Alsace, France)|Strasbourg]] during the early years of the Reformation. Her husband, [[Jost, Lienhard (16th century)|Lienhard Jost]], was also a prophet and visionary. The two lived in the environs of Strasbourg in either Krutenau or [[Illkirch-Graffenstaden (Alsace, France)|Illkirch]] and had at least eight children, the eldest of whom was named Elisabeth. Ursula began experiencing visions in late 1524, by which point Lienhard's prophetic experiences had already begun and he had been briefly confined in an asylum as a result. She received her longest series of visions in 1525; the visions then ceased, with one exception, until 1529, and they continued with some regularity until at least 1532. The exact date of Ursula’s death is not known, but it was no later than 1539, by which point Lienhard had remarried a woman named Agnes. | Ursula Jost (active c. 1524-1532, died between 1532 and 1539) was a [[Melchiorites|Melchiorite]] prophet and visionary who lived in [[Strasbourg (Alsace, France)|Strasbourg]] during the early years of the Reformation. Her husband, [[Jost, Lienhard (16th century)|Lienhard Jost]], was also a prophet and visionary. The two lived in the environs of Strasbourg in either Krutenau or [[Illkirch-Graffenstaden (Alsace, France)|Illkirch]] and had at least eight children, the eldest of whom was named Elisabeth. Ursula began experiencing visions in late 1524, by which point Lienhard's prophetic experiences had already begun and he had been briefly confined in an asylum as a result. She received her longest series of visions in 1525; the visions then ceased, with one exception, until 1529, and they continued with some regularity until at least 1532. The exact date of Ursula’s death is not known, but it was no later than 1539, by which point Lienhard had remarried a woman named Agnes. | ||

| − | Lienhard and Ursula, along with Barbara Rebstock, formed part of a circle of prophets that coalesced around [[Hoffman, Melchior (ca. 1495-1544?)|Melchior Hoffman]] after he arrived in Strasbourg in 1529. Hoffman relied on these prophets to legitimate his apostolic ministry, and he in turn bolstered their authority and promulgated their visions and prophecies within Melchiorite Anabaptist circles. Lienhard and Ursula were both illiterate and thus unable to produce written copies of their visions without assistance, and Hoffman provided this assistance on more than one occasion. He first produced an edition of Ursula’s visions in 1530, in which he identified her only as an anonymous ''gottesliebhaberin'' (lover of God). This edition, entitled ''Prophetische Gesicht unn Offenbarung der Götlichen Würckung zu diser Letsten Zeit (Prophetic Visions and Revelation of the Works of God in these End Times''), was printed in Strasbourg by Balthasar Beck, who also served as a printer for [[Schwenckfeld, Caspar von (1489-1561)|Caspar Schwenckfeld]] and [[Franck, Sebastian (1499-1543)|Sebastian Franck]]. It contained 77 of Ursula’s visions, arranged primarily in chronological order, as well as a foreword by Melchior Hoffman. Hoffman also produced a second edition of Ursula’s visions along with a copy of Lienhard’s visions, printed in Deventer in 1532 by Albert Paffraet (who later served as a printer for [[David Joris (ca. 1501-1556)|David Joris]]). This edition (until recently thought not to have survived, but recently rediscovered by Jonathan Green in the Austrian National Library in Vienna) also contained 29 new visions dated between 1530 and 1532. The Josts’ visions found a ready audience among Hoffman’s followers in the [[Netherlands]], as Hoffman’s associate Cornelis Poldermann confirmed to the Strasbourg magistracy in 1533. | + | Lienhard and Ursula Jost, along with Barbara Rebstock, formed part of a circle of prophets that coalesced around [[Hoffman, Melchior (ca. 1495-1544?)|Melchior Hoffman]] after he arrived in Strasbourg in 1529. Hoffman relied on these prophets to legitimate his apostolic ministry, and he in turn bolstered their authority and promulgated their visions and prophecies within Melchiorite Anabaptist circles. Lienhard and Ursula were both illiterate and thus unable to produce written copies of their visions without assistance, and Hoffman provided this assistance on more than one occasion. He first produced an edition of Ursula’s visions in 1530, in which he identified her only as an anonymous ''gottesliebhaberin'' (lover of God). This edition, entitled ''Prophetische Gesicht unn Offenbarung der Götlichen Würckung zu diser Letsten Zeit (Prophetic Visions and Revelation of the Works of God in these End Times''), was printed in Strasbourg by Balthasar Beck, who also served as a printer for [[Schwenckfeld, Caspar von (1489-1561)|Caspar Schwenckfeld]] and [[Franck, Sebastian (1499-1543)|Sebastian Franck]]. It contained 77 of Ursula’s visions, arranged primarily in chronological order, as well as a foreword by Melchior Hoffman. Hoffman also produced a second edition of Ursula’s visions along with a copy of Lienhard’s visions, printed in Deventer in 1532 by Albert Paffraet (who later served as a printer for [[David Joris (ca. 1501-1556)|David Joris]]). This edition (until recently thought not to have survived, but recently rediscovered by Jonathan Green in the Austrian National Library in Vienna) also contained 29 new visions dated between 1530 and 1532. The Josts’ visions found a ready audience among Hoffman’s followers in the [[Netherlands]], as Hoffman’s associate Cornelis Poldermann confirmed to the Strasbourg magistracy in 1533. |

Ursula’s visions do not always follow a coherent theological agenda—-she frequently shared visions without being sure of their interpretation herself—-but several themes emerge, including the sovereignty of God, the wrath of God (particularly against wealthy ecclesiastical oppressors), and human participation in salvation (through response to God’s offer of salvation and through good works). Moreover, although the extent of Ursula’s religious education is unknown—-it was certainly limited by her illiteracy—-she nevertheless evinced a basic understanding of important Christian theological concepts (in particular the Trinity) and selected biblical imagery and references from Exodus to the [[Sermon on the Mount]] to Revelation. Her visions were influential in Melchiorite circles for the first few years after their publication, as Hoffman accorded them (as well as Lienhard’s prophecies) an authority equal to that of the Old Testament prophets. However, as Hoffman’s influence waned among the Dutch and North German Melchiorites after his 1533 imprisonment in Strasbourg (which lasted until his death in 1544), the influence of the Josts and the other Strasbourg prophets appears to have diminished as well, though they remained important figures in Melchiorite circles in Strasbourg itself until the Strasbourg Melchiorites returned to the Reformed church in 1539. | Ursula’s visions do not always follow a coherent theological agenda—-she frequently shared visions without being sure of their interpretation herself—-but several themes emerge, including the sovereignty of God, the wrath of God (particularly against wealthy ecclesiastical oppressors), and human participation in salvation (through response to God’s offer of salvation and through good works). Moreover, although the extent of Ursula’s religious education is unknown—-it was certainly limited by her illiteracy—-she nevertheless evinced a basic understanding of important Christian theological concepts (in particular the Trinity) and selected biblical imagery and references from Exodus to the [[Sermon on the Mount]] to Revelation. Her visions were influential in Melchiorite circles for the first few years after their publication, as Hoffman accorded them (as well as Lienhard’s prophecies) an authority equal to that of the Old Testament prophets. However, as Hoffman’s influence waned among the Dutch and North German Melchiorites after his 1533 imprisonment in Strasbourg (which lasted until his death in 1544), the influence of the Josts and the other Strasbourg prophets appears to have diminished as well, though they remained important figures in Melchiorite circles in Strasbourg itself until the Strasbourg Melchiorites returned to the Reformed church in 1539. | ||

| − | + | Ursula Jost’s visions began to garner renewed interest among scholars of Anabaptism in the latter part of the 20th century. Klaus Deppermann’s 1979 biography of Melchior Hoffman (translated into English in 1987) included a substantial section on Ursula, Lienhard, and the other Melchiorite prophets in Strasbourg. Deppermann took a negative view of the Josts’ influence on Hoffman and on the Dutch Melchiorites. In Deppermann’s depiction, Ursula emerged as an angry, even bloodthirsty, woman who stoked Hoffman’s [[apocalypticism]] and gave it a militant edge. Conversely, Lois Barrett’s 1992 doctoral dissertation situated Ursula within the broader Christian apocalyptic visionary tradition. She directly opposed Deppermann’s portrayal of Ursula and argued that Ursula’s work represented an example of an Anabaptist apocalyptic theology that was intimately connected with a pacifist Anabaptist ethic. Most recently, Christina Moss’ 2013 MA thesis argued that Ursula’s visions did not entirely fit either portrayal and that, while she certainly expected God to violently punish the wicked, her views on whether and to what extent the elect ought to participate in said punishment were unclear. Further work remains to be done on Ursula, her role within 16th century Anabaptism, and her legacy, particularly in light of the rediscovery of the Lienhard’s visions and the second edition of her visions. Certainly, Ursula’s writings provide a fascinating glimpse into the spiritual life of 16th century Anabaptist peasant woman. | |

= Bibliography = | = Bibliography = | ||

Barrett, Lois. “Wreath of Glory: Ursula’s Prophetic Visions in the Context of Reformation | Barrett, Lois. “Wreath of Glory: Ursula’s Prophetic Visions in the Context of Reformation | ||

| Line 23: | Line 24: | ||

Strossburg''. Ed. Melchior Hoffman. Deventer: Albertus Paffraet, 1532. (Available at the | Strossburg''. Ed. Melchior Hoffman. Deventer: Albertus Paffraet, 1532. (Available at the | ||

Austrian National Library in Vienna. Also contains a second edition of Ursula’s visions | Austrian National Library in Vienna. Also contains a second edition of Ursula’s visions | ||

| − | entitled ''Eyn Wore Prophettin zu disser Letzsten Zeitt''.) | + | entitled ''Eyn Wore Prophettin zu disser Letzsten Zeitt''.) Available in full electronic text at http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ169334206. |

Jost, Ursula. ''Prophetische Gesicht un(n) Offenbarung der Gotliche(n) Wurckung zu diser | Jost, Ursula. ''Prophetische Gesicht un(n) Offenbarung der Gotliche(n) Wurckung zu diser | ||

| Line 54: | Line 55: | ||

= Original Article from Mennonite Encyclopedia = | = Original Article from Mennonite Encyclopedia = | ||

| − | By Nanne van ver Zijpp. Copied by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia | + | By Nanne van ver Zijpp. Copied by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from ''Mennonite Encyclopedia'', Vol. 4, p. 790. All rights reserved. |

| + | |||

Ursula, the wife of [[Jost, Lienhard (16th century)|Lienhard Jost]] at [[Strasbourg (Alsace, France)|Strasbourg]], a "prophetess" and like her husband devoted follower of [[Hoffman, Melchior (ca. 1495-1544?) |Melchior Hoffman]], who was greatly influenced by her and ranked her prophecies with those of Isaiah and Jeremiah. | Ursula, the wife of [[Jost, Lienhard (16th century)|Lienhard Jost]] at [[Strasbourg (Alsace, France)|Strasbourg]], a "prophetess" and like her husband devoted follower of [[Hoffman, Melchior (ca. 1495-1544?) |Melchior Hoffman]], who was greatly influenced by her and ranked her prophecies with those of Isaiah and Jeremiah. | ||

== Bibliography == | == Bibliography == | ||

| Line 61: | Line 63: | ||

Hulshof, A. <em>Geschiedenis van de Doopsgezinden te Straatsburg . . .</em> Amsterdam, 1905: 117-23. | Hulshof, A. <em>Geschiedenis van de Doopsgezinden te Straatsburg . . .</em> Amsterdam, 1905: 117-23. | ||

{{GAMEO_footer|hp=|date=May 2016|a1_last=Moss|a1_first=Christina|a2_last= |a2_first= }} | {{GAMEO_footer|hp=|date=May 2016|a1_last=Moss|a1_first=Christina|a2_last= |a2_first= }} | ||

| + | [[Category:Persons]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Sixteenth Century Anabaptist Leaders]] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:59, 14 January 2017

Ursula Jost (active c. 1524-1532, died between 1532 and 1539) was a Melchiorite prophet and visionary who lived in Strasbourg during the early years of the Reformation. Her husband, Lienhard Jost, was also a prophet and visionary. The two lived in the environs of Strasbourg in either Krutenau or Illkirch and had at least eight children, the eldest of whom was named Elisabeth. Ursula began experiencing visions in late 1524, by which point Lienhard's prophetic experiences had already begun and he had been briefly confined in an asylum as a result. She received her longest series of visions in 1525; the visions then ceased, with one exception, until 1529, and they continued with some regularity until at least 1532. The exact date of Ursula’s death is not known, but it was no later than 1539, by which point Lienhard had remarried a woman named Agnes.

Lienhard and Ursula Jost, along with Barbara Rebstock, formed part of a circle of prophets that coalesced around Melchior Hoffman after he arrived in Strasbourg in 1529. Hoffman relied on these prophets to legitimate his apostolic ministry, and he in turn bolstered their authority and promulgated their visions and prophecies within Melchiorite Anabaptist circles. Lienhard and Ursula were both illiterate and thus unable to produce written copies of their visions without assistance, and Hoffman provided this assistance on more than one occasion. He first produced an edition of Ursula’s visions in 1530, in which he identified her only as an anonymous gottesliebhaberin (lover of God). This edition, entitled Prophetische Gesicht unn Offenbarung der Götlichen Würckung zu diser Letsten Zeit (Prophetic Visions and Revelation of the Works of God in these End Times), was printed in Strasbourg by Balthasar Beck, who also served as a printer for Caspar Schwenckfeld and Sebastian Franck. It contained 77 of Ursula’s visions, arranged primarily in chronological order, as well as a foreword by Melchior Hoffman. Hoffman also produced a second edition of Ursula’s visions along with a copy of Lienhard’s visions, printed in Deventer in 1532 by Albert Paffraet (who later served as a printer for David Joris). This edition (until recently thought not to have survived, but recently rediscovered by Jonathan Green in the Austrian National Library in Vienna) also contained 29 new visions dated between 1530 and 1532. The Josts’ visions found a ready audience among Hoffman’s followers in the Netherlands, as Hoffman’s associate Cornelis Poldermann confirmed to the Strasbourg magistracy in 1533.

Ursula’s visions do not always follow a coherent theological agenda—-she frequently shared visions without being sure of their interpretation herself—-but several themes emerge, including the sovereignty of God, the wrath of God (particularly against wealthy ecclesiastical oppressors), and human participation in salvation (through response to God’s offer of salvation and through good works). Moreover, although the extent of Ursula’s religious education is unknown—-it was certainly limited by her illiteracy—-she nevertheless evinced a basic understanding of important Christian theological concepts (in particular the Trinity) and selected biblical imagery and references from Exodus to the Sermon on the Mount to Revelation. Her visions were influential in Melchiorite circles for the first few years after their publication, as Hoffman accorded them (as well as Lienhard’s prophecies) an authority equal to that of the Old Testament prophets. However, as Hoffman’s influence waned among the Dutch and North German Melchiorites after his 1533 imprisonment in Strasbourg (which lasted until his death in 1544), the influence of the Josts and the other Strasbourg prophets appears to have diminished as well, though they remained important figures in Melchiorite circles in Strasbourg itself until the Strasbourg Melchiorites returned to the Reformed church in 1539.

Ursula Jost’s visions began to garner renewed interest among scholars of Anabaptism in the latter part of the 20th century. Klaus Deppermann’s 1979 biography of Melchior Hoffman (translated into English in 1987) included a substantial section on Ursula, Lienhard, and the other Melchiorite prophets in Strasbourg. Deppermann took a negative view of the Josts’ influence on Hoffman and on the Dutch Melchiorites. In Deppermann’s depiction, Ursula emerged as an angry, even bloodthirsty, woman who stoked Hoffman’s apocalypticism and gave it a militant edge. Conversely, Lois Barrett’s 1992 doctoral dissertation situated Ursula within the broader Christian apocalyptic visionary tradition. She directly opposed Deppermann’s portrayal of Ursula and argued that Ursula’s work represented an example of an Anabaptist apocalyptic theology that was intimately connected with a pacifist Anabaptist ethic. Most recently, Christina Moss’ 2013 MA thesis argued that Ursula’s visions did not entirely fit either portrayal and that, while she certainly expected God to violently punish the wicked, her views on whether and to what extent the elect ought to participate in said punishment were unclear. Further work remains to be done on Ursula, her role within 16th century Anabaptism, and her legacy, particularly in light of the rediscovery of the Lienhard’s visions and the second edition of her visions. Certainly, Ursula’s writings provide a fascinating glimpse into the spiritual life of 16th century Anabaptist peasant woman.

Bibliography

Barrett, Lois. “Wreath of Glory: Ursula’s Prophetic Visions in the Context of Reformation and Revolt in Southwestern Germany, 1524-1530.” PhD diss.: The Union Institute, 1992.

Deppermann, Klaus. Melchior Hoffmann: Social Unrest and Apocalyptic Visions in the Age of Reformation. Edited by Benjamin Drewery. Translated by Malcom Wren. Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1987: 203-213.

Green, Jonathan. “The Lost Book of the Strasbourg Prophets: Orality, Literacy, and Enactment in Lienhard Jost’s Visions.” The Sixteenth Century Journal 46:2 (Summer 2015): 313- 330.

Jost, Lienhard. Ein Worhafftige Hohe und Feste Prophecey des Linhart Josten van Strossburg. Ed. Melchior Hoffman. Deventer: Albertus Paffraet, 1532. (Available at the Austrian National Library in Vienna. Also contains a second edition of Ursula’s visions entitled Eyn Wore Prophettin zu disser Letzsten Zeitt.) Available in full electronic text at http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ169334206.

Jost, Ursula. Prophetische Gesicht un(n) Offenbarung der Gotliche(n) Wurckung zu diser letste Zeit. Ed. Melchior Hoffman. Strasbourg: Balthasar Beck, 1530. (Available at the Bavarian State Library in Munich.)

Krebs, Manfred and Hans Georg Rott. Quellen zur Geschichte der Täufer. Vol. 7. Elsass I. Teil: Stadt Straßburg 1522-1532. Gütersloh: Gerd Mohn, 1959.

Krebs, Manfred and Hans Georg Rott. Quellen zur Geschichte der Täufer. Vol. 8. Elsass II. Teil: Stadt Straßburg 1533-1535. Gütersloh: Gerd Mohn, 1960.

Lienhard, Marc, Stephen F. Nelson, and Hans Georg Rott. Quellen zur Geschichte der Täufer. Vol. 15. Elsass III. Teil: Stadt Straßburg 1536-1542. Gütersloh: Gerd Mohn, 1986.

Moss, Christina. “An Examination of the Visions of Ursula Jost in the Context of Early Anabaptism and Late Medieval Christianity.” MA Thesis: University of Waterloo, 2013.

Moss, Christina. “Marriage as Spiritual Partnership in Sixteenth-Century Strasbourg: The Case of Lienhard and Ursula Jost.” In Newberry Essays in Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Volume 9: Selected Proceedings of the Newberry Center for Renaissance Studies 2015 Multidisciplinary Graduate Student Conference. Edited by Karen Christianson and Andrew K. Epps. Chicago: The Newberry Library, 2015: 83-94. http://www.newberry.org/sites/default/files/textpage-attachments/2015Proceedings.pdf

Snyder, C. Arnold and Linda H. Hecht, eds., Profiles of Anabaptist Women: Sixteenth- Century Reforming Pioneers. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1996: 273-287.

Original Article from Mennonite Encyclopedia

By Nanne van ver Zijpp. Copied by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 4, p. 790. All rights reserved.

Ursula, the wife of Lienhard Jost at Strasbourg, a "prophetess" and like her husband devoted follower of Melchior Hoffman, who was greatly influenced by her and ranked her prophecies with those of Isaiah and Jeremiah.

Bibliography

Cramer, Samuel and Fredrik Pijper. Bibliotheca Reformatoria Neerlandica, 10 vols. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1903-1914: v. VII, 125 ff.

Hulshof, A. Geschiedenis van de Doopsgezinden te Straatsburg . . . Amsterdam, 1905: 117-23.

| Author(s) | Christina Moss |

|---|---|

| Date Published | May 2016 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Moss, Christina. "Jost, Ursula (d. 1532/39)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. May 2016. Web. 22 Nov 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Jost,_Ursula_(d._1532/39)&oldid=143139.

APA style

Moss, Christina. (May 2016). Jost, Ursula (d. 1532/39). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 22 November 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Jost,_Ursula_(d._1532/39)&oldid=143139.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.