Difference between revisions of "Ordinances"

| [unchecked revision] | [unchecked revision] |

GameoAdmin (talk | contribs) (CSV import - 20130820) |

GameoAdmin (talk | contribs) (CSV import - 20130823) |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

But J. C. Wenger's <em>Introduction to Theology</em> (1954), a widely accepted and influential book, returned to the concept of only two full ordinances, baptism and communion. -- CK | But J. C. Wenger's <em>Introduction to Theology</em> (1954), a widely accepted and influential book, returned to the concept of only two full ordinances, baptism and communion. -- CK | ||

| − | <h3>1989 Article</h3> From the time of Jesus onward the church has used outward and visible actions to represent inward, invisible power at work. Jesus anointed a man's eyes with clay to restore his sight (John 9:6 ff). In the early church [[Anointing with Oil|anointing with oil]] was a way of claiming the blessing of God for a sick person (James 5:14 ff.). By the 12th century the long evolution of Christian sacramental life in the western church was formalized when definitive rituals were specified by which saving grace was given. They were: [[Communion|communion]] (Eucharist, Lord's Supper), [[Baptism|baptism]], [[Confirmation|confirmation]], [[Marriage|marriage]], [[Ordination|ordination]], penance (discipline), and [[Anointing with Oil|anointing with oil]]. In these sacraments the grace which was signified was also effected in the person. For example, the bread of the Lord's Supper represented the body of Christ but, through the mediatorial role of the priest, it also became the body of Christ. | + | <h3>1989 Article</h3> From the time of Jesus onward the church has used outward and visible actions to represent inward, invisible power at work. Jesus anointed a man's eyes with clay to restore his sight (John 9:6 ff). In the early church [[Anointing with Oil|anointing with oil]] was a way of claiming the blessing of God for a sick person (James 5:14 ff.). By the 12th century the long evolution of Christian sacramental life in the western church was formalized when definitive rituals were specified by which saving grace was given. They were: [[Communion|communion]] (Eucharist, Lord's Supper), [[Baptism|baptism]], [[Confirmation|confirmation]], [[Marriage| marriage]], [[Ordination|ordination]], penance (discipline), and [[Anointing with Oil|anointing with oil]]. In these sacraments the grace which was signified was also effected in the person. For example, the bread of the Lord's Supper represented the body of Christ but, through the mediatorial role of the priest, it also became the body of Christ. |

To the Protestant reformers of the 16th century the medieval preoccupation with priestly and sacramental power obscured the personal access each believer has to the grace of God through faith in Christ. The Reformation rejected the necessity of the mediation of salvation by a priest and by the definitive seven sacraments. The principle of <em>sola Scriptura</em> (by Scripture alone) led Protestants to retain as sacraments only communion and [[Baptism|baptism]], claiming that Jesus had ordained only these two (Matthew 26:26 ff. and parallels, Matthew 28:19). At the same time individual reformers included, for example, preaching and love of neighbor ([[Luther, Martin (1483-1546)|Luther]]) and [[Discipline, Church|church discipline]] ([[Calvin, John (1509-1564)|Calvin]]) as marks of the church. | To the Protestant reformers of the 16th century the medieval preoccupation with priestly and sacramental power obscured the personal access each believer has to the grace of God through faith in Christ. The Reformation rejected the necessity of the mediation of salvation by a priest and by the definitive seven sacraments. The principle of <em>sola Scriptura</em> (by Scripture alone) led Protestants to retain as sacraments only communion and [[Baptism|baptism]], claiming that Jesus had ordained only these two (Matthew 26:26 ff. and parallels, Matthew 28:19). At the same time individual reformers included, for example, preaching and love of neighbor ([[Luther, Martin (1483-1546)|Luther]]) and [[Discipline, Church|church discipline]] ([[Calvin, John (1509-1564)|Calvin]]) as marks of the church. | ||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

Those [[Anabaptism|Anabaptists]] who retained the term "sacrament" to describe the Lord's Supper and baptism or other marks of the church generally redefined it because of negative associations carried by the term. [[Marpeck, Pilgram (d. 1556)|Pilgram Marpeck]] was typical. He resorted to the term's ancient meaning as an oath of loyalty, thereby shifting the emphasis from exclusive preoccupation with the divine to focus also on the human action (<em>CRR</em> 2:169-72). By means of the function of co-witness, Marpeck described a sacrament as a dynamic event in which bread and wine or water testify to the person of faith that Christ is savingly present (<em>CRR</em> 2:88; Marpeck, <em>Vermanung in Gedenkschrift</em>, ed. C. F. Neff [1925], 207; Marpeck <em>Verantwortung in Marbeck-Schwenkfeld</em>, ed. J. Loserth [1929], 109). At the same time, Marpeck showed a strong preference for the term "ceremony" which he defined as any external ritual given by Christ to proclaim the Gospel (<em>CRR</em> 2:44). His list of ceremonies included not only baptism and the Lord's Supper but feetwashing, preaching, the [[Ban|ban]], and acts of neighbor love. While not including [[Dedication of Infants|infant dedication]] in this list, he did provide a theological rationale for its practice (<em>CRR</em> 2:140, 147, 242, 247). | Those [[Anabaptism|Anabaptists]] who retained the term "sacrament" to describe the Lord's Supper and baptism or other marks of the church generally redefined it because of negative associations carried by the term. [[Marpeck, Pilgram (d. 1556)|Pilgram Marpeck]] was typical. He resorted to the term's ancient meaning as an oath of loyalty, thereby shifting the emphasis from exclusive preoccupation with the divine to focus also on the human action (<em>CRR</em> 2:169-72). By means of the function of co-witness, Marpeck described a sacrament as a dynamic event in which bread and wine or water testify to the person of faith that Christ is savingly present (<em>CRR</em> 2:88; Marpeck, <em>Vermanung in Gedenkschrift</em>, ed. C. F. Neff [1925], 207; Marpeck <em>Verantwortung in Marbeck-Schwenkfeld</em>, ed. J. Loserth [1929], 109). At the same time, Marpeck showed a strong preference for the term "ceremony" which he defined as any external ritual given by Christ to proclaim the Gospel (<em>CRR</em> 2:44). His list of ceremonies included not only baptism and the Lord's Supper but feetwashing, preaching, the [[Ban|ban]], and acts of neighbor love. While not including [[Dedication of Infants|infant dedication]] in this list, he did provide a theological rationale for its practice (<em>CRR</em> 2:140, 147, 242, 247). | ||

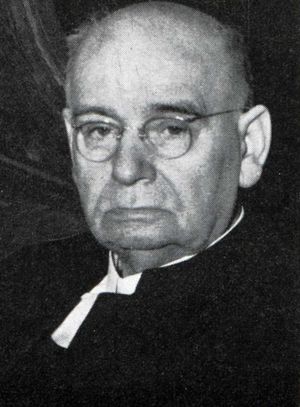

| − | [[File:ME2-16-1.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Balthasar | + | [[File:ME2-16-1.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Balthasar |

| − | Hubmaier | + | Hubmaier'']] [[Hubmaier, Balthasar (1480?-1528)|Balthasar Hubmaier]] and most Swiss Brethren shared Marpeck's preference for the term "ceremony," generally limiting its scope to baptism and the Lord's Supper. They understood ceremonies as human responses to previously received grace. This response, however, comes not only from the individual but also from the church. In the act of baptism for instance, the believer confesses faith in Christ; at the same time the church gathers the believer into the [[Community|community]]. In communion believers promise each other that they will love and discipline each other and suffer for Christ in the world (Hubmaier, <em>Schriften</em>, 346, 104, 317-18). |

| − | |||

| − | '']] [[Hubmaier, Balthasar (1480?-1528)|Balthasar Hubmaier]] and most Swiss Brethren shared Marpeck's preference for the term "ceremony," generally limiting its scope to baptism and the Lord's Supper. They understood ceremonies as human responses to previously received grace. This response, however, comes not only from the individual but also from the church. In the act of baptism for instance, the believer confesses faith in Christ; at the same time the church gathers the believer into the [[Community|community]]. In communion believers promise each other that they will love and discipline each other and suffer for Christ in the world (Hubmaier, <em>Schriften</em>, 346, 104, 317-18). | ||

In the Dutch-North German communities the marks of the church were most often called "ordinances," from the fact that Christ had ordained them. [[Dirk Philips (1504-1568)|Dirk Philips]] stipulates seven ordinances ([[Ordination|ordination]], sacraments, feetwashing, discipline, neighbor love, crossbearing, suffering) (Dirk <em>Enchiridion</em>, trans. A. Kolb, 383-400). The term "sacraments" in this list refers to communion and baptism; it is used to indicate their primacy in the life of the church. All the ordinances make the church's life of obedience visible. On the other hand, the two sacraments are signs of obedience but also of the grace which makes obedience possible. | In the Dutch-North German communities the marks of the church were most often called "ordinances," from the fact that Christ had ordained them. [[Dirk Philips (1504-1568)|Dirk Philips]] stipulates seven ordinances ([[Ordination|ordination]], sacraments, feetwashing, discipline, neighbor love, crossbearing, suffering) (Dirk <em>Enchiridion</em>, trans. A. Kolb, 383-400). The term "sacraments" in this list refers to communion and baptism; it is used to indicate their primacy in the life of the church. All the ordinances make the church's life of obedience visible. On the other hand, the two sacraments are signs of obedience but also of the grace which makes obedience possible. | ||

Revision as of 14:15, 23 August 2013

1959 Article

Ordinances is a term used in non-liturgical churches to designate what is referred to in liturgical churches as "sacraments." There is considerable difference in meaning between these two terms. A sacrament is defined by Thomas Aquinas as a "sign of a sacred thing in so far as it sanctifies man." Augustine referred to it as "the visible form of an invisible grace." "The sign" and the "visible form" became more and more significant and a prerequisite for the appropriation of the "invisible grace." The 16th-century Reformers broke with the medieval concept, although the term "sacrament" was retained in the liturgical Protestant churches; only two sacraments, baptism and the Lord's Supper, were retained. In the Anglican and Lutheran churches a reinterpreted Catholic tradition was retained, while the Reformed, Presbyterians, Anabaptists, and other churches altered the meaning completely, giving usually only a symbolic meaning.

None of the other non-liturgical churches of the Reformation broke as radically with the tradition as did the Anabaptists and Spiritualists. The latter were forerunners in a way of the Quakers, who spiritualized the ordinances completely. But the Biblical Anabaptists retained baptism and the Lord's Supper, and in Holland feetwashing, as ordinances of the Lord. The term "ordinance" emphasizes the aspect of institution by Christ and the symbolic meaning. For this reason the use of the term "sacraments" by Mennonites is misleading. Nevertheless, it is being used at times particularly by ministers who have received training in non-Mennonite institutions of liturgical leanings, and was also used at times by the early Anabaptists (see Sacraments).

Bernhard Rothmann in his Restitution stated that the Antichrist had through "his witchcraft" made an idol of baptism. Menno Simons agreed with this statement (Krahn: 131 ff.). Constantly he fought the concept of magical implications and power in baptism and emphasized that only an "inward baptism" can save. After the spiritual baptism of regeneration has taken place, water baptism as a sign of obedience follows. If salvation lay in the outward form, God would have made water, not the blood of Christ, necessary for forgiveness of sin. God has not elevated the elements of water, bread, and wine above other elements but uses them merely as symbols of His forgiving grace.

We use them to demonstrate our obedience and faith. Menno Simons warns, however, against the spiritualization of the ordinances to the point where they become obsolete as was the case among the Spiritualists, e.g., Sebastian Franck and to some extent Hans Denck. Since baptism and the Lord's Supper are symbolic and not absolute conveyors of God's grace, little significance is attached to their precise form. For the early Anabaptists the questions whether baptism should be administered by pouring, sprinkling, or immersion and whether in the Lord's Supper wine or unfermented juice should be used could never have led to controversy.

Dirk Philips spoke of the ordinances as witnesses of the love of God and the deeds of Jesus Christ. However, both he and Menno Simons were very cautious in avoiding the words "signs of grace" for the Lord's Supper and baptism, because they feared that outward forms would again take the place of the atoning death of Christ. The power of the ordinances is not in the sign or symbol but in what these two stand for (Hoekstra: 277).

In addition to the two generally accepted ordinances, most Dutch Anabaptists (not Swiss) and Mennonites, and the Amish as well as the Mennonite Church (MC) and related groups, have practiced and retained footwashing as another ordinance, performed either before or after the Lord's Supper. Menno did not emphasize the ordinance character of footwashing as strongly as that of baptism and the Lord's Supper; it was for him a symbol of unselfish love, hospitality toward the brethren, and humility.

Within the Mennonite churches of later centuries the forms of the ordinances gained in significance and at times obscured their deeper meaning. Controversies about the form of baptism arose because the outward sign had become more important than God's gift and its inward experience. (See also Baptism.)

In the Mennonite Church (MC) in the 20th century, largely through the influence of the writings of Daniel Kauffman, the idea of seven ordinances arose and became quite common, though not fixed in any confession of faith or conference disciplines. The seven were listed as baptism, communion, footwashing, prayer veiling for women, anointing with oil, the kiss of charity, and marriage.

But J. C. Wenger's Introduction to Theology (1954), a widely accepted and influential book, returned to the concept of only two full ordinances, baptism and communion. -- CK

1989 Article

From the time of Jesus onward the church has used outward and visible actions to represent inward, invisible power at work. Jesus anointed a man's eyes with clay to restore his sight (John 9:6 ff). In the early church anointing with oil was a way of claiming the blessing of God for a sick person (James 5:14 ff.). By the 12th century the long evolution of Christian sacramental life in the western church was formalized when definitive rituals were specified by which saving grace was given. They were: communion (Eucharist, Lord's Supper), baptism, confirmation, marriage, ordination, penance (discipline), and anointing with oil. In these sacraments the grace which was signified was also effected in the person. For example, the bread of the Lord's Supper represented the body of Christ but, through the mediatorial role of the priest, it also became the body of Christ.

To the Protestant reformers of the 16th century the medieval preoccupation with priestly and sacramental power obscured the personal access each believer has to the grace of God through faith in Christ. The Reformation rejected the necessity of the mediation of salvation by a priest and by the definitive seven sacraments. The principle of sola Scriptura (by Scripture alone) led Protestants to retain as sacraments only communion and baptism, claiming that Jesus had ordained only these two (Matthew 26:26 ff. and parallels, Matthew 28:19). At the same time individual reformers included, for example, preaching and love of neighbor (Luther) and church discipline (Calvin) as marks of the church.

Those Anabaptists who retained the term "sacrament" to describe the Lord's Supper and baptism or other marks of the church generally redefined it because of negative associations carried by the term. Pilgram Marpeck was typical. He resorted to the term's ancient meaning as an oath of loyalty, thereby shifting the emphasis from exclusive preoccupation with the divine to focus also on the human action (CRR 2:169-72). By means of the function of co-witness, Marpeck described a sacrament as a dynamic event in which bread and wine or water testify to the person of faith that Christ is savingly present (CRR 2:88; Marpeck, Vermanung in Gedenkschrift, ed. C. F. Neff [1925], 207; Marpeck Verantwortung in Marbeck-Schwenkfeld, ed. J. Loserth [1929], 109). At the same time, Marpeck showed a strong preference for the term "ceremony" which he defined as any external ritual given by Christ to proclaim the Gospel (CRR 2:44). His list of ceremonies included not only baptism and the Lord's Supper but feetwashing, preaching, the ban, and acts of neighbor love. While not including infant dedication in this list, he did provide a theological rationale for its practice (CRR 2:140, 147, 242, 247).

Balthasar Hubmaier and most Swiss Brethren shared Marpeck's preference for the term "ceremony," generally limiting its scope to baptism and the Lord's Supper. They understood ceremonies as human responses to previously received grace. This response, however, comes not only from the individual but also from the church. In the act of baptism for instance, the believer confesses faith in Christ; at the same time the church gathers the believer into the community. In communion believers promise each other that they will love and discipline each other and suffer for Christ in the world (Hubmaier, Schriften, 346, 104, 317-18).

In the Dutch-North German communities the marks of the church were most often called "ordinances," from the fact that Christ had ordained them. Dirk Philips stipulates seven ordinances (ordination, sacraments, feetwashing, discipline, neighbor love, crossbearing, suffering) (Dirk Enchiridion, trans. A. Kolb, 383-400). The term "sacraments" in this list refers to communion and baptism; it is used to indicate their primacy in the life of the church. All the ordinances make the church's life of obedience visible. On the other hand, the two sacraments are signs of obedience but also of the grace which makes obedience possible.

Even though Anabaptists were anti-clerical in the sense described above, most of them including Hubmaier (Schriften, 355ff) Dirk (Kolb, 67ff, 77ff.) and the Schleitheim Confession (art. V), emphasize the role of an ordained leader in presiding over those ordinances which are part of worship.

Without formally designating them as ordinances, the formative Mennonite confessions of faith all include marriage, ordination, feetwashing, discipline, and neighbor love (often under the category of nonresistance) as essential signs of how God orders the life of the church (Dordrecht in Loewen, Confessions, 66-69; Flemish-Frisian-High German, ibid., 117-27/115-25; Ris, ibid., 96-102/94-100). The Mennonite Brethren (MB) confession of 1902 adds preaching to baptism and the Lord's Supper as means of grace" (Loewen, Confessions, 166).

Though they are not listed in confessional or worship documents prior to the 1890s, oral tradition in some Mennonite circles has preserved the practices of infant dedication and anointing of the sick. The Gnadenfeld rite of the main Mennonite group in Russia ("Kirchen-Gemeinden") includes an infant dedication service clearly adapted from the ritual of infant baptism, no doubt because the Gnadenfeld congregation was originally Lutheran (Handbuch für Prediger, 64-65). Although other marks of the church have receded in use, infant dedication has become an almost universal practice among the main Mennonite conferences in North America. The greater attention to children as people in their own right has contributed to the desire of parents to have their children included in the care of God and of the church by means of a specific event. Attention has been given to make the difference between infant presentation and baptism clear (e.g., Minister's Manual, [Evangelical Mennonite Conference], 52). In some circles, however, infant dedication is increasingly seen as the inclusion of children in all aspects of the church's life. This has both stemmed from and led to less emphasis on conversion, catechism, and baptism as the necessary prerequisites for full participation in the life of the church.

The renewal of extraordinary healing as practiced in the charismatic movement has encouraged the more regular use of the practice of anointing the sick. The 1983 Mennonite Church (MC)-General Conference Mennonite Church (GCM) minister's manual includes a healing service (Janzen and Janzen, Minister's manual, 106-10).

Only two Mennonite confessions speak to the question of celibacy; the Ris and the 1930 General Conference Mennonite statements give it the same status as marriage (Loewen, Confessions, 102, 307). Among the Mennonites in Russia the celibate life was given structure in the form of communities of sisters, most of whom became nurses. The last of these to survive are the deaconesses who managed a hospital in Newton, Kansas, until the early 1980s.

About 1900 Daniel Kauffman tried to counter the assimilation of his community into its North American environment by developing a strong and specific teaching on ordinances (Bible doctrines (1914), pt. VI, pp. 353-458). He sought not only to strengthen doctrine and practice concerning baptism, communion, feetwashing, anointing, and marriage, but to elevate the kiss of peace and the devotional covering or prayer veil to the status of ordinances. Both of the latter originate in the New Testament (2 Corinthians 13:12; 1 Corinthians 11:2ff.) and have been practiced throughout the centuries but have never been seen as fundamental marks of the church.

Kauffman's goal was to use these outward signs to distinguish visibly the life-style of the Mennonite Church (MC) from that of the world around it. His understanding one-sidedly emphasized ordinances as tests of obedience to church teaching so that no room was left for them also to be evidences of grace. Kauffman's list of ordinances was never given formal sanction in a confession of faith except for the 1952 Statement of Doctrine of the Church of God in Christ Mennonite (Holdeman) (Loewen, Confessions, 205).

Mennonites universally celebrate baptism and communion as essential marks of the church, and as Marpeck said, as ways of proclaiming the Gospel. The term sacrament is often used as Dirk used it, to describe the primacy of these two rituals above the other ceremonies of the church. But an unwritten theology has developed around the other traditional ordinances as well. Preaching is commonly understood as the decisive event in the life of the church in which the word of God comes to life. The wedding service is widely perceived as the event in which God makes a marriage out of two people's love. Except in very liberal circles, the act of ordination is thought of as the setting aside of a minister for life-long service. Where ministers are chosen by casting lots, it is believed that God's choice is revealed through a process culminating in the selecting of a book. In many congregations, especially those with membership from a predominantly Pennsylvania-German background, feetwashing is practiced in conjunction with the Lord's Supper. In the smaller, conservative bodies excommunication and readmission to the church come about through ritual public acts believed to embody the will and grace of God.

There has never been complete clarity in the Mennonite mind as to what status and meaning to give to the various ceremonies by which the church expresses its life. A surprising variation exists not only in the number of ordinances practiced, but in their form. For example, immersion, sprinkling, and pouring have all been practiced as modes of baptism since the 16th century. The liturgical ordering of all church rituals has varied since the beginning but even more since the movement of worship renewal and experimentation which began in the 1960s. Oral tradition and minister's manuals are considered as guides rather than rules of observance.

Historically, as Mennonites have acculturated into their religious and cultural surroundings, the status and number of their ordinances has diminished. The extreme of this tendency took place in 19th century Holland. By then feetwashing and church discipline had vanished. But for a short time several urban congregations did away even with baptism and communion! Recent Mennonite teaching, as evidenced by instruction in theology schools and texts (e.g., Kaufman, Finger, the Worship series published jointly by the Mennonite Church and General Conference Mennonites) concentrates almost exclusively on baptism and communion as marks of the church.

By way of brief theological commentary on the development of Mennonite teaching on ordinances the following may be said. There has been an enduring ambivalence concerning the role of ceremonies in the life of the church. With other Protestants Mennonites have taught that each believer has unmediated access to the grace of God through faith in Christ. Because of their conviction that salvation is given through an existential relationship with Christ, Mennonites believe that baptism may be offered to believers only. At the same time they have claimed that the church is the bearer of grace. It is through the church's mediation of the gospel across time that the individual comes to faith and is sustained in faith. That is, each person comes to Christ through the witness of the church and, upon confession of faith, is baptized and brought into its community. One might say that in Mennonite theology the church itself is the sacrament of Christ's presence. Its individual ceremonies particularize both his grace and the believers' faith.

Several factors have complicated this double conviction about the church's mediation of grace and the unmediated access of each believer to grace. From the beginning theologians have found it difficult to describe how this reality is present in individual ordinances. Marpeck was the only Anabaptist who worked out a systematic position. Dirk's writings mirror the ambivalence of his community. Hubmaier's resolution was radical but also one-sided. He described a ceremony as only a response to grace rather than also a means of grace. The Spirit, without external mediation, was the means of grace. But the response to grace was both an individual and communal act. For example in baptism, the individual externalized her faith. At the same time, by baptizing someone and bringing him into its community the church confirmed the individual's faith. Hubmaier and, to a lesser extent, Dirk represent the dominant historic Mennonite interpretations of ordinances.

In time, especially with the rise of individualism, the role of the church receded. Baptism, communion, and other marks of the church were increasingly understood as individual acts of confession, thanksgiving, etc. Gradually, what was believed concerning baptism was carried over to what was believed concerning salvation: it was a humanly willed decision to live as Christ had commanded. Correctives to this overly simplified view went in two directions. One was the pietistic or revivalistic emphasis on an individual relationship with Christ in which the church and sacraments had no essential role. The other was the objective use of ceremonies, as illustrated by the example of baptism, to bring people into the church without a response of personal faith. This was the tendency of Mennonites of North German background in the 19th century and led to protests, one of which resulted in the formation of the Mennonite Brethren Church (MB) in Russia. Daniel Kauffman's attempt at a renewal of the ordinances, on the other hand, challenged individualism and reemphasized the church but made ceremonies signs of ethical achievement, further separating them from the work of grace.

Revivalistic individualism, mechanical sacramentalism, and ceremonies as signs of nonconformity all continue to be practices in the Mennonite churches and to remove them from the Anabaptist "double conviction" about the inseparability of the individual's and church's role in salvation. At the same time, the recovery of the Anabaptist vision in the past generation has led to a strengthened theology of the church. The implications of this ecclesiology for sacraments has not yet been widely realized. In large part this is a result of a lack of attention to Christology throughout most of Mennonite history. That is, if Christ is present in the church today his presence must be taken into account in practicing the ordinances, which whatever else they be, are signs of his work in the church. The recent systematic theologies of Gordon Kaufman and Thomas Finger work toward a broader theology of baptism and communion, though without an anchor in Mennonite tradition. The popular clamor for a fuller theology and practice of worship, exemplified in a festival of worship held at Goshen, Ind., in 1986, has led to considering sacramental life as part of its search.

In 1982 the World Council of Churches issued the fruit of 50 years of ecumenical debate and research under the title, Baptism, Eucharist and Ministry. It attempted to move beyond the traditional Orthodox, Catholic, and Protestant formulations. Responses to this statement from Believers Church perspectives, including Mennonite views, were published in 1986 (Strege, ed.).

No one has shown concern to rehabilitate neighbor love or suffering as ordinances, i.e., as concrete events in which Christ is present and in which the church takes form. To do so might strengthen their place in the life and mission of the church, demonstrate the inseparability of grace and faith, and show how ethically relevant it really is to concern ourselves with the ceremonies Christ left us. -- JDR

(See Communion, Baptism, Feetwashing, Prayer Veiling, Kiss, Holy, Anointing, and Sacraments.)

Bibliography

Armour, Rollin S. Anabaptist Baptism. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1966.

Baptism, Eucharist, and Ministry, Faith and Order Paper no. 111. Geneva: World Council of Churches, 1982.

Barth, Karl. Church Dogmatics vol. 4, Fragment 1, Baptism. Edinburgh: T and T. Clark, 1969.

Beachy, Alvin. The Concept of Grace in the Radical Reformation. Neiuwkoop: B. de Graf, 1977.

Beachy, Alvin. Worship as Incarnation. Newton, KS, 1966.

Clarke, N. A Theology of Sacraments. London: SCM, 1960.

Cronk, Sandra. "Gelassenheit: the Rites of the Redemptive Process in the Old Order Amish and Old Order Mennonite Communities." PhD diss., U. of Chicago, 1977, cf. Mennonite Quarterly Review, 65 (1981): 5-44.

Eller, Vernard. In Place of Sacraments. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1972.

Finger, Thomas N.. Christian Theology: an Eschatological Approach. Nashville : Thomas Nelson, 1985-

Goertz, Hans-Jürgen. Die Täufer. Munich: C. H. Beek, 1980.

Goltermann, W. "Eens Consens over de doop," in De Geest in het Geding. N.p: H. D. Tjeenck Willink, 1978.

Handbuch für Prediger. Berdyansk: n.p., 1911.

Hoekstra, S. Bz, Beginselen en leer der oude Doopsgezinden. Amsterdam, 1863: 276.

Hubmaier, Balthasar. Schriften. ed. G. Weston, T. Bergsten. Gütersloh: Gerd Mohn, 1962.

Janzen, Heinz and Dorothea, eds., Ministers Manual. Newton, KS: Faith and Life, 1983.

Kauffman, Daniel, ed. Doctrines of the Bible. 2nd ed. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1929.

Kauffman, Daniel, ed. Mennonite Cyclopedic Dictionary. Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House, 1937.

Kaufman, Gordon. Systematic Theology: a Historicist Perspective. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1968.

Klaassen, Walter. Biblical and Theological Basis for Worship in the Believers' Church. Worship Series no. 1. Newton, KS, 1978, cf. related titles in this series.

Klassen, William and Walter Klaassen, eds. The Writings of Pilgram Marpeck, Classics of the Radical Reformation, vol. 2. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1978.

Krahn, Cornelius. Menno Simons (1494-1561). Karlsruhe, 1936: 129.

Loewen, Howard John, ed. One Lord, One Church, One Hope, One God: Mennonite Confessions of Faith. Text-Reader series. Elkhart, IN: Institute of Mennonite Studies, 1985.

Marpeck, Pilgram. Vermanung in Gedenkschrift. ed. C. F. Neff. 1925.

Marpeck, Pilgram. Verantwortung in Marbeck-Schwenkfeld. ed. J. Loserth. 1929.

Martin, D. D. "Menno and Augustine on the Body of Christ." Fides et Historia 20, no. 3 (Fall 1988): 41-64.

Martos, J. The Catholic Sacraments. Wilmington: Michael Glazier, 1983.

Mast, Russell. Preach the Word. Newton, KS, 1968.

Ministers Manual. Steinbach, MB: Evangelical Mennonite Conference, 1983.

Rempel, John D. "Christology and the Lord's Supper in Anabaptism: a Study in the Theology of Balthasar Hubmaier, Pilgram Marpeck, and Dirk Philips." ThD diss., St. Michael's College, Toronto School of Theology, U. of Toronto, 1986.

Rempel, John D. "Christian Worship: Surely the Lord is in This Place." Conrad Grebel Review 6 (1988): 101-17.

Rues, S. F. Aufrichtige Nachrichten von dem gegenwärtigen Zustande der Mennoniten. Jena, 1743: 50.

Strege, Merle D., ed. Baptism and Church, from the 7th Believers Church Conference, 1984. Grand Rapids: Sagamore Books, 1986.

Windhorst, Christoph. Täuferisches Taufverständnis. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1976.

Van der Zijpp, Nanne. Geschiedenis der Doopsgezinden in Nederland. Arnhem, 1952: 115.

Yoder, John Howard. Täufertum und Reformation im Gespräch. Zürich: EVZ Verlag, 1968.

Additional Information

Seven Articles of Schleitheim (Anabaptist, 1527)

Dordrecht Confession of Faith (Mennonite, 1632)

Mennonite Articles of Faith (Mennonite (Cornelis Ris), 1766)

Confession of Faith (Mennonite Brethren Church, 1902)

| Author(s) | Cornelius Krahn |

|---|---|

| John D. Rempel | |

| Date Published | 1989 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Krahn, Cornelius and John D. Rempel. "Ordinances." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1989. Web. 16 Apr 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Ordinances&oldid=93202.

APA style

Krahn, Cornelius and John D. Rempel. (1989). Ordinances. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 16 April 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Ordinances&oldid=93202.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 4, pp. 72-73, v. 5, pp. 658-660. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.