Worship, Private

Private worship is the concern to make faith operative in daily life. It runs like a silver thread through the Mennonite story. As Kauffman and Harder point out in their book Anabaptists Four Centuries Later, "personal acts of Bible meditation, prayer and devotion are the religious practices usually conceived to be the well-spring of faithful living" (p. 96).

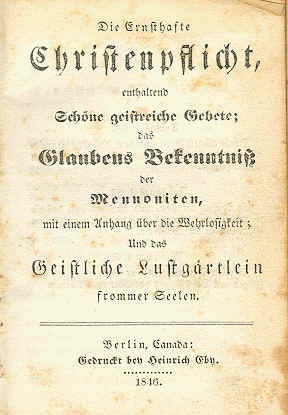

The beginnings of the Mennonite heritage of private worship are with the Anabaptists. Kauffman and Harder write, "Even with their emphases on corporate assembly and community, early Anabaptists didn't overlook the importance of the personal devotional discipline. One of their earliest documents admonished, 'Read the Psalter daily at home' " (CRR 1:44). Robert Friedman in his article on devotional literature concurs, saying, "The main devotional book of the Anabaptists and Mennonites was and still is, the Bible; all the rest are auxiliary to it." His article does, however, describe the auxiliary literature that was used and how it defines what was of importance to the Anabaptists of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. Books containing confessions (testimonies) of outstanding Anabaptists (some of them martyrs) were very popular for devotional reading through the ages, and were handed down to children and grandchildren. Then too, for their hymns, sermons, and devotional books, Anabaptists and Mennonites borrowed heavily from other traditions, e.g., Pietists, Moravians, and Brethren (Dunkers). The emphasis of Count Nicholas von Zinzendorf and the Moravians, for example, on Jesus as loving and kind, left its mark on Mennonites. The Mennonite and non-Mennonite sources of the Ernsthafte Christenpflicht, the first Mennonite prayer book (1708) are described in its article. Since 1984 selections from this prayer book are available in English under the title A devoted Christian's prayer book (Aylmer, Ont. and Lagrange, Ind.: Pathway Publishing Corporation). A new translation was done by Leonard Gross in 1997.

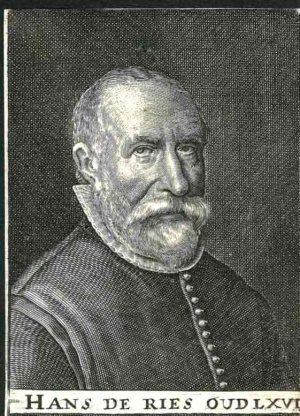

Anabaptists did not describe just how they carried on their private prayer nor give any evaluation of its depth and meaning. Something of the quality of Anabaptist private prayer can be inferred by noting how outsiders saw them. Georg Thormann, a Swiss Reformed pastor, in The Touchstone (1690) assured his readers that "it is not necessary to become an Anabaptist to be saved!" Hans de Ries was known for his fervent audible prayers which he must have prayed out of a life of meaningful private worship. It is also safe to assume that Anabaptist public worship reflected Anabaptist private worship and vice versa, in both meaning and form. As to form, Anabaptist worship was to be without embellishment and simple, so that form would not crowd God out. Silent prayer was the general practice until about the 18th or 19th century. Until the 20th century aspects of the traditional Christian calendar were followed. As to meaning, for Mennonites and Anabaptists to worship was to be in fellowship with the Divine, to have a repentant attitude, and to yield to God (Gelassenheit). It was also to take Jesus' life for one's personal example, to show opposition to evil, and to express love. These must certainly have been some of the expectations they brought also to their private worship.

Some sense of Mennonite private worship can also be inferred by taking note of what was happening in the world around them. The impact of their rural environment, wars and revolutions, revival meetings, and Pietism, shaped Mennonites in the 19th century and into the early 20th century. One of the tasks of prayer was to discern how best to live out their faith in the midst of these experiences.

Then came World Wars I and II with the options to do military, noncombatant, or alternative service. There were also greater opportunities in higher education and in world mission. These led to what later became the Women's Missionary and Service organization (MC) to publish a Monthly prayer cycle (1921) with the stated purpose of "encouraging intelligent and effectual prayer for missions in the Sunday school, sewing circles, prayer meetings, family worship and private prayer." Each page of the leaflet had a Bible verse such as Proverbs 15:8 or James 5:16 at the top and a particular prayer request for each day. On day 24, for example, participants were asked to pray for high school and college girls "that they may give us their new ideas and we may learn from them because the church needs them." On day 20 readers were asked to pray "that America will be worthy of being called a 'Christian nation.' " In 1935 a modest sheet entitled The voluntary prayer link was printed in Ontario. Its editor, L. J. Burkholder, wrote, "It will be my purpose to place a sheet in the hands of every person who will agree to use it as an aid in their regular devotions." For almost five years it collected both items for prayer and answers to prayer, both locally and from foreign fields. The General Sewing Circle (MC) again took up the task of calling people to prayer for missions in 1946 by publishing The daily prayer calendar. The first day of each month was to be prayer for the Mennonite Church "that she may receive an enlarged vision of her true mission in the world" and "that mothers and fathers in the church may have divine wisdom to lead their children in the way of the Lord." Four years later this booklet was enlarged to include a daily Bible reading, prayers for children, and suggested book lists for personal and family spiritual growth as well as specific prayer requests for missionaries, relief workers, those serving Mennonite institutions, the government, and the United Nations. It was then called The daily prayer guide. It, and its successor known as Voice, had and have a quiet but definite influence on the development and regularity of private worship in the church.

Interest in personal devotions kept growing. John R. Mumaw, General Secretary for the Mennonite Commission for Christian Education and Young People's work, wrote that "worship is a real necessity of the soul," and that "one of the vital aspects of Christian living is a consciousness of God's presence with us" (Worship in the home, ca. 1941). Likewise Ernest Bohn in his speech in 1947 at the sixth conference on "Mennonite Cultural Problems" links piety to the deepening concern for the Christian family. He says, "As we now come to the consideration of definite techniques of teaching religion in the home, may we suggest as number one, a pair of parents who have thoroughly committed themselves to Christ and his way of life."

By and large Mennonites see private worship as affecting daily living. Paul Erb, the editor of the Gospel herald (MC) during the 1940s and 1950s, judged reader interest in personal spiritual growth to be high. He ran a series entitled, "To be near to God," and printed numerous articles of this kind. Mennonite leaders as a whole in those decades and the ones to follow urged members to live as they pray and pray as they live. Christian living, including prayer, is to deal with the issues of the day: the meaning of nonconformity in the 1950s, of being Christian in relationships and making the church relevant in the 1960s, of being responsible politically and socially for peace and justice in the 1970s and 1980s, and of resisting the indulgence of the 1980s.

Included in Kauffman and Harder's profile of five Mennonite and Brethren in Christ denominations is a description of their devotionalism and sanctification. They found, for example, that 77 percent of respondents had a "sense of being loved by Christ," 71 percent "a sense of being tempted by the devil," and 72 percent "a feeling ... [of being] in the presence of God." Further, 77 percent of the subjects in the study as over against 75 percent of American Protestants who "generally pray at least once a week," prayed daily or more. Thirty-two percent, as over against 13 percent of American Protestants who "read the Bible at home," studied the Bible daily. Yet the authors concluded with the observation that "twentieth century Anabaptists have not been able to achieve fully a synthesis of the worshiping heart and the helping hand."

A person's concept of God and of God's desired responses from humans does affect private worship. The Dordrecht Confession's (1632) view of God as Eternal, Almighty, Creator of all things visible and invisible, at work in all, present for comfort and protection continues with Mennonites as a people scattered throughout the world. Contemporary American Mennonites, along with East Indian, African, and Japanese Mennonites frequently address God as Father. Members of Spanish-speaking Mennonite churches in Paraguay more often call God, "our Owner." Can it be that non-Western (in an ideological rather than a geographical sense) Mennonites know for a fact that in God alone exists all hope? North Americans who have lived abroad say that fellow Mennonites there seem to see prayer as central to living and are ready to speak to this. It appears that Mennonites worldwide want to respond to God in commitment and in obedience which is the fruit of love.

Mennonites continue to be influenced by and borrow from various other Christian groups. Beginning in the 1970s this is particularly true of the charismatic influence. One of the benefits which has come to the Mennonites through this is a deepening hunger for fellowship with God in prayer and Bible reading. In the hope of helping Mennonites "borrow" wisely, the Ministry of Spirituality Committee (MC) called a consultation in August of 1986 at Ashland, Ohio, to consider carefully six streams of spirituality which presently influence the church. The "streams" studied were charismatic, relational, feminist, Anabaptist, conservative evangelical, and contemplative. Over 70 persons attended and then spelled out what influences can be seen to contribute to a stronger Mennonite spirituality.

Interest in Christian spirituality (an intimate relationship between God and people which enables them to love God, follow Christ, and walk in the Spirit) continues strong within the denomination. The General Conference Mennonite Church also, in 1985, appointed a Spiritual Emphasis Committee to encourage the intentional giving of self to spiritual growth in private worship. Mennonite seminaries and colleges do include courses on the spiritual disciplines and private prayer, and report continuing interest in and sincere commitment to these studies.

Bibliography

Augsburger, A. Donald. "Parental Roles in the Development of Attitudinal Patterns in the Family Worship Experience." Thesis, Eastern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1956.

Bauman, Harold E. "The Family Aids Spiritual Maturity." Christian Living 7 (October 1960): 8-10.

Bohn, Ernest. " Religion in the Home" in Proceedings of the 6th Annual Conference on Mennonite Cultural Problems held at Goshen College, August 1-2, 1947: 87-94.

Christian family relationships, Proceedings of the Study Conference on Home Interests ... Held at Goshen College,. .. August 28-31, 1959 (Mennonite Commission for Christian Education, 1960), various articles.

Erb, Paul. Don't Park Here. Scottdale, 1962 in part IV.

Family worship (Scottdale, 1961-), a quarterly.

Friedmann, Robert. "Devotional Literature of the Mennonites in Danzig and East Prussia to 1800" Mennonite Quarterly Review 18 (1944): 162-73.

Friedmann, Robert. "Devotional Literature of the Swiss Brethren 1600-1800." Mennonite Quarterly Review 16 (1942): 199-220.

Friedmann, Robert. "Dutch Mennonite Devotional Literature from Peter Peters to Johannes Deknatel, 1625-1753." Mennonite Quarterly Review 25 (1951): 187-207.

Friedmann, Robert. Mennonite Piety Through the Centuries. Goshen: Mennonite Historical Society, 1949.

Friedmann, Robert. "Mennonite Prayer Books." Mennonite Quarterly Review 17 (1943): 179-206.

Harder, Leland, ed., The Sources of Swiss Anabaptism: the Grebel Letters and Related Documents, Classics of the Radical Reformation (CRR), vol. 4. Scottdale: Herald Press, 1985.

Kauffman, J. Howard and Leland Harder, eds. Anabaptists Four Centuries Later: a Profile of Five Mennonite and Brethren in Christ Denominations. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 1975.

Kauffman, Nelson E., ed. For Family Worship: a Series of Doctrinal Meditations Based on Scripture Selections for the Family Worship Hour. Scottdale, 1949.

Miller, Paul M. "Worship Among the Early Anabaptists" Mennonite Quarterly Review 30 (1956): 235-46.

Mumaw, John R. "Vital Experiences at the Family Altar" in Christian Ministry 5 (1952): 216-19.

Mumaw, John R. Worship in the Home. Scottdale: MPH, ca. 1941.

Our family worships ( Newton, 1961- ), a quarterly.

Papers at "The Mennonite Church Consultation on spirituality" at Ashland, Ohio, Aug. 1986 (Mennonite Board of Congregational Ministries [MCI).

Prayer Book for Earnest Christians: Die ernsthafte Christenpflicht, trans. and ed. by Leonard Gross. Scottdale: Herald Press, 1997.

"Spirituality reconsidered," a series of articles Gospel Herald (May, 1982).

Springer, Nelson P. and A. J. Klassen. Mennonite bibliography, 1631-1961. Scottdale: Herald Press, 1977, index under Devotional Literature, Family Prayer.

Toews, Abraham P. American Mennonite Worship: its Roots, Development and Application. New York: Exposition Press, 1960.

"The Voluntary Prayer Link," sent out by L. J. Burkholder, Markham, Ont., Nov. 1935-Oct 1940.

Wiebe, Katie Funk. Who are the Mennonite Brethren. Winnipeg and Hillsboro: Kindred Press 1984: 14-15.

Yoder, Paul M., et al, Four Hundred Years with the Ausbund. Scottdale, 1964.

| Author(s) | Thelma Miller Groff |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1989 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Groff, Thelma Miller. "Worship, Private." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1989. Web. 19 Jan 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Worship,_Private&oldid=173819.

APA style

Groff, Thelma Miller. (1989). Worship, Private. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 19 January 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Worship,_Private&oldid=173819.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 5, pp. 943-945. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.