Difference between revisions of "Dirk Philips (1504-1568)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m (Text replace - "</em><em>" to "") |

m (Added categories.) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

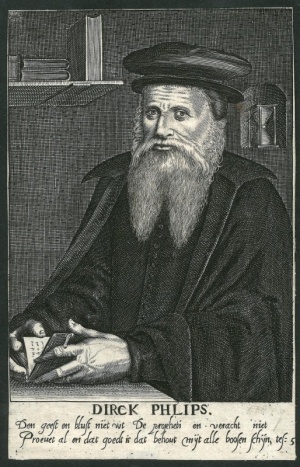

| − | [[File:Philips.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Source: [http://dpc.uba.uva.nl/cgi/i/image/image-idx Bibliotheek van de Universiteit van Amsterdam: Doopsgezinde Prenten]'']] | + | [[File:Philips.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Dirk Philips (1504-1568).<br /> |

| + | Source: [http://dpc.uba.uva.nl/cgi/i/image/image-idx Bibliotheek van de Universiteit van Amsterdam: Doopsgezinde Prenten]'']] | ||

Dirk Philips (Philipsz, Philopszoon, Filips) (1504-1568) was the son of a Dutch priest. He became a Franciscan monk. As a man of good education he had a command of Latin and Greek, and also knew some Hebrew. It is doubtful that he wrote in French his booklet on the ban and avoidance, which he published in the French language. It is possible that he studied at a university. [[Schijn, Herman (1662-1727)|H. Schijn]] (<em>Hist. Menn. plenior deductio, </em> 1729, p. 186) calls him a learned man, more learned than [[Menno Simons (1496-1561)|Menno Simons]]. He was not acquainted with [[Luther, Martin (1483-1546)|Luther's]] writings. | Dirk Philips (Philipsz, Philopszoon, Filips) (1504-1568) was the son of a Dutch priest. He became a Franciscan monk. As a man of good education he had a command of Latin and Greek, and also knew some Hebrew. It is doubtful that he wrote in French his booklet on the ban and avoidance, which he published in the French language. It is possible that he studied at a university. [[Schijn, Herman (1662-1727)|H. Schijn]] (<em>Hist. Menn. plenior deductio, </em> 1729, p. 186) calls him a learned man, more learned than [[Menno Simons (1496-1561)|Menno Simons]]. He was not acquainted with [[Luther, Martin (1483-1546)|Luther's]] writings. | ||

| Line 77: | Line 78: | ||

Menno Simons.<em> Opera Omnia Theologica. </em> 1681. | Menno Simons.<em> Opera Omnia Theologica. </em> 1681. | ||

= Additional Information = | = Additional Information = | ||

| − | + | === Electronic Resources === | |

| + | Philip, Dietrich. <em>Enchirdion: oder Handbüchlein von der Christlichen lehre und religion zum dienst von allen liebhabern der Wahreit (durch die Gnade Gottes) aus der Heiligen Schrift gemacht, mit einem schönen und fasslichen register</em>. Lancaster, PA: Gedruckt bey Joseph Ehrenfried, 1811. [http://hdl.handle.net/2027/njp.32101063702615 Full Text]. | ||

{{GAMEO_footer|hp=Vol. 2, pp. 65-66; vol. 5, p. 234|date=1956|a1_last=Zijpp|a1_first=Nanne van der|a2_last= |a2_first= }} | {{GAMEO_footer|hp=Vol. 2, pp. 65-66; vol. 5, p. 234|date=1956|a1_last=Zijpp|a1_first=Nanne van der|a2_last= |a2_first= }} | ||

| + | [[Category:Persons]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Sixteenth Century Anabaptist Leaders]] | ||

Revision as of 20:34, 29 November 2014

Source: Bibliotheek van de Universiteit van Amsterdam: Doopsgezinde Prenten

Dirk Philips (Philipsz, Philopszoon, Filips) (1504-1568) was the son of a Dutch priest. He became a Franciscan monk. As a man of good education he had a command of Latin and Greek, and also knew some Hebrew. It is doubtful that he wrote in French his booklet on the ban and avoidance, which he published in the French language. It is possible that he studied at a university. H. Schijn (Hist. Menn. plenior deductio, 1729, p. 186) calls him a learned man, more learned than Menno Simons. He was not acquainted with Luther's writings.

At the end of 1533 Dirk joined the Anabaptist brotherhood. He was baptized at Leeuwarden in Friesland, by Pieter Houtzager, and was soon afterward, presumably early in 1534, "upon the wish of the brethren" ordained an elder by the laying on of the hands of his own brother Obbe Philips at "Den Dam," i.e., Appingedam, in the Dutch province of Groningen. He was soon a leader; in 1537 he was named as one of the outstanding Anabaptist leaders; he took part in the most important events of the following years, and nearly always was present at the conferences of the elders, as in Goch in 1547, where Adam Pastor was banned, and in 1554 in Wismar among the seven elders, who formulated an agreement on a number of contested points. Like Obbe and Menno he was an opponent of the Münsterite doctrines. Against Rothmann's Restitution (1534) he wrote his booklet, Van de geestelijcke Restitution (On the Spiritual Restitution).

At first Dirk worked in the Netherlands, then in East Friesland, Mecklenburg, Holstein, and Prussia. But he must have gone to the Netherlands on several occasions; about 1561 he baptized several persons in Utrecht and celebrated communion with about 20 brethren (DB 1903, 21 f.). We are told that the meeting lasted from four in the morning until seven in the evening; probably not because they needed so much time, but because they wanted to enter and leave the house under cover of darkness. Dirk is described on that occasion as "an old man, not very tall, with a gray beard and white hair." After 1550 his home was at Danzig, where a number of Dutch Mennonites had already located.

Dirk Philips is without doubt the leading theologian and dogmatician among the Dutch and North German Mennonites of that time. He is more systematic than Menno, though of course also more severe and one-sided. Like Menno he preached the doctrine of nonresistance, though there is not much in his writings on this subject. He shares Menno's conception of the Incarnation. Against Adam Pastor he upholds the doctrine of the Trinity. In opposition to his brother Obbe he always put much stress on the visible church, which should preserve itself from the world without spot or wrinkle. In the interest of protecting the brotherhood he demands a strict application of the ban and the subsequent avoidance. The open sinners shall be expelled from the congregation if they do not show genuine repentance; they are to be shunned in daily life, because the church of God, which consists of the elect, must be pure and holy. The bride of Christ dare not forsake her Bridegroom and yield herself to the world and the flesh.

In his book on the church he names seven ordinances of the church of God: pure doctrine, Scriptural use of the sacraments, washing the feet of the saints, separation (ban and avoidance), the command of love, obedience to the commands of Christ, suffering and persecution. On the whole it cannot be denied that there is in Dirk Philips' theology a certain moralism and legalism. He writes better than Menno, but he has less agreeableness, friendliness, and charm. He was a strict, indeed an obstinate person. This can best be seen in the disputes between him and Leenaert Bouwens. Even considering that the question at issue concerns the pure church of Christ and that this ideal requires a measure of severity, nevertheless the sad consequences of this strict banning and partisanship are without question to be reckoned against the obstinate and proud elder, Dirk Philips. Already in 1565 Leenaert Bouwens had been suspended from his office. In 1567 Dirk journeyed from Danzig to Emden. Then the division occurred: Dirk sided with the Flemish, who at once banned the Frisians, while the Frisians, whom Leenaert had joined, on their side banned the Flemish. Dirk was also banned (8 July 1567), but did not let it trouble him, because he no longer considered Leenaert and the Frisians as members of the church of God. (Kühler, Geschiedenis I, 395-426.)

In the next year Dirk died at Het Falder near Emden, after he had completed his booklet on Christian marriage on 7 March 1568.

Although Dirk Philips surpassed the other elders in knowledge and was a good writer and an eloquent and influential man, he was nevertheless inferior to Menno Simons, with whom he had worked so many years and upon whom he exerted a certain influence in his later years when the severe banning took its course. It is unpleasant to note that Menno's name does not once occur in Dirk's writings. When in the first half of the 17th century the practice of the ban became more lenient among the Dutch and North German Mennonites, the interest in Dirk Philips also waned; his writings are held in high esteem by the Old Order Amish because they advocate the ban and avoidance.

Dirk Philips spread his views in numerous booklets. At the end of his life he collected his writings that had been published, several of which are still extant in their various editions, and published them in a single volume. This is the Enchiridion oft Hantboecxken van de Christelijcke Leere, ... 1564. The "little" handbook (it contains almost 650 pages!) contains the following writings: Confession of Faith, Concerning the Incarnation, Concerning the True Knowledge of Jesus Christ, Apologia, the Call of the Preacher, Loving Admonition (on the ban), Concerning the True Knowledge of God, Exposition of the Tabernacle of Moses, Concerning the New Birth, Concerning Spiritual Restoration, Three Thorough Admonitions, Table of Contents.

In addition he wrote: Verantwoordinghe ende Refutation op twee Sendtbrieven Sebastiani Franck (printed in 1567, not extant, and 1619); Cort doch grondtlick Verhael (concerning the quarrels between the Flemish and Frisians, printed in 1567); Van die Echt der Christenen (printed in 1569, 1602, 1634, 1644, and perhaps other editions) ; and the tract left at his death on the ban and avoidance, which was translated from the French and printed in 1602.

Of the Enchiridion there are in the Dutch language editions of 1564, 1578, 1579, 1600, and 1627. A French edition of 1626 (in the same volume with some writings of Menno Simons and others), German editions in 1715 and Basel in 1802; Lancaster, 1811; Elkhart, 1872 (this and the following German editions include the writings on marriage and on the ban); Scottdale, 1917, Berne, IN, 1958; English edition, Elkhart, IN, 1910; Berne, IN, 1958 and Aylmer, ON, 1966.

Two hymns from the pen of Dirk Philips have been preserved, and were adopted into the old Dutch hymnals of the Mennonites.

F. Pijper edited a complete edition of all the writings (including letters and hymns) of Dirk Philips (BRN X). An English translation of Dirk's writings are included in the Classics of the Radical Reformation series published by Herald Press, Scottdale, PA.

Bibliography

Bibliotheca Reformatoria Neerlandica, 10 vols: Introduction. The Hague, 1914.

Doopsgezinde Bijdragen (1864): 136; (1867): 59, 62 f.; (1873): 61; (1876): 26 ff., 38; (1881): 75; (1884): 2, 10, 15, 17, 20; (1887): 101 f.; (1893): 5, 12-14, 16, 50, 52-77, 88; (1894): 18-59 passim; (1903): 11, 21 f., 39, 41 f.; (1905): 106 ff.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. III, 368.

Hoop Scheffer, J. G. de. Inventaris der Archiefstukken berustende bij de Vereenigde Doopsgezinde Gemeente te Amsterdam, 2 vols. Amsterdam, 1883-1884: v. I, No. 620.

Krahn, Cornelius. Menno Simons. Karlsruhe, 1936: passim, see Index.

Schijn-Maatschoen, Uitvoeriger Verhandeling van de Geschiedenisse der Mennoniten II. Amsterdam, 1744: 32585.

Vos, K. Menno Simons. Leiden, 1914.

Vos, K. Groningen Volksalmanak. 1916: 131 f.; 136-42.

Selected Bibliography:

Balke, Willem. Calvin and the Anabaptist Radicals. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1981.

Beachy, Alvin J. "The Concept of Grace in the Radical Reformation." Mennonite Quarterly Review 36 (1962): 91-93.

Beachy, Alvin J. "The Grace of God in Christ as Understood by Five Major Anabaptist Writers." Mennonite Quarterly Review 37 (1963): 5-33.

Beachy, Alvin J. The Concept of Grace in the Radical Reformation. Nieuwkoop: B. De Graaf, 1977.

Beachy, Alvin J. "De herwaardering van Dirk Philips." Doopsgezinde Bijdragen , n.r. 7 (1981): 92-95.

Dirk Philipsz, Enchiridion, or Hand Book..., trans. A. B. Kolb. Aylmer, ON: Pathway Publishing Corp., 1966.

Doornkaat Koolman, J. ten. "The First Edition of Dirk Philips' Enchiridion." Mennonite Quarterly Review 38 (1964): 357-360.

Doornkaat Koolman, J. ten. Dirk Philips: Vriend en Medewerker van Menno Simons, 1504-1568. Haarlem: H. D. Tjeenk Willink en Zoon, 1964.

Dyck, Cornelius J. "The Christology of Dirk Philips," Mennonite Quarterly Review 31 (1957): 147-155.

Dyck, Cornelius J., William E. Keeney and Alvin J. Beachy. The Writings of Dirk Philips 1504-1568, Classics of the Radical Reformation, vol. 5. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1992.

Keeney, William E. "Dirk Philips' Life, Mennonite Quarterly Review 32 (1958): 171-191.

Keeney, William E. Dutch Anabaptist Thought and Practice, 1539-1564. Nieuwkoop: B. De Graaf, 1968.

Keeney, William E. "The Incarnation: A Central Theological Concept." in A Legacy of Faith, ed. Cornelius J. Dyck. Newton, 1962: 55-68.

Keeney, William E. "The Writings of Dirk Philips." Mennonite Quarterly Review 32 (1958): 298-306.

Keyser, Marja. Dirk Philips, 1504-1568. Nieuwkoop: B. De Graaf, 1975.

Mellink, A. F. Documenta Anabaptistica Neerlandica, Eerste Deel: Friesland en Groningen (1530-1550). Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1975.

Menno Simons. Opera Omnia Theologica. 1681.

Additional Information

Electronic Resources

Philip, Dietrich. Enchirdion: oder Handbüchlein von der Christlichen lehre und religion zum dienst von allen liebhabern der Wahreit (durch die Gnade Gottes) aus der Heiligen Schrift gemacht, mit einem schönen und fasslichen register. Lancaster, PA: Gedruckt bey Joseph Ehrenfried, 1811. Full Text.

| Author(s) | Nanne van der Zijpp |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1956 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Zijpp, Nanne van der. "Dirk Philips (1504-1568)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1956. Web. 12 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Dirk_Philips_(1504-1568)&oldid=127869.

APA style

Zijpp, Nanne van der. (1956). Dirk Philips (1504-1568). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 12 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Dirk_Philips_(1504-1568)&oldid=127869.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, pp. 65-66; vol. 5, p. 234. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.